|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

One of the most interesting

articles on Robert Burns I have ever read arrived on my desk a few hours

ago. Written by Dr. Patrick Scott (Editor,

Studies in Scottish Literature, & Distinguished Professor of English,

Emeritus at the University of South Carolina), the article presents the

works of global academics and the decision of those involved at the

university to digitize the Studies in Scottish Literature (SSL)

series. It is refreshing to learn that hundreds of articles written over a

half century are now available free of charge online. As a businessman, it

is easy for me to see some risk involved and while some would call it a

gamble, as Dr. Scott says, “it is a gamble in the Ross Roy tradition of

hospitality and openness.” Professor Roy was one of the most open and

transparent men I have ever known. His time was your time and his works were

eagerly shared with all who called on him. If he knew ahead of time, Ross

would do all he could to arrange his schedule to meet you whether you were

acquainted with him or not. I can imagine a smiling Ross as I write this

brief introduction.

The vast majority of universities charge fees for

their scholarly articles or they use a teaser by giving you a half-page or

so to read and then BAM! - the article is discontinued until you pay a fee.

This is not the case at the University of South Carolina which has the

largest collection of Scottish books, including rare books and manuscripts,

outside Scotland. The articles of SSL are yours for the taking so

please, download as many as necessary to meet your needs.

I commend Dean of Libraries Tom McNally, Patrick

Scott, Tony Jarrells, and Elizabeth Suddeth for their banner breaking news.

How refreshing! This is rare and enormously welcomed news in an age where

all of us are tired of being “nickeled and dimed” to death. I believe I knew

Ross well enough to say he would approve. (FRS: 3.25.14)

ROBERT BURNS, OPEN ACCESS,

AND THE DIGITAL STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LITERATURE

By Patrick Scott

Beginning in March 2014, the

whole run of Studies in Scottish Literature, including well over a

hundred scholarly articles about Robert Burns, has been made freely

accessible on the Web. The journal’s URL is:

http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/.

Now that the last remaining

twelve volumes have been added to what had previously been digitized, this

makes available 39 volumes, with over 800 articles and a total of over 7000

pages, published over a period of fifty years (1963-2013). This month also,

for the first time since the first volumes went up in late summer 2012, the

SSL web-site has reached a cumulative total of over 70,000 full-text

article downloads.

Digitizing SSL is

giving us new information about which Burns topics are of the widest

interest, who wants to read about Burns, and how they find the articles

about him. As the success of Robert Burns Lives! has shown, interest

in Burns through the Web is much greater and more widespread than anyone

could have foreseen. The completion of the SSL digitization project

seems a good time to step back and explore what it shows about current

interest in Robert Burns and his writings.

It

is not surprising that Robert Burns has featured prominently in Studies

in Scottish Literature over the past fifty years. SSL was

founded in 1963, and edited till 2007, by the Burns scholar G. Ross Roy

(1924-2013), editor of the standard Letters of Robert Burns, 2 vols.

(Clarendon Press, 1985). In 2007, he had announced that he had edited his

last volume, and that the journal would cease publication, but from the fall

of 2010 he began making plans for it to continue under my editorship (but

see the next paragraph on this), and in July 2012 he transferred all rights

in the journal to the University of South Carolina Libraries, clearing the

way for new volumes and for digitization. It

is not surprising that Robert Burns has featured prominently in Studies

in Scottish Literature over the past fifty years. SSL was

founded in 1963, and edited till 2007, by the Burns scholar G. Ross Roy

(1924-2013), editor of the standard Letters of Robert Burns, 2 vols.

(Clarendon Press, 1985). In 2007, he had announced that he had edited his

last volume, and that the journal would cease publication, but from the fall

of 2010 he began making plans for it to continue under my editorship (but

see the next paragraph on this), and in July 2012 he transferred all rights

in the journal to the University of South Carolina Libraries, clearing the

way for new volumes and for digitization.

For the editorial side, I am

fortunate to have as joint editor Prof. Tony Jarrells, a Walter Scott and

James Hogg scholar in the English Department. Tony’s interest in Scottish

literature dates back to a post-doctoral research assistantship at the

University of Glasgow, and he has also been a visiting fellow at the

University of Edinburgh’s Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities.

