|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

I have met

several men in my lifetime that I hold in deepest respect and,

ironically, many of them are in academic affairs and are much more than

gentlemanly scholars. Their work is not a burden to them or their

families, and it is a joy to be in their midst whether it be at club

meetings, conferences or social gatherings. One of those special persons

is Professor Patrick Scott who recently retired from the University of

South Carolina and who has written many articles for magazines, journals

and books throughout his career. Patrick may be retired but he is still

working, cranking out articles for various publications, books and

quarterly reviews. He has been a staunch supporter of the Robert Burns

Lives! website from inception many years ago. Again, it is an honor to

welcome Patrick to the pages of our humble site! (FRS: 8.17.16)

THE TWA BARDS:

ROBERT BURNS AND WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

By Patrick Scott

April 23, 2016, marked the four-hundredth anniversary of

the Other Bard, William Shakespeare. In the early and mid-19th

century, comparisons between Burns and Shakespeare were fairly common.

Both were authors with worldwide significance, both seemed to transcend

narrow particularities of time or ideology, and both produced many

memorable lines that have passed into common speech. As Walter Scott

once commented in his journal, “Long life to your fame and peace to your

soul, Robert Burns! When I want to express a sentiment which I feel

strongly, I find the phrase in Shakespeare—or thee” (Low, p. 260). This

year, at the Birthplace Museum, the annual January Burns conference

associated with Glasgow’s Centre for Robert Burns Studies marked the

Shakespeare anniversary by discussing the Two Bards, the first academic

conference ever to do so, and in April, when our library was mounting a

major Shakespeare exhibition, we therefore included a case on Burns

illustrating their literary relationship. The Shakespeare exhibition

included a borrowed copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio (under armed

guard); it is worth noting that the Burns Kilmarnock is three times

rarer than the Shakespeare folio.

The iconic status of Shakespeare and Burns as National Bards can be summed up by

their best-known portraits. Droeshout’s frontispiece portrait of Shakespeare, in

the first Folio, and the Nasmyth/Beugo frontispiece portrait of Burns, in the

Edinburgh edition, are both instantly recognizable in a way matched by the

portraits of no other British writer.

For both poets, also,

their reputation as national figures has been closely related to the parallel

development of the two birthplaces, Stratford-on-Avon and Alloway, as places of

literary pilgrimage, helped by the nineteenth-century spread of the railway

network.

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection,

University of South Carolina Libraries.

This development even

encouraged the production of similar souvenirs for the visitors, like the two

Mauchline Ware boxes shown above. Mauchline Ware souvenirs were first produced

in Mauchline, Ayrshire, for Burns, before diversifying to mementoes of many

other places, including Scott’s Abbotsford and Shakespeare’s Stratford

(Trachtenberg and Keith, pp. 26-31, 130-140: James Mackay, pp. 140-145; Pauline

Mackay). The Burns Mauchline Ware box on the left was a gift to the Roy

Collection by Thomas Keith, and an elderly neighbor gave me the Shakespeare box

on the rght in the early 1950s.

As Donald Low’s invaluable Critical Heritage volume shows, the comparison

between the two poets dates back to Burns’s first appearance in “guid black

prent.” Reviewing the Kilmarnock edition in 1786, Henry Mackenzie saw in Burns

“that intuitive glance with which … Shakespeare discerns the characters of men”

(Low p. 69), and James Anderson commented that Burns’s poetry “charms like the

bewitching though irregular touches of a Shakespeare” (Low, p. 72). William

Pitt, the Prime Minister, remarked to a cabinet colleague “I can think of no

verse since Shakespeare’s which came so sweetly and at once from nature” (Low,

p. 410). Byron applied to Burns a phrase from Thomas Campbell’s Pleasures of

Hope about the patriot-poets who “rival all but Shakespeare’s name below” (Low,

p. 326). Murray Pittock’s essay on Burns’s reputation includes several such

comparisons by major writers or critics.

