|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

Once again Professor Patrick Scott has

stepped to the forefront of our contributors to offer an unusual article

on a Burns Broadside at auction in Macon, Georgia, an unusual place to

find an original piece of the Bard’s works for sale. It is with deep

gratitude that I thank Dr. Scott for his many articles to Robert Burns

Lives! and once again salute his scholarship. Over many years he has

been of enormous help to this website and to me personally. With his

being a member of the top echelon of Burns scholars, our readers have

benefited greatly from Patrick’s contributions. It is always a joy to

have him share another of his articles. Yes, as the old western saying

goes, “He will do to ride the river with.” (FRS: 11.17.16)

Burns and Broadside Publication "The Chevalier's

Lament" at Auction in Macon, Georgia

By Patrick Scott

A couple of weeks ago, I got

emails from two different contacts about an early and possibly unique Burns item

that was coming up for auction in Macon, Georgia. It was a broadside, or single

sheet, printed on one side with two songs, and one was the short Burns song that

begins “The small birds rejoice in the green leaves returning” (Kinsley I: 412;

K 220), here titled, as in James Currie’s edition, “The Chevalier’s Lament.” It

was undated, but the auction house, Addison & Sarova, had a detailed description

on their web-site, and made a cautious estimate that it was printed in or about

1799:

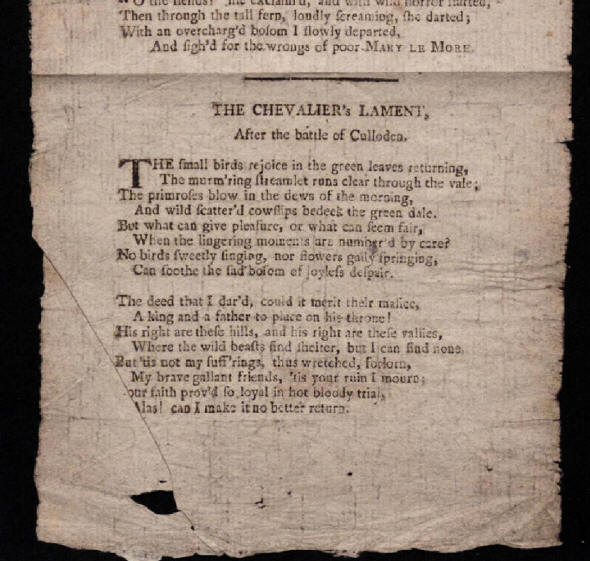

Lot 226: [Burns, Robert.]

THE CHEVALIER'S LAMENT. N.d, n.p, circa 1799. Broadside, also featuring a poem

entitled "The Maniac" by another author. 13.5" x 5". Laid paper. Toned, several

creases small hole to lower blank margin, rather worn with some fraying to

edges. A very scarce broadside for which we find no record. The type of paper

and use of the long "s" in the text certainly suggest a date of 1800 or earlier.

At the very least, it would seem that this would be the first publication of

this work in broadside form.

The site also provided

several images of the item, which are used here with their permission. The first

image gave a close-up of the Burns song, which comes at the foot of the

broadside page:

Fig. 1: “The Chevalier’s

Lament,” from an undated broadside

Image courtesy of Addison & Sarova, Macon, GA.

Of the early formats in

which Burns’s poetry was printed, broadsides are among the most intriguing but

least understood. They were the simplest but also the most ephemeral kind of

printed poetry, hawked by itinerant vendors who commonly sang the songs from the

broadsheets as a way of advertising what was for sale. They were difficult to

keep clean or store safely, so the survival rate is low. But because they were

cheap and quick to produce, broadsides were often used in the Burns period and

the early 19th century for improvised ballads commenting on

contemporary events. The best-known Burns broadsides are of this kind. In 1789,

Burns had his satire on the Auld Licht ultra-orthodox ministers, The Ayrshire

Garland, printed in Dumfries in broadside format (Egerer 15, better known as

“The Kirk’s Alarm”). In the mid-1790s, when he wrote several songs as election

propaganda, they also were first published in broadside format (Egerer 31 a, b,

c,). There are fold-out facsimiles of these items in J. C. Ewing’s Burns

bibliography (1909), and several have been digitized by the Robert Burns

Birthplace Museum and BurnsScotland.

