|

Dried fruit is one of the

most concentrated of all fruit products and one of the simplest to

prepare. It requires no very expensive or special equipment when carried

out on a small scale.

Fruit is dried in two

ways: (a) by sun evaporation, and (b) by artificial heat. The former is

used in dry hot climates such as prevail in California and Arizona,

while the latter must often be used in climates where summer rains

occur. Both methods are discussed in the following pages.

60. Importance of the

Industry. Fruit is dried on a very extensive scale in California,

and in this state fruit drying is one of the largest horticultural

industries. It serves in this state both as a primary industry and as an

insurance against low prices for fruit grown primarily for canning or

fresh shipment. As in other states, a certain amount of cull fruit is

dried, but as a rule, the fruit used is the average orchard run. The

raisin industry in California amounts to 125,000 tons of raisins

annually, and is the largest of the state's dried fruit outputs. Prunes,

figs, peaches, pears, and apricots are also dried in large quantities.

The climate of this state is dry and hot without summer rains. This

permits drying in the sun and accounts for the size of the industry.

In other fruit growing

regions of the United States artificial heat is used almost exclusively

in drying. Drying fruit is one of the cheapest and most convenient ways

of saving surplus fruit crops. If well done the quality of the product

compares favorably with that of canned fruit.

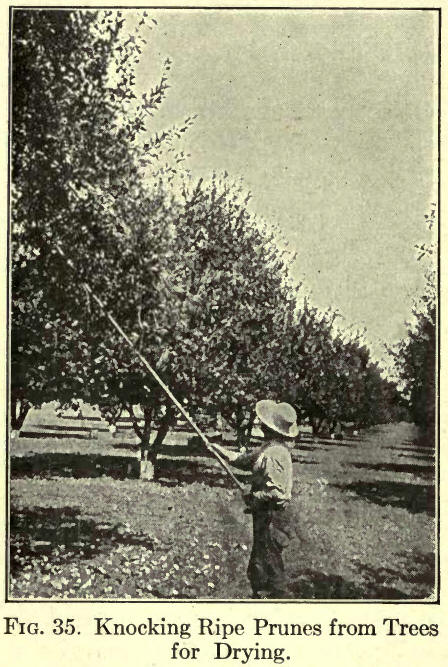

61. Gathering the

Fruit. Drying does not improve or disguise the quality of the fruit.

To obtain dried fruit of good marketability, a good grade of fresh fruit

must be used.

The stage of ripeness at

which the fruit is picked varies with the variety. Apricots are picked

firm ripe—if too ripe they will melt down to unattractive "slabs"; figs

and prunes are allowed to ripell until they drop from the trees of their

own accord; peaches are gathered when fully ripe, but while still firm

enough to permit handling; pears are picked when full size, but not yet

ripe, and are allowed to ripen in piles of straw before drying; grapes

are picked when fully ripe; apples for drying are usually the packing

house culls. The riper the fruit is, the more sugar it will contain and

therefore the larger the yield of dry fruit will be, unless the fruit is

overripe and so soft that excessive loss occurs.

62. Transfer to the

Dry Yard. The fruit should be taken quickly to the dry yard or

evaporator after picking and so handled that bruising does not take

place. Fruit for drying should be handled as carefully as fruit for

fresh shipment, if the best results are expected.

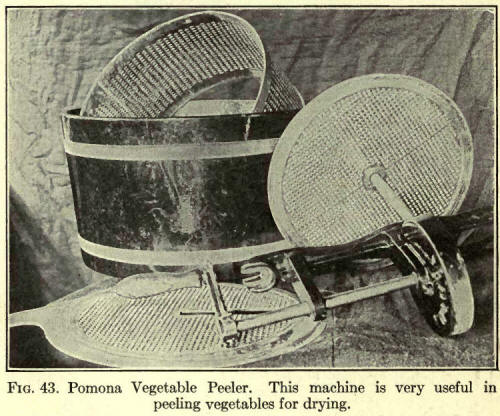

63. Cutting and

Peeling. Apples are peeled, cored, and cut into disks before drying.

Other fruits are usually dried without peeling.

