|

Fruit canning is one of

the most important of the food preservation industries. It is no longer

a by-product industry, but is now a primary industry for which enormous

quantities of fruit are grown annually.

In addition to the fruit

canned commercially, many millions of cans and jars are put up each year

by housewives in the kitchen or by families who use small scale canning

outfits. It is for those engaged in canning for home use or in a small

way for local sale that the following discussion is intended, although

the principles involved will be of interest to commercial fruit canners.

The various steps in the

canning process have been taken up in the order in which they occur in

practice and each is discussed separately. For convenience of reference,

the various topics taken up have been numbered serially. The material in

this chapter is general and aims to give the principles of canning and

descriptions of apparatus used rather than specific directions or

recipes. Recipes will be found in Part III, Recipes 1-19, inclusive.

1. Picking. Fruits

for canning should be prime ripe; not over-ripe and soft, or too green.

An exception to this rule is the pear. Pears should be picked when full

size, but still green and should then be ripened in the box because tree

ripened pears lack flavor and are coarse in texture. Under-ripe apricots

remain astringent and tasteless regardless of the amount of cooking or

sugar used.

The fruit should be

handled carefully to prevent bruising. Berries and soft fruit should be

kept in shallow boxes until canned.

The fruit should be taken

to the canning room as soon as picked. In most fruits, there is a rapid

deterioration both in texture and flavor after picking.

2. Grading and Sorting.

The appearance of the canned fruit is greatly improved by sorting the

fruit according to appearance and grading for size. In home canning all

grading can be done by hand and at the operator's discretion. Where

large quantities of fruit are to be graded for size, the grading for

size is done by mechanical graders that can be adjusted to different

varieties of fruit.

In home or small scale

canning three grades will usually be sufficient: "Fancy," consisting of

the finest and largest fruit; "Standard," medium sized fruit, and this

grade may also include fruit that is more or less imperfect in

appearance but of good size; "Pie Fruit," soft, small, and badly

blemished fruit.

Grading is highly

desirable if the fruit is canned for sale.

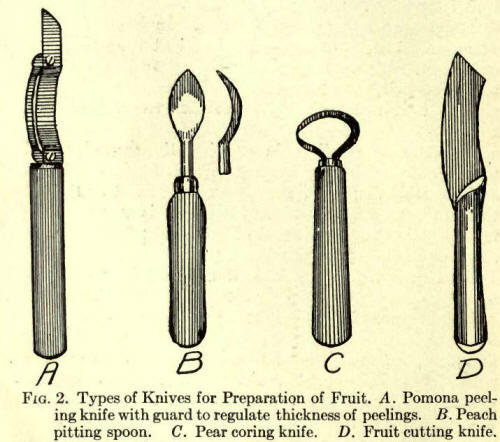

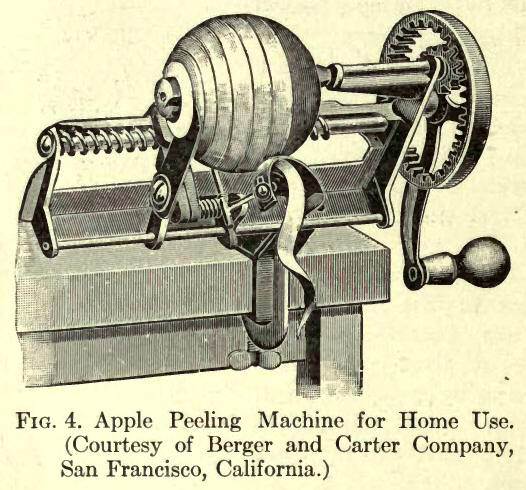

3. Peeling, Pitting,

Coring and Cutting. Large fruits for home canning are peeled,

usually by hand with a knife, although small hand power peelers for

apples and peaches are available. The Pomona and similar types of

peeling knives fitted with a guard will tend to prevent waste of fruit

in peeling (Fig. 2).

