|

Edited by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Greater Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jurascot@earthlink.net

Dr.

Clark McGinn is nearing the end of his series on the few men who gathered in the

auld Burns cottage to celebrate Robert Burns a few years after his untimely

death. This small meeting became the first Burns Supper, and I doubt any of the

men ever dreamed what they had birthed. Now thousands of Burns Suppers are held

around the world each year on or around January 25th. I have attended

both large and small suppers and have delivered Immortal Memories from the east

coast to the west coast and many places in the South. I say this humbly but with

pride as I do it to honor the Bard. I have read more about Burns and spoken

about him more than any person in my life.

However, before one begins to boast of his or her (yes, her!) Immortal Memories,

let me mention that Clark has flown around the world over eight times delivering

145 Immortal Memories in 30 cities in 15 countries. My dear old Dad, who passed

away in 1953 when I was 14, would have said, “Put that in your pipe and smoke

it!” Clark would never boast of his accomplishments but I will for him. He is

one of the finest Burns speakers I have ever heard. I have always wanted him to

speak at my own Burns Club in Atlanta and hopefully 2016 has a great chance of

being the year my dream comes true. Cross your fingers with me and maybe, just

maybe, this will be the year he comes our way. In the meantime, build yourself a

fire if you can, get a glass of good wine or whatever your choice of drink is,

settle down and enjoy this chapter on NINE MEN: THE BANKER AND THE PROFESSOR.

(FRS: 12.3.15)

NINE MEN: THE BANKER AND THE PROFESSOR.

By Dr Clark McGinn.

For this

chapter in our study of the guest list at the first ever Burns Supper, I want to

look at the intertwined lives of two of the men who attended that memorable day:

David Scott and Dr Thomas Jackson. They shared the friendship and patronage of

Provost John Ballantine and their lives were profoundly influenced by three

local factors: Robert Burns, Ayr Academy and Glasgow University. All subjects

close to my own heart!

We know relatively little about David Scott but we

can assume that he had an enjoyment of poetry and an early interest in Burns as

his name features in the list of subscribers to the First Edinburgh Edition.[i]

Hamilton Paul, in his minute of the first dinner, describes Scott as a ‘banker

in Ayr,’ as at that time Scott was the ‘accountant’, as the senior non-partner

banker was known, in Messrs Hunter & Co. which you will remember was the banking

partnership in Ayr headed by John Ballantine. Some years previously, in that

role, Scott had met the Burns family having been selected as the independent

assessor of John Hamilton of Sundrum’s report into the merits of William Burns’s

counterclaim in the lawsuit brought by the landlord of his Lochlie farm in 1783.[ii]

David Scott appears to have been a trusted colleague of Ballantine’s and as such

he was appointed treasurer of Ayr Academy, one of Provost John’s biggest

projects in the ‘Ayr Enlightenment’.[iii]

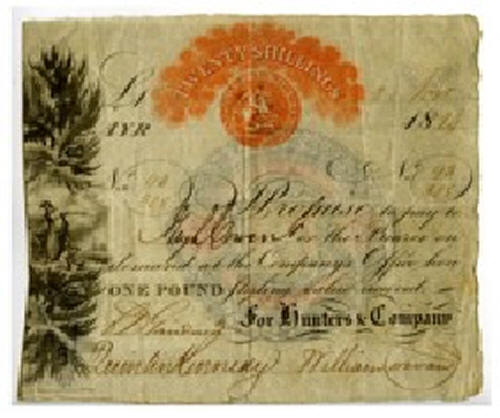

Over time he was to become a full partner of Hunter’s (certainly he was a full

partner by the time the retirement of Hugh Hunter of Pinmore in 1814).[iv]

He died at home in Ayr on 8th June 1823,

at the age of 76.[v]

His executors included Quentin Kennedy of Drumellan (who was Primrose’s son and

heir) and Provost William Cowan of Ayr, both of whom were partners in Hunters

(you can see their signatures on the bank note above) and who were also members

of the Allowa’ Club whose Burns Cottage Suppers were now recognised across

Scotland as annual events.[vi]

I have been able to find very little about Scott’s

family life, save that his only son died in Cartagena on 7 September 1810,[vii]

but the interesting connection for this essay is that his daughter Alison

married Professor William Meikleham of Glasgow University on December 30, 1799.[viii]

Let me take a slight detour and talk of that son-in-law.