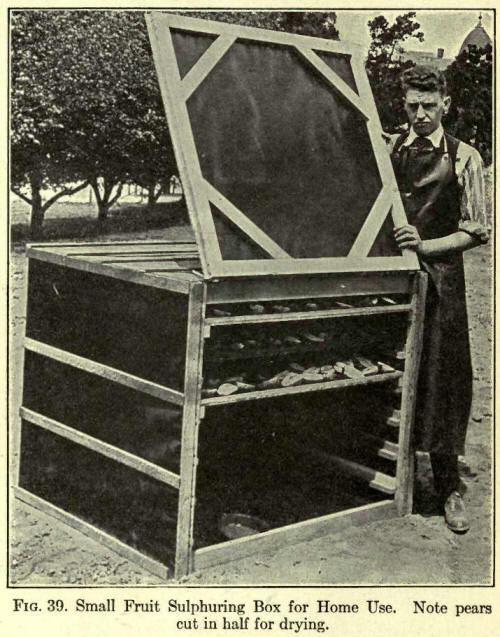

Peaches and apricots are

cut in half and pitted by hand. Pears are cut in half lengthwise before

placing on drying trays. They are not peeled or cored. Peaches are

sometimes peeled before drying by use of a hot concentrated lye

solution. The peaches are cut and pitted; then immersed in a boiling 10%

soda lye solution for a long enough time to soften the skin thoroughly.

They are then passed through strong jets of water that wash off the

softened skins and remove the lye adhering to the pit cavities. This

method of peeling is not easily used on a small scale and is only

recommended for large dry yards.

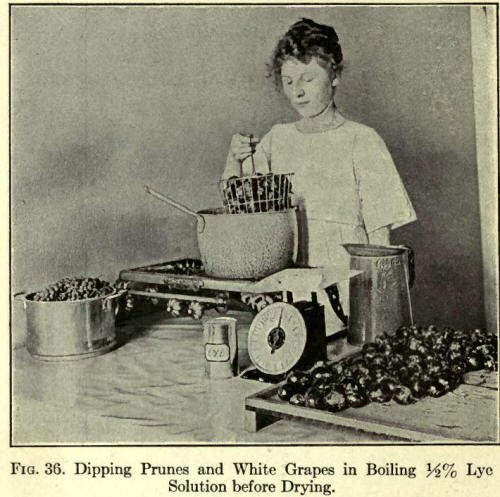

64. Dipping Fruits

before Drying. Prunes are dipped in a hot dilute lye solution a few

seconds to crack the skins before they are dried. The dipping solution

contains about 32% of lye or one pound per thirty gallons of water, for

the French prune, the one most commonly grown. The solution is more

dilute for the Sugar Prune and Imperial Prune, two less important

varieties. The prunes are held in a wire basket in which they are

irnniersed in the hot lye solution for five to thirty seconds, or they

are carried through the liquid in a perforated rotating drum. They are

often dipped in water or are passed through water sprays to remove

excess lye and adhering dirt. The dipping checks the skins sufficiently

to greatly increase the rate of drying.

Sultanina and Sultana

seedless grapes are often dipped in hot dilute (%%) lye solution or in

sodium bicarbonate solution to crack the skin slightly or to remove the

bloom to facilitate drying. The dipping in dilute lye is also carried

out in connection with the sulphuring of Sultanina grapes (Thompson

Seedless)It increases the rate of absorption of the sulphur fumes.

Grapes after dipping in hot lye are rinsed in cold water while those

dipped in cold sodium bicarbonate solution are not rinsed in water but

are placed directly upon trays to dry.

65. Sulphuring Fruits

before Drying. Fruits darken badly, unless treated with fumes of

burning sulphur before drying. The darkening is due to oxidation of the

coloring matter. Sulphur fumes prevent oxidation and darkening. In some

cases, for example in Muscat raisins and prunes, the dark color is

considered desirable; in others the dark color is objectionable.

Apricots, pears, apples,

and peaches are usually

"sulphured" before drying. Sulphuring should not be excessive, because

the flavor of the fruit is thereby injured and sulphuring should never

be employed to cover up defects.

In addition to preventing

the darkening of the color, the sulphur fumes act as mild a preservative

and tend to prevent the molding and fermentation of the fruit during sun

drying.

A great deal of

controversy has arisen in the past and a great diversity of opinion

exists at present as to the effect of sulphurous acid in food products

(sulphurous acid and sulphur dioxide are other names for the fumes of

burning sulphur). It is generally admitted that when large amounts of

sulphurous acid are eaten in food, injury to health results; but it is

extremely doubtful whether the relatively small amount eaten in cooked

dried sulphured fruits is harmful. Cooking drives off a great deal of

the sulphurous acid and little remains in the cooked fruit, unless the

fruit has been badly over sulphured.

