|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

While this site was started over a decade ago as

book review space for Scottish books, I must confess “the times, they are a

changin” and I find myself working with a blog by good Burnsian friend

Stephen Hammock. This web site has evolved from book reviews into “Chats

with Authors”, a couple of Scottish prayers, tributes to old friends, and

trips to Scotland and Paris and, sadly, an obituary or two among the

articles. But this is my first attempt in dealing with a blog. I was so

impressed by Stephen’s work that I post here it in the hope that some of you

will be inclined to sign up and view the paths he will be following in the

years ahead in the States and in the United Kingdom.

Stephen Hammock is studying at Oxford University

for a doctorate and has now completed his first year. He spent the summer

months back in Georgia and recently returned to Oxford for the next step in

search of his degree. He is a bright young man and we came to know each

other when he joined the Burns Club of Atlanta. In our last email exchange

he said, “I need to add an article on Burns sometime!” That is something all

of us would like to read, Stephen, so I will hold you to it! Best wishes for

a great year at Oxford and thanks for sharing ramblingmuser with our

readers.

(FRS: 9.26.13)

ramblingmuser

literature,

archaeology, philosophy, exploration

←

Older posts

Posted on

September 9, 2013

by

shammock2012

Highgate Cemetery in London, England is a PHANTASTIC treasure

of Victorian sculptural sepulchres. A recent visit confirmed my hopes and

expectations, although I must say that the overly engineered tour was a bit

heavy-handed and I wish it had been possible to just wander around freely.

Since black and white photos of Highgate seem to do it the most justice,

here is a visual tour of it as nineteenth century photographs might have

depicted it.

George Wombwell

Monument

The Angels of Highgate

Highgate Cemetery

Path

The biggest regret was that the tour group was not taken to

see the grave of Elizabeth Siddal, the Pre-Raphaelite muse of Dante Gabriel

Rossetti, which we were looking forward to with excitement. Rossetti is

rumoured to have painted thousands of paintings of Siddal, whom he later

married, including the sensual Beata Beatrix, and his sister Christina once

described his obsession with this muse in verse. When she died in 1862,

Rossetti buried his sole surviving copies of his poems with her, an act

which he later regretted. Another regret that haunted him for the rest of

his life was the fact that he had her exhumed so he could reclaim the poetry

and publish it. It is said that her flowing red hair had somehow continued

to grow after her death, and that the coffin was overflowing with it….

Beata Beatrix by

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

“One face looks

out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.”

Christina Rossetti,

In An Artist’s Studio, 1856

Categories:

Cemeteries,

Exploration,

Literature

|

Tags:

cemetery,

Highgate,

London,

Victorian |

Posted on

July 25, 2013

by

shammock2012

Beatrice Addressing Dante from the Car by William Blake

Thomas Carlyle wrote that the greatest poets are also

prophets, and experience life on quite another sphere than their fellow

mortals. Though others may forget the sacred mysteries of life and come to

believe in appearances alone, the true poet cannot forget them because he

lives in them and is completely honest and dedicated to their universal

power. Homer, Dante, and Shakespeare, surely our three greatest poets,

support this idea of the poet/prophet, or Vates, and if we would seek to

understand such genius, we would do well to contemplate this truth – that

they are attuned to a key that the masses of men cannot or will not hear. It

is this that makes them unique even among poets, who are all commonly

regarded as having more sensitive natures, and it is this that also makes

understanding them a greater challenge.

Of these three most universal of poets, Dante alone combines

spiritual depth with intellectual vigor and intense lyrical sweetness.

Although he began writing in the Courtly Love tradition that swept across

Europe in the Middle Ages – a tradition invented by the troubadours of

southern France – Dante transformed this tradition when he wedded to it the

dolce stil nuovo (sweet new style), a literary movement popular among

Italian poets of his time. The primary characteristics of this style of

poetry were not only introspection, puns, and philosophical themes, but also

an insistence that the beautiful women about whom these poets wrote were

actually angelic beings. Dante took this last theme a step farther than any

of his contemporaries by insisting that one angelic lady in particular was

literally sent to Earth to show him the way to Heaven. He describes her and

his love for her in his poetry manual La Vita Nuova (The New Life) and in

his great epic The Commedia (The Comedy). The rest of this essay will

explore the life and ideas of this Mediaeval Italian Vates.