There have always been dissenters, or at least critics who felt the comparison

might appear asymmetric. Notoriously, at the first Edinburgh performance of John

Home’s play Douglas (1756), a triumphant Scot had drawn lasting ridicule by

shouting out from the pit “Whaur’s your Wullie Shakespeare noo!” (or perhaps

“Weel lads, what think you of Wullie Shakespeare now?”). No one wants to risk

that kind of ridicule. The English critic William Hazlitt wrote that Burns

showed “something of the same magnanimity, directness and unaffected character,”

but that he “is not like Shakespeare in the range of his genius” (Low, p. 297).

Campbell himself disclaimed “any comparison between the genius of the two bards”

(Low, p. 323). Allan Cunningham’s dissent took a different tack, rooted in

national pride. Cunningham wrote that “in ease, fire and passion” Burns was

“second to none save Shakespeare,” but he was anxious to show Burns as a

“thorough Scotchman” who “owes nothing … of the materials of his poetry to other

lands.” Burns read Shakespeare, Cunningham noted, “yet there is nothing of …

Shakespeare about him” (Low, pp. 413, 411).

By the twentieth century fewer and fewer critics risked such comparisons at all.

As Pittock notes, in 1936 the American Burns scholar F. B. Snyder observed that

“No-one today links [Burns’s] name to Shakespeare as eulogists were inclined to

do not long ago” (qtd. in Pittock, p. 34). Nonetheless I was surprised by the

sparseness of modern scholarly discussion. There was no essay about Shakespeare

in the recent collection Burns and Other Poets, and no entry about Shakespeare

in the Burns Encyclopaedia (which has entries for Beattie, Shenstone, and Young,

though none for Milton). In the 120 plus years of the Burns Chronicle, I could

find only one, very old, article with Burns and Shakespeare in the title, about

their portraits, and that turned out only to print the part of the article about

Burns (Keith, 1915). A search for “Burns” and “Shakespeare” through eighty years

of the standard database listing literary scholarship yielded just two items, by

Robert Crawford and Nicola Watson. Both focus on a single aspect of the

comparison, the institutionalization of the Two Bards as national icons or

symbols: Robert Crawford’s essay argues that Burns’s self-identification and

rapid recognition as Scotia’s Bard set the pattern on which Shakespeare too

could be shaped as Bard rather than playwright, and Nicola Watson makes a

similar argument about the recreation of the two poets’ birthplaces as places of

pilgrimage. Comment within books or essays on more general topics is harder to

track down, but two critics seem to me particularly astute, Christopher Ricks in

his book about literary allusion, and Carol McGuirk in her essay on the

aphoristic Burns. But the only recent overview of the topic I have found (and

which I warmly recommend) is a short, lively newspaper article this past January

in the Independent by Gerard Carruthers.

There is abundant evidence that Burns had indeed read Shakespeare extensively.

In the First Commonplace Book, he argues that the study of Shakespeare (or other

poets, or indeed shooting or music or “some heart-dear bony lass”) is at least

as conducive to piety as “bustling and straining after the world’s riches and

honours” (Leask, OERB I:50). The reconstruction of which Shakespeare plays Burns

read rests not only on the survival of individual books that he owned, but on

comments or references in his letters, as cited the index to the Roy Letters,

and allusions or echoes in his poetry, as noted and indexed in Kinsley’s third

volume (cf. Thornton; Robotham; McGinty). When he moved to Ellisland, one of the

first books he wanted to buy was a set of Shakespeare, writing to the Edinburgh

bookseller Peter Hill in April 1789, “I want a Shakespear; let me know what

plays your used copy of Bell’s Shakespear wants” (Letters, I: 391). Bell’s

20-volume Dramatick Works of Will. Shakespeare was a recent publication (in

parts from 1784, in volumes from 1788), and 18 volumes from Burns’s set are

preserved in the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. Burns quotes in his letters

from at least seventeen different Shakespeare plays, more, in fact, than would

be read by the average present-day undergraduate majoring in English, and he

quotes from most of them several times.