But both in Burns’s lifetime

and after, there were other broadsides printed independently of Burns himself,

that had simply reprinted Burns poems and songs because they were popular and

likely to sell. This is largely uncharted territory. Over the years, there has

been recurrent interest in broadsides, as there has been in chapbooks, because

they show popular interests and taste—in Ted Cowan’s phrase, they preserve “The

People’s Past.” Many years ago, I did an index to one of the major Victorian

broadside collections, and began to realize just how much material was out there

and how many scholars have written about the broadside phenomenon (see e.g. in

the reference list under Welsh and Tillinghast, Shepard, Neuberg, Roy, McNaugtan,

Cowan and Paterson, Connell and Leask, Fox, Atkinson and Roud), yet there is

still little directly on Burns and broadsides. There are lots of them. A major

web-site, Bodleian Ballads Online, gives 196 hits just for broadsides that

contain poems and songs by Burns, with an excellent indexing system for

searching ballads, publishers, and even illustrations (http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/).

The Roy Collection has a handful of Burns broadsides, but none earlier than

1810. There is no comprehensive list or database of Burns broadsides, and only

the very few broadsides believed to be the first publication of the Burns poem

concerned were included in Egerer’s Burns bibliography.

Dating a broadside like the

one in the Macon auction, which carries no place, printer’s name or date, means

combining research with educated guesswork about what needs researching.

Sometimes a printer can be identified when the broadside has a woodblock

illustration which can be traced in other publications from the same shop (the

Bodleian site has a special ImageMatch program to help with this), but the Macon

broadside has no illustration. Typography is often a clue, here suggesting an

early date, but it is not an exact clue. The sort of jobbing printer who printed

broadsides wasn’t necessarily up-to-date and so may not have dropped the

long-form “s” as promptly as his more ambitious competitors.

One starting point is the

Burns song itself, which, with just two stanzas, is the second and shorter of

the two songs on the new broadside. It is written in the voice of Prince

Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) after the Jacobite defeat at

Culloden in April 1746, contrasting the coming of spring (“The small birds

rejoice in the green leaves returning”) with the ruin that defeat brought to the

Prince’s “brave, gallant friends” (Kinsley I: 411-412). Burns wrote the opening

stanza in 1788. As he wrote to his friend Robert Cleghorn on March 3st:

Yesterday, my dear Sir, as I

was riding thro’ a parcel of damned melancholy, joyless muirs, between Galloway

and Ayrshire; it being Sunday, I turned my thoughts to “Psalms and hymns and

spiritual songs;” and your favourite air, Captn Okean, coming in my head, I

tried these words to it—You will see that the first part of the tune must be

repeated.… I am tolerably pleased with these verses, but as I have only a sketch

of the tune, I leave it with you to try if they suit the measure of the music

(Roy, Letters, I: 269-270).

At this point Burns had only

written the first eight lines. “Song.” In his reply, Cleghorn suggested slightly

mischievously that the song could be performed in the voice of the Jacobite

Prince: “Suppose it should be sung after the fatal field of Culloden by the

unfortunate Charles” (Currie, II: 130-131). After all, Burns himself had

Jacobite forebears, and in 1788 the song would have seemed a romantic

counterpoint to the smug centenary celebrations then in progress for the

Glorious Revolution of 1688 that had sent Charles’s grandfather into exile. It

isn’t clear when Burns added the second stanza, which makes the song explicitly

Jacobite, as the voice of Charles leaving Scotland in defeat. In April 1703, he

commented to George Thomson that his song “Banks of Dee,” which Thomson wanted

for his Selection Collection, had “false imagery,” and that “If I could hit on

another Stanza, equal to, “The small birds rejoice &c., I do myself honestly

avow that I think it a superiour song” (Letters, II: 206). It seems

improbable, however, that if five years had passed Burns would add a stanza so

closely on the lines Cleghorn had suggested in 1788, and there is a full

version, with both stanzas apparently written out at the same time, in the

manuscript notebook known as the Second Commonplace Book, purchased in April

1787, but used intensively from June 1788 onwards (Leask, 98-99). Many of the

poems Burns copied into the notebook, such as “Written in Friar’s Carse

Hermitage,” were written at Ellisland in 1788, and there seems little reason to

doubt that this song was completed the same year. The 1793 letter expresses his

relative dissatisfaction with the second stanza, rather than documenting its

non-completion.