Dante was born in Florence in AD 1265 into a noble but

impoverished family. His father made a decent living by leasing out family

farmlands just north of the city. Although Dante had the advantages of an

urban education and manners, and was fiercely devoted to his hometown,

descriptions of country life also fill his poetry and show how deeply Nature

touched his great spirit. However, the central event in his life occurred on

May 1, 1274, when he was about nine. This is when he met eight year old

Beatrice Portinari at a party given by her father, and from that day forward

love fired his young heart. Soon he began to seek her out in the markets,

churches, and streets of the neighborhood where they lived, and although he

probably never knew her well, Dante came to see in Beatrice his ideal lady

of beauty, grace, and piety, and wrote a number of sonnets and poems in her

honor. In fact, her very name comes from the Latin Beatrix, and literally

means “one who makes happy.” Tragically, Beatrice died in 1290 at the age of

24.

Dante wrote a few more poems for her, combined them with

prose explanations of how he came to write them, and set them forth around

1295 under the title La Vita Nuova. Though he appears to have tried for a

while to forget her, her image was so emblazoned on his mind that he ended

up making her the central figure of his poetry and of his life. Over time

she has become the most memorable literary character in world history. For

it is certain that the immortal figure we meet in his writings is an

idealized version of the real girl he loved, and who married someone else

and died young. Dante also married, but, as was customary in Mediaeval

Europe, his was arranged by his family when he was about eleven. The

contract was fulfilled in late 1287, and four children resulted from this

union.

Dante studied philosophy and theology deeply in the years

after Beatrice’s death, and immersed himself in the Republic of Florence’s

politics from 1295-1301. Perhaps he became too involved in the factional

struggles that continually rocked his native city throughout the 13th and

14th centuries, but things came to a head when he became outspoken against

the secular politics of Pope Boniface VIII. Boniface was attempting to

increase the power of the papacy, and sought to undermine any Italian

city-states that were independent of his authority. His stratagems were but

one episode in the Middle Age struggle between the popes and the Holy Roman

Emperors, who argued that popes had power only over religious matters, while

the emperors controlled all secular matters. All Florentines nominally

supported the church in its endeavors and wars against the empire, but some,

like Dante, thought that Florence’s independence was more important than

serving either master too well. In this regard, Dante was sent as papal

ambassador to Rome in 1301 to argue for his city’s continued freedom. Though

the other Florentine ambassadors were soon allowed to leave, Boniface,

fearing Dante’s eloquence, purposefully delayed his return until the faction

supporting papal authority had time to violently wrest control of the city

from Dante’s party. Dante would never forgive Boniface for this, and would

later blacken the pope’s very name in a manner unique in the history of the

papacy. Dante was ultimately exiled from Florence and condemned to death by

his political enemies. However, the fame of his poetry and other writings

had made him a celebrity, and after a few years if intense poverty, he lived

comfortably for the rest of his life, though he wandered from city to city

and host to host, and became the ultimate example of the exiled

intellectual.

Dantean scholars have emphasized particular aspects of his

work and influence that make him one of the two or three greatest poets of

all time. C. S. Lewis wrote of Dante’s love poetry being a union of divine

and sensual love, John Freccero offered that Beatrice reconciles human love

with the Divine plan, and Harold Bloom said she is “the allegory of the

fusion of sacred and secular, the union of prophecy and poem.” T. S. Elliott

wrote that Dante’s poetry has “the quality of surprise” that E. A. Poe said

was “essential to poetry,” while Bloom proffered that Dante’s works have “a

strangeness” that we can never completely internalize, and that it is this

that gives his poetry its startling originality. Carlyle simple wrote that

intensity is “the prevailing character of Dante’s genius.” Northrop Frye

suggested that Dante’s Commedia is the supreme example in literature of the

“marvelous journey,” while Erich Auerbach said that Dante’s poetry is

spell-binding, and that readers are charmed into entering a magical world.