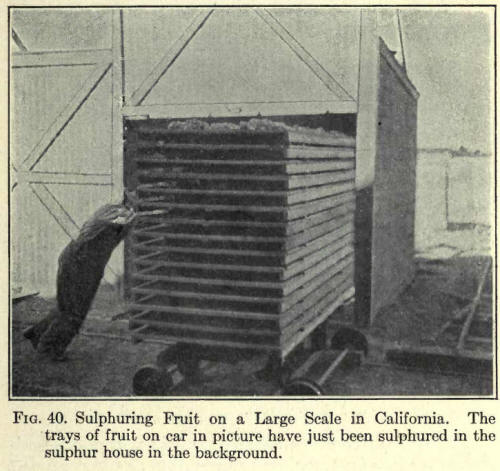

The sulphuring of the

fruit is accomplished by spreading it on drying trays and exposing the

fruit and trays to the fumes of burning sulphur for the desired length

of tine. The room or box in which the sulphuring is carried out is

commonly called a "sulphur box" or "sulphur house." It may be a small

house large enough to hold a small hand truck or carload of trays, or

may be so constructed that the trays may rest on cleats on the sides of

the sulphur box. A very convenient form is the so-called "balloon

sulphur hood." This is a light rectangular wooden or building paper

covered box that can be set down over a stack of about one dozen trays.

Sulphur is burned in a

shallow pit inside the sulphur box in the ground beneath the trays, or

in a container outside the box and the fumes are conducted into the box

by means of a flue. To ignite the sulphur, a small amount of excelsior

or a few shavings may be used. The sulphur should be kept burning

constantly for the length of time it is desired to expose the fruit to

the fumes.

Apples are sometimes

sulphured by passing them on a belt conveyor through a long box filled

with sulphur fumes. Sliced apples are sulphured for twenty to thirty

minutes; apricots, peaches, and seedless grapes, three to five hours,

and. pears, six to forty-eight hours. After sulphuring, the fruit is

ready for the dry yard or evaporator.

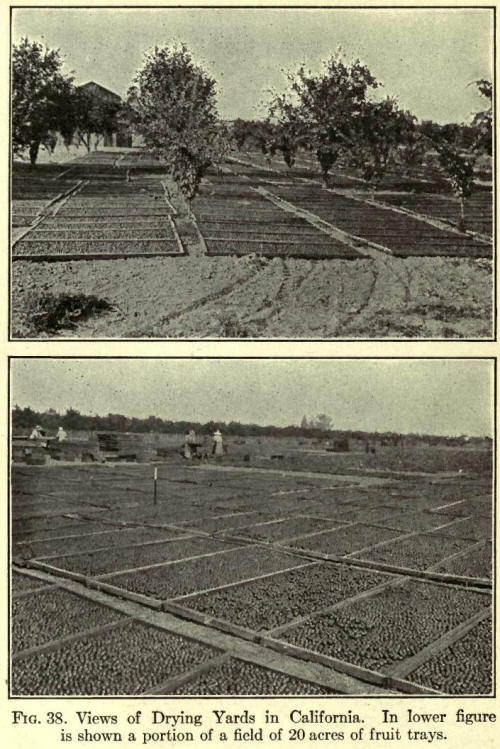

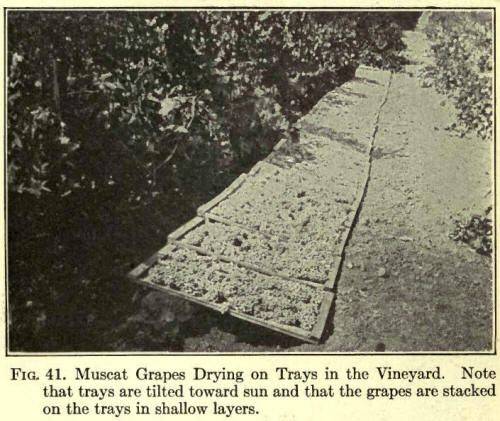

66. Trays for Sun

Drying. Wooden trays 2 x 3 feet, or 3 x 6 feet, or 3 x 8 feet are

used in sun drying fruits commercially. These are made of sugar pine or

other tasteless white wood. Redwood colors the fruit. Shakes 3" x 6" are

nailed to side strips and cleats are nailed to the ends. In long trays,

one or two narrow strips of wood are nailed lengthwise near the center

of the tray to act as a support.

