|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

During the mid-1960s, while taking notes in

a senior theology class at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary,

the class was asked to write a minister’s name on a sheet of paper who

we thought was the best Southern Baptist minister in our huge

denomination and to turn it in as we left class for a discussion during

our next session. The professor made no bones about his opinion during

the discussion and explicitly said that it would not be the minister of

one of the larger churches with memberships in the thousands. He felt it

would be the pastor of a small congregation that numbered far less than

that. Needless to say, the class of would-be ministers was dumbfounded.

His explanation was plain and simple as he explained to us that there is

no way a minister, no matter how gifted a speaker, could nurture a

church with such large members. I have changed my mind over the years as

I was for the guy with the large congregation. As I have matured over

the years and have become the owner of facilities caring for the

elderly, one should greatly consider a smaller congregation nurtured by

only one person.

So my question to you is, who is the greatest writer among those who

have shared their work - articles, sermons, notes, or book chapters -

with us over the years in Robert Burns Lives! I will not ask you to send

me their names because I am now older than the professor was at the time

he gave us that very brief assignment, and my mind is prone to wander

from time to time and I will more than likely pick someone before these

eyes shut for good.

I come to today’s guest writer with a lot of enthusiasm because he has

shared with us many times his beliefs regarding many subjects but has

never left us empty hearted. He is, of course, Dr. Patrick Scott,

retired professor at the University of South Carolina who is probably

busier now than when he was teaching. You are really in for a treat with

this article as Patrick shows his talent in the piece of work at hand

today. (FRS 12.14.17)

A Neglected Source for Burns Manuscripts?

Some Old Guides for Autograph Collectors

by

Patrick Scott

So much is known, and published, about Burns

and his manuscripts that it may seem unnecessary to go looking for more.

However, manuscripts that are “known” and have been used by earlier

Burns editors don’t necessarily stay in the same place or ownership

forever, and a surprising number are now referenced as “unlocated.”

Recently, I’ve been exploring Victorian facsimiles as a way of

researching these lost manuscripts. There have been a lot of Burns

facsimiles over the years, sometimes as illustrations in biographies or

editions, sometimes as single pages issued as separate collectible

items, and sometimes in sumptuous full-scale volumes, as with the Geddes

Burns, the Glenriddell Manuscripts, or the First Commonplace Book. The

Roy Collection has a bound volume of Burns facsimiles that Robert

Chambers had used in the 1850s, and it is still possible to pick up sets

of Seymour Eaton’s tartan-bound portfolios of lower-quality Burns

facsimiles and illustrations published in Philadelphia early in the 20th

century. Facsimiles are becoming more collectible, because unframed they

are difficult to store, and even the ones that were in books often get

detached and dog-eared. Some facsimiles are very good: if a past owner

had a facsimile framed for display, it can often be mistaken by hopeful

heirs as the real thing.

One kind of Burns facsimile that flies under the radar is especially

intriguing. In the later 19th and early 20th century, autograph

collectors needed help checking the authenticity of signatures and

manuscript items, and enterprising publishers responded with illustrated

guides to the handwriting of famous people.

Victorians couldn’t go online and check the

authenticity of a stray item against digital images of Burns’s

handwriting. from the National Library of Scotland, the Birthplace

Museum, or Future Museum. The extraordinary success of the forger

Antique Smith in the 1880s shows how even sophisticated, wealthy

collectors and their advisors often lacked the tools to determine

authenticity. The autograph guides discussed here typically cover many

authors, and they don’t get into the standard Burns bibliographies or

catalogues, so hunting them down can be frustrating.