Dante’s influence has been immeasurable, largely through the

impact he had on Petrarch, whose sonnets and poems in turn created romantic

poetry as we understand it today. Dante’s philosophy and theology have cast

a giant shadow upon subsequent thinkers, visionaries, churchmen, and

authors. His use of the vernacular Italian, as opposed to the more

acceptable Latin, linguistically changed just about everything. But more

than anything else, it is Dante’s great lyrical power as a poet that gives

him his charm, his darkness, his hope, and his radiance. All of the writers

quoted above touch upon some of the aspects that place Dante’s poetry in a

class by itself. But perhaps Bloom, the most eloquent of Dante’s admirers

after Carlyle and Elliott, summed it up best when he wrote that Beatrice was

“a Christian muse” and that for Dante, “love begins and ends” with her.

For Dante’s greatest works,

The Commedia and

La Vita Nuova, are first and

foremost poems about love, and Dante is primarily a poet/prophet of love,

whether earthly or spiritual, whether of the flesh or of the soul. No one

wrote anything like he did before he lived, and no one has come close to his

daring or his depth since he died. When one considers that the girl Dante

loved only uttered a handful of words to him during their lives, it is

almost impossible for us to comprehend that with words alone, he created a

poetic vision so unique and so influential that it is best summed up with

the one word he made synonymous not only with himself, but with Love itself.

That word is simply the name of the Muse who made him happy and who led him

beyond himself even after her death and his exile from Florence: Beatrice.

Without Dante’s vision of Beatrice, Love as we understand it today – if we

can be said to understand it at all – would be but a shadow of itself, and

we would be immeasurably poorer both philosophically and poetically for this

loss. Bless Beatrice! Bless Dante! And bless all those who risk their hearts

in the great adventure known as Love.

Her color is

the pallor of the pearl,

A paleness perfect for a gracious lady;

She is the best that Nature can achieve

And by her mold all beauty tests itself;

Her eyes, wherever she may choose to look,

Send forth their spirits radiant with love

To strike the eyes of anyone they meet,

And penetrate until they find the heart.

You will see Love depicted on her face,

There where no one dares hold his gaze for long.

Dante,

an excerpt from the poem “Ladies who have intelligence of love” in

La Vita Nuova (The

New Life), circa A.D. 1295, translated by Mark Musa, 1973

Categories:

Literature

|

Tags:

Beatrice,

Commedia,

Dante,

dolce stil nuovo,

La Vita Nuova,

William Blake |

Posted on

July 7, 2013

by

shammock2012

Pusey House is a very special chapel that shares facilities

with St. Cross College at the University of Oxford. Established in 1884 in

honor of one of the founders of the Oxford Movement, which sought to return

the Anglican Church to the more formal service of the early days of the

English Reformation – before the rise of the Puritans – it was named for Dr.

Edward B. Pusey (1800-1882), who took up the mantle of leadership of the

Anglo-Catholic tradition within the Church of England after John Henry

Newman converted to Catholicism. Pusey House Library comprises Pusey’s own

vast library and many other books acquired or donated since Pusey’s death.

The service is beautiful and traditional, with Solemn High

Mass on Sunday mornings that some would say is more Catholic than Catholic,

something which has surprised even those familiar with the modern Anglican

church, including a friend with whom I attended. The sermons/homilies are

engaging and quite often penetratingly witty and apropos, as befits the

grandeur of this old university city. But I must say that the music is the

part that is truly ethereal and hauntingly beautiful, and the small ensemble

making up Pusey House Choir fill the chapel with the sounds of Byrd, Tallis,

Mozart, Vaughn Williams and others every week during term time. Even those

familiar with the masses of these composers receive a chill upon hearing

such sounds during the solemnity of a High Mass, in the midst of the “smells

and bells” of the Anglo-Catholic rite. Simply put – I have never heard such

singing and pipe organ playing in a church of this size, and only very

rarely in the greatest cathedrals. Ironically, perhaps only the word “magic”

can possibly describe the hard work and pain-staking practice that

inevitably results in such spine-tingling sacred song.

After each Sunday morning mass a reception is held where

juice, wine, and sometimes champagne are served and where visitors and

members can meet the priests, sacristan, and the Friends of Pusey House.

