|

Edited by Frank R.

Shaw, FSA Scot, Atlanta, GA,

jurascot@earthlink.net

22 Days - An Highland Immortal Memory

I recently received an email from a gentleman

named Ian MacMillan who lives in Fernbank, Laide Wester Ross,

Scotland. His wife, Jean, inherited a croft from her aunt and

uncle, and the couple moved there three years ago following his

early retirement. Ian has been a Burns’ enthusiast all his life,

encouraged first by his father and then in school. He is

well-known as a Burns Night speaker, and he says he is probably

best known for his delivery of “To a Haggis”, “To a Louse”, and

most recently “Holy Willie”. There had not been a Burns Supper

in that part of Scotland for a long time, so he established the

Wester Ross Burns Club, and they celebrated their fourth annual

Burns Night Supper this year. Ian and two of his buddies created

a one-hour program about Robert Burns’ 22 day tour of the

central and northeast Highlands in 1787 when Burns was 28 years

old. The program has played on three local radio stations

covering two lochs, Wester Ross, Skye and Ayrshire on Burns

Night.

I

hope this encourages some of you who are so inclined to send me

your articles on Burns that you have either published or used as

a speech before a Burns Club or other Scottish events. It is

with pleasure that we have Ian’s program for our enjoyment. If

you wish to contact him, his email address is

Scampmacmil@aol.com.

22 DAYS – A HIGHLAND IMMORTAL

MEMORY

By: Ian MacMillan, November 2005

Ian MacMillan as Holy Willie

It is the norm when paying tribute to our Bard to

try, in some way, to cover his short span of 37 years and his

incredible achievements over that time.

I am

not going to do that. I am going to concentrate on a period of

just 22 days in his life. My three reasons are:

(1)

During the 22 days, he offended the King; had a lord plant trees

all over a glen; was inspired by visits to famous sites of

Scottish events and heroes; decided to change from poems to

songs; met up with his father’s family; dined with lords,

ladies, bishops and professors – so a reasonably interesting

three weeks.

(2)

He traveled a huge distance over the central and northeast

Highlands of Scotland. It is estimated that, including all the

windings, the to and fro diversions on his tour, he covered some

600 miles in a coach taking notes for later works. An amazing

distance considering that in those days it took him two days,

including an overnight stop, to get from his Ayrshire home to

Edinburgh. Back in the late 18th century, many roads

were tolled, involving delays, and were very rough and unpaved.

He wrote of this in his Epigram on Rough Roads:

I’m now

arrived – thanks to the gods –

Thro’ pathways rough and muddy,

A certain sign that making roads

Is no this people’s study;

Altho’ I’m not wi’ Scripture cram’d

I’m sure the Bible says,

That heedless sinners shall be damn’d

Unless they mend their ways.

(3)

His tour was to the Highlands. As I prepared this

tribute far north of the line the Roman’s ‘darnae’d’ cross, it

seems most appropriate to concentrate on this one of his

journeys in those far-off days.

The year is

1787. Rabbie is 28. He had arrived in Edinburgh just 11 months

prior to a heroes welcome. Instead of emigrating to the

sun-kissed Caribbean with gorgeous Highland Mary, he had decided

to go to Edinburgh. That is a very difficult decision for any

Glaswegian to understand! Fans of his Kilmarnock edition had

persuaded him to compile a second, larger edition of his works.

His local publisher would not fund this, to his own later

lifelong regret, so off to the capital of Scotland.

Address to

Edinburgh

Edina Scotia’s

darling seat!

All hail thy palaces and tow’rs,

Where once beneath a Monarch’s feet,

Sat Legislation’s sovereign pow’rs!

No

doubt this kind of flattery helped in that he was lauded by the

great, the good and by the ordinary people of that city. His new

Second Edition was hugely popular. The list of subscribers ran

to over 38 pages. They included some of the most important

figures running the country, several of whom ordered over 20

copies. He was greeted hugely in lords’ chambers, ladies’ salons

and to uproarious evenings in local taverns. He was proclaimed

as ‘Caledonia’s Bard, Brother Burns’ by the Grand Master at a

meeting of all of the Mason’s Grand Lodges of Scotland. He said

it was all ‘enough to turn a poor poet’s head.’

As

anyone in business knows, artist or not, it is all very well

producing great works, but it is a different matter getting paid

for it. Burns was no exception. His publisher, Creech, was, to

say the least, in no hurry to pay; in fact, it took six months

before final accounts were settled.

Rabbie decided he could afford the time to visit some famous

people and places and to garner material and thoughts for future

work. He planned out a Highland tour. I don’t know how much he

was looking forward to it. On his only previous excursion north,

he had been very offended in Inverary, the seat of the Clan

Campbell. The innkeeper was so busy serving the Duke and his

company of anglers that Rabbie, whom he failed to recognize, was

turned away. His revenge was, of course, at once cut into a

window pane.

Whoe’er he be

who sojourns here,

I pity much his case.

