|

As a rule, vegetables are

more difficult to can successfully than are fruits. However, if the

fundamental principles involved are well understood, good results may be

uniformly. obtained in canning all vegetables with ordinary kitchen

equipment. The difficulties of vegetable canning and methods of

overcoming these difficulties are taken up in the following paragraphs.

A great deal of interest

has been taken recently in vegetable canning, because of cases of fatal

poisoning from the use of home canned vegetables. These poisonings have

been caused by a very powerful toxin produced in jars or cans of

improperly sterilized vegetables by the growth of an organism known as

Bacillus botulinus. Experiments and experience have shown, however, that

the methods described in this book are perfectly safe. All that is

necessary is that the methods be well understood and applied

intelligently.

16. Peeling and

Preparing. Vegetables for canning should be as fresh as possible.

Waste no time in getting the vegetable from the garden into the can.

Asparagus becomes tough and bitter if held twenty-four hours. String

beans lose flavor and crispness; peas may ferment; and corn loses in

flavor and sweetness if kept too long uncanned after gathering. The

vegetables should therefore be canned on the same day that they are

picked.

Vegetables should usually

be graded for size and appearance. The amount of grading will depend on

whether the product is for home use or for sale. Grade asparagus into

two or three sizes and peas into young tender pods and larger, more

mature pods. Other vegetables need not be graded, unless for sale. In

this case select the material of best appearance for canning for market

and the less attractive vegetables for home use.

The vegetables should be

thoroughly washed to remove earth, etc. A large tub may be used for

this.

In small scale canning

the peeling, cutting, and preparation for the can must in practically

all cases be done by hand. Root vegetables such as beets, turnips, and

carrots, may be peeled by the peeler shown in figure 43. In canning

factories, peas are threshed and graded by machinery, while corn is

silked and cut from the cob by special machines. Other vegetables are

prepared largely by hand labor.

17. Blanching or

Parboiling. Most vegetables are given a short preliminary boiling in

water after grading, cutting, and peeling. This improves the texture and

color and usually removes disagreeable flavors and mucilaginous

substances from the skins. The process is spoken of as "blanching," but

is nothing more nor less than parboiling.

The prepared vegetables

are placed in a screen basket or in a cheesecloth and plunged into

vigorously boiling water for a length of time varying from a few seconds

to ten minutes, the time depending on the vegetable and its degree of

maturity. Small green peas will require less than a minute, while large

stalks of asparagus may require ten minutes' blanching. Blanching cooks

the vegetables more rapidly than cooking in the can, and tough

vegetables can be made tender with less trouble in the blanching process

than in the sterilization process. Convenient methods of blanching are

illustrated in Fig. 8. Tomatoes are parboiled or steamed about one

minute and beets about fifteen minutes to cause the skins to slip off

easily in peeling. They are chilled after heating to facilitate handling

in peeling.

18. Chilling. The

blanched vegetables must be placed in the can with all expediency. To

make them cool enough to handle, they should be plunged into cold water

after blanching. Chilling in this way also sets the color in green

vegetables and tends to make most vegetables more crisp.

19. Brine and

Acidified Brines. Vegetables, with the exception of tomatoes, are

canned in dilute brine. Tomatoes are canned without any liquid except

their own juice.

The usual brine contains

from two to three ounces of salt per gallon. For practical purposes, an

ounce is equivalent to a level tablespoonful of salt; this rule will

save trouble in making up small quantities of brine.

Most vegetables are

deficient in acid and if canned in a salt brine only are very difficult

to sterilize. That is to say, the spores of the bacteria occurring on

vegetables are very difficult to kill under this condition. If, however,

the deficiency in acidity of the vegetables is made up by the addition

of a small amount of some harmless acid substance such as lemon juice or

vinegar, the vegetables are as easily sterilized as fruits. For example,

in ordinary brine, asparagus must be sterilized for at least three hours

in boiling water, while if a small amount (4 ounces or 8 tablespoonfuls

per gallon) of lemon juice is added, this vegetable may be sterilized in

one hour or less. Other vegetables behave similarly. Vinegar may be used

to replace lemon juice, although slightly 'more is needed because

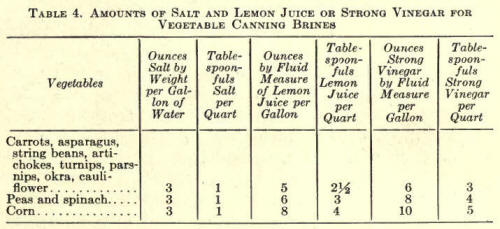

ordinary vinegar is not quite so acid as lemon juice. The following

table gives the amounts of salt and lemon juice or cider vinegar to use

for various vegetables.