Three new volumes have now

been published, both in digital form and in “guid black prent” as paperbacks

available through such on-line vendors as Amazon and Amazon UK. Articles on

Burns in the new volumes have included Stephen Brown’s essay identifying the

original printer of The Merry Muses and Marvin McAllister’s account

of “Scots wha hae” on the antebellum Harlem stage (in SSL 38), and

several reports on Burns manuscripts, including “The Poet’s Welcome” (SSL

38), Burns’s music for “The German Lairdie” (SSL 39), and two on

newly-discovered sources for Burns’s “patriarch” letter to his uncle Samuel

Brown (SSL 38, 39). Digitization lets us include images of each of

the manuscripts being discussed.

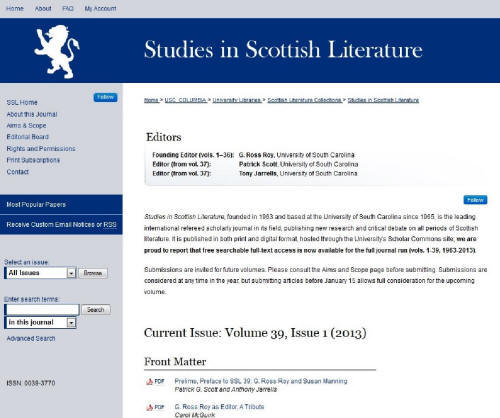

The digital version of SSL

has been mounted in the libraries’ Scholar Commons site, under the

supervision of Chris Hare of Library Systems. The Scholar Commons site is

an “institutional repository,” mounting a variety of papers and articles by

the University’s faculty members in many disciplines. The underlying system

and specialist support are licensed from Berkeley Electronic Press, and

their web designers incorporated SSL’s longtime logo of the Scottish

lion. Studies in Scottish Literature is the most successful journal

based on the University’s site, and month after month tops the statistics

for the most used portion of the site. The first stage of digitization,

reported earlier in Robert Burns Lives! Ch. 153, was funded by the

University Libraries. This new phase, completing digitization of the earlier

volumes, has been supported in part by donations in memory of Ross Roy.

Completing the digital site

is a landmark for us in re-establishing the journal after a five-year gap in

publication. We started by recruiting an expanded editorial advisory board,

and many of these advisors have also written for Robert Burns Lives!.

Previous Burnsian board members Ian Campbell and Ken Simpson agreed to

continue, and new members include such well-known Burns scholars as Carol

McGuirk, Murray Pittock, Gerard Carruthers, and Leith Davis. We have

revived a feature going back to the early years of the journal, when poets

like Tom Scott and Sydney Goodsir Smith argued fiercely (and wittily) about

the nature of Scottish literature. Each of the new volumes opens with a

symposium of short pieces discussing a current issue in the field. The first

symposium, on the Present State and Future(s) of Scottish Literary Studies

(in vol. 38), drew wide attention to the journal’s reemergence and helped

jump-start the relaunch. We are also looking for ways to broaden interest

and rejuvenate the journal through articles that can link Scottish literary

studies with interdisciplinary, international, and other scholarly trends.

But one of the great

strengths of the digital journal is in making available articles published

in the earlier volumes that Ross Roy edited. As my co-editor Tony Jarrells

commented in a recent interview with Craig Brandhorst, “The back issues are

a who’s who of every generation of Scottish scholars. Think of a big person

in the field and you can go back and find his or her articles in one or more

volumes of the journal.” Over the last eighteen months, even before

digitization was complete, the journal has drawn over 72,000 full-text

article downloads. The three new volumes together made up about 10% of

this, with the other 90% coming from previously-published items.

In part, this is because of

the range as well as the quality of the journal’s back volumes.