Many of the general guides for autograph collectors include facsimiles

of one or more Burns items, and many of these facsimiles are still

unrecorded. One influential late Victorian guide, Autograph Collecting

(1894), for instance, by the physician-turned-clergyman, Henry Thomas

Scott, has a whole chapter on Antique Smith but frustratingly includes

no facsimile of Burns. However, the same author’s Guide to the collector

of historical documents, literary manuscripts, and autograph letters

(1891) has an unindexed facsimile of Burns, the opening of his letter to

Mrs. Dunlop in March 1789 about returning from Edinburgh to Ellisland,

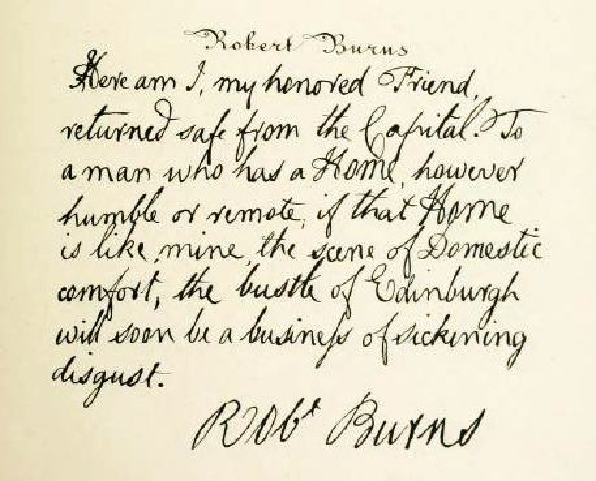

and the importance of having his own home (Letters, I. 381):

Burns to Mrs. Dunlop, March 4, 1789, from

Scott (1891)

The major published autograph guides

typically reproduce the manuscripts of well-known items. For instance,

P.J. Croft’s authoritative modern collection Autograph Poetry in the

English Language (1973) has just one Burns manuscript, the version of

”Auld Lang Syne” from the Interleaved Scots Musical Museum, in the

Birthplace Museum (Croft, vol. I, p. 93). Similarly, one of the

full-scale older sources, George F. Warner’s huge and handsome Universal

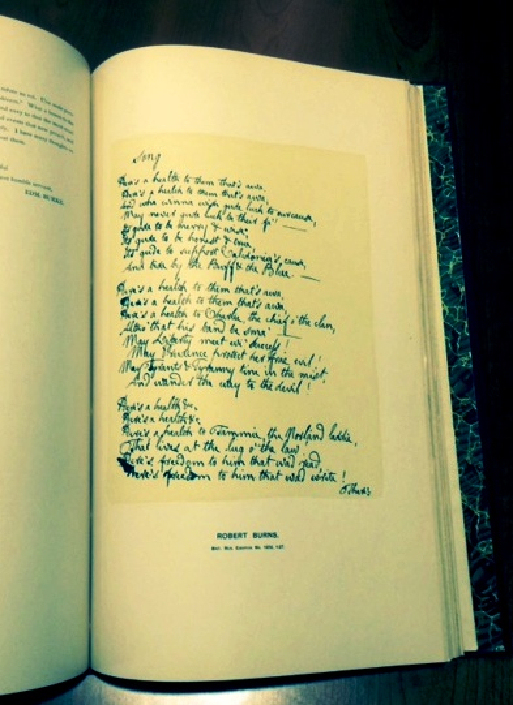

Classic Manuscripts (1901), reproduces the Burns song “Here’s a health

to them that’s awa’” from the Egerton MS. in the British Library.

Warner’s facsimile only gives the first page, and it also omits William

Wallace Currie’s characteristic marginal notations (“Copd” and “C v 2 fo

278”) which show the manuscript had been used for the Currie edition

(cf. Smith, IELM, II:1:127).

Burns, “Here’s a Health to them that’s awa,”

from Warner, Universal Classic Manuscripts (1901)

The skeptical researcher may wonder if

pre-photographic facsimiles are indeed trustworthy. In the letter to Mrs

Dunlop illustrated earlier above (from Scott, 1891), the original

manuscript of the letter survives, safe in the Rosenbach Library in

Philadelphia, and it shows that the lithographer has rearranged the

lines of Burns’s handwriting and has added in the signature from the end

of the letter so it follows the first sentence. The shorter the snippet,

the more likely it is to have been doctored in this way.