Peaches and apricots are

peeled commercially by immersing them in a boiling 10% solution of soda

lye. The method is rather difficult to use in the household. A

modification of this method of peeling can be used on a small scale as

follows: Make a solution of three-fourths of a pound of soda lye per

gallon of water. Use an agateware or iron pot; never aluminum. Heat to

boiling. Immerse the fruit in a wire basket in the hot lye long enough

(about 20 to 30 seconds), to soften the skin.

Plunge fruit into large

pot of cold water and rub off skins with the hands. Wash off all trace

of lye in another pot of water. Vigorous washing will be necessary to

remove the last traces of lye from the fruit.

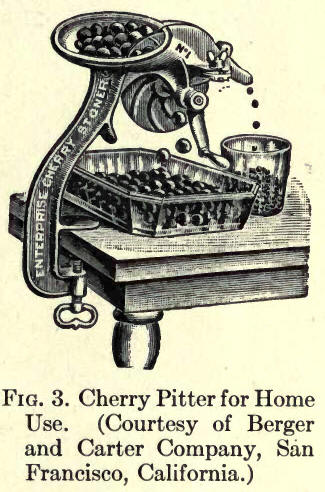

Cherries are often

pitted. Small hand pitters can be bought at any good hardware store for

fifty cents to a dollar. These same pitters can also be used for olives.

The pitters consist of a small plunger with a cross-shaped point that

forces out the pit.

A convenient cutting

knife for halving peaches, pears, etc., is shown in the accompanying

figure.

The pits of clingstone

peaches must be removed with a special pitting knife or "spoon." The

flesh is first cut along the line of suture with a cutting knife. The

pitting spoon is then forced into the peach at the stem end and is

manipulated so that the pit is cut from the flesh with as little loss as

possible of flesh adhering to the pit. The fruit is then cut in half and

is separated from the pit. Commercially, the halves are not peeled

before pitting and the peeling is done later in a lye vat; in the

household, it is advisable to peel cling peaches by hand before pitting.

Pears

are hand peeled; they are cut in half and the core removed with the

coring knife shown in Figure 2-C. Pears

are hand peeled; they are cut in half and the core removed with the

coring knife shown in Figure 2-C.

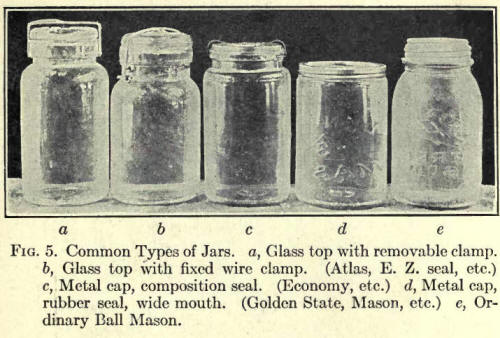

4. Jars. Because

they can be used repeatedly from year to year, jars are more

satisfactory than cans for putting up fruits in the household. There are

numerous types and sizes of glass jars. Most of these give satisfaction

if used properly. Their choice is largely a matter of personal

preference.

The various brands of

jars that are equipped with glass tops, rubbers, and wire clamps are

very satisfactory because of their durability, their simplicity, wide

openings for filling, convenience in sterilizing, and because of the

fact that no metal comes in contact with the food and it is not

necessary to replace the caps, as is often the case with some other

types of jars. The various modifications of the Economy jar are

excellent, if their use is well understood. They are sealed with a

lacquered metal cap carrying a composition which melts during

sterilization and hardens to form an air-tight seal as the jars cool.

The caps can be used only once.

The ordinary Ball Mason

jar is probably the most commonly used of all jars. The lacquered metal

caps are superior to the old style porcelain and zinc cap. This latter

style corrodes in time and becomes leaky. . The main objection to the

Mason jar is the narrowness of the jar mouth. A wide mouth Mason is now

on the market but the caps are very difficult to remove and must usually

be replaced each year. The new Mason with the so-called " vacuum seal "

is excellent.

