|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

This is an extremely welcomed article to the

pages of Robert Burns Lives! by one who has contributed articles over

the years – Kirsteen McCue, professor at University of Glasgow. She is

both a friend and scholar. I met Kirsteen when she was studying at the

Ross Roy summer program at the University of South Carolina. She has

been the guest in our home as we have been with her, her husband David

and her children Dora and Gregor many times in Glasgow. She has many

talents, and among them is that of a wonderful cook of great meals in

her home! As I write this, I am nearing another meal time and wishing

Susan and I were in Glasgow to share another of her meals with her

family, including her delightful mother who lives a couple of doors from

them. It is a home of welcome, warmth, fun and joy. The meal – none

better! The fellowship – the same! Come back to visit again, Kirsteen,

you are missed! (5.31.18)

The Agnes Burns Song Book

By Kirsteen McCue

In January 2017 the Centre for Robert Burns

Studies at the University of Glasgow was given the wonderful gift of a

personal bound music book belonging to an ‘Agnes Burns’ (https://www.gla.ac.uk/news/headline_510155_en.html)

. It was generously donated to the CRBS by George Walker. The story of

the discovery of this intriguing book is recounted for Robert Burns

Lives! by Sally Evans of the Kings Bookshop in Callander in the

Trossachs. While there is still work to be done, the Shaw Summer

Scholarship at CRBS in 2017 made it possible for Dr Brianna

Robertson-Kirkland to undertake some preliminary work on this

fascinating gift. Her findings are presented here for the first time.

Professor Kirsteen McCue: Co-Director of the

Centre for Robert Burns Studies, University of Glasgow

The Agnes Burns Song Book: by Sally Evans (Kings Bookshop, Callander)

Found at a Haddington auction in 1995,

curated by Old Grindles Bookshop, Edinburgh, which became Kings Bookshop

Callander, until 2016, this book was then purchased by George Walker of

Paisley and presented to the Centre for Robert Burns Studies, in memory

of his wife Margaret Bonnar Walker, neé Russell, in January 2017.

This book first came to light at a Lane Sale or “roup” in Haddington in

March, 1995, where it was purchased by Sally Evans for Old Grindles

Bookshop, Edinburgh. Until the end of the twentieth century, auctions

frequently held these secondary sales outdoors in the streets beside

their premises.

We were buying books at auction at a great rate in those years, and

Haddington was one of our handier out-of-town hunting grounds. I’d

driven there to suss out a lane sale, and among other items strewn on

the cobbles and tables I saw a packet of music, including this book. Ian

King, my husband and bookselling partner, likes early Scottish music so

I determined to get it for him, and I saw off a few other bidders for, I

think, £40. At lane sales there were normally no receipts: a clerk

collected the money in a satchel.

Back in Edinburgh, Ian King was extremely impressed by my purchase. He

knew enough about Burns to recognise the Haddington connection, and he

went through the book with the proverbial toothcomb. ‘Well done, Sally’,

he said. The book went into his special safe reserve. We then looked up

the current sales in the Haddington auction house and attended the next

one, where Ian bought all the books in the sale in case there was

anything else connected with it. We found no clues, but the receipt for

£448 for those books is our only document connected with the purchase.

The book stayed in the shop’s reserve, and

in 2000 moved with us and all our possessions to the newly opened

bookshop in Callander. There it remained, shown once or twice to Burns

scholars or collectors, without anyone wanting it enough, or knowing

enough about it, to wish to purchase it, until Professor Nigel Leask (Regius

Professor of English at the University of Glasgow) was in the bookshop

one morning in August 2015, as was, by chance, Professor Murdo Macdonald

of the University of Dundee. Bookshop gossip turned to Burns, and Ian

King said he had a special item upstairs. It was fetched down and

reverently inspected, with much interest from the professors. Professor

Leask took a few photographs, particularly of the flyleaf inscription

and of the mathematical calculation on one of the pages. Could this be

the hand of Burns?

The CRBS expressed interest in acquiring it but were unable to procure

the funds. Here I may point out that a working bookshop needs to sell

its more valuable items; it cannot give such items away, because these

are our stock in trade. Bookshops, like other businesses, cannot survive

on thin air. So, the book remained in our secure store, unsold, but we

now had a potential home for it.

In July 2016, George Walker and I were

travelling in a car together on poetry business. George had been telling

me something of his late wife Margaret, and then, as we were near

Paisley, we got talking about Tannahill and Burns. Entirely without any

intention of pitching our Burns book to him, I started to talk about the

book and the fact that it needed a good home, and the recent interest of

the CRBS at Glasgow University.