The earliest recorded attempt to photograph a poetic manuscript was

probably in 1840, when the pioneer photographer William Fox Talbot

photographed Byron’s “Ode to Napoleon” (Mole, p. 157). An 1869 facsimile

of the Kilmarnock manuscript of “The Lament of Mary, Queen of Scots” was

advertised as produced by “photo-chromolithography.” But most 19th

century facsimiles were produced by drawing or tracing the original onto

a copper plate or a prepared stone surface, which was then engraved by

hand for printing, or drawn onto the stone with crayons for reproduction

by lithography. While the lines in the redrawn facsimile were commonly

less strong or firm that Burns’s penmanship in his heyday, the accuracy

of the copying could be assisted by a “camera lucida” (patented in

1807), where the copyist saw an image of the original on the surface

where he was drawing. Both engraving and lithography required that

illustrations be printed separately from any explanatory text, so page

numbering for facsimiles is often irregular or lacking. (Other

processes, wood-engraving in the earlier period and photogravure, from

the 1870s, could be printed as part of the text.)

Because of such processes, even before photography, the craftsmen who

engraved a facsimile or drew one for a lithograph were generally

accurate about wording and punctuation. Early facsimiles can in fact be

very useful in researching Burns’s text. While the shaky lettering of a

careful or nervous copyist did not always look convincingly like Burns’s

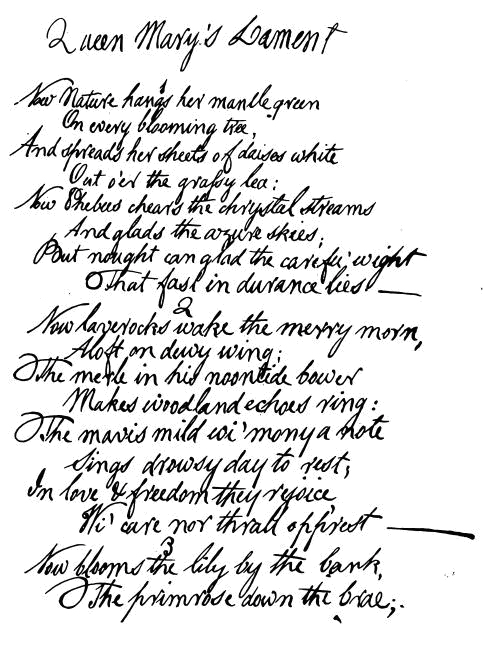

confident hand, the details often prove to be exact. An example is the

facsimile of “Queen Mary’s Lament” in Charles J. Smith’s Historical and

Literary Curiosities Consisting of Facsimiles of Original Documents,

which came out in parts in 1835-1840, and was then published as a

collection in 1847, 1852, and 1875.

Burns, “Lament of Mary, Queen of Scots,”

from Smith, Historical and Literary Curiosities (1875)

The question is which manuscript of the poem

Smith was reproducing. Smith had engraved the facsimiles himself, and

his contents list indicates that it came “From Mr. Upcott’s Collection.”

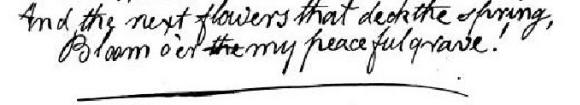

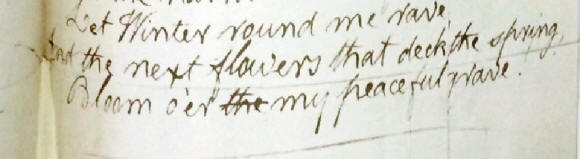

The very last line of Smith’s facsimile, “Bloom o’er my peaceful grave,”

records a variant where Burns changed his mind about a word, first

writing “the” and then crossing it out and writing “my.”