Burns was confident enough as a poet to make explicit reference to Shakespeare

even in his first book. In “The Holy Fair,” for example he adapts, Scotticizes,

and footnotes, a phrase from Hamlet: “His talk o’ H-ll … Our vera Sauls does

harrow” (Kinsley, I: 135, line 188: cf. Hamlet, I.v.15). In “A Dream,” he

reminds the notoriously dissolute Prince of Wales that the wild young Prince

Hal, an “unco’ shaver” when roistering with “funny, queer Sir John” in

Shakespeare’s Henry IV, matured to become the hero of Agincourt in Henry V, and

he provides a footnote for those who need reminding that “Sir John” was “Sir

John Falstaff” (Kinsley, I: 268, lines 93-98). It is tempting, perhaps, to think

of such footnotes as window-dressing, a slightly in-your-face assertion of being

well-read. Certainly, they provide a counterpoint to Burns’s 1786 preface asking

readers in judging his poetry to “make every allowance for Education and

Circumstances of Life” (Leask, OERB I: 73). Instead, they should be seen as a

sign of poetic independence, that Burns can without compromising his own voice

make explicit use of so powerful a precursor. What Burns wrote in 1786 about his

relation to his Scottish predecessors Ramsay and Fergusson applies equally to

his use of Shakespeare: he had them “in his eye” or memory, “but rather with a

view to kindle at their flame, than for servile imitation” (Leask, OERB I: 72).

Similar allusions occur in later poems. One of the new poems added in the 1787

Edinburgh edition, “A Winter Night,” not only opens with an epigraph from the

storm or heath scene in Shakespeare’s King Lear, pitying the poor wretches

attempting to defend their “houseless heads” against “seasons such as these”

(Kinsley, I: 303; King Lear, III.iv.32-36), but also quotes Shakespeare later

on, in the lines where the poem pivots from the harshness of the storm to what

Burns argues is the worse harshness of man’s inhumanity to man:

Blow, blow, ye

Winds, with heavier gust!

And freeze, though bitter-biting Frost!

Descend, ye chilly, smothering Snows

Not all your rage, as now united shows

More hard unkindness, unrelenting,

Vengeful malice, unrepenting,

Than heav’n-illumined Man on brother Man bestows! (lines 37-43).

As Kinsley points

out, Burns here is blending together phrases and images from two different

plays, Lear’s speech beginning “Blow windes” that wants the storm to put an end

to “ingratefull Man” (King Lear, III.ii.1-9), and the song in As You Like It

that begins:

\Blow, blow, thou

winter winde,

Thou art not so unkinde, as man’s ingratitude (As You Like It, II.vii, 174-5).

Burns’s use of

Shakespeare was both apposite and confident.

Such examples in the poems could easily be multiplied. Shakespearean allusions

or parallels even occur in Burns’s songs. As Carol McGuirk has pointed out,

behind one of the most famous stanzas in “Scots wha hae” lies a

similarly-structured speech in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, when Brutus asks:

“Who is here so base that would be a bondsman? … Who is here so rude that would

not be a Roman? … Who is here so vile that will not love his country?” (Julius

Caesar, III.ii.31-36). As Prof. McGuirk comments, Burns shifts the language from

formality to direct Scots speech (“Wha will be a traitor-knave? … Wha sae base

as be a Slave?”), but the Shakespearan echo is still clear (McGuirk, pp.

173-174).

For me, the most surprising, and revealing, allusion to Shakespeare was one that

Kinsley missed. I had always thought of Burns’s poem to his first-born child, “A

Poet’s Welcome to his Love-Begotten Child” (Kinsley I: 99-100) as among the most

direct and personal of anything he wrote, genuinely affectionate but also

reflecting some inner conflict. Partly because the Roy Collection has a

manuscript of the poem, I must have read it a hundred times. But Christopher

Ricks has pointed out that, even in so personal a poem, Burns twice echoes and

rewrites phrases from King Lear, both times from the opening scene where

Gloucester talks with Kent about his first-born son, Edmund (“the Bastard”),

whose mother “had a son for her cradle ere she had a husband for her bed” (King

Lear, I.i.15-16: Ricks, pp. 64-65; cf. McGuirk, p. 174 n. 20). Where Burns

writes affectionately,

Welcome, my bonie,

sweet, wee, Dochter!