There are also periodic suppers and dinners within the House and the

priests, who are fellows of St. Cross College, can often be seen and met

whilst entertaining their guests at various St. Cross dinners.

As the sacristan’s emails say to the elect, as those simply

on the email list may be called, it truly is beautiful and intelligent

religion!

“I was glad when they said unto me, let us go into the house

of the Lord….”

King David of Israel,

Psalm 122, ca. 1000 B.C.

(King James Version, A.D. 1611) (This psalm has been set to music several

times and is traditionally sung during the coronation of British monarchs)

Categories:

Churches

|

Tags:

Choir of Pusey House,

Dr. Edward B. Pusey,

Oxford Movement,

Pusey House Chapel,

Solemn High Mass,

St. Cross College,

University of Oxford |

Posted on

June 10, 2013

by

shammock2012

Last summer I took a trip to visit a friend on one of

Georgia’s Golden Isles to record archaeological sites. Little Cumberland

Island (LCI) is a private island owned by an association of homeowners, so

it was a wonderful privilege to be invited there at all! The purpose was to

record the coordinates of a few surface scatters of artifacts that had

become exposed by waves and wind on the beach and in the sand dunes.

After crossing over from Jekyll Island by boat and a lovely

evening with my hosts, we started bright and early on our peregrinations, as

we knew the day would be hot. There was still no way to imagine just how

hot! It felt like 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, with 100% humidity,

by eleven o’clock in the morning! But we pushed on through, and visited

several sites including a couple Archaic period shell middens, a prehistoric

ceramic-making site, a Union sailor’s relocated grave, and the lovely tabby

lighthouse.

An Archaic Shell-Midden

on LCI

LCI Lighthouse

It was a unique experience that I hope to repeat some day,

and I am indebted to my hosts for their hospitality and the opportunity to

visit a special place that even most Georgians never see. And we even got to

see the wild horses on the beach!

LCI’s Wild Horses

“The sun was

shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright….”

Lewis

Carroll,

The Walrus and the Carpenter,

1872

Categories:

Archaeology,

Exploration

|

Tags:

archaeology,

Georgia,

Jekyll Island,

Little Cumberland Island |

Posted on

June 6, 2013

by

shammock2012

Two of us ramblers recently took a walk up Jericho way

looking for a hidden cemetery called St. Sepulchre’s, a Victorian graveyard

on the site of an old farm. Despite containing still more examples of

vandalism and neglect amongst Oxford cemeteries, as well as a great many

graves completely overgrown with grass and briers, it was a beautiful spring

day and we were able to take some charming photographs of the scene and

setting. Quite a few leading Oxonians, masters of colleges, and mayors are

interred at St. Sepulchre’s, the most famous probably being Benjamin Jowett,

Master of Balliol College and arguably the most famous translator of Plato’s

dialogues and other classical works into English.

Grave of Benjamin

Jowett

Additionally, a highly interesting group of stones mark the

places where the Sisters of the Society of the Holy and Undivided Trinity

(commonly called Sisters of Mercy) were laid to rest. These Anglican nuns

had deep-rooted connections to the Reverend Dr. E. B. Pusey and the Oxford

Movement, and were led by Mother Superior Marian Rebecca Hughes – the first

woman to take vows as an Anglican nun since Henry VIII’s dissolution of the

monasteries during the English Reformation. Interestingly, Mother Marian was

also the sister of Thomas Hughes, the author of the classic Victorian school

boy novel Tom Brown’s School Days.

Grave of Eight Year Old John Henry Silliman

Ah – the gems

of largely forgotten places and memorials to our predecessors that exist in

“this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England!”

“…either death is a state of nothingness and utter

unconsciousness, or, as men say, there is a change and migration of the soul

from this world to another. Now if you suppose that there is no

consciousness, but a sleep like the sleep of him who is undisturbed even by

the sight of dreams, death will be an unspeakable gain….Now if death is like

this, I say that to die is gain; for eternity is then only a single night.

But if death is the journey to another place, and there, as men say, all the

dead are, what good, O my friends and judges, can be greater than this?…What

would not a man give if he might converse with Orpheus and Musaeus and

Hesiod and Homer? Nay, if this be true, let me die again and again.”

Plato,

Apology, Socrates’ Last

Words, ca. 399 B.C.