Bust of Robert Burns on Ayr Academy Building

William Meikleham was the son of a Kilmarnock

dominie or schoolmaster called William McIlwham (a common, albeit rather

uneuphonious, Ayrshire surname which his son transliterated into some form of

Standard English). He was born in 1771 and went up to study at Glasgow

University between 1788 and 1792. After graduating as a Master of Arts, he

remained at the college and acted as a teaching assistant to the Professor of

Natural Philosophy (Professor John Anderson, one of the great – albeit irascible

– characters in Glasgow’s history. He was the friend of Benjamin Franklin and of

James Watt, and was widely known as ‘Jolly Jack Phosphorus.’ His will created

and endowed the precursor to Glasgow’s second University, now called

Strathclyde.) After Anderson’s death in 1796, Meikleham worked briefly for

Anderson’s successor James Brown (who was too ill, or more likely lazy, to

teach.) At the end of that summer, the first session of John Ballantine’s Ayr

Academy was scheduled to commence, having received its Royal Charter from the

King, and the directors were looking for a man to become the first head teacher,

or Rector as the post is still titled today. The generosity of the donors meant

that the position was offered at an impressive salary of £80 per annum, plus

accommodation and the perks of the job (which amounted to some £20 in boarding

out of town boys and on top of that a skim of the class fees charged by the

masters under him).[ix]

Meikleham was a candidate for this plum position, and approached the opportunity

with an impressive testimonial from his University signed by Principal Davidson

and all twelve professors on the faculty.[x]

William removed from Glasgow to Ayr in the autumn of 1796 to take up his

lucrative new position. When settled in that prosperous West-coast burgh, he met

and married Alison Scott and they would go on to have six children. We will have

cause to talk about the eldest son William Junior, in a moment.

Meanwhile, back in Glasgow, Professor Brown

developed little to no interest in teaching his students the complexities of

Natural Philosophy (as Physics was called in Glasgow until as recently as the

1990s), and he chose Thomas Jackson (our second protagonist) as the new

assistant to replace William and teach his classes while he retained the

emoluments.

Thomas Jackson was born on 16 December 1773 in

Waterhead near Carsphairn

in Dumfries & Galloway and was his father’s eldest son and eponym.

The young Thomas was sent to learn his

letters and sums at Tynon village school and from there, he proceeded to study

at Glasgow. Jackson graduated Master of Arts from there in 1794 and then spent

some time reading Divinity.[xi] He

supported the almost absent Professor Brown for a couple of years until in 1799

Professor Patrick Wilson (then Regius Professor of Astronomy in the

University) was seeking to retire and had chosen to nominate the gifted young

scientist Jackson as his successor. The Chancellor of the University (the Duke

of Montrose) was an arch (not to say rabid) Tory, and so vehemently opposed

Jackson on party political grounds.[xii]

Regius chairs are so called because they were endowed by the Crown who (until a

very few years ago) retained the patronage of appointment through the Government

of the day, However, Jackson had been marked and even a personal appeal by

Professor Wilson to the all-powerful Henry Dundas could overcome the opposition

to Jackson,[xiii]

In a great political fudge, Meikleham (supported by the Tory cabal on the

faculty) was awarded the chair and on his resignation from the Academy its

Whiggish directors wrote to the disappointed Jackson inviting him to fill that

vacancy.

Meikleham was to spend the rest of his life working

and living in the University of Glasgow. In time he transferred from the Regius

Chair of Astronomy to the more senior chair of Natural Philosophy in 1803 which

he held until his death in 1846. While he was not a theoretically distinguished

scientist, he was one of the main teachers of James Thomson, Lord Kelvin, who

remains one of the greatest physicists in history. Beyond his teaching,

Meikleham served in the pivotal position of Clerk of Senate twice from 1802 to

1806 and then again from 1828 to 1831. He briefly entered the Burnsian world

again when was responsible for making the arrangements for Robert Jr. to take up

a Hamilton Bursary in 1801 to come and study at the university upon the

recommendation of ‘Orator Bob’ Aiken.[xiv]

Alison Scott died in 1808 after having borne two

boys, and the Professor married again in 1812 and would have two more sons.

Alison’s sons both went to Glasgow to study – the second child was named David

Scott Meikleham after his maternal grandfather at his birth in 1804. He was an

undergraduate at Glasgow from 1817 for four years until he was appointed to the

prestigious Snell Exhibition at Balliol College in Oxford, where he was awarded

both his BA (Oxon) and MA (Oxon) before returning home to Glasgow to train as a

medic. He emigrated shortly after graduating MD and married one of Thomas

Jefferson’s granddaughters, Septima Randolph in Havana, Cuba where he set up

practice before moving to New York where he died suddenly of malaria in 1849.[xv]

However, his elder brother is of more interest to

this particular story. William Meikleham Junior (born in 1802) graduated MA from

Glasgow in 1820 and then LLB in 1839 after practising as a solicitor in the

city. Through his father’s influence, he acted as legal advisor to the

University and became Clerk of Senate in 1831 in succession to his father.