The last lines of “Lament of Mary, Queen of

Scots,” from Smith (1875)

This variant occurs in just one of the known

manuscripts, variously called “Bixby B,” after its owner in the early

20th century, and “Huntington,” after the library that now owns it (see

Kinsley, II: 5

The last lines of “Lament of Mary, Queen of

Scots,” from “Bixby B,” in Stevens (1908)

William K. Bixby’s manuscripts were

facsimiled to a much higher standard in Burns Club Facsimiles, edited by

Stevens (St Louis, 1908). Connecting “Mr Upcott,” Smith, Bixby, and the

Huntington pushes back the provenance of the Bixby/Huntington manuscript

a further seventy years, to 1840, long before the major period of Burns

forgeries, and it also provides useful confirmation that the earlier

facsimiles can provide accurate detailed textual information.

Some of the smaller-format guides giving short snippets of Burns’s

handwriting were probably less scrupulous. The issues involved in

assessing less pretentious guides are illustrated by the Burns excerpt

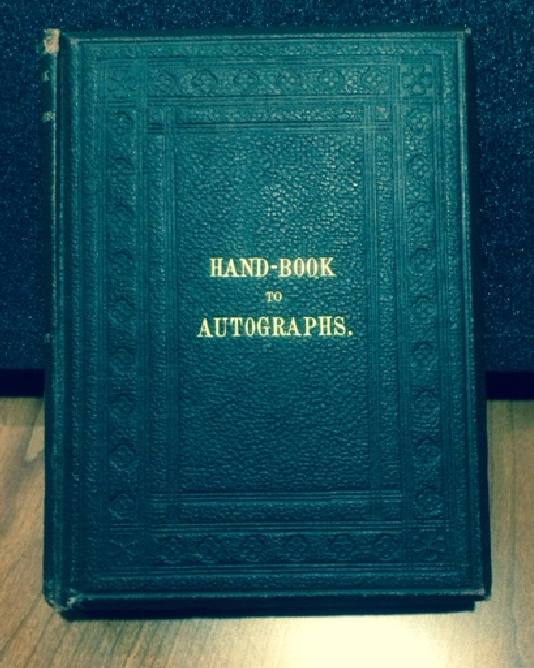

in Frederick Netherclift’s Handbook of Autographs (1862). Netherclift’s

father Joseph had published two large-format folio volumes of

autographs, in 1835 and 1849, and Frederick had published another folio

collection in 1855. His Handbook of Autographs was a much smaller book,

designed to help “the amateur collector of original writings” and the

“frequenter of old book-stalls” guard against fraud (p. 2). Nothing on

the title-page, or in library catalogues, would alert you that the book

has anything to do with Burns:

Frederick Netherclift, Handbook of

Autographs (1862)

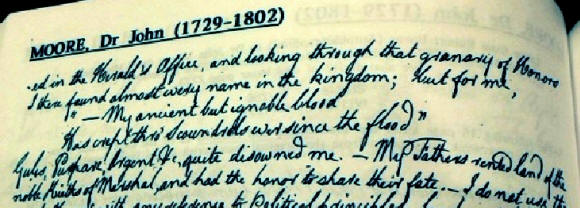

The book is arranged more or less

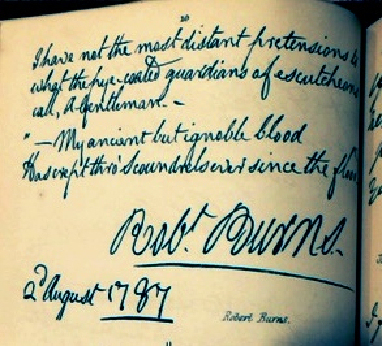

chronologically, with several examples to a page, and Burns is

represented by a passage from his famous letter to Dr. John Moore,

followed by a signature:

Burns, from letter to Dr. John Moore August

1787, in Netherclift, Handbook of Autographs (1862)

