|

One of the great pleasures of being a bibliophile, or

lover of books, is discovering a rare but enjoyable one written long ago.

This particular book, Benjamin Franklin in Scotland and Ireland, 1759

and 1771, was written by J. Bennett Nolan in 1938, the year of my

birth, and has a special attraction to me. You see, I never knew of Benjamin

Franklin’s two tours of Scotland nor of his love of our auld country and its

people. Ben had many Scottish friends in Philadelphia, and he actually

“assisted in the outing of the St. Andrews Society of Philadelphia and

joined in singing ‘The Bonnie Braes of Balwither’.” And it is

recorded that he attended the Burns Night Supper at the St. Andrews Society

there in 1762.

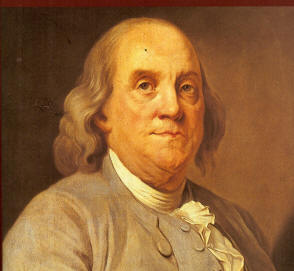

Benjamin Franklin

Susan and I took a trip a few years back in search of

information on two authors - Benjamin Franklin and Ernest Hemingway. Reading

Walter Isaacson’s most incredible book, Benjamin Franklin, An American

Life, brought the former kite flyer back into my life in a big way.

How can you not like a fellow who could write one liners such as “three may

keep a secret, if two of them are dead”? I knew I would be headed back to

Scotland sooner or later and felt a trip to Paris and London would be great

extensions of that trip.

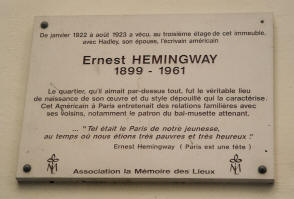

Both photos are taken at the location of

Hemingway's first apartment in Paris. The left photo is a historical marker

placed by the French government and the one on the right shows the front

door.

I made notes to find the Franklin house, as well as the

statue of the great scientist, in the Passy suburb of Paris. Later I dug

through books to find the haunts of another hero - big, bad Ernest

Hemingway. So, in 2005, a trip to Scotland found us attending the Robert

Burns World Federation meeting in Ayr, then taking a quick flight on British

Airways from Manchester over to Paris, and finally back across the English

Channel to London on another BA flight. What a great time!

Paris meant a visit with Catherine LeGuay, our good

Parisian friend from Susan’s days as corporate secretary of The Coca-Cola

Company. Catherine now operates a great little bed-and-breakfast at 16, rue

Linne in the heart of Paris. Check it out! Paris is one of life’s top

experiences, and it afforded us the chance to engage Hemingway, walk where

he walked, eat in a few of his favorite restaurants and cafes, devour a

hotdog at Harry’s New York Bar, birthplace of the Bloody Mary and “where

drinks don’t come with paper umbrellas”, visit the Catholic Church of Passy

where he married Pauline, and raise a glass or two of wine to him…each meal,

each day! Ernie would have been proud!

The famous Brasserie Lipp which was a hangout of

Hemingway when he had money.

In our search for the Franklin house and statue, I don’t

believe I have ever walked in loafers so far in the course of a day in

either Europe or America, and the evening found me soaking my tired flat

feet in the hotel bathroom. Lord, did they ache!

On, now, to Franklin’s Craven Street home in London, the

world’s greatest city at that time. He lived here for nearly 16 years over

two different assignments or tours of duty from 1757 until 1775. The first

tour was from 1757 through 1761. He returned for a round in 1764 for 11 more

years. Both times he lived in the same house that today is 36 Craven Street,

a five-minute walk from Trafalgar Square, and only a few minutes from

Whitehall, the seat of England’s government. Actually, Franklin spent the

majority of the last 33 years of his life residing outside the USA.

So on that typical English day, cold and rainy, we made

our way with map in hand to Franklin’s home in this appealing city that I

love to visit. Yes, we walked but this time with walking shoes purchased the

day before at Harrods. Unfortunately Franklin’s house was closed for

conversion into a museum. But, hark, the herald angels do sing since a few

doors down a reception was being held that afternoon at an optical society

suite of offices where several Franklin items were on display - some bronze

busts, plus a pair of bifocal glasses reputed to have been made by the great

inventor at his London home.

That Sunday afternoon at Trafalgar Square, Susan and I

stood like the tourists we were watching Prince Charles and Camilla pass by

with their security motorcycle escort, sirens blaring at full volume.

Neither returned my wave! But the crowd squealed with delight and an

audible buzz erupted as they passed.

Prince Charles and Camilla

I’ll take Susan back to the Franklin house another day to

visit the wonderful old dwelling that is now a functioning museum, study

centre, and the only surviving house, including those in Philadelphia, where

Franklin lived. In the meantime, I now receive the newsletter from the

Craven Street museum to keep updated.