Tho’ ye come here a wee unsought for; … (lines 13-14),

Gloucester tells Kent

“this knave came somewhat saucily into the world before he was sent for” (ibid.,

22-23), and where Burns addresses the baby as “”Sweet fruit o’ monie a merry

dint” (line 25), Gloucester recalls “there was good sport at his making” (ibid.,

23-24). You can see why Gloucester’s speech would have caught Burns’s attention,

and echoed in his mind when he wrote his own poem on a child that came “into the

warld asklent.“ Gloucester’s dismissive man-to-man bravado encompasses also

admiration and pride, but, partly because of the switch from talking about a

grown son to talking to a baby daughter, Burns’s tone is quite different. The

Shakespearean allusions had become so fully part of Burns’s own imagination, and

so fully integrated with his own language and voice, that till Ricks’s book in

2002 no one had apparently noticed them.

This example is a reminder that Burns’s affinity for Shakespeare began early,

and that it was not something he took in only as he began to interact with

polite Edinburgh society. The submerged echoes from Lear in “A Poet’s Welcome”

occur several years before Burns asks Peter Hill about purchasing a set of

Shakespeare’s works, before Burns had visited the bookshops or drawing rooms of

Edinburgh, even before his first plans to become a published writer. Burns had

been introduced to Shakespeare’s verse as a boy by his tutor John Murdoch.

Unfortunately, Burns’s first reported reaction was negative, and that has

overshadowed Murdoch’s lasting positive effect. The reminiscences of Robert

Burns’s brother Gilbert recount that when Burns was about nine years old:

Murdoch, who was about to leave the area, brought to the cottage at Alloway two

books, an English grammar and a copy of Shakespeare’s gory early tragedy Titus

Andronicus. When Murdoch began to read the play aloud to the Burns family, they

cut off the reading in disgust and distress, so that William Burnes politely

declined the gift, and Robert threatened that if the book were left “he would

burn it” (Currie, I: 61-63).

This well-known incident, however, has obscured Murdoch’s role in Burns’s early

knowledge of Shakespeare. As Burns himself told Dr. Moore in his

“autobiographical letter,” one of his schoolbooks as a boy was Arthur Masson’s A

Collection of English Prose and Verse for the Use of Schools (Edinburgh: Bell,

1767; Letters, I: 135).

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection,

University of South Carolina Libraries.

Murdoch got his

students to learn passages from Masson by heart, and Masson’s anthology had

included seven great Shakespearean speeches. The poetry you learn young and know

well is often the poetry you quote, and playfully misquote, for the rest of your

life. Masson prints in full Jacques’s speech from As You Like It, on the Seven

Ages of Man, beginning “All the world’s a stage” (As You Like It,

II.vii.139-166; Masson, p. 138). In his letter to Mrs. Dunlop on November 24,

1787, Burns first denies, then adapts, and then pours scorn on, Jacques’s

slickly-theatrical opening lines:

Nor do I know any

more than one instance of a Man who fully and truly regards “all the world

as a stage, and all the men and women merely players”; and who, the dancing

bow excepted only values these Players, these Dramatis Personae, who build

Cities, or who rear hedges; who govern provinces, or superintend flocks,

merely as they act their parts (Letters, I: 175).

Masson prints in full

the ousted Cardinal Wolsey’s speech, “A long farewell to all my greatness”

(Henry VIII, III.ii.351-373; Masson, p. 141). Over a four year period, Burns

quotes three different parts from Wolsey’s speech: in April 1786 (“Such is the

state of man: today he buds…then comes a frost,” lines 353-359; Letters, I: 37),

in June 1787 (“he falls like Lucifer, never to hope again,” lines 372-373;

Letters, I:123), and again in March 1789 (“Vain pomp and glory of this world, I

hate you,” line 366; Letters, II:381). Masson prints in full Hamlet’s soliloquy

“To be, or not to be” (Hamlet, III.i.56-90; Masson, p. 139). Burns adapts

phrases from it both playfully in August 1790 (“A consummation devoutly to be

wished,” lines 63-64: Letters, II: 44), and more seriously on his deathbed in

July 1796 (“an illness which has long been about me in all probability will

speedily send me beyond that bourne whence no traveller returns,” lines 79-80;

Letters, II: 387).