But Burns himself never

published it. The first publication is usually given as 1799, in George

Thomson’s Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs, part 4, song 97 (Egerer

item 28d, p. 47). It was also issued that same year much less expensively in

two small chapbooks or pamphlets, one published in Glasgow by Stewart and Meikle

as the eighth of their Burns chapbooks (probably printed in the first week of

September 1799: Egerer item 45, p. 64), and the other in Edinburgh as the second

of the Gray Tracts, Sonnets from the Robbers, by Alex. Thomson, Esq. …

(Edinburgh: George Gray, 1799), pp. 14-15 (not seen by Egerer but see his

footnote 7, p. 59). The following year, the song was also included in Dr. James

Currie’s edition of Burns’s Works, volume II, and the Stewart and Meikle

chapbook was included in the Poetical Miscellany (Glasgow: Chapman and

Lang for Stewart and Meikle, 1800). Later, despite its recent composition, it

would also be included, with attribution to Burns, in James Hogg’s Jacobite

Relics of Scotland, Second Series (1821: Pittock, pp. 419-20, 434, 527).

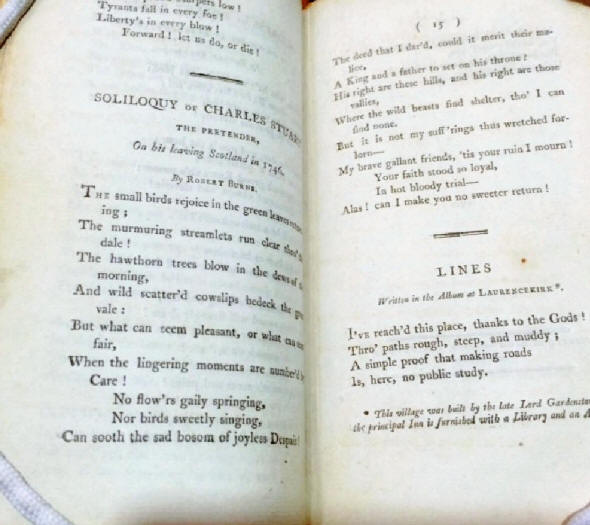

Fig. 2, “The Soliloquy

of Charles Stuart the Pretender,” from Sonnets from the Robbers

(Edinburgh: George Gray, 1799).

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection, University of South Carolina

Libraries.

Each of these publications

differs in one way or another from the others in title or textual details, and

these differences can be a clue to where the broadside printer got his text.

Thomson can be ruled out as source, because he heads the song with its first

line, “The small birds rejoice, &c. From a MS.,” and has small variants also in

lines 1 and 12. (Carol McGuirk has recently argued that Thomson’s

“noncommittal” heading for the poem, like Burns’s simple heading “Song” in the

Commonplace Book, is more effective than the title that displaced them, because

an explicit title gives away the speaker’s identity too early: McGuirk, p. 123.)

The Gray chapbook can similarly be ruled out, because of its cover-title “The

Pretender’s Soliloquy,” and its internal title “Soliloquy of Charles Stuart the

Pretender, on his leaving Scotland in 1746” (and small textual variants in lines

3, 4, 4, 10, and 16). In using the title “The Chevalier’s Lament,” and in most

(but not quite all) textual variants, the broadside lines up with the Stewart

and Meikle chapbook, and the Currie edition, in 1800. One crucial textual

variant, however, in line 3, where the broadside has the usual reading “the

primroses blow,” shows it did not get its text directly from the Currie edition,

because that has “the hawthorntrees blow” (a reading shared otherwise only by

the Gray chapbook); there are minor variants between the broadside and Currie

also in lines 6, 15, and 16. The Currie text stays in the same in later editions

of the Works, through at least 1820. The text in Hogg’s Jacobite

Relics picks up minor variants from each of these sources.

The only remaining early

printed version close to the broadside is therefore the Stewart and Meikle

chapbook. The two agree not only in title, but in every textual variant. Either

one depends on the other, or they both depend on a common manuscript or

newspaper source. Aside from the Commonplace Book, neither of the other

recorded full-length manuscripts of “The Chevalier’s Lament” was known to or

collated by Kinsley, and neither is currently accessible: of the two, one was

last seen on exhibition in 1896, and the other at auction in 1930 (cf. Smith and

Boumelha, pp. 167-168). No early newspaper appearance has yet been recorded.