Now hear this! From the heart of London, if you can

believe it, came a message from across the pond this past spring inviting me

to “celebrate the 4th of July at the Benjamin Franklin

House, Wednesday, 4 July 2007. Stop by for Cake and Bubbly”. A

pencil print of Franklin’s house was included in the email along with a red,

white and blue picture of Old Glory! I couldn’t help but chuckle! The $16

ticket did not matter. The Brits were honoring a man who was a most stubborn

thorn in their side before, during, and after the War of Independence. By

the way, if you are interested in receiving the newsletter from time to

time, contact the powers that be at the Benjamin Franklin House at

info@benjaminfranklinhouse.org.

Finally, we get to the book in question and a word about

the author. Nolan’s books are still in demand today. He has written on many

subjects, including George Washington. While searching through the many

pages on Google about our writer, I found one of his books currently for

sale to the tune of $175. He must still be relevant!

Naturally, this review will not be followed by a “Chat

with the Author” as in the case of my previous ones since this is the first

time I have reviewed a book so old, but I do offer a tip of the hat to the

deceased author, J. Bennett Nolan, for a book well written and a raised

glass in his honor as well!

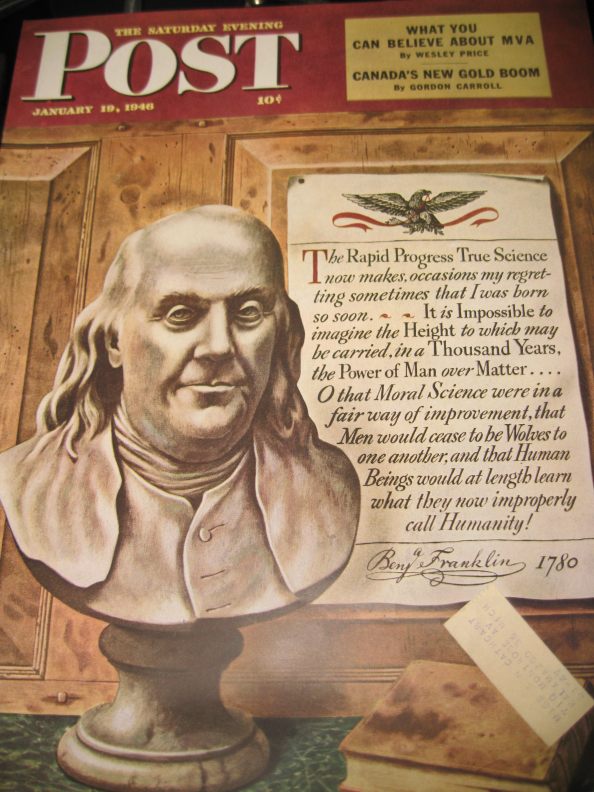

Franklin before the Privy Council in 1774 in

London. Many think that this was the turning point when Franklin became a

devout patriot for America, forsaking his loyalty to England and the King.

________________________________________________________________________

Benjamin Franklin in Scotland and Ireland 1759 and 1771

By J. Bennett Nolan

Reviewed by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA,

USA. Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

This wealthy man, who is known to many of us today as

Poor Richard, lived in the home of a refined widow, not a boarding house as

some have written. During his time in London, Franklin decided to go north

on vacation and accept the invitation extended to him and his son, William,

by Lord Kames. Unlike his father, William remained loyal to the King after

the outbreak of the War of Independence. He also served as Governor of New

Jersey but split with his father over political views and was eventually

arrested, spending two-and-a-half years in a Connecticut prison.

Franklin had many friends in Scotland, mostly

philosophers, professors, and men of science. He received several honors

while in Scotland, including a Doctor of Laws from the University of St.

Andrews. The Rector who presided at the ceremony was Dr. David Shaw, and

Franklin, impressed by the good Rector, said “I took much to Shaw.” He was

made a Guild Brother of Edinburgh, a city of 50,000 people, which was just

beginning to be called “The Athens of the North”. Then there was “the

elevation of Benjamin Franklin as a Guild Brother of the town of St.

Andrews”. He was feted wherever he went in Scotland and lived up to his

reputation of a two-bottle man.

The defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie had occurred a mere

14 years before Franklin’s visit, and it was also just before Scotland’s two

greatest writers burst on the scene - Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott. Yet

Franklin recorded little about his visit to Edinburgh or Scotland. Only half

a dozen letters have been found about his time in Scotland. Henry Stevens,

the great collector of Frankliniana, simply said that Franklin “was too busy

in making history…to sit down quietly to record it”.

One of his forays into the countryside found Ben at the

new Carron Iron Works, emblematic of an industrialized Scotland being born.

Franklin was particularly interested in this company because they

manufactured one of his inventions, helping to make him a wealthy man. One

Carron advertisement read, “Made on the model of Dr. Franklyn’s Philadelphia

stove.” Remember this company’s name for it played a small chapter later in

the life of Robert Burns.