For drying small amounts

of fruit, improvised trays may be used. Cloth or paper will answer the

purpose or the fruit may he placed directly on a flat roof.

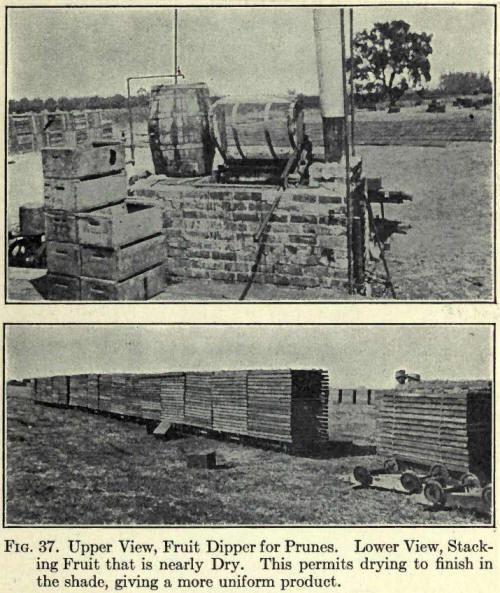

67. Sun Drying. A

dry hot climate, free from rains, is necessary for sun drying. Sun

drying requires less equipment and labor than drying by artificial heat.

There is more tendency for darkening of the fruit, for accumulation of

dust, and injury by insects or mold than is the case in artificial

drying. However, dried fruits of excellent quality are made by this

method.

The fruit after

preparation by cutting, dipping, peeling, spreading on trays, and

sulphuring, as the case may require, is then exposed to the sun on trays

that are placed on the ground. The drying yard should be clean and as

free from dust as possible.

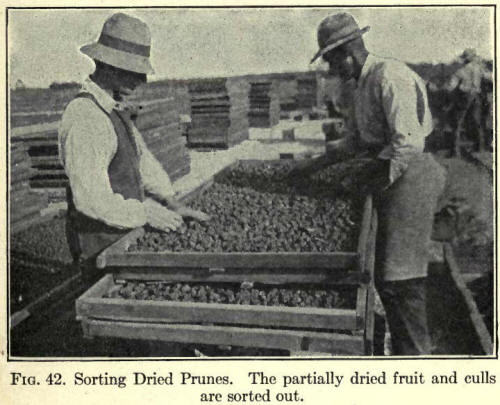

Grapes are turned when

about one-half dry by inverting a full tray over an empty one. Prunes

are stirred or turned several times during drying to cause even drying.

Other fruits are ordinarily not turned.

In case of a shower, the

trays are stacked in piles of a dozen or more trays each and covered

with empty trays or with boards to shed the rain. Late in the season

this often becomes necessary. During long rain storms or continued

cloudy weather, it is sometimes necessary to use artificial heat, or the

partially dried fruit must be

heavily sulphured to

prevent molding until there is again sufficient sunshine to permit

drying.

The fruit should not be

allowed to become too dry. The texture of the finished product should be

leathery, not hard and brittle. Excessive drying results in great loss

of flavor and makes the fruit difficult to cook.

The fruit will dry more

uniformly, the color will be better, and there will be less danger of

its becoming too dry, if the trays are stacked when the fruit is about

two-thirds dry. They should be stacked so that the air will pass freely

between them and complete the drying.

All of the fruit will not

dry at the same rate, and when most of it is sufficiently dry, it is

taken from the trays. That which is not dried sufficiently is left on

the trays a few days longer.

In good drying weather

most fruits are left four to six days in the sun, and about the same

length of time in the stack, making a total time of eight to twelve

days.

68. Artificial

Evaporation. The rate of removal of water by evaporation by sun or

artificial heat depends upon three factors: (1) temperature, (2)

humidity of the air, and (3) the rate at which the air passes over the

fruit. In many fruit growing sections, factors "1" and "2," or both, are

not favorable for sun drying, and artificial heat must be used.

Evaporators are of many

sizes and designs. An efficient dryer should take into account all three

of the above principles. The temperature in the evaporator may be raised

to about 115° F. for most fresh fruits and

140° F. for fruit that

is.almost dry. Temperatures much above this cause scorching and severe

darkening of color. Thermometers should be used to record the

temperature in the dryer.

The humidity or moisture

content of the air passing through the dryer is exceedingly important.