Unfortunately, he lived a double life and fell into disgrace and bankruptcy in

1845. He had just been re-elected as Clerk but when the accounts of the Hamilton

Bursary were examined, the sum of £3,000 was missing from the trust funds.

William Junior as the trustee had embezzled a significant proportion of the

charity’s capital to finance his lifestyle. He fled justice and died in

Milwaukee in 1852.[xvi]

His father died the following year on 7 May having been in poor health for some

time. That is the history of the rise and fall of the Meikleham Empire in

Glasgow.

Returning to the career of Thomas Jackson, he was

made welcome in the community as the second Rector of Ayr Academy and during his

sojourn in Ayr, with Hamilton Paul, he became one of the two ‘young members’ of

John Ballantine’s Sunday School which was a dining club at Provost John’s home

of Castlehill every Sunday evening after the long day of Kirk services (which,

even for liberal Whigs and New Licht ministers shows a bit of naughtiness in

openly drinking and enjoying oneself on the Sabbath!)[xvii]

However comfortable Jackson’s life was in that

period, and despite his evident success in shaping the life of the Academy, he

had never given up his ambition to hold a professorial chair at one of

Scotland’s ancient universities.[xviii]

In December 1804, the Principal and Professors of the University of St Andrew’s

met to elect a Professor of Natural Philosophy. As you can expect given the

tussle described at Glasgow, this had already been a partisan campaign centred

on political influence and patronage, abut in this case neither side seemed to

have had the leading edge (these stories of university factions and politics of

the time bring to mind the modern novel, The Masters by CP Snow, or the

famous dictum of Dr Henry Kissinger that academic politics is vicious as the

stakes are so small). By the day of the professorial election, two candidates

were front-runners: the eminently suitable Jackson and a Tory placeman called Dr

John Macdonald (a Church of Scotland minister who had not made any study of

Physics and whose only qualification was having the ear of Dundas, still the

Tory patronage ‘King’ of Scotland). At the university meeting the votes were

cast and tied at four all. Principal Playfair claimed the right of exercising a

casting vote as chairman and thus awarded the professorship to Jackson.[xix]

Almost immediately, the Reverend Dr Macdonald obtained an interdict from the

Court of Session in Edinburgh who on judgement overturned Jackson’s nomination

by ruling against the Principal’s ability to count both his substantive and his

casting vote. Not taking that lying down, Jackson and his supporters fought the

case in the House of Lords in London winning on appeal five years later.[xx]

So in 1809, Jackson resigned as Rector of Ayr Academy (his position being filled

by David Ballingall, a fellow member of the Allowa’ Club), packed his

telescopes, instruments and library and set off eastwards to St Andrews for his

instalment. Talking of instalments, Jackson decided to sue the beaten Macdonald

for the salary and fees the latter had taken between 1805 and 1809 while he was

the de facto Professor, but the Court of Session, no doubt peeved by

being overruled at Westminster, ultimately threw out his claim.[xxi]

That was to be the last move in Jackson’s career.

With the exception of a long jaunt to Italy in 1829-30, he sat in the chair of

natural philosophy in St Andrews until his death in 1837. Along the way he was

awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws by his alma mater in 1810,

and was elected to the Royal Society of Edinburgh as a fellow in 1817 and at

some point also to the fellowship of the Royal Astronomical Society. His

teaching at St Andrews was highly regarded, with his only published text book

(other than his contributions to The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia) receiving

special attention, a reviewer calling it ‘one of the best books on elementary

mechanics which our language can boast.’[xxii]

In fact, he seems to have had a reputation as a teacher and scientist who ‘was

highly successful in simplifying the details of abstruse science.’[xxiii]

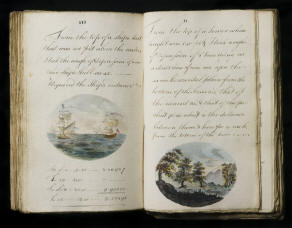

In what seems odd in today’s highly siloed academic world, for several years in

addition to Physics, he taught the undergraduate class in classical Greek too!

Some student notebooks from his courses still exist and the Laing Collection has

a beautifully illustrated note book which he used in his studies.[xxiv]

He died

‘in harness’ as it were, at his home in St Andrew’s on 17 February 1837 in his

64th year.[xxv]

One of his obituaries summed up his character as:

So

averse was he to all superficial pretensions, that, unlike a great proportion of

those who aim at distinction, and do not in reality deserve one-half of the

merit which they claim, or which they get sometimes, the world might safely give

him credit for one-half more of personal worth and intellectual power and

accomplishment, than what appeared in him outwardly. He had the nicest sense of

honour, and the most refined moral delicacy of any man we have ever known, and

withal he possessed such a fund of native good humour, kindliness of

disposition, and urbanity of manners, as rendered him the most agreeable of

companions in private life.