There is only one known manuscript of the

letter to Moore, in the British (Museum) Library, though there is also a

transcript in another hand, corrected by Burns, in the Glenriddell

Manuscript. Currie had apparently used a third source, Burns’s own

draft, rather than the letter itself, but the draft he used now survives

only in fragments, in the National Library of Scotland (cf. Westwood,

III, pt 2, 2273-2280). As the preface to Netherclift’s Handbook, by

Richard Sims of the British Museum, makes clear, nearly all the

facsimiles are taken from collections there. Fortunately, the Roy

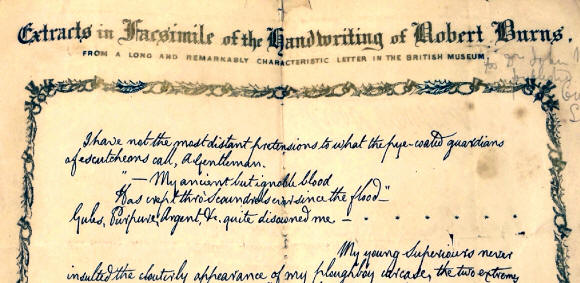

Collection has another of Netherclift’s productions, the single-page

Extracts in Facsimile of the Handwriting of Robert Burns (undated but

probably before 1860), which has the same excerpt, there clearly

labelled as from the British Museum, Unfortunately, the Extracts also

make clear that Netherclift felt free to rearrange Burns writing so that

the excerpt would fit on the page:

Burns, from letter to Dr. John Moore August

1787, from Netherclift, Extracts [1860?]

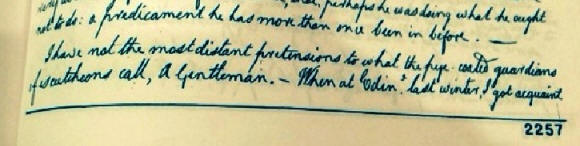

In fact, Netherclift has not only re-arranged, but

significantly shortened, the extract—it becomes an extract of an

extract. Peter Westwood provides a fuller version of the British

Library manuscript, though not quite a facsimile. Because his original

copy was too weak to reproduce and didn’t fit his page-size, Mr Westwood

traced it and also reformatted it to fit his pages, though much more

accurately than his Victorian precursor (Westwood, III, pt. 2, pp.

2257-2272; extract on pp. 2257-2258):

Burns, from Letter to John Moore, British

Library MS, from Westwood

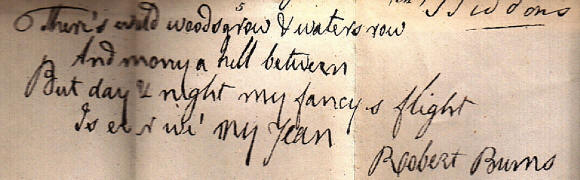

With this cautionary tale in mind, we can turn to

some older autograph guides that seem to preserve manuscripts that are now

missing. Typical is the Burns item illustrated in Edward Lumley’s little book,

The Art of Judging the Character of Individuals from their Handwriting and Style

(1875). This is a compilation of essays from different sources, with foldout

illustrations each carrying five or six different handwriting samples. The Burns

example is four lines from the song “Of a’ the airts,” accompanied by a sample

signature from some other source:

Burns, “Of a’ the airts,” lines 5-8, from Lumley,

Art of Judging (1875), plate 23.

The

song was first published in the Scots Musical Museum in 1790 (SMM III, song

235), and Kinsley supplies variants from the Hastie MS in the British Library,

the first publication, and several posthumous appearances (Kinsley I: 421-422,

titled “I love my Jean”). Kinsley does not, however, record a striking variant

in line 5, where this facsimile reads “waters row,” and all other sources have

“rivers row.” The Hastie MS is the only one on record, and the Index to English

Literary Manuscripts notes that it has been crossed through or cancelled, while

Lumley’s facsimile shows no cancellation (Smith and Boumehla, p. 131). Is

Lumley’s Burns sample a complete fabrication, which seems unlikely, or a

careless tracing from the Hastie MS, in preparation for using lithography,

omitting the crossing-out and miswriting the variant words, or is Lumley’s

extract and its variant the only extant portion of a lost Burns manuscript?