If air is saturated with water vapor it will not cause drying,

regardless of the amount used; therefore, the evaporator cannot be made

so long that the air passing through becomes oversaturated with

moisture. A rise in temperature greatly increases the power of the air

to absorb moisture. Thus air at ordinary temperatures may be saturated

with water vapor, but when heated to 140° to

175° F., will again be

able to take up a very large amount of moisture. It must not, however,

be allowed to cool before it leaves the dryer, or the cooling will cause

the excess moisture to condense on the fruit at the upper end of the

dryer. If, therefore, the air is well heated, it will be "dry" before it

goes into the dryer regardless of its previous moisture content when

cold.

The importance of the

volume of the air passing over the fruit is a point often lost sight of

in building dryers. Air soon becomes saturated with moisture. If it is

not replaced with fresh air at once, the saturated air passes over the

remaining fruit without causing drying. If the air is supplied more

rapidly than it becomes saturated with water, drying proceeds throughout

the whole dryer. The rate of absorption of water vapor is greatest when

the warm air first enters the evaporator and before it has absorbed very

much moisture. Therefore, if the volume of air passed through is very

large, the rate of absorption is greatly increased, because the air is

constantly in the condition in which it most rapidly takes up water.

With these principles in

mind, the artificial dryer should be built so that an even temperature,

dry air, and a large supply of air are maintained.

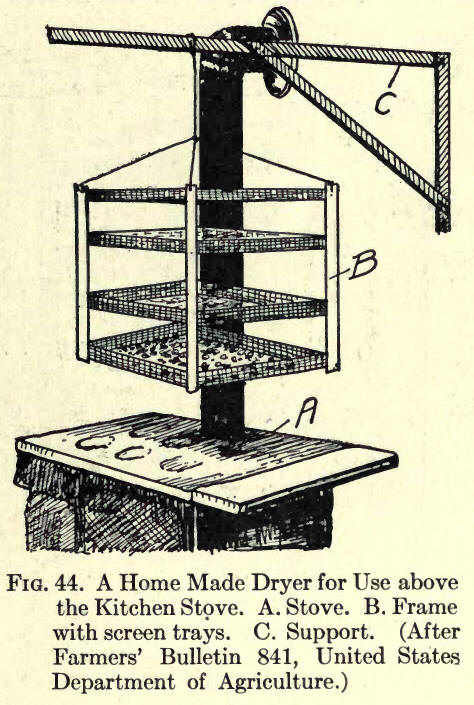

A simple dryer for home

use can be constructed from a few pieces of galvanized coarse mesh

screen. This is hung or placed on metal supports above the stove. The

dryer consists of several of these screen trays placed one above the

other at about three-inch intervals. (See Fig. 44.)

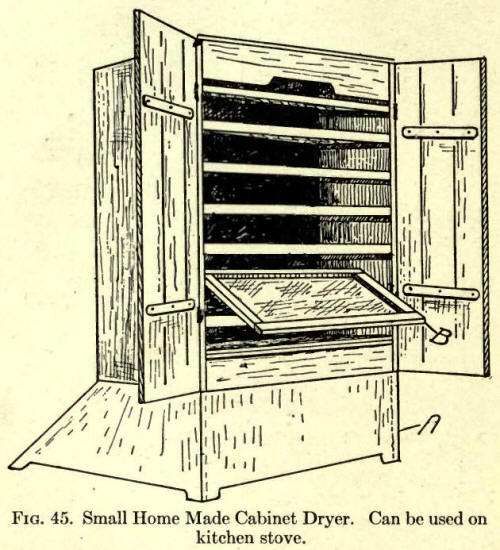

A small cabinet dryer can

be made of rough lumber, an old stove, and a few lengths of stove pipe.

(See Fig. 45.)