George had an idea. ‘Suppose I bought it’, he said, ‘and presented it to

them in memory of Margaret?’. He’d been wondering about possible

memorials to her. I was surprised and impressed. ‘You could come over

and see it, and see what you think and what Ian thinks’, I said. So,

George thought it over, and that was what happened.

And so it has come to the CRBS, George Walker purchasing it from Kings

Bookshop Callander and presenting it to the Centre. Because George and

his two brothers are graduates of the University of Glasgow, he felt

this was particularly appropriate.

Among the strands, this is a story of how a Scottish Antiquarian

Bookshop found and rescued an important Burns document and found the

right buyer and the right home for it, which is the true objective of

second-hand bookselling. And of how a Glasgow graduate found the right

memorial for his dearly loved wife.

Understanding the Agnes Burns 1801 Music

Book: by Dr Brianna E Robertson-Kirkland (University of Glasgow)

This curious composite music collection

consists of 70 print sheet music items and while I spent a lot of time

carefully recording and cataloguing each item, as well as finding

bibliographical information that enables a richer conversation about the

taste, style and performance abilities of Miss Agnes Burns, the volume

presents deeper considerations centring on its construction and

functionality. In this short piece, I would like to reflect on the work

I carried out on this Agnes Burns 1801 composite music collection and

the ongoing questions it has presented.

Composite music collections are not unusual. These personal volumes were

typically curated by young, musically educated women who would purchase

single sheets from local music book shops. Binding the music into

leather volumes was a practical space saver, but also ensured limited

damage was done to the delicate single sheets. In this respect Agnes’s

collection is fairly typical for the period (see

Jeanice Brooke’s detailed work on Jane Austen’s family music

collections). What is unusual however, are the delicate hand-sewn

repairs on a few of the pages. These are not characteristic of auction

house or book-seller repairs (and there are plenty examples of these

throughout the volume), demonstrating a collaboration of feminine

attributes. Polite society ladies were expected to develop beyond their

general education, becoming accomplished in ‘the ornaments’, which

included music, sewing, dance and drawing. The delicate stitching hints

towards Agnes’s social standing, but also raises questions about her

emotional attachment to the volume.

Figure 1: Hand-stitching, bottom right-hand corner. By permission of

University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections

Figure 2: Delicate hand-stitched repairs. By permission of University of

Glasgow Library, Special Collections

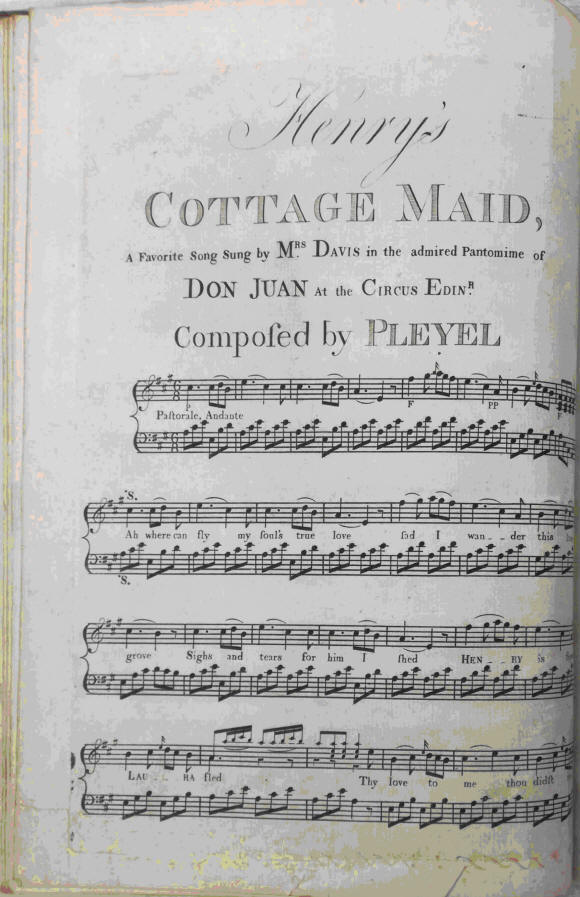

The music contained within the volume is a

mixture of popular theatre songs including ‘The Lullaby’ from Stephen

Storace’s The Pirate (1792), ‘A Jolly Young Waterman’ from Charles

Dibdin’s The Waterman (1774), and ‘When the Hollow Drum’ form The

Mountaineers by Charles Arnold (1793). There are also popular Scots song

such as, ‘Auld Robin Grey’, ‘Lass gun ye lo'e me, tell me now’, and a

duet arrangement of the ‘Caledonian Hunt’s Delight’ (well-known now as

the tune for Robert Burns’s ‘Ye banks and braes’). But one of the most

curious items comprises about half of another volume entirely, namely

the second half of Robert Bremner’s Thirty Scots Songs for a Voice and

Harpsichord […] The Words from Allen [sic] Ramsay bound into the back of

the collection. Because the title page was missing it took me some time

to identify this. What I discovered was that the date of this

publication sits apart from most of the other items in the Song Book.