The advantage of this

so-called "lemon juice" method is that the time of sterilization in

water at 212° is greatly shortened and made much more certain. It is

probably the most satisfactory method for home canning. The amount used

does not materially affect the flavor. The brine can be discarded when

cans are opened and the vegetables cooked in fresh liquid or a small

amount of baking soda may be added.. This will remove practically all

taste of the lemon juice or vinegar, should this flavor prove

objectionable. Many vegetables are improved by the addition of the small

amount of lemon juice or vinegar recommended.

20. Addition of the

Brine. The brine should be added boiling hot to cans that are to be

sealed, or the cans should be exhausted in steam or boiling water before

sealing (see paragraph 14). Jars require a shorter time to heat if

filled with hot brine. A teapot makes a very convenient utensil for

heating and pouring brines or sirups into cans or jars. (See Fig. 10.)

21. Sterilization.

Four ways of sterilizing vegetables are used. These are: (a)

Sterilization under steam pressure; (b) intermittent sterilization in

boiling water; (c) sterilization in boiling water by a single long

sterilization; and (d) sterilization in boiling water by a relatively

short heating after addition of a small amount of lemon juice or vinegar

to the brine used in canning.

(a) Pressure

Sterilization: The boiling point of water rises if steam is confined in

a closed space, and temperatures much above 212° F. can be attained in

this way. By this means the spores of many bacteria that are killed with

the greatest difficulty at the temperature of boiling water are

destroyed by a few minutes' heating under five to fifteen pounds' steam

pressure. These pressures correspond to 228° F. and 250° F.,

respectively.

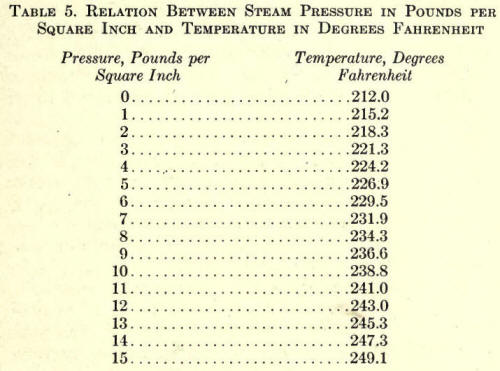

The following table shows

the relation between steam pressure in pounds per square inch and

temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. The table is of use where the

sterilizer used may not be equipped both with a thermometer and a steam

gauge.

The steam pressure

sterilizer is independent of altitude and therefore is of value in

elevated regions.

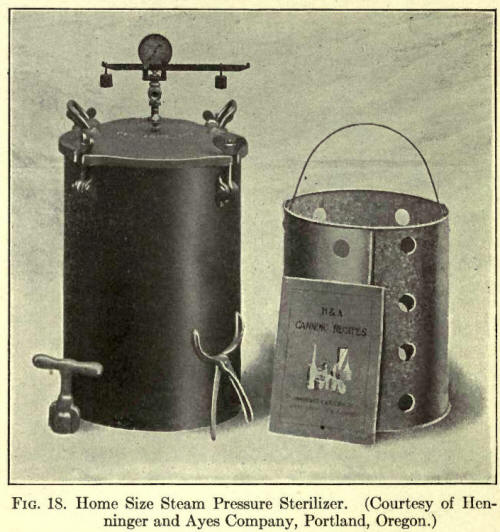

Several forms of steam

pressure sterilizers for home use are on the market. There is one known

as the "water seal outfit," which gives temperatures only slightly above

the boiling point of water. This is considered favorably by many home

canners; because it requires only a small amount of water, is easily

heated, and is inexpensive. Another type can be operated only up to five

pounds' pressure per square inch. Most forms of pressure cookers will

withstand a steam pressure of 15 pounds or more per square inch.

Steam pressure

sterilizers or retorts can be obtained in sizes holding from two dozen

cans to several thousand. The small outfits are heated by direct heat;

the large ones, by steam from a boiler.

Steam pressure

sterilizers can be used for sterilization at 212° F. by simply opening

the release cock and keeping the pressure at 0 pounds.

Steam pressure

sterilizers are well suited to sterilization of cans but are not

convenient for jars.

In using the sterilizer,

seal the cans of vegetables hot and place them in the basket or crate.