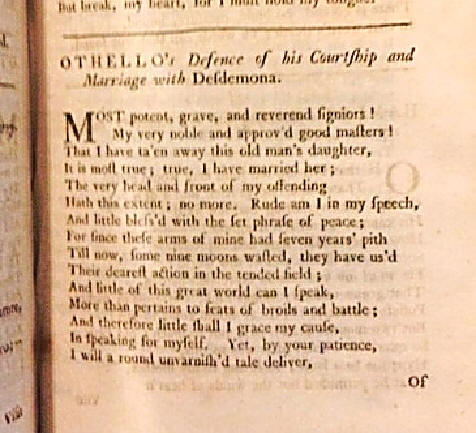

The longest Shakespeare extract in Masson came to have especial significance for

Burns. This is Othello’s defense of his courtship of Desdemona, where Masson ran

together two speeches into one (Othello, I.iii.76-94, 124-170; Masson, pp.

143-145):

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection,

University of South Carolina Libraries.

…Rude am I in my

speech,

And little bless’d with the soft phrase of peace ….

And little of this great world can I speak …

And therefore little shall I grace my cause

In speaking of myself …

I will a round unvarnish’d tale deliver (lines 81-82, 86, 88-90).

Burns clearly

identified with Shakespeare’s picture of Othello as the outsider confronting

Venetian society, rather than seeing Othello primarily as racial victim (but cf.

Crawford, The Bard, pp. 245-246). In January 1787, he used the key lines quoted

above to introduce himself to the Edinburgh bookseller James Sibbald (Letters,

I: 77-78), and in April 1787, writing to Mrs. Dunlop, he uses them again to

explain his omission of polite compliments (Letters, I: 105). But he also

identified with the outsider’s air of danger. In January 1788, he promises

Clarinda he “will make no more ‘hair-breadth ’scapes’” (line 136: Letters I:

204). Later the same month, he uses the same phrase in writing to Margaret

Chalmers (Letters, I: 216). And he quotes it again, in July 1790, in writing to

his old tutor Murdoch (“I have much to tell you of ‘hair-breadth ’scapes i’ th’

imminent deadly breach;’” Letters, II: 38).

In the years after Burns first read Masson, and first took Shakespeare to heart,

he read much more widely in Shakespeare’s works, as the previous examples in

this essay illustrate. But the continuing influence of what he had encountered

in Masson’s Collection indicates how early and how deeply Burns had internalized

Shakespeare’s verse, and how confidently and unselfconsciously he could draw on

it and allude to it, without compromising his own voice.