More important than the

jar is the rubber. Select rubbers of the best material. Before buying,

test them, by stretching them severely. Brittle rubbers will not stand

processing; - they will often spread and cause leaks that result in

spoiling of the contents of the jar. Rubbers of good elasticity will

often last two seasons. It is, however, a good plan to buy new rubbers

each season rather than to risk spoiling through the use of old rubbers.

It is sometimes possible to use two old rubbers to each jar with good

results.

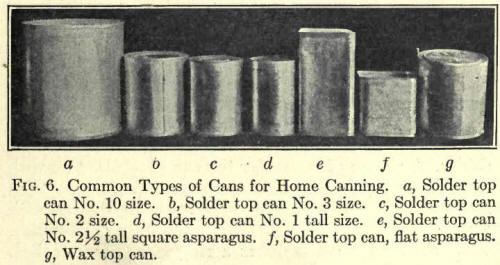

3. Wax Top Cans.

Three types of cans are used in home and farm canning. These are the wax

top can, the solder top can, and the open top or Sanitary can.

The wax top can is fitted

with a groove around the edge of the top. The lid fits into this and the

seal is made after sterilization by pouring hot sealing wax to fill the

groove or by filling the groove with a specially prepared waxed string.

The wax top cans are excellent for fruits but are not very satisfactory

for vegetables or meats, because of the difficulty in sealing the cans

while still boiling hot. It is possible to permit the cans to cool

slightly before sealing when used for fruit and then no difficulty is

met with in applying the wax. Advantages of the wax top can are its wide

opening through which large fruits and whole tomatoes may be filled into

the can and the fact that the cans may with care be used everal seasons.

The sealing is very simple and requires no special equipment or

experience.

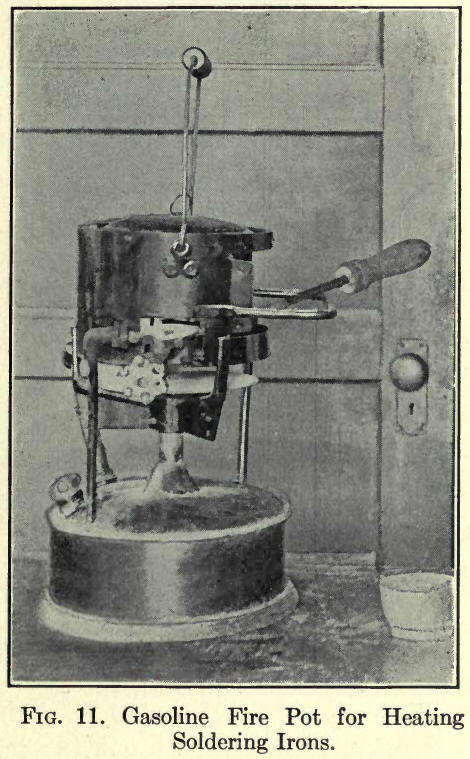

6. Solder Top Cans.

Solder top cans are closed with solder. The cap of the solder top can is

soldered on with a special soldering steel after the can is filled. It

is sealed by closing a small vent hole in the center of the can with a

drop of solder. Two styles of caps may be obtained. The solder hemmed

cap has a ring of solder attached. The lid is soldered to the can by

simply melting this ring of solder. The plain caps have no hem of solder

and solder must be melted against the capping steel. This is wasteful of

time and solder. Solder hemmed cap should be used if they can possibly

be procured. The sealing of solder top cans is described in a recipe and

illustrated in. Fig. 56.

7. Cooking the Fruit

before Filling the Containers, or Hot Pack Method. There are two

ways of canning fruits. These are known as the "cold pack " and the "hot

pack" methods, respectively. In the cold pack method the fruit is packed

into the jars or cans immediately after peeling, pitting, etc.; sirup or

water is added and the fruit is cooked in the container. The fruit holds

its shape and flavor well in this method but some fruits contract a

great deal during sterilization, leaving the jar or can unfilled. In the

hot pack method this contraction takes place outside the container and

more fruit can be packed into each can or jar. It is therefore a more

economical method for home use.