Where Stewart got his previously-unpublished Burns material has always been

murky, but once he had published the song, his text was also that used in

various unauthorized editions of Burns in the succeeding years, not only in the

Poetical Miscellany (1800), but also Stewart’s Edition (Glasgow,

1802). It is clear from all this that the Burns broadside is early, and did not

get its text from either of the two main published editions, Thomson in 1799 and

Currie in 1800, but it isn’t clear how early, or whether it had an independent

manuscript source.

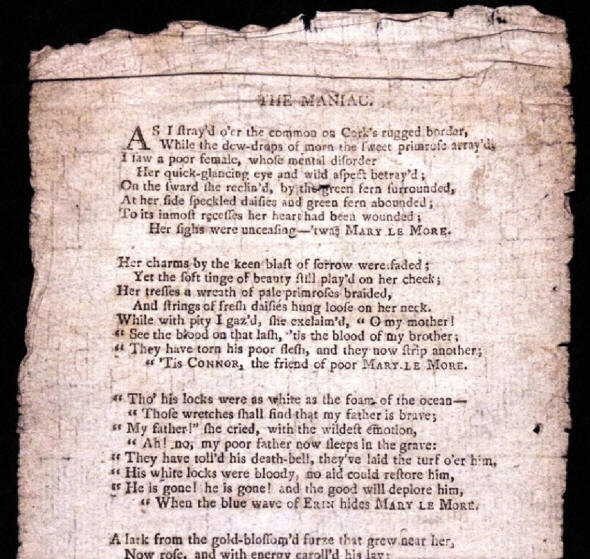

Fig. 3: Edward Rushton,

“The Maniac,” from an undated broadside

Image courtesy of Addison & Sarova, Macon, GA.

More clues can be picked up,

however, from the other item on the broadside which is printed first, ahead of

“The Chevalier’s Lament.” This is a six-stanza song titled “The Maniac,” which

is not by Burns, is not Scottish, and is not described or identified by the

auction house, but is still of great interest. The first line, “As I strayed

o’er the common on Cork’s rugged border,” and the refrain “Mary Le More,”

identify its setting as Irish, though in fact it was written by an Englishman.

It is second of three “Mary Le More” poems written by the radical Liverpool poet

Edward Rushton (1756-1814), describing the brutal reprisals after the United

Irishmen’s unsuccessful rising in 1798. Burnsians may remember that Rushton

also wrote a commemorative poem about Burns included in the Currie Works

(cf. Andrews, pp. 200-201).

The Rushton-Burns broadside

just auctioned cannot date earlier than the composition of the Rushton poem. The

first recorded publication of “The Maniac” was in the Monthly Magazine

for January 1800, under the heading “Original Poetry,” and Rushton’s three Mary

Le More poems were later included as a series in Rushton’s Poems

(Liverpool, 1806); the 1806 collection was printed by John M’Creery, who had

moved to London after he printed Currie’s edition of Burns. A recent book about

Rushton, by Franca Dellarosa reproduces an early broadside version of the first

Mary Le More poem, printed by W. Armstrong, Banastre Street, Liverpool, which

she dates [?1799], also noting that “The Maniac” was anthologized soon after

its magazine appearance by an Irish song book, Paddy’s Resource (1803) (Dellarosa,

pp. 85, 89); the Armstrong broadside is almost certainly much later, because

Armstrong is only recorded as in business in Liverpool from 1815-1824, and only

on Banastre Street in the years 1820-1823 (Perkin, 1987, fiche 1, p. 4; not

listed in Perkin, 1981). In addition the Amstrong broadside of the first poem

(now in the New York Public Library) has been typeset with the regular “s,”

which would fit better with a later date. In her commentary on the poem itself,

rather than the particular broadside, Dellarosa suggests an even earlier date

thn 1799, quoting a near-contemporary history of the 1798 rising, published in

1799, that describes the United Irishmen as they went into the attack on Vinegar

Hill on June 21, 1798, “singing the pathetic ballad of Ellen O Moor,” which is

then footnoted as matching exactly the opening stanzas of the Rushton poem (p.

84). Frankly, it seems improbable that even the first of Rushton’s three poems

would predate the 1798 rising, and “The Maniac” describes the violent government

reprisals after the rising, rather than the fighting itself. However, Dellarosa

also cites a letter in the Home Office files dated January 1, 1799, from a

government informer in Nottingham, reporting, and apparently enclosing, a

broadside of “Mary le More” that had been circulating in that town (Emsley, pp.