Translated by

Benjamin Jowett, 1871

Categories:

Cemeteries,

Exploration,

Literature

|

Tags:

cemetery,

Jowett,

Mother Marian,

Pusey,

St. Sepulchre's,

Thomas Hughes,

Tom Brown |

Posted on

May 30, 2013

by

shammock2012

The reconstructed Globe Theatre is a magical place! Although

it does not sit on the exact location of the original, Elizabethan

construction techniques and architectural details were researched and

followed as closely as possible. Ironically, this new vessel for presenting

the plays of Shakespeare’s genius and those of his brilliant contemporaries

like Marlowe, Beaumont & Fletcher, Jonson, Middleton, Kyd, and the rest was

the vision of American actor Sam Wanamaker. Based on contemporary drawings

and descriptions of Elizabethan theatres like the Swan, and on modern

archaeological investigations of the Rose and original Globe, the new Globe,

which opened in 1997, is truly a beautiful work of architecture.

And to watch a Shakespearean play performed there, as I did

recently, is an enthralling and mystical experience. For despite the

Oxfordians and others who crop up like termites from time to time insisting

that Shakespeare did not write Shakespeare because he was not educated well

enough and came from the lower middle classes, it is abundantly clear to

anyone with less than half a brain that the glover’s son from smalltown

Stratford-upon-Avon, through the hard work of his hands and an explosion of

creativity in his mind, is indeed the playwright of

Hamlet,

Macbeth, and the rest.

The Tempest

was on the night a friend and I were in attendance at this new “wooden O”

after a wonderful day in London visiting various landmarks. It was

authentically enacted in Elizabethan garb, and performed so well that it

brought out ideas that had not occurred to me merely by reading this play of

magic and illusion numerous times. The actors were surely, to paraphrase

Shakespeare’s friend, rival, and inspiration Chrisopher Marlowe, “no spirits

but the true substantial bodies” of Prospero, Miranda, Ariel, Trinculo, and

the rest, until the spell was broken and the magic scene disappeared from

the stage forever – except perhaps in the minds of the playgoers!

“Our revels now

are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.”

William

Shakespeare,

The Tempest, 1611

Categories:

Archaeology,

Literature,

Theatre

|

Tags:

Globe,

Marlowe,

Oxfordians,

Prospero,

Shakespeare,

The Tempest |

Posted on

March 30, 2013

by

shammock2012

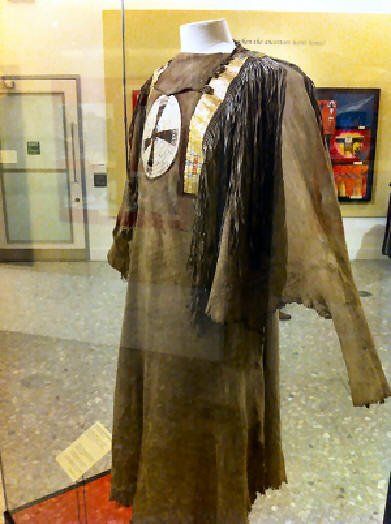

This is an amazing new exhibit in England that I just

happened to walk by when I was at the Pitt Rivers recently. These shirts

date to around 1850, when they were given to British officials operating

near the U.S.-Canadian border (Montana/Alberta), and they eventually found

their way across the pond. The Blackfoot themselves seem to have had no

knowledge of them until a few years ago, when some dignitaries were invited

to inspect them and help contextualize them for the museum. It was

immediately apparent that these were sacred items that should be shown to

the Blackfoot people at large, so the five shirts (three of which are

currently on display in Oxford) were loaned out to local museums in the U.S.

and Canada so this could happen. The impact was tremendous, as Blackfoot

men, women, and children responded powerfully to these shirt their ancestors

had made by hand and generously given away. It was another outstanding

example of Native American heritage abroad that I have been overjoyed to run

across thousands of miles from home here in the UK!

Blackfoot Shirt

Side of Shirt

Shirt Detail

showing bows and musket

Painting Depicting

One Shirt

Blackfoot Shirt

“A little while

and I will be gone from among you, when I cannot tell. From nowhere we came,

into nowhere we go. What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night.