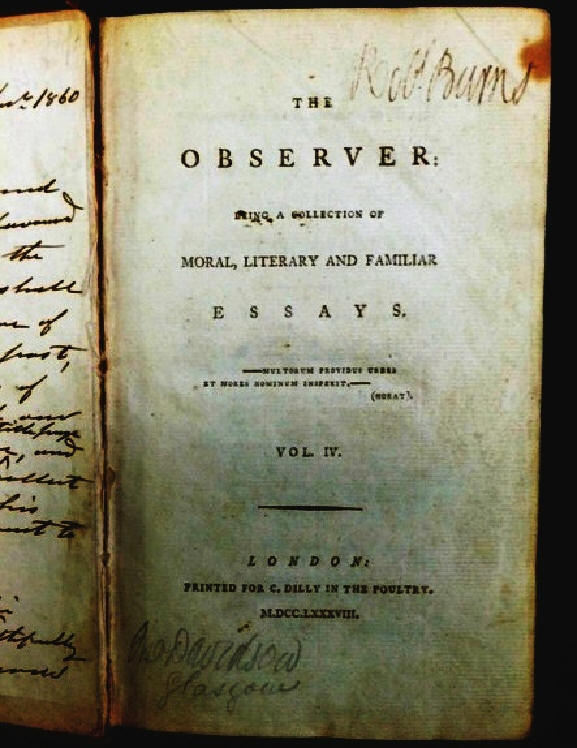

Postscript: One special item in the Roy Collection takes us very close to Burns

as he was reading a passage of Shakespeare. Burns owned a single volume, volume

IV, of Richard Cumberland’s The Observer: being a Collection of Moral, Literary

and Familiar Essays, in its second edition (London: Dilly, 1788-1790: see

Sudduth, p. 16). It had passed from Burns to his son Colonel William Nicol Burns

(1791-1872), and he had given it as a gift in 1860 to the astronomer and

antiquarian Dr. Ebenezer Henderson (1809-1879), of Dunfermline. The book is

signed by Burns on the title-page, and pasted in is a letter from W.N. Burns to

Henderson saying he remembered this book being in his father’s library.

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection,

University of South Carolina Libraries.

Later owners included

a “Jno Davidson,” of Glasgow, and the book was apparently still in private

ownership in 1911, when Duncan M’Naught described it in the Burns Chronicle. It

was sold at auction at Swann Galleries in New York in 1992, and again in 2000,

when Ross Roy bought it. At various points in the book, Burns had marked

passages in pencil or penciled in marginal comments. For instance, against two

passages in an essay on William Cowper (on pp. 17 and 18), Burns has written

“fine;,” against a quotation from a Greek comedian (on p. 102) he has written

“Bombastic,” and against a lengthy quotation from Ben Jonson’s Masque of the

Queens (on p. 146) he has written “Stupid nonsense.” Over the years since

M’Naught described the copy, however, the pencil has rubbed off and some

comments have become difficult to read or illegible. The essay on Jonson had

compared Jonson’s treatment of witches to Shakespeare’s, quoting from both but

without mentioning the source for a lengthy Shakespeare quotation. Burns’s note

against the passage (p. 144) is now very faint, frustrating efforts to get

beyond “Shakespeare [illegible]” for the catalogue description. Because of the

Shakespeare anniversary, John Sawvell, a student working in Rare Books,

photographed the annotation for me.

Image courtesy of the G. Ross Roy Collection,

University of South Carolina Libraries (photo: John Sawvell).

Now, with some

enhancement and some imagination it is just possible to confirm M’Naught’s

reading and to detect, for the first time in over a hundred years, that what

Burns wrote was “Shakespeare Macbeth.” He was making a note for himself of the

Shakespeare play from which the quotation came. The quotation wasn’t hard to

recognize, indeed the annotation may seem unnecessary (after all, how may

Shakespeare plays have witches?), but it is Burns writing Shakespeare’s name,

and precious for that reason.

References

Gerard Carruthers, “Haggis, neeps and soliloquies: the bonds that tie Robert

Burns and Shakespeare,” The Independent, January 25, 2016, online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/haggis-neeps-and-soliloquys-the-bonds-that-tie-robert-burns-and-shakespeare-a6833171.html;

also on line with: The Conversation, January 25 2016, online at:

https://theconversation.com/haggis-neeps-and-soliloquys-the-bonds-that-tie-robert-burns-and-shakespeare-53578

_______________, “Robert Burns and William Shakespeare: Similarities and

Differences,” Celebrate Scotland, January 11, 2016:

https://www.celebrate-scotland.co.uk/articles/burns-night/robert-burns-and-william-shakespeare-similarities-and-differences

Centre for Robert Burns Studies and Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, Two Bards:

Burns & Shakespeare, Annual Burns Conference, Alloway (January 16 2016); at:

http://tinyurl.com/znsg9ve

Robert Crawford, “The Bard: Ossian, Burns, and the Shaping of Shakespeare,” in

Willy Maley and Andrew Murphy, eds., Shakespeare and Scotland (Manchester:

Manchester University Press, 2004), 124-140.