541 and n. 4; Dellarosa, pp. 84-85). At least some portion of the poem had been

written, and reached Nottingham, far across England from Rushton’s home city,

before the end of 1798.

I had high hopes that

Bodleian Ballads Online would cast more light on all this. The Bodleian website

has 249 entries for Armstrong (172 from Banastre Street), but of these 246 are

dated, or have estimated dates, after 1800; none of the 249 include “The Maniac”

or “Mary le More.” (For comparison, the Welsh-Tillinghast bibliography of

broadsides and chapbooks at Harvard includes only one broadside printed in

Liverpool, and only one item, a chapbook, printed by Armstrong). Ten of

Armstrong’s broadsides on the Bodleian site have poems by Burns, and for those

the Bodleian project uniformly estimates the dates as between 1820 and 1824;

this dating fits the dates already cited for Armstrong’s printing business from

Liverpool trade directories (Perkin, 1987, fiche 1, p. 4). None of the Armstrong

Burns broadsides in the Bodleian database use the long “s.” The Bodleian

project also lists one broadside printed in London by J. M’Creery, formerly of

Liverpool; this broadside was a song from 1819 about the radical politician John

Cam Hobhouse. M’Creery was in business in Liverpool across the relevant years,

appearing in directories from 1792-1805, when he moved to London (Perkin, 1981,

p. 18; Perkin, 1987, fiche 3, p. 140; and cf. Barker and Isaac). As one might

expect, M’Creery’s standard of printing in the 1819 broadside is much higher

than that seen in the broadside that was auctioned, and he used the short “s” as

early as 1795, in printing William Roscoe’s Life of Lorenzo De’ Medici,

as also in the Currie Works (1800), but that perhaps would not preclude

him or one of his journeymen having printed a broadside for the popular market

in the common style. Giles Bergel suggested to me in an email the possibility,

also, that for a printer like M’Creery, using the long “s” might be a way of

making the broadside look older or more downmarket in provenance, and so

deflecting or diminishing the risk of identification and legal responsibility.

Aside from that possibility, the Rushton-Burns broadside must be dated

significantly earlier than the Bodleian Armstrong or M’Creery broadsides,

because of its rough-edged laid paper and its typography; Given the huge amount

of data on the Bodleian site, the non-appearance of this example is dispiriting

evidence of just how many broadsides must have been lost, and (less

dispiritingly) how rare many of those that survive must be.

If one can persuade oneself

that Rushton wrote all three parts of his sequence, including the second part,

in 1798 or early in 1799, and that the broadside was printed immediately, this

would make the Macon broadside the very first appearance in print of Burns’s

song “The Chevalier’s Lament.” Perhaps it was another copy of this very

broadside that the government informer in Nottingham picked up and mailed in to

the Home Office in January 1799 as evidence of sedition. His primary government

handler was not impressed, docketing the letter “I don’t think this song will do

much harm,” but the correspondence is still in the files (Public Record Office:

Home Office papers, 42.46.1, January 1 1799), so maybe some future Burns

researcher will be able to find out which “Mary le More” poem was already in

print by that date.

The real difficulty to a

very early date for the Rushton-Burns broadside comes from the Burns side, not

the Rushton. The Liverpool connection makes it just possible that Rushton

himself, or whoever was printing the broadside, was also friendly or in contact

with James Currie or his friend William Roscoe, and got hold of the Burns song

directly in manuscript, before it was published in the chapbooks or in Thomson’s

Select Collection. M’Creery also provides a possible source for the Burns

song. M’Creery, born and brought up in Strathbane, County Tyrone, had been

apprenticed to his father there and then tone of the leading Liverpool printers.

In 1792, with Roscoe’s encouragement, he had set up his own printing-shop,

working on books both for Roscoe and Currie (Barker, pp. 82-83). Like Rushton,

he was known to be liberal in politics. In his own beautifully-printed poem

The Press (1803: pp. 27-28), M’Creery includes Rushton among the authors for

whom he had done printing work, and in his later continuation he commemorates

Rushton as “a true friend to liberty” (1820, p. 75). It is not, of course,

necessary to argue that M’Creery printed the broadside, or that Rushton was

directly involved in arranging the printing, or even that it was printed in

Liverpool, for one or both of them to have been the channel through which the

Burns poem reached the broadside printer. Whatever the channel or connection

through which Rushton or M’Creery or another printer got hold of Burns’s

unpublished poem for using in the broadside, the manuscript he got hold of could

not be the one Currie used for the Works: it had to be exactly the same

in all textual details to the text Stewart would use for his Glasgow chapbook in

September 1797. Making the broadside earlier than the chapbook would probably

mean that Stewart got his text from the broadside, because no two printers are

likely to set even the same manuscript copy with absolutely no small

differences.