The fruit is prepared for

the can by grading, peeling, coring, and pitting as the case requires.

For sour fruits, one-half cup of sugar is added to each cup of fruit;

for sweet fruits one-fourth cup; for pie fruit, no sugar. Just enough

water is added to prevent scorching. The fruit is cooked over a slow

fire with very little stirring until about half cooked.

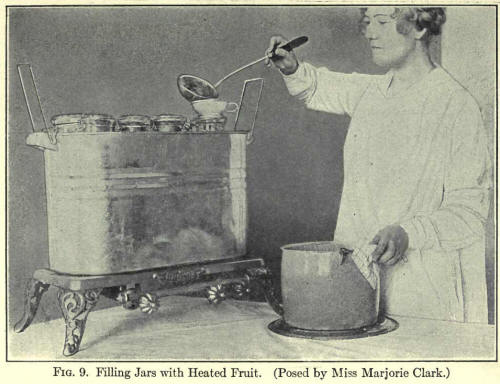

By means of a ladle and

wide mouthed funnel it is poured into scalded jars or cans and

sterilized.

This method differs from

the usual household "hot pack" method in which the fruit is completely

cooked before placing it in the jars and in which no further cooking is

given. The method of cooking completely before packing into cans or jars

results in considerable breaking of the fruit and gives a less

attractive appearing product.

8. Filling Jars and

Cans without Previous Cooking of the Fruit—Cold Pack Method. The

fruit is prepared by peeling, coring, and pitting. It is packed into

jars or cans without cooking. Hot sirup or water is added according to

the grade of fruit. Sterilization and cooking are carried out in the

cans or jars. This method is used exclusively by commercial canneries

and is recommended strongly by the United States Department of

Agriculture and the State Experiment Stations for use in the household.

It is the least laborious of any method, but is not best for household

use, because it does not utilize all of the space in the jars or cans,

because considerable shrinkage occurs during sterilization. Partial

cooking of the fruit

before canning and sterilizing gives better results in the kitchen.

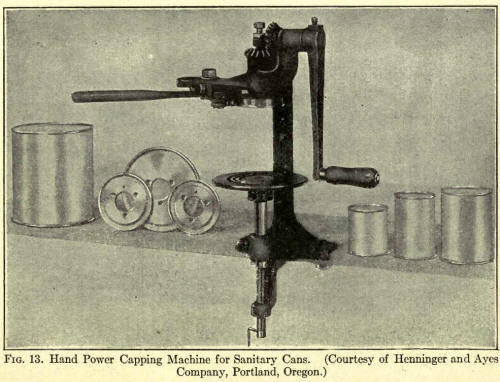

9. Sanitary Cans.

This is the type of can used in commercial canneries. No solder is used

in sealing it. The cap is crimped or spun on by a special machine after

the cans are filled.

The commercial sanitary

capping machine costs several hundred dollars or is rented by can

companies for about fifty dollars per season. A motor or other

mechanical source of power is necessary to run the capping machine.

Small hand power capping

machines costing from $13 and upward are available. Considerable skill

and experience are required to make their use a success. With care and

practice, however, satisfactory results can be attained. Directions for

the use of these machines accompany them. One form of hand power

sanitary can capping machine is shown in Fig. 13.

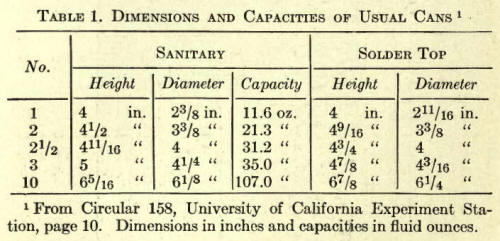

10. Sizes of Cans.

Cans for food preservation vary in size from about one-fourth of a pint

to five gallons. The sizes are usually designated by numbers rather than

by "quarts," "pints," or "gallons." The contents of solder top cans and

sanitary cans of the same numbers do not exactly correspond. The

following table gives the contents of the various sizes of sanitary and

solder top cans:

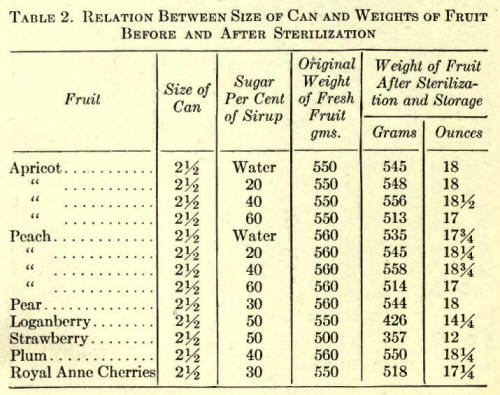

11. Net Weights that

Cans for Market Must Contain. Cans or jars of fruit for market are

packed according to weight. The net contents of the containers must be

declared on the label and the contents must equal or exceed the amount

declared. Commercial canneries provide counterpoised scales and fill the

cans according to weight. During sterilization the weight will decrease

because of the shrinkage of the fruit in the sirup. The label must

therefore state the net contents based on weight of the fruit when the

can is opened after sterilization and this must be taken into account

when filling the cans.

Dr. A. W. Bitting has

done a great deal of work upon the net contents of cans of fruit and has

published tables showing the relations between the fresh weight of fruit

placed in the cans and the weight on the "cut out"; that is, when the

can is opened several weeks or longer after sterilization. The weight

immediately after sterilization will not be the same as that several

weeks after sterilization because of the equalization of sugar in the

sirup and fruit that takes place slowly after sterilization.

To determine the weight

of fruit in a can, the can is opened and the contents are drained on a

screen, or the top is cut and the fruit drained by inverting the can.

The contents are stated

either as net weight of fruit or as total weight of fruit and sirup.

The following table gives

the relation between the weight of fruit placed in the can before

sterilization and that some time after sterilization, for various fruits

and sizes of cans. The table is based on results published by Dr. A. W.

Bitting in Department Bulletin 196 of the United States Department of

Agriculture.

The weights of fresh

fruit in Column 4 may be taken as the proper amount to weigh into the

cans of this size before sealing, if the fruit is for market;- because

the figures were obtained upon fruits packed in the usual commercial way

and represent average conditions. The net contents to be published on

the label would be obtained from Column 5. Five hundred and fifty grams

corresponds to 183 ounces; 560 grams to 18% ounces; and 500 grams to 16%

ounces.

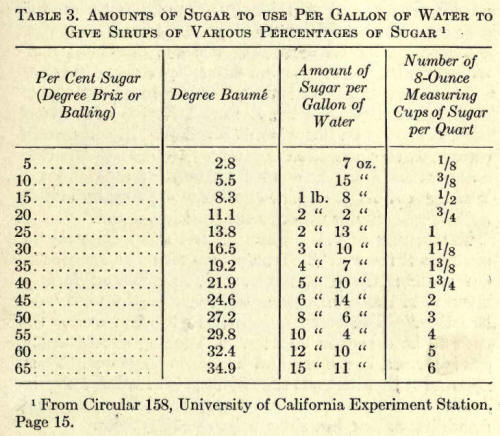

12. Sirups and

Hydrometers. In commercial canning, fruits are packed in the cans

before cooking. A sirup is added and the fruit is cooked in this sirup

in the can. The sirups are made to contain various percentages of sugar,

according to the various grades and varieties of fruit.

The sirups are tested

before use by means of a sugar hydrometer or saccharometer. There are

two general makes of hydrometers; namely, those which indicate the per

cent of sugar directly, and those which indicate the Baume degree, which

is approximately one-half the real per cent of sugar. The Brix and

Balling hydrometers indicate actual per cent of sugar.

The hydrometers consist

of a glass tube with a long narrow stem at the top and an enlarged lower

end weighted with shot or mercury. The upper stem carries a scale marked

either in per cent sugar (Balling or Brix degress) or in degrees Baume.