Though Robert Bremner (c.1713-1789) first published his Thirty Songs in

1757 it appeared in several editions before 1780. By comparing different

editions housed in the University of Glasgow Special Collections and

Archives with Agnes Burns’ copy, I was able to identify that her volume

matched the 1770 edition.

Bremner was a Scottish music publisher, who published music on behalf of

the prestigious Edinburgh Musical Society and acted as an agent for the

Society throughout the 1750s, allowing him to travel to London in search

of the best singers and instrumentalists. By 1762, Bremner’s success as

both a publisher and author of The Rudiments of Music, allowed him to

open a shop on The Strand in London where he continued to publish work

of famous musicians as well as his own music education treatises. Most

of the other pieces appearing in the Agnes Burns Song Book were

published between 1780 and 1800, with only a few items published as

early as 1768 and 1770. While it is possible Agnes accumulated her music

copies over 20-30 years before having them bound in a leather volume, it

is also possible that the volume was a heritage gift, passed down from

another musical family member. Similar examples of these ‘heritage’ song

books can be seen in composite music volumes once owned by Scottish

families who immigrated to

Sydney, Australia in the early nineteenth century. While it is

possible that this is a different family entirely, we do know that

Burns’s mother, sister and niece were all called Agnes, and that his

brother Gilbert and his family moved to East Lothian after 1798-9.

Further work on the possible connection with the poet’s family remains

to be done.

Agnes’s collection contains some of the most popular songs composed and

published at the turn of the nineteenth century. Crazy Jane, a 1796

broadside ballad, which grew in popularity after Rosemund Mountain

performed it at Venanzio Rauzzini’s Bath concert in 1799, appears

alongside several songs by successful songster and theatre composer

Charles Dibdin (1745-1814). Dibdin’s songs are often found in composite

music collections and this demonstrates that Agnes was up-to-date with

current musical trends. However, moving through the volume older and

well-worn song sheets appear including Lango Lee, Jemmy and Nanny sung

by Mrs. Arne at Ranelagh, and Master Brown at Mary-bone Gardens. Lango

Lee stands out because its cheap, thin paper is inconsistent with the

heavier, more expensive quality of the other song sheets. Furthermore,

these older publications tend not to indicate place of publication and

publisher, unlike the contemporary repertoire, which was mainly produced

in Edinburgh, London and Dublin.

While there are no performance markings, there are several incoherent

hand-written notes, including calculations on whaling costs (perhaps in

Robert Burns’ hand), and delicate pen marks, as if a misbehaving child

decided to scrawl over the music. These characterful features enliven

the Song Book, demonstrating that its materiality is just as important

as its content. Some nineteenth century composite music collections

include performance markings, typically illustrating educational use.

For example, a teacher may notate ornamentation, dynamics or even

figure-bass markings to help the student. Agnes’s collection lacks such

insight into her performance practice and does not appear to have been a

musical training tool. However, some sheets are notably better used than

others: The banks of the Tweed: a favourite Scotch song and Dreary dun:

A favourite song sung by Mr. Rider in the Castle of Andalusia are worn

at the corners and have been folded in half prior to binding.

During this period, any young lady from polite society was expected to

have a certain proficiency in music-making, often being called upon to

perform at small gatherings and parties. Such musical activity was

considered safe and a young woman could spend her days playing for her

own pleasure or even for her immediate family members, enlivening the

house with colourful ditties that could only otherwise be heard by

paying to attend performances. Exploring the contents of this Song Book,

one can easily imagine the young Agnes sitting at her forte-piano

playing and singing both old and new hits for her family.

Though we may never be able to identify with certainty Robert Burns’s

hand on the volume, or the exact identity of Agnes, this composite music

collection has inspired me to combine bibliography with an in-depth

reading of the book’s materiality. Song Books like this one are rare.

Exploring such a volume at close quarters helps us form a better

understanding of the motivations of early nineteenth-century female

music collectors and the role of such books in domestic life. They

clearly have value not just as sources of family entertainment, but as

heritage objects to be treasured by generations to come. |