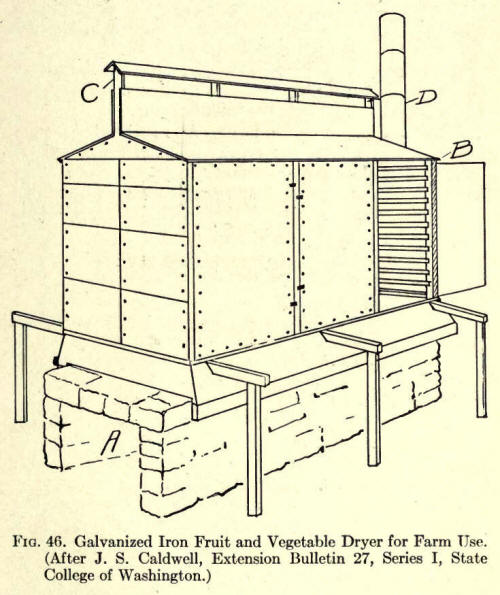

For larger scale drying,

several types of evaporators are in use. The kiln dryer is one of the

cheapest.. A floor, usually 20 x 20 feet, made up of wooden strips with

spaces between for passage of hot air, forms the drying surface on which

the fruit is placed. Beneath the floor the flue or stove pipe from the

heater is placed. This is led back and forth across the dryer several

times to distribute the heat tinder the entire floor. A roof with a

large ventilator completes the dryer.

The tunnel dryer consists

usually of a wooden chamber 12 to 18 feet long and 6 x 3 feet in cross

section. It is sloping. Hot air flues pass beneath it. The trays slide

in on runways at the upper end and are taken out at the lower end. The

entering tray displaces one at the lower end. This dryer is used a great

deal for berries and prunes in the Pacific Northwest.

The cabinet evaporator

consists of an upright heating chamber into which the trays fit one

above the other. Heat is supplied at the bottom from hot flues or from

steam pipes. The fresh fruit is placed at the top. As a new tray goes

in, a tray of dried fruit is taken from the bottom of the stack, the

whole stack of trays automatically dropping the height of one tray. This

form of dryer is used in some apple drying sections.

The air blast evaporator

is one of the most satisfactory types. It is used for grapes and prunes

during rainy weather in the central portion of California. It consists

of a long narrow room the width of an eight-foot tray. At one end is a

large air fan. Back of the fan is a series of very hot flues. The trays

are stacked on trucks and run into the long chamber through side doors.

The fan draws the hot air over the flues and forces it through the

drying chamber over the fruit. The rate of drying is rapid and the

maximum efficiency of the heat is obtained because of the large volume

of air used.

Specific directions for

temperatures of drying, etc., for various fruits will be found in

recipes in Part III.

69. Sweating.

Fruit dries unevenly, some pieces being hard and dry and others not

quite dry enough when the bulk of the fruit has reached the desired

stage of dryness. The moisture content of the outer layers of the fruit

is less than that of the center of each piece. The moisture content is

equalized by storing the fruit in bins or large boxes for a time to

undergo " sweating," which is nothing more nor less than equalization of

the moisture. The sweat boxes or bin must be protected from insects and

should be kept dry and cool. The fruit is left in the sweat boxes about

two weeks, or until packed for final storage or market.

70. Processing and

Packing. Fruit dried in the sun usually becomes infested with

insects or insect eggs which would later produce larvae with resulting

loss of the fruit. Often the fruit may become too dry or may he dusty.

Treatment of the fruit

with boiling hot water for a short time will overcome the above defects.

This may be accomplished by placing the fruit in a wire basket and

immersing it in boiling water for about one minute. If it has been very

dry it may be packed at once; if only medium dry it may be necessary to

allow it to dry on trays a short time before packing.

Apricots, peaches, and

pears are sometimes sulphured for one to three hours after dipping in

hot water. This is often done to permit the fruit to absorb large

amounts of water without fermenting or molding—the sulphurous acid

acting as an antiseptic. Its use is not to be encouraged in treating

dried fruits for this purpose.

The packing of dried

fruits is an extensive industry, requiring rather elaborate and

expensive machinery and a variety of processes, which cannot be

described or discussed adequately in this volume.

Raisins are dried to an

almost anhydrous state at the packing house; are then stemmed in a

special machine; processed in hot water; and the raisins with seeds are

seeded in a complicated seeding machine.

Prunes are graded for

size according to number per pound. The seller is paid on a basis of

eighty prunes to the pound. He is penalized for all prunes requiring

more than eighty to the pound and is paid a premium for those requiring

less than eighty to the pound. After grading they are processed in hot

water and packed.

Dried fruit for market is

usually packed in paraffin paper lined wooden boxes of 20 to 50 pounds'

capacity, or in paper cartons of half pound to one pound size. Packed

fruit brings much better prices than bulk dried fruit. Attractive

packages are essential for successful marketing.

Dried fruit for home use

should be stored in insect-proof containers, away from rodents. Paper

bags, tight boxes, jars, etc., can be used. Ordinary cloth or burlap

bags are not suitable, because it is possible for insects to deposit

eggs through these.

A dry place should be

selected so that the fruit will not become moldy. |