The instruments sink to 0 in water. Liquids containing sugar or other

materials in solution exert a greater buoyant effect than water and the

instrument rises in proportion to the amount of sugar present.

To use the instrument, a

tall glass jar or cylinder is filled with the sirup. A tall green olive

jar or a tall narrow flower vase will do for a cylinder. The hydrometer

is inserted and the degree indicated at the surface of the liquid is

read. (See Fig. 32.)

The sirup should be cool

when the test is made because high temperatures cause the reading to be

too low.

The hydrometer need not

be used in household canning. Sirups. can be made up accurately enough

for this purpose by making use of the following table. For each gallon

of water used in making the sirup weigh out the amount of sugar given in

Column 3 of the table and dissolve in one gallon of water. To use Column

4, measure out the amount of sugar indicated and dissolve in one quart

of water.

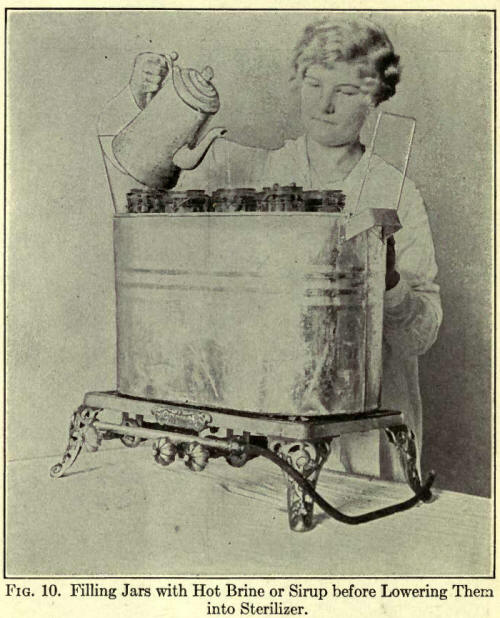

The sirup in home canning

is added boiling hot to save time in sterilizing and to avoid the

necessity of " exhausting." See paragraph 14. The sirup may be heated in

a teapot and poured directly into the jars or cans. It should be poured

down through the center of fruit packed in jars rather than against the

sides of the jar. This will prevent breakage. (See Fig. 10.)

13. Cane vs. Beet

Sugar. An unwarranted prejudice exists against beet sugar for

canning. Cane and beet sugar are one and the same thing chemically and

modern factory methods produce beet sugar of just as good quality as the

best cane sugar. Both are used in commercial canneries with equally good

results.

A number of years ago

beet sugar was in some cases poorly refined and occasionally of poor

flavor on this account. This condition no longer exists and beet sugar

can be used for canning, jelly making, preserves, marmalades, etc., to

just as good advantage as cane sugar.

14. Exhausting. If

fruit is put up in solder top or sanitary cans (see Recipe 1, Part III),

the contents of the can should be hot when it is scaled. In commercial

canneries, this condition is attained by heating the cans and contents

after the can is filled and before it is closed. The same effect is

obtained in home canning by adding boiling hot sirup or water to the

fruit in the can.

Exhausting or the

addition of hot sirup expands the contents of the can. The can is then

sealed and sterilized. On cooling, the contents contract again and form

a vacuum in the can. Hence the origin of the term "exhausting." The

vacuum formed in the can causes the ends to be drawn in slightly. If

spoiling should occur, gas is formed in the can and the edges bulge out.

Thus, a can of fruit with ends slightly drawn in is known to be good.

This is the principal reason for exhausting cans, or adding boiling hot

sirup before scaling them.

In exhausting solder top

cans, the fruit and sirup are placed in the can cold. The cap is sealed

on the can as directed in Recipe 1, but the vent hole is left open. The

cans are placed in boiling water to about three-fourths the depth of the

cans. A washboiler or other sterilizer can be used. They are left

approximately five to ten minutes depending on the size of the can. They

are then removed and the vent hole is closed or "tipped" with a drop of

solder. The can is then ready for processing.