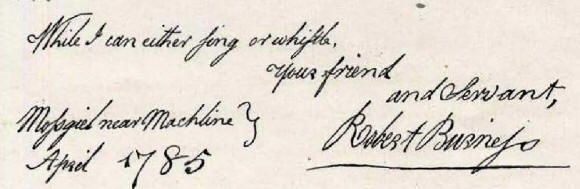

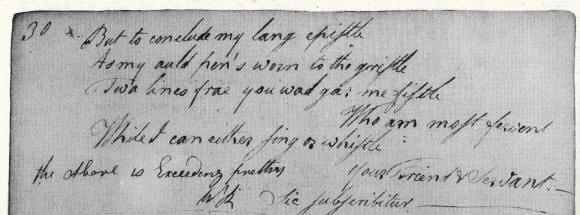

In 1894, the Burns collector William Craibe Angus contribute a short section

specifically on Burns to T.J. Wise’s Reference Catalogue of British and Foreign

Autographs and Manuscripts. After the first number, Wise’s catalogue was limited

to 100 copies, and Craibe Angus’s section is now quite rare. Craibe Angus first

discusses the changes in Burns’s handwriting during his early career, and

illustrates Burns’s early hand by the conclusion to his epistle to John Lapraik,

in April 1785 (Kinsley, I: 89);

Burns, “Epistle to J. L*****k, An Old Scotch Bard,”

ll. 131-132, from Craibe Angus (1894), p. 4

No

separate manuscript is known of this poem, so the only known autograph

manuscript is the version that Burns copied into his First Commonplace Book

(Ewing and Cook, p. 30; cf. Leask, OERB, I: 60). Angus’s facsimile differs from

the Commonplace Book in the arrangement of the last line, in punctuation, and in

adding the place and date at bottom left:

Burns, “Epistle to J. L*****k, An Old Scotch Bard,”

ll. 131-132, from Ewing & Cook, p. 30.

More important, and much more substantial, is the second facsimile Craibe Angus

gives, to illustrate Burns’s later handwriting. This is a full four-page

facsimile of Burns’s important letter to the younger Patrick Millar [Peter

Millar], in March 1794 (Roy, II: 288-289). In the letter, Burns discusses his

difficult political position as a government employee, rejects the offer of a

regular stipend from a London newspaper, the Morning Chronicle, but says that he

still hoped to send the newspaper occasional items, indirectly and

pseudonymously. The letter had been partially published by Cromek in 1808, but

the first edition to print it at full length was Chambers-Wallace in 1896, so

Craibe Angus’s pamphlet may well be its first publication (Cromek, pp. 161-162;

Chambers-Wallace, IV: 116-117). The pamphlet doesn’t say who owned the MS. in

1894, but it had been sold at auction in the Pickering Sale at Sotheby’s in

1854, and in 1896, it was loaned for the great Glasgow exhibition by Thomas J.

Wise (Memorial Catalogue, part 1, p. 180, item 1243; cf. IELM, p. 180, BuR

1223). When Ferguson started work in the 1920s, the letter was owned by a Dr Hew

Morrison, and it was again sold at Sotheby’s in 1928. Neither Ferguson nor Roy

was able to use the original manuscript, and both relied instead on Craibe

Angus’s facsimile.