Add water to the depth of several inches. Lower the crate and contents

into the retort. Clamp the lid securely on the sterilizer and leave the

release cock open. Heat the water to boiling and as soon as steam

escapes freely from the cock close it. The purpose of leaving the cock

open at first is to allow the steam to displace the air in the retort;

otherwise the pressure in the retort would be due to compressed air and

the temperature would be uneven and not in proportion to the indicated

temperature or pressure. Heat until the dial of the steam gauge

indicates the desired pressure or until the thermometer reaches the

desired temperature for the required length of time by regulating the

fire or by opening the release cock sufficiently, and by setting the

weight on the safety valve so that it will release the steam

automatically when the proper pressure is reached.

When the cans have been

sterilized sufficiently, open the release cock and as soon as the

pressure falls to zero, remove crate and contents and cool in a tub of

cold water if cans have been used.

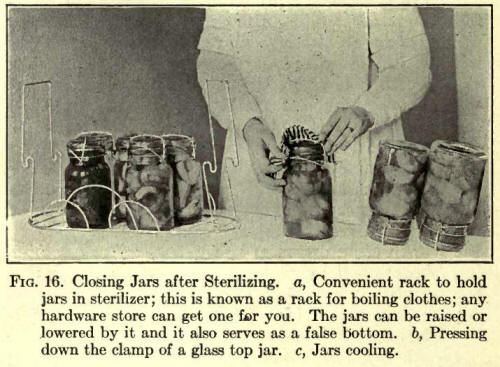

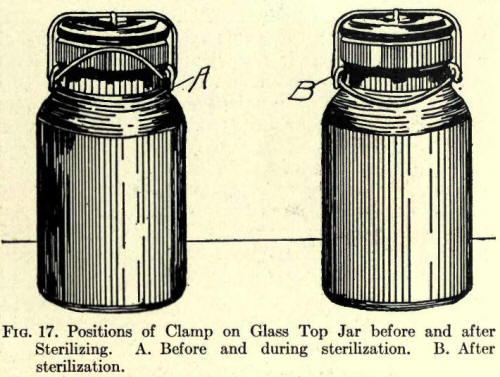

If jars are used, leave

the lids and rubbers on loosely during sterilization. Close immediately

after removal from the sterilizer, but do not, of course, chill the

jars. (See Fig. 18.)

(b) Intermittent or

Three-Day Sterilization of Vegetables at 212° F. is accomplished by

heating the container and contents to the boiling point of water for a

specified length of time on several (usually three), consecutive days.

It is the most effective method at 212° F., because the bacterial spores

start to grow between sterilizations from the softening effect of the

heat and are easily killed by the second and third sterilizations.

Cans are sealed hot and

heated usually for one hour in boiling water or steam on each of three

successive days. Jars are heated the first day with rubbers removed and

caps on jars loosely. At the end of the first sterilization rubbers are

sterilized in boiling water about five minutes, placed on the hot jars

and the caps are screwed down. The second and third days the

sterilizations are carried out without loosening the caps because the

vacuum formed after the first day's sterilization will prevent bursting

of the jars.

The three-day method is

safe, but often softens the vegetables so much that they become

unattractive in appearance.

(c) Sterilization of

Vegetables at 212° F. by One-Period Method: By this method the

vegetables are heated in boiling water or steam once only, but for a

long period of time. The method is recommended strongly by the United

States Department of Agriculture in Farmers' Bulletin 839 and is in

extensive use.

No pressure sterilizer is used with this method. It sometimes results in

softening of the vegetables from overcooking. Results of investigations

by Dr. Dickson of Stanford indicate that this method does not always

kill spores of certain bacteria. Method "(2)," described below, requires

a shorter time of sterilization and therefore results in a more

attractive product.

(d) Sterilization by the

Lemon Juice Method: If a small amount of harmless vegetable acid in the

form of lemon juice or vinegar is added, the brine vegetables are,

easily sterilized by a single sterilization at 212° F. The vegetables

are best acidified by adding the lemon juice or vinegar to the brine

used in filling the cans or jars. The amounts to use for various

vegetables will be found in Table 4. The method is used as follows:

Pack the vegetables in

the usual way. Add the hot brine which has been acidified. Seal the cans

and put rubbers and caps loosely on the jars. Sterilize in boiling water

or steam from three-quarters to two hours, depending upon the vegetable.

Remove cans and chill in water. Remove jars and seal.

This method does not

result in overcooking and retains the color and flavor more perfectly

than other methods. It produces a slight acid taste in some vegetables.

This can be removed before cooking for the table by drawing off the

brine and cooking in fresh water in the usual way or by adding a small

amount of baking soda before cooking for the table. The method has been

proven safe and free from danger of botulinus poisoning. |