To exhaust sanitary cans,

one proceeds as with solder top cans, but does not place the lid on the

can until after exhausting. Then it is sealed in a sanitary capper such

as the one shown in Fig. 13.

15. Sterilization of

Fruits. Sterilization is the destruction of all living

microorganisms in the product sterilized. It is usually accomplished by

heat and accompanied by hermetic sealing so that the contents of the

container will not become re-infected with microorganisms.

Fruits, because of their

high acidity, are easily sterilized by heat; a temperature of 165° F.

being sufficient. However, since it is usually desirable to cook the

fruit at the same time, the sterilization is carried out at the boiling

point, i. e., 212° F.

The old household method

consisted in cooking the fruit in a pot and pouring it boiling hot into

scalded cans or jars and sealing at once without further treatment. This

method is unsafe because often the jars and caps do not get thoroughly

sterilized by the hot fruit, and spoiling results.

Sterilizing the fruits in

the container is much safer and more economical of time and labor. Any

form of sterilizer in which the cans or jars may be subjected to the

temperature of boiling water for the desired length of time may be used.

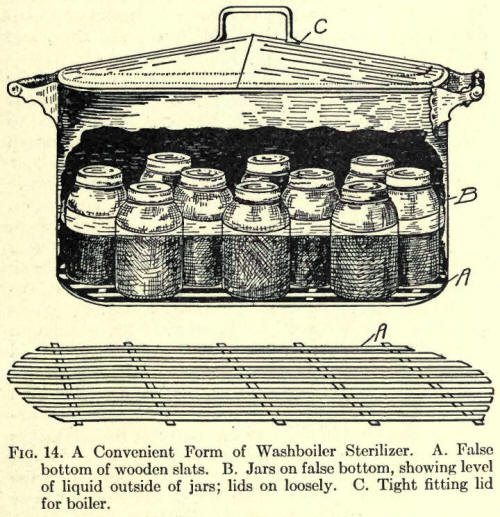

A very simple sterilizer

for home use may be made by placing a false slat or screen bottom in a

washboiler. The jars rest on this false bottom to protect them from the

direct heat of the flame. (See Fig. 14.) A very convenient frame for

holding jars in a washboiler may be bought in the form of a rack used

ordinarily for boiling clothes. Figure 16 illustrates such a rack. This

also acts as a false bottom. It is improved by soldering a wire guard on

the sides of the rack to hold the jars in place.

In using a washboiler

sterilizer the jars are filled with fruit and hot sirup or water is

added, the lids and rubbers placed on loosely, enough water is added to

the boiler so that when the jars are placed in it the water will rise to

about two-thirds the height of the jars, the water is heated to the

temperature of the jars or a little higher, the jars are placed on the

false bottom, the cover is placed on the boiler, the water is heated to

boiling, and boiled for the length of time desired for the particular

fruit to be sterilized. The time is counted from the time the water is

actively boiling. The tops of the jars are heated by the steam. If the

lid of the boiler fits imperfectly a towel may be placed between the lid

and boiler top to make the seal more perfect. (See Fig. 15.)

The jars after

sterilization are removed at once and the caps are tightened. If the

false bottom or rack is equipped with handles the removal of the hot

jars is greatly facilitated. Jar tongs may also be used to lift the jars

from the hot water.

The length of time of

sterilization will vary with different fruits and with the maturity of

the fruit. This variation is because of the differences in texture; not

because some fruits are harder to sterilize than others. Firm fruits,

such as certain varieties of clingstone peaches, and pears, require a

longer time than softer fruits, such as most freestone peaches and

plums. The length of sterilization for various fruits is taken up under

the recipes for each fruit.

Various forms of

commercially made sterilizers for fruits may be purchased. These give

satisfactory results and where very large quantities of fruits are to be

canned their use may become desirable. There are types of commercial

sterilizers designed primarily for the sterilization of vegetables and

meats under steam pressure, but which can also be used for fruits. These

are discussed under paragraph 21, Sterilization of Vegetables. (See Fig.

18.) |