It is the breath of a buffalo in the wintertime. It is the little shadow

which runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset.”

Chief

Crowfoot of the Blackfoot,

Deathbed Speech, 1890

Categories:

Archaeology,

Museums

|

Tags:

Blackfoot Indians,

Blackfoot Shirts,

Crowfoot,

Native American,

Pitt Rivers |

Posted on

March 26, 2013

by

shammock2012

Exploring cemeteries has long been a favorite pasttime.

Recently I chose a blustery wintry day in early Spring to walk to Wolvercote

Cemetery, north of Oxford, to visit the grave of one of the greatest

imaginative storytellers of the 20th century – J. R. R. Tolkien. I savour

these moments so much, however, that I only went to his grave after

exploring the rest of the cemetery for over an hour, building up the

suspense! Seeing the graves of children along the way, decorated with their

toys and cards from their parents, is always so touching. I cannot fathom

the sadness those families must have felt and will always feel. Oxford

scholars, priests, rabbis, mothers, and fathers – all are represented at

Wolvercote. Even a minister from Kentucky with a Cherokee motto on his

tombstone! The grave of Tolkien and his wife was worth the wait –

especially because of the copies of his books and notes and tokens left by

his readers. Such an ordinary British grave in an ordinary British

cemetery. That speaks volumes.

Another thing has struck me about Oxford’s cemeteries, and it

is not at all positive. There are far too many vandalized graves here for

such an affluent community. Rose Hill Cemetery, just east of Oxford, is no

different. What possesses the living to destroy the houses of the dead? I

have long been a believer that the callousness of those who would destroy

graves for no reason is not far removed from the hatred and reckless

destruction that causes others to take the lives of of living human beings

for no reason.

“All we have to

decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

“Not all those

who wander are lost.”

“It’s a dangerous business…going out your door….You step onto

the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you

might be swept off to.”

J. R.

R. Tolkien,

The Fellowship of the Ring,

1954

Categories:

Cemeteries,

Exploration,

Literature

|

Tags:

Cemeteries,

graves,

Oxford,

Tolkien,

Wolvercote |

Posted on

March 24, 2013

by

shammock2012

Exploring the Ocmulgee, Oconee, and Flint Rivers of Middle

Georgia is not for the faint of heart, but for the adventurer! Whether by

kayak, canoe, or motor boat, by foot on trails or along densely wooded banks

where no path has been trodden, in the water with a mask and snorkel or

SCUBA gear, or in the sky by helicopter or plane, there are many ways of

looking for long lost traces of Native American dwellings, mounds, fishing

weirs, and towns, and for the forts of the soldiers and homes and ferries of

the early settlers who followed in their wake. The most important aspects

are obtaining the landowner’s permission and knowing someone on the ground

in any given locale. This person is the key to the success of any explorer,

and it is they who serve as escort and guide through the snares and tangles

not just of briars and brambles, but of local indifference or

misapprehension. When it becomes clear that knowledge and the subsequent

enrichment of the community are the ONLY goals, then most are interested in

helping sooner or later.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would

appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he

sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.”

William

Blake,

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,

1790

Categories:

Archaeology,

Exploration,

Literature

|

Tags:

doors of perception,

Flint,

Kayak,

Ocmulgee,

Oconee,

River,

William Blake |

Posted on

March 20, 2013

by

shammock2012

“There is scarcely a square rod of sand exposed, in this

neighborhood, but you may find on it the stone arrowheads of an extinct race

that has preceded us….Time will soon destroy the works of famous painters

and sculptors but not the Indian arrowhead….They are not fossil bones but

fossil thoughts, forever reminding me of the mind that shaped them….I know

the subtle spirits that made them are not far off, into whatever form

transmuted….Originally winged for but a short flight,….it still wings its

way through the ages….bearing a message from the hand that shot it. Myriads

of arrow-points lie sleeping in the skin of the revolving earth, while

meteors revolve in space….The footprint, the mind-prints of the oldest men.”

Henry David Thoreau,

Journals, 1859

Categories:

Archaeology,

Literature

|

Tags:

arrowhead,

Clovis point,

Georgia,

Henry David Thoreau,

Jones County |

|