That scenario, where the

broadside was the first published appearance of Burns’s poem, remains a

possibility, but it still seems more likely that when Rushton’s poem was printed

as a broadside, Burns’s song had already appeared in print. If so, the

broadside printer was working from the Stewart & Meikle chapbook or one of its

derivatives. Not only its brevity and Burns’s selling-power but the similarity

of theme would have made “The Chevalier’s Lament” an appropriate selection to

fill up the page below Rushton’s longer and more topical poem. As the

Victorian Irish historian of 1798 pointed out, the Jacobite songs provided an

important precedent for collecting the songs of the United Irishmen: “The very

fact of failure … gives an adventitious interest to all that concerns the actors

in a struggle, against whom great power or great oppression has prevailed”

(Madden, p. x, quoted in Dellarosa, p. 80).

Working on this research

while waiting for the auction, I came to appreciate and respect the auction

house description, which is quite properly cautious in estimating the

broadside’s date. It hits about the right balance between enthusiasm for it as

the first recorded broadside appearance of Burns’s song (which it certainly is)

and restraint over claiming it to be the first published appearance in any

format (which is certainly possible). The newly-discovered broadside is an

intriguing and visually attractive and highly collectible item. It highlights

some significant issues for future Burns editors about the relationship among

the various early printed versions of Burns’s song. The long rows of old

printed auction catalogues, like old dealer catalogues, are often a major

resource for research on Burns manuscripts, or the rarest printed items, as they

emerge briefly into the light of day for a sale, and then disappear again into

the safety of private ownership. The same is now increasingly true of online

descriptions, but there is less certainty that they will be available to

researchers fifty or a hundred years from now. I hope they will be. .

I wish I could end by

reporting that the library’s auction bid had been successful. Three bidders had

registered bids in the days before the auction went live, and the library had

placed a bid we hoped would be competitive. But now even auction houses in

relatively small cities, well away from the major houses in New York or San

Francisco, can use live on-line bidding to attract national, and even

international, participation. In the event, the broadside got away. Someone

else wanted it more, estimated collector interest more accurately, and outbid

us. I doubt we’ll see this same broadside for sale again anytime soon, or indeed

ever, but one mustn’t have too many regrets. Its recent appearance at the

auction in Macon, Georgia, not only brought to light something important that

was not previously recorded in the standard Burns reference sources: it also

draws attention to a kind of early printed Burnsiana that is still virtually

uncharted and that often gets overlooked.

References

I wish to thank Mr. Michael

Addison of Addison and Sarova, Macon, Georgia, for permission to use images from

the auction catalogue. I should like to thank also Giles Bergel, Craig Lamont,

and Murray Pittock for reading this article in draft, though none of them is

responsible for my conclusions.

Addison and Sarova, Sale

1014: Rare and Fine Books (Macon, Georgia, November 5, 2016), lot 226:

http://addisonsauction.hibid.com/lot/27819221/robert-burns---chevaliers-lament--broadside-/?cpage=5&ref=catalog

Andrews, Corey E., The

Genius of Scotland: the Cultural Production of Robert Burns, 1785-1834

[SCROLL vol. 24] (Leiden: Brill Rodopi, 2015).

Atkinson, David, and Steven

Roud, eds., Street Ballads in Nineteenth-Century Britain, Ireland and North

America (London: Routledge, 2014).

Barker, J.R., “John McCreery:

a radical printer, 1768-1832),” The Library, 5th ser., 16

(1961): 81-103.

Bodleian Ballads Online

(Bodleian Library, Oxford):

http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/

or for the Burns broadsides:only:

http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/search/?query=Robert%20burns&page=2

Connell, Philip, and Nigel

Leask, eds,, Romanticism and Popular Culture in Britain and Ireland

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Cowan, Edward J., ed.,

The People’s Past (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1993).

_______________, “Chapman

Billies and their Books,” Studies in Scottish Literature, 35-36 (2007):

6-25.

http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/3/

Currie, James, ed., Works

of Robert Burns, 4 vols. (Liverpool: M’Creery; London: Cadell and Davies,

1800).