[xxvi]

Which

were characteristics which probably made his an excellent dinner companion for

Hamilton Paul, his father-in-law David Scott and the other six gentlemen of Ayr

on that memorable July day in Burns Cottage.

[i]

Robert Burns,

Poems, Chiefly in The Scottish Dialect, (Edinburgh: William Creech,

1787), p.lx

[ii]

Mackay, Burns, pp.113 -114.

[iii]

For the wider

context, please read Bob Harris, Charles McKean,

The Scottish Town

in the Age of the Enlightenment 1740-1820,

(Edinburgh,

Edinburgh University Press, 2014)

which has a picture of Ballantine’s New Bridge on the cover.

[iv]

London Gazette May

10, 1814, p.990.

[v]

Scots Magazine,

July 1823, p.128.

See also: Will of

David Scott, Banker of Ayr, Ayrshire, National Archives, Kew,

Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury: PROB 11/1676/162.

[vi]

Lloyds Banking Group Archives (Edinburgh):

Reference Number: GB

1830 HUN: Records of

Hunters and Company,

Bankers, Ayr (1657-1854).

[vii]

Edinburgh Annual

Register, 1810,

p.362.

[viii]

Scots Magazine

1799 p.908.

[ix]

John Strawhorn,

750 Years of a Scottish School: Ayr Academy 1233 – 1983, (Ayr:

Alloway Publishing, 1983), p.31.

[x]

Glasgow

University Archives: Papers of Professor William Meikleham: Letter and

certificates recommending William Meikleham as Rector of Ayr Academy

(1796): Reference: GB 0248 DC 056/2/1.

[xi]

James Grierson,

St Andrews As It Was And Is, (Cupar: St Andrew’s University Printer,

1838), pp.222-223.

[xii]

Roger L Emerson,

Academic Patronage in Enlightenment Scotland: Edinburgh, Glasgow and St

Andrew’s, (Edinburgh: EUP, 2008) pp.194-197.

[xiii]

Letter: Patrick Wilson to Viscount Melville, London, 1799. University of

Glasgow Sp Coll MS Murray, 663/18/5.

[xiv]

Anon,

Memorial

Catalogue of the Burns Exhibition Held in the Galleries of the Glasgow

Institute of the Fine Arts From 15th July Till 31st October, 1896,

(Glasgow: W. Hodge, T&R Annan, 1898), p.171.

[xv]

William Innes

Addison, The

Snell Exhibitions from the University of Glasgow to Balliol College,

Oxford, (Glasgow:

MacLehose, 1901), p.106.

Dr Meikleham’s papers are lodged at Special Collections, University of

Virginia Library:

accession Number

4726-c.

[xvi]

Glasgow University

Archives: MS Gen

1717/3/3 - Papers of Duncan MacFarlan (1771-1857) relating to

Meikleham's Case (Hamilton Bursary fraud), 1844-1848.

[xvii]

W&R Chambers Archive, National Library of Scotland, Dep 341, no 517,

Manuscripts of the Rev Hamilton Paul.

[xix]

Scots Magazine,

December 1804, p.969.

[xx]

Playfair and Others vs Macdonald and Others, House of Lord Reports,

26 May 1809.

And while this was wending its way through the legal process, in 1805

Jackson threw his hat into the ring for the Chair of Mathematics at

Edinburgh in 1805, but quickly found he had insufficient patronage at

the Town Council and withdrew.

[xxi]

Jackson vs

Macdonald, Court of Session, Decisions of the Second Division, 5

July 1811

[xxii]

St Andrews University Archives:

GB 227 ms. QC31.J2:

Notes By Henry Ramsay On The Lectures Of Thomas Jackson, 1834-35.

Also, ms.38220,

Notes On Natural Philosophy Taken Down By Alexander Mclaren; Possibly

From Lectures Of Professor Thomas Jackson.

Thomas Jackson, Elements

of Theoretical Mechanics, (Edinburgh: Laing, 1827); Review in The

Repertory of Patent Inventions &c.,vol xxxi, January 1829, at

pp.57-58.

[xxv]

New Statistical Account of Scotland, 15 vols, (Edinburgh &

London: Blackwoods, 1844), vol v: ‘Ayr; Bute; Ayrshire’, Ayr, p.34.

[xxvi]

Ibid.

© Clark McGinn, MMDV

|