|

Reviewed by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Atlanta, GA.

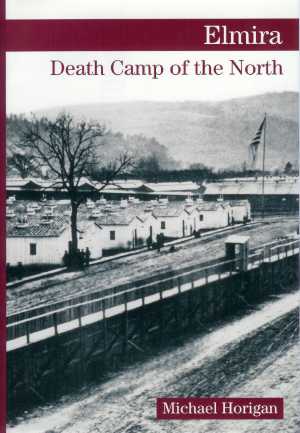

On

July 6, 1864, a prison camp known as Elmira (New York) opened for

business. In its one year of existence during America’s Civil War (369

days), records confirm that 12,123 Southern prisoners-of-war were guests

of the infamous Barracks No. 3. It closed 12 months later on July 11,

1865. Unfortunately 3,000 of the POWs never made it out alive. This high

death rate, almost 25%, was the largest in any prison camp in the North

and rivaled the death rate of the infamous Confederate POW camp in

Andersonville, Georgia. On

July 6, 1864, a prison camp known as Elmira (New York) opened for

business. In its one year of existence during America’s Civil War (369

days), records confirm that 12,123 Southern prisoners-of-war were guests

of the infamous Barracks No. 3. It closed 12 months later on July 11,

1865. Unfortunately 3,000 of the POWs never made it out alive. This high

death rate, almost 25%, was the largest in any prison camp in the North

and rivaled the death rate of the infamous Confederate POW camp in

Andersonville, Georgia.

I find it ironic that the author uses a

quotation from Willie Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar that I

learned in Mrs. Grimes’ 11th grade Lit class which really says

it all: "The evil that men do lives after them, The good is oft interred

with their bones".

This riveting story is by a native son

of the North, a former lecturer and American History teacher for over 20

years at Horseheads High School in Elmira. Michael Horigan is a recognized

expert on the Elmira prison camp and has the credentials to back up that

statement. He served on the advisory committee to construct a camp

memorial at Elmira, and his material was used in a Public Television

documentary, Helmira: 1864-1865. Horigan, author and

historian, has opened some old wounds with some new insights. He gives

reasons that the camp became known as Helmira. The death rates at both

Elmira and Andersonville were similar, and the worst part of it all was

that "the atrocities committed by Americans against Americans" on both

sides, I might add, did not have to happen. What was different about the

two death camps was how each side carried out the atrocities.

The real life characters in this book

would be hard pressed to have someone write a script for Hollywood that

followed the actions carried out during the life of this camp, clandestine

or otherwise. You will see capitalism at its worst - tickets to an

observatory were sold for citizens to view the Southern prisoners.

"Where’s the beef?" was a question asked at Elmira long before the Burger

King ad. Connect the dots when you finish this great book, and you will

find "the invisible hand of the Secretary of War", Edwin Stanton,

everywhere.

During the first three months of 1865

(the time it is estimated that my own grandfather arrived at Elmira),

1,202 Confederate soldiers died at Elmira. That is 40.3% of all deaths

during the 369 days the POW camp existed. Clothing for the "destitute"

prisoners sent north by family and friends was not allowed to be delivered

to the prisoners. You’ll find that "…an unstated policy of retaliation was

in place at Elmira…" and that it was carried out by the powers that be.

Smallpox ran rampant beginning in

October of 1864, lasting for six months, and the smallpox hospital was a

"misnomer" since it consisted only of tents where the "men who died were

dragged out and left in front of the tents". Some prisoners, unable to

purchase vegetables with money sent to them by relatives, killed rats for

food while others killed and ate dogs and cats. Those caught eating a dog

were forced, in all kinds of weather, to wear a "barrel shirt" with a sign

proclaiming, "I eat a dog" or "Dog Eater". Probably the most denigrating

sign was one that read, "I stole my mess-mate’s rations".

These are some of the many conditions

that Michael Horigan has brought to our attention. They beg to ask the

great question, "Who was responsible for this state of things?" which

happens to be the title of Chapter 8. I will not answer that question for

you. Suffice it to say that the death rate at Elmira was eight per day for

the 369 days the camp was in existence. The author tells us that "almost

all of Elmira’s survivors agree that the villain" was …

Sharing this book has been the most

personal journey I have taken with you since beginning my book review

column nearly four years ago. I never knew my Grandfather, Pvt. John W.

Shaw, CSA. He died in 1911; I was born in 1938 to his son, Charles

Bascombe. I never recall my father talking about Grandfather’s time at

Elmira. I was too young to be aware of Pvt. Shaw’s record, but if he was

alive today, I’d sure like to know his answer to the above question. Since

I was 14 when my father died in 1953, I never knew him man to man. If I

had, however, I would have asked him what his father had to say about

Elmira.

I do have a copy of the muster roll from

the North Carolina Archives where Grandfather Shaw made his mark when he

signed on to fight for the South. The ten children of Charlie and Mattie

Shaw are lucky our Grandfather survived Fort Fisher where 25% of the

soldiers fell defending the fort and another 24.3% died as prisoners at

Elmira. But, in conclusion, I’ll tell you this - I’m proud that John

Washington Shaw was not a slave owner, and I’m just as proud he fought for

what he believed, whatever it was he believed. After all, fighting for our

beliefs is one reason we are a great nation today! (8-26-03) |