Unless he comes to wait upon

The lord, their God, 'His Grace'.

There’s naething here but Highland pride,

And Highland scab and hunger,

If providence ha’ sent me here,

Was surly in an anger.

He

also had to part with his faithful old mare, Jenny Geddes. His

travelling companion, Willie Nichol, was no horseman and

insisted they share the cost of a coach and driver. Burns noted

sadly, “Jenny Geddes goes home to Ayrshire with, as my mother

used to say, her finger in her moo’.”

We

don’t know why Burns decided to select such a companion. Willie

Nichol was a master at Edinburgh High School, a Latin scholar,

and a student of literature. He also was a very prickly fellow,

as we shall see later. They set out from Edina on the 24th

August on a tour which in present terms would be over to

Stirling, then north up the A9 to Inverness. Then across the A96

east to Aberdeen via Buckie, and back down the east coast

visiting Rabbie’s father’s relations on the way back to the

capital.

Their first stop was to see Carron Ironworks. The porter would

not open the gates, as it was a Sunday. So he wrote on a window

of the Carron Inn the following poem with his diamond stylus, a

present from the Earl of Glencairn:

We cam na

here to view your works,

In hopes to be mair wise,

But only, les we gang to hell,

It may be nae surprise…

Then

on to Bannockburn. Burn’s diary entry said tersely, “Come to

Bannockburn, shown the hole where glorious Bruce set up his

Standard.”

This

event was believed to be one of the inspirations which led to

‘Scots, Wha Hae’, Bruce’s address to his army before

Bannockburn. Then onwards to Stirling where Burns was inspired

by a visit to the castle and the view over to the ruined ancient

hall where the Scottish kings used to hold their Parliaments.

That night in James Wingate’s Inn (now the Golden Lion Hotel),

Rabbie’s romantic attachment to Jacobism soared as the level in

the glasses plummeted. As was his wont, he scratched the

following imprudent lines onto a window pane about the house of

Hanover:

‘An idiot race

to honour lost

Who know them best despise them most.’

Burns later returned and destroyed his work but too late as it

had already been gleefully reported in the newspapers as further

evidence of his lack of loyalty to the Crown. Next to Crieff,

then Dunkeld. There he met Neil Gow, the famous Scottish

fiddler. They talked songs all day. The old man was taken aback

at the extent of Burn’s musical knowledge and of Scottish songs.

We think that from here on Burns became increasingly more

interested in writing songs rather than poems.

Next

he travelled on to Blair Castle where he had been invited to

stay and dine with the Duchess. Burns was made most welcome by

the Duke of Atholl, the Duchess and her two stunning sisters. We

can admire the beauty of one of them, Mrs. Graham, whose famous

portrait by Gainsborough hangs in our National Gallery. The

girls hugely enjoyed his company, and no doubt his flattery, so

they tried to persuade him to lengthen his stay. But his

companion, envious at the attention given to Rabbie rather than

himself, would have none of it. The girls even sent a servant to

try to bribe the coachman to loosen a horseshoe, but he proved

to be an incorruptible Scot.

This

was Burns’ first experience of Willie’s jealousy and

irascibility which was to plague the rest of their tour. Burns

said later, “It was like travelling with a loaded blunderbuss at

full cock.”

The

Duke persuaded Rabbie to make a diversion, as he travelled north

the next day to visit the Falls of Bruar some six miles on,

where the stream coming down from the mountains passes through a

rocky gorge to join the River Garry. Rabbie did so, and finding

the falls entirely bare of woods, wrote some lines entitled

The Humble Petition of Bruar Water in which he makes

the stream entreat the Duke to clothe its naked banks with

trees. The then Duke, an artist, complied willingly, and planted

out woods around the waterfall which you can see to this day. If

you visit the House of Bruar, a signpost takes you on a walk

through these woods to the waterfall.

Next

they stayed overnight in Dalwhinnie where a commemorative plaque

has recently been placed in the local inn. They then battled

through snow, said to be 17 feet deep, to Aviemore. This was in

early September, and we complain about the weather! Mind you, it

might have saved the skiing industry!

He

travelled on to Inverness where he stayed overnight in the

Ettles Hotel, Old Bridge St., Inverness, now the Town House, and

dined in Kingsmill House. He visited the battlefield at

Drumossie Moor which, just 21 years on from Culloden, must have

been a very poignant and troublesome place for a poet,

especially one with some Jacobite sympathies, even if they were

just romantic. He summed up his own feelings in The Lovely

Lass o’ Inverness:

The lovely

lass o’ Inverness

Nae joy nor pleasure can she see;

For e’en to morn she cries, ‘Alas’

And aye the saut tears blin’s her e’e.

Drumossie

Moor, Drumossie day,

A waefu’ day it was to me!

For there I lost my father dear,

My father dear and brethren three!

Their

wining sheet the bloody clay,

Their graves are growing green to see;

And by them lies the dearest lad

That ever blest a woman’s e’e!