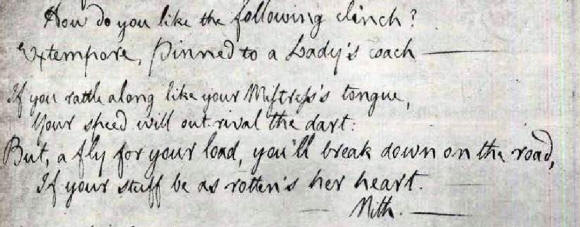

As well as being of significance for Burns’s political views, the letter is

important as including texts of three of Burns’s poems for the Morning

Chronicle. Among these is his scornful verse about Maria Riddell:

Burns, “Extempore, Pinned to a Lady’s Coach,” from

Craibe Angus (1894), pp. 5-8.

Neither Currie nor Cromek had printed this squib, and Chambers in 1852 had

declined to print it, as “totally indefensible” (Chambers, IV: 85). Burns made

at least four copies, but this manuscript hasn’t been seen since the 1920s, so

the Craibe Angus facsimile remains the sole source for the version Burns sent to

Millar.

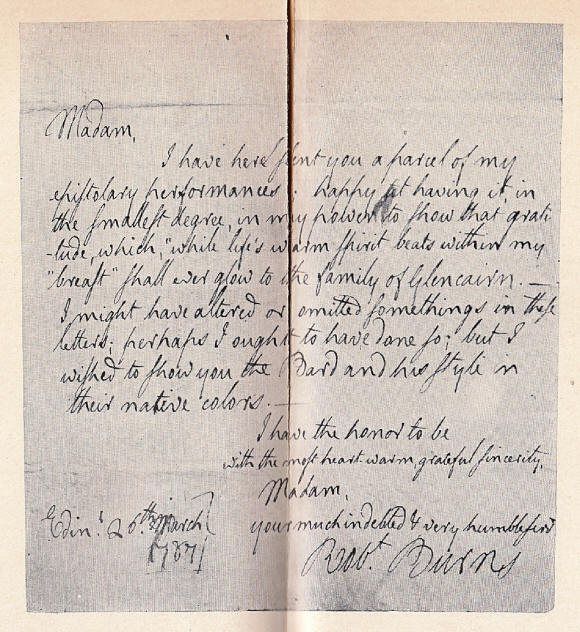

Here’s a final example of why these facsimiles matter. In March 1787, Burns

wrote to Lady Harriet Don, enclosing a group of manuscript poems (Roy I:

103-104). The letter is usually thought to have first been published by Ferguson

in 1931, based on a manuscript which was then in private hands (Ferguson I: 83).

By the time Ross Roy was working, the manuscript had vanished, and he had to

rely on Ferguson’s transcription. But the letter had earlier been reproduced in

facsimile, in 1902, with a full transcription, in A.H. Joline’s Meditations of

an Autograph Collector..

Burns, letter to Lady Harriet Don, March 1787, from

A. H. Joline (1902), after p. 78

Until the

manuscript turns up, Joline’s facsimile is not only the first publication of

this letter, but also the most authoritative source.

There must

be more such examples out there to be discovered. Over the years, some of the

facsimiles will have been noted here and there in the Burns editions or other

sources, but there seems to be no guide or list of this kind of Burns material,

especially when it is hidden away in books that cover many authors. Facsimiles

make an attractive and affordable kind of collecting for Burns enthusiasts who,

like me, will never own an original manuscript. The instances noted here surely

underline the ongoing need for Burns collectors and Burns researchers to have

much better bibliographical coverage of such material.

References

Angus, W. Craibe, and H.D.

Colvill-Scott, “The Autograph of Robert Burns,” Part II, in Thomas J. Wise, ed.,

A Reference Catalogue of British and Foreign Autographs and Manuscripts

(London: for Members of the Society of Archivists, 1894).

Croft, P.J., comp.,

Autograph Poetry in the English Language: Facsimiles of Original Manuscripts

from the Fourteenth to the Twentieth Centuries, 2 vols. (London: Cassell,

1973).