The Second Trip to Scotland

In 1771, the 66-year-old Franklin made his way north

again but this time by way of Ireland. The years were beginning to take a

toll on the old philosopher. He was not as active or alert. His eyesight was

beginning to diminish. His body was showing the effects of old age, yet he

was to live another 19 years - eventful ones I might add.

Benjamin Franklin still remained a loyal subject of King

George. He loved England and he loved Scotland. He loved their people. The

last thing in his mind was breaking away from all that he loved about

England and working to establish a country called America.

The author writes in 1938 about Stirling Castle saying,

“The place has changed little since Franklin’s day but, of the thousands of

American tourists who annually scramble over these same walls and admire the

prospect of the Highland hills above the winding links of Forth, very few

ever pause to think of Poor Richard puffing and panting along Stirling’s

ramparts in 1771”.

Another incident recorded by the author is worthy of our

attention. On a walk from Edinburgh University where Franklin had met with

his old friends Doctors Cullen, Black, and Munro, the author describes a

scene about Franklin:

“As he passed down the narrow

College Wynd he could have noticed at the window of the second story a short

swarthy woman holding an infant boy then eight weeks old. The house was that

of Walter Scott, Writer to the Signet, the woman was his wife, Ann

Rutherford, and the baby was another Walter Scott whose fame was to ring

down the ages with as much insistence as that of Poor Richard

himself.”

Franklin’s traveling companion on this trip was Henry

Marchant, Attorney General of Rhode Island who, thankfully, describes in his

diary the events they shared in Edinburgh. One such diary notation was about

the few hours of daylight available. “Novr. 8th The Morning is

most delightful. We took a Walk of 9 or 10 miles round & returned with a

good appetite to an elegant Dinner. In Short - The Days are now so short

that scarce anything can be done but eating, drinking & sleeping. The sun

rising 32 minutes after 7 and setting 52 Minutes after 3 o’clock.”

On the way back to London, Franklin made a point of going

to Preston to meet the family of his son-in-law. He was greeted by Mrs. Mary

Bache, the mother of twenty children. Ironically, because of his eleven-year

assignment in London, Franklin had never met his son-in-law, Richard Bache.

The family was delighted by the visit of this world renowned man, and they

were particularly impressed by his affability and simplicity. He later sent

the Bache family a portrait of himself.

Upon his return to London he wrote, “My last expedition

convinc’d me that I grow too old for Rambling…the Parting with friends one

hardly expects ever again to see.”

In Conclusion :

Bits and Pieces

British General John Burgoyne, the representative in

Parliament for Preston, is the same General Burgoyne who surrendered at

Saratoga, New York, preventing the British from dividing New England from

the rest of the colonies. After the war, some members of the Continental

Congress wanted General Burgoyne brought back to America as they maintained

he was still a prisoner of war. Franklin, serving in Paris at this time and

perhaps remembering the good people and the good times of Preston, would

have none of it and helped secure Burgoyne a parole.

Franklin once said, “For my own part I find I love

company, chat, a laugh, a glass, even a song, as well as ever”. And, at the

end of the day, he would take cap and cane, head for the Temple Bar “on the

top of which were still impaled the skulls of the gallant Jacobites who had

paid the forfeit of their support of the forlorn hope of the unhappy Prince

Charlie”.

Franklin and Edinburgh printer William Strahan had

corresponded for over 20 years. They had bonded during their meetings in

Scotland and also when Strahan visited Franklin in London while serving as a

Member of Parliament. The American Revolution had caused a big riff in their

relationship, and Franklin wrote a letter to Strahan saying, “Look to your

hands, they are stained with the blood of your relations. You and I were

long friends. You are now my enemy, and I am yours…” Yet, when Franklin was

serving as America’s diplomatic agent in France, “the unperturbed printer

sent over to Paris a present of Stilton cheese…” for Franklin’s enjoyment.

Some say Franklin wrote the letter but never mailed it.

For the many Scottish lovers among us, “Sally Franklin in

Philadelphia received a collection of Scots songs from Lady Dick”, a close

friend of Franklin’s in Scotland which shows another connection to Ben’s

relationship to Scots”. Sally is Ben’s daughter who married Richard Bache,

and the couple named their son Benjamin Franklin Bache.

Though he was accused of irregularity in religion, we

find Franklin “involved in the negotiations which led to the election of the

Reverend John Witherspoon of Paisley as President of the College of New

Jersey at Princeton”. When a young Billy Patterson, future Associate Justice

of the Supreme Court, heard of the appointment, he wrote to a friend,

“Witherspoon is President. Mercy on me! We shall be overtaken with

Scotchmen, the worst vermin under heaven”. Little did Franklin or

Witherspoon know they would both be signers of the Declaration of

Independence.

As a final quote regarding Scotland, Franklin paid the

country one of its greatest tributes in a letter to Lord Kames, “If

strong connections did not draw me elsewhere, Scotland would be the country

I would choose in which to spend the remainder of my days.” (FRS:

1.16.08) |