Now wae to

thee thou cruel Lord,

A bloody man I trow thou be;

For monie a heart thou has made sair,

That ne’er did wrong to thine or thee!

Next

it was off to Fochabers where they visited Castle Gordon. The

vivacious Countess was a leading figure in Edinburgh society.

She and Rabbie had got on extremely well, and she had been very

keen to entertain him. After a few glasses of wine, Burns was

asked to dine with the company. He claimed that he’d forgotten

all about the fact that he had a travelling companion (I wonder

if this was not deliberate.). The Duke instantly offered to send

a servant to invite Nichol to join the company but Burns,

knowing that this would create even more offence, set off to

invite him himself. It was to no avail. Willie, by now furious

at being slighted again as he saw it, was pacing up and down

furiously, berating the poor coachman. Nothing could prevail on

him, so Rabbie, with much regret, had to turn his back on his

exalted friends in Castle Gordon where he had promised himself a

few pleasant days. He was as taken with the Duchess as she with

him so, by way of an apology, he sent her poems, including

On the Duchess of Gordon’s Reel Dancing:

She kiltit

up her kirtle weel

To show her bonie cutes sae sma’

And walloped about the reel,

The lightest leaper o’ them a’!

While

some, like slav’ring doited stots

Stoit’ring out thro’ the midden dub,

Fankit their heels amang their coats

And gart the floor their backsides sub;

Gordon,

the great, the gay, the gallant,

Skip’t like a maukin owre a dyke:

Deil tak me, since I was a callant,

Gif e’er my een beheld the like!

The

coach took them to Duff House in Banff. Their guide, George

Imlach, a local schoolboy, was asked if he had heard of Rabbie.

He replied, “Oh aye, we hae his book at hame.” He was then asked

to name his favourite Burns poem. He replied at once, “The

Two Dugs and Death and Doctor Hornbrook,

although I like The Cottars Saturday Night best

because it made me greet when my faither had me read it tae my

mither.”

At

this, Rabbie, who hadn’t spoken, put his hand on the boy’s

shoulder saying, “Weel my callant, I don’t wonder at your

greeting at reading the poem; it made me greet mair than aince

when I wis writin’ it at my faither’s fireside.”

That

gives us just some idea of the popularity of the Bard’s work.

That a schoolboy in Banff, so far north from Ayrshire, should be

so familiar with his work, just 14 months after his Kilmarnock

edition was published. Years later, George was still recounting

the tale of this meeting.

Next

it was on to stay in the New Inn in Castle Street, Aberdeen.

Here Burns met a whole crowd of notables, including Prof. Thomas

Gordon and Bishop Thomas Skinner. The latter was the son of the

author of Tullochgorrum which Rabbie proclaimed to

be the best Scottish song ever. He later corresponded with the

father, and from records we know he asked him if he would

“assist with a collection of auld songs I’m making on these

journeys for posterity.”

Dunnotar Castle, just south of

Stonehaven

Then

it was onto Stonehaven for a few days with cousin and aunts on

his father’s side. Rabbie was eager to learn all he could about

his paternal history. How, following the Jacobites’ march north

through their lands on the way to Culloden, his father and his

brothers had to leave their farm at Clochnahill near Dunnotar.

Next stop to meet his cousin in Montrose. Here, one of his

father’s brothers had begun a dynasty of lawyers named the

Burness clan. Then, finally, back to be rowed across the Forth

to Queensferry and returned to Edinburgh on the 16th

September. I would have thought he must have been exhausted. To

have covered such a long distance by coach in these times, with

all these stops and experiences, also with such a frustrating

companion.

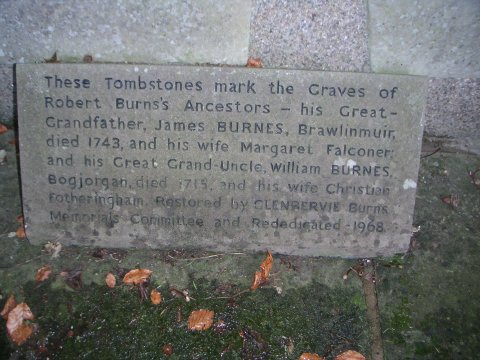

Marker at graves of Robert Burns'

ancestors

He

may have started off on his Highland tour offended at a duke,

but perhaps his enjoyment of the hospitality he experienced

throughout this long tour and his feelings about these 22 days

is better represented by the following lines:

Epigram on

Parting with a Kind Host in the Highlands

When death’s

dark stream I ferry o’er,

A time that surely shall come,

In Heaven itself I’ll ask no more

Than just a highland welcome!

References

-

Burns

by Principal Shairp, MacMillan and Co. Ltd., 1909

-

On the Trail

of Rabbie Burns

by John Cairney, Luath Press Ltd., 2000

-

The Complete

Poems and Songs of Rabbie Burns,

Geddes and Grosset, 2000

-

Burns

Chronicles published by The Robert Burns World Federation

Ltd.

|