Eaton, Seymour, ed., Robert

Burns: Rare Print Collection (Philadelphis: R.G. Kennedy, “for private

circulation,” [1900]).

Ewing, J. C., and Davidson

Cook, eds,, Robert Burns’s Commonplace Book 1783-1785 (Glasgow: Gowans

and Gray, 1938; repr. London: Centaur Press; Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois

University Press, 1965).

Ferguson, J. De Lancey, ed.,

The Letters of Robert Burns, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931).

[Gribbel, John], The

Glenriddell Manuscripts of Robert Burns, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: John

Gribbel, 1914); reprinted with intro by Desmond Donaldson in one vol.

(Wakefield: E.P. Publishing; Hamden, CT: Archon, 1973).

Jolene, Adrian Hoffman,

Meditations of an Autograph Collector (New York: Harper Brothers, 1902).

Kinsley, James., ed., Poems

and Songs of Robert Burns, 3 vols., (Clarendon Press, 1968).

Leask, Nigel, ed.,

Commonplace Books, Tour Journals, and Miscellaneous Prose [The Oxford

Edition of the Works of Robert Burns, vol. I] (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2014).

Lumley, Edward, The Art of

Judging the Character of Individuals from their Handwriting and Style

(London: John Russel Smith, 1875).

Mole, Tom, What the

Victorians Made of Romanticism: Material Artifacts, Cultural Practices, and

Reception History (Princeton UP, 2017).

Netherclift, Frederick G.,

Extracts in Facsimile of the Handwriting of Robert Burns From a Long and

Remarkable Characteristic Letter in the British Library (London: F. G.

Netherclift, lithographer, n.d. [1860]).

___________________, The

hand-book to autographs: being a ready guide to the handwriting of distinguished

men and women of every nation, designed for the use of literary men, autograph

collectors and others (London: John Russell Smith, 1862).

Roy, G. Ross, ed., The

Letters of Robert Burns, revd ed., 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985).

Scott,

Henry T., M.D., and Samuel Davey, F.R.S.L., A guide to the collector of

historical documents, literary manuscripts, and autograph letters, etc. With an

index of valuable books of reference, where several thousand facsimiles of

handwriting may be found for the verification of mss. and autograph letters;

also a new edition of Wright's Court-hand restored; with an introductory chapter

for the use of students and facsimiles of watermarks (London: S.J. Davey, 1891).

_____________, Autograph

collecting: a practical manual for amateurs and historical students: Containing

ample information on the selection and arrangement of autographs, the detection

of forged specimens, &c., &c : To which are added numerous facsimiles for study

and reference, and an extensive valuation table (London: L. Upcott Gill,

1894).

Smith, Charles John,

Historical and Literary Curiosities: Consisting of Fac-similes of Original

Documents (issued in 8 parts, 1835-1840; completed by H. G. Bohn; London: H.

G. Bohn, 1847; London: H.G. Bohn, 1852; London: Chatto and Windus, 1875).

Smith, Margaret M., and Penny

Boumelha, comps., “Robert Burns,” in Index of English Literary Manuscripts,

vol. III, Part I (London and New York: Mansell, 1986), 93-193.

Walter B. Stevens, ed.,

Poems and Letters in the Handwriting of Robert Burns reproduced in facsimile

through the courtesy of William K. Bixby and Frederick W. Lehmann (St.

Louis, MO: Printed for the Burns Club, 1908).

Warner,

George F., ed., Universal Classic Manuscripts, fac-similes from originals in

the Department of Manuscripts, British Museum, of royal, historic and diplomatic

documents, letters, and autographs of kings, queens, princes, statesmen,

generals, authors, etc. With descriptions, editorial notes, references and

translations, 2 vols. (Washington: M.W. Dunne, [1901]).

Westwood, Peter, ed., The

Definitive Illustration Companion to Robert Burns, 8 vols [15 parts]

([Irvine]: privately published in conjunction with the Distributed National

Burns Collections Project, 2004) |