_____________, The Bard: Robert Burns, A Biography (Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 2009).

Richard Cumberland, The Observer: being a Collection of Moral, Literary and

Familiar Essays, 2nd edition, 4 vols. (London: Dilly, 1788-1790).

James Currie, ed., Works of Robert Burns, 4 vols. (London: Cadell and Davies,

1801).

Chris Green, “William Shakespeare vs. Robert Burns: Writers go Head to Head for

the First Time,” The Independent, December 25, 2015:

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/news/william-shakespeare-vs-robert-burns-writers-go-head-to-head-for-first-time-a6786281.html

Arthur Keith, M.D., F.R.S., “An Anthropological Study of Some Portraits of

Shakespeare and of Burns,” Burns Chronicle, ser. 1, 24 (1915): 36-47; a partial

reprint from British Medical Journal, no. 2774 (February 28, 1914), 461-467, and

subsequent correspondence from March 14, March 21, and April 4, pp. 624, 685,

and 793.

James Kinsley, ed., The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, 3 vols. (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1968).

Nigel Leask, ed., Commonplace Books, Tour Journals, and Miscellaneous Prose

[Oxford Edition of Robert Burns, vol. I] (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2014).

Donald A. Low, ed., Robert Burns: the Critical Heritage (London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul, 1974).

J. Walter McGinty, Robert Burns the Book Lover: From Reader to Writer (Kilkerran:

Humming Earth, 2013).

Carol McGuirk, “Burns and Aphorism; or, Poetry into Proverb,” in Sharon Alker,

Leith Davis, and Holly Faith Nelson, eds., Robert Burns and Transatlantic

Culture (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 169-186.

James Mackay, Burnsiana (Ayr: Alloway, 1988).

Pauline Mackay, “Robert Burns Beyond Text: Introducing a New Resource for Robert

Burns Research,” Burns Chronicle (Spring 2011): 42-43.

_____________, “Objects of desire: Robert Burns the 'Man's Man' and material

culture,“ Anglistik, 23:2 (2012): 27-39.

Duncan M’Naught, “Volume Annotated by Burns (Observer, Vol. IX <sic>,

MDCCLXXXVII),” Burns Chronicle, 1st series, 25 (1916): 13-16.

Arthur Masson, A Collection of English Prose and Verse for the Use of Schools

(Edinburgh: Bell, 1767).

Amy Miller, “All Hail! My Own Inspired Bard,” Finding Shakespeare, January 26,

2016:

http://findingshakespeare.co.uk/all-hail-my-own-inspired-bard

Phil Miller, “Shakespeare and Burns: two literary giants to be compared and

contrasted at special conference,” The Herald, January 15, 2016:

http://tinyurl.com/hzuujoy

Murray Pittock, “‘A long farewell to all my greatness’: the history of the

reputation of Burns,” in Murray Pittock, ed., Robert Burns and Global Culture

(Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2011), 25-46.

Christopher Ricks, “The Poet as Heir: Burns,” in his Allusion to the Poets

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 43-82.

John S. Robotham, “The Reading of Robert Burns,” Bulletin of the New York Public

Library, 74:9 (November 1970): 561-576; reprinted in Carol McGuirk, ed.,

Critical Essays on Robert Burns (Boston, MA: G. K. Hall, 1995), 281-297.

G. Ross Roy, ed., The Letters of Robert Burns, 2 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1985).

William Shakespeare, Complete Works, ed. W. J. Craig [Oxford Standard Authors]

(London: Oxford University Press, 1905 etc., repr.1955).

Elizabeth Sudduth, The G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns, An Illustrated

Catalogue (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2009).

Robert Donald Thornton, The Reading of Robert Burns as Reflected in his Letters

and Poems (Unpublished BA honors thesis, Wesleyan University, CT, 1938).

David Trachtenberg and Thomas Keith, Mauchline Ware: A Collector’s Guide

(Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002).

Nicola J. Watson, “Cradles of Genius,” in her The Literary Tourist: Readers and

Places in Romantic & Victorian Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006),

56-89.

|