Dellarosa, Franca,

Talking Revolution:

Edward Rushton’s Rebellious

Poetics, 1782-1814

(Liverpool: Liverpool

University Press, 2014).

Egerer, J.W., A

Bibliography of Robert Burns (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1964: Carbondale,

IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965).

Emsley, Clive, “The Home

Office and Its Sources of Information and Investigation, 1791-1801,” English

Historical Review, 94:3 [no. 372) (July 1979): 532-561.

Ewing, J. C.,

Bibliography of Robert Burns, 1759-1796 (Edinburgh: privately printed,

1909).

Fox, Adam, “The Emergence of

the Scottish Broadside Ballad in the Late 17th and Early 18th

Centuries,” Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 31:2 (October 2011):

169-194.

Isaac, Peter, “M’Creery,

John (1768-1832),” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004),

consulted online.

Kinsley, James, ed., The

Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968).

Madden, Richard Robert, ed., Literary Remains of the United Irishmen of 1798,

and Selections from other popular Lyrics of their Times, with an Essay on the

Authorship of ‘The Exile of Erin’ (Dublin: James Duffy and Sons, 1887)

M’Creery, John, The

Press, a Poem: published as a specimen of typography [part 1] (Liverpool:

M’Creery, 1803); part the second (London: Cadell and Davies, 1820).

McGuirk, Carol,

Reading Robert

Burns: Texts, Contexts, Transformations

[Poetry and Song in the Age of Revolution, no. 6] (London: Pickering & Chatto,

2014).

McNaughtan, Adam, "A Century

of Saltmarket Literature, 1790-1890," in Peter Isaac, ed. Six Centuries of

the Provincial Booktrade in Britain (Winchester: St. Paul's, 1990), 165-180.

Leask, Nigel, ed.,

Commonplace Books, Tour Journals, and Miscellaneous Prose [Oxford Edition of

Robert Burns, vol. I] (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 98-99

--for the relevant

manuiscript page, see also:

http://www.burnsmuseum.org.uk/collections/transcript/1154

Morris, John, "Scottish

Ballads and Chapbooks," in Peter Isaac and Barry McKay, eds. Images and

Texts: Their Production and Distribution in the 18th and 19th Centuries (New

Castle, DE: Oak Knoll, 1997), 89-111.

Neuburg, Victor E.,

Popular Literature: A History and Guide (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977).

Perkin, M.R., ed., The

Book Trade in Liverpool to 1805: A Directory [Book Trade in the North West

Project Occasional Publications, 1] (Liverpool: Liverpool Bibliographical

Society, 1981).

______________, The Book

Trade in Liverpool 1806-1850: A Directory [Book Trade in the North West

Project Occasional Publications, 2] (Liverpool: Liverpool Bibliographical

Society, 1987).

Pittock, Murray, ed., The

Jacobite Relics of Scotland, Second Series, Collected by James Hogg

[Stirling-South Carolina Edition of James Hogg, vol.12] (Edinburgh: Edinburgh

University Press, 2003).

Robert Burns Birthplace

Museum: digital images of election ballads, at e.g.:

http://www.burnsmuseum.org.uk/collections/object_detail/3.474

Roy, G. Ross, “Some Notes on

Scottish Chapbooks,” Scottish Literary Journal, 1:1 (1974): 50-60.

Rushton, Edward, Poems

(London: Printed for T. Ostell .. by J M’Creery, 1806).

Scott, Patrick, An Index

to Charles Hindley’s Curiosities of Street Literature (Leicester: Victorian

Studies Centre, 1969).

Shepard, Leslie, The

Broadside Ballad: A Study in Origins and Meaning (London: Herbert Jenkins,

1962).

_____________, John

Pitts: ballad printer of Seven Dials (London: Private Libraries Association,

1969).

_____________, The

History of Street Literature (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1973).

Smith, Margaret M., and Penny Boumelha, comps.,

“Robert Burns,” in Index of English Literary Manuscripts, vol. III, Part

I (London and New York: Mansell, 1986), 93-193.

Thomson, George, A Select

Collection of Original Scotish Airs, part 4 (London: Preston, 1799).

Welsh, Charles, & William H.

Tillinghast, Catalogue of English and American Chapbooks and Broadside

Ballads in Harvard College Library (Orig. Cambridge, MA, 1905; rep. with an

introduction by Leslie Shepard, Detroit: Singing Tree Press, 1968). |