In Prof. Roy’s words,

Studies in Scottish Literature has always welcomed scholarly articles on

“all aspects of the great Scottish literary heritage.” Since the first

articles were digitized the top twenty-five downloads have included articles

about such authors as Robert Henryson, Allan Ramsay (2 articles in the top

twenty-five), Henry Mackenzie, James Hogg (3), Walter Scott (3), Robert

Louis Stevenson (3), George Douglas Brown, Hugh MacDiarmid (2), Muriel

Spark, Edwin Morgan, Tom Leonard, and Alasdair Gray (2). The bench is deep:

over 230 articles in the journal (more than 40% of the articles originally

mounted) have drawn over 100 downloads apiece. Their variety reflects the

range of Ross’s own literary interests. As I said at Ross’s memorial

service, the amount of use that these earlier articles are getting on the

Web is among the best memorials to Ross Roy himself and the best tribute to

the years of work that he and Lucie Roy put into editing the journal.

Articles about Robert Burns

have played a significant role in building the journal’s reputation. The top

twenty-five downloads include six articles about Robert Burns, and

Burns has been the subject of more contributions to SSL than any

other Scottish author. Over the past fifty years, SSL has included

over 120 items about Burns. The first article wholly about Burns, on “Tam o’

Shanter,” was in October 1963 (volume 1, issue 2), and soon thereafter Ross

Roy used SSL to describe his acquisition of the only copy of the 1799

Merry Muses to have an intact title-page (vol. 2, issue 4). Two

volumes have been largely devoted to Burns: SSL 30 (1998), which

published thirty articles from the Burns Bicentenary conference hosted by

the University of South Carolina in 1996, and SSL 37 (2012), which

published thirteen Burns-related essays in honor of Ross Roy. But aside

from those special volumes, the journal has included over sixty other

articles, notes, and reviews on different aspects of Burns’s writings and

influence; indeed, this count is certainly low because, for Burns-related

book reviews, the way the journal has been digitized only provides separate

entries through 1976, with book-reviews in later volumes being grouped

together.

The Burns articles in SSL

are not only the most numerous category but have also been among the items

most fully used. Full-text downloads of Burns articles to date total nearly

10,700 (about 16% of total downloads), with 3273 total downloads for vol. 30

alone, and 2447 for vol. 37. The most popular Burns articles over this

period have been Peter Zenzinger’s article on Ramsay and Burns (in vol. 30:

651 downloads), Derrick McClure’s study of Burns in Gaelic translation (in

vol. 33: 435 downloads), Corey Andrews on Burns’s poem “Halloween” and

Kirsteen McCue on the air for Burns’s “Red, red, rose” (both in vol. 37: 388

downloads and 336 downloads respectively), the Chinese scholar Yang De-you

writing on Burns’s Russian translator Samuel Marshak (in vol. 22: 361

downloads), and Jeff Ritchie writing on Burns and Wordsworth (again in vol.

30, with 293 downloads, as of March 21).

The article on Burns’s

Russian translator highlights one area in which SSL anticipated more

recent developments in Burns studies. Ross Roy’s own earlier background was

in comparative literature, and among his own earliest research on Burns were

two articles on Burns’s reception in France. He had a special interest in

Burns’s international influence, or what we now call “Global Burns.” Volume

1 included an article on “Robert Burns in Japan,” and over the years this

was followed by articles on “Robert Burns through Russian Eyes” (vol. 2),

“Robert Burns in Hungary” and “Robert Burns’s Danish Translator” (both in

vol. 15), the Marshak article already mentioned (vol. 22), “Robert Burns and

His Readers in China” (vol. 26 ), the reception of Burns in Brazil (vol.

30), and German responses to Burns (vol. 33). This interest in researching

Burns’s status in world literature is also shown by such recent books as

Robert Burns in Global Culture, edited by Murray Pittock and others

(2011), Robert Burns Poetry in Russia and in the Soviet Union, by

Natalia Koh Vid (2011), Robert Burns and Transatlantic Culture,

edited by Sharon Alker and others (2012), The Reception of Robert Burns

in Germany, by Rosemary Ann Selle (2013), and this year The Reception

of Robert Burns in Europe, also edited by Murray Pittock. Several of

these books have been reviewed or noticed on Robert Burns Lives! The

earlier articles now available in the digital SSL complement these

recent studies.

Digitizing SSL not only

allows us to get statistics on how much the articles are used, and which

topics are drawing interest, but also where the interest is coming from.

Interest in Robert Burns is still very international, in perhaps unexpected

ways. Scholar Commons doesn’t track individual users, but it does tell us

about the countries from which they are visiting the site, by tabulating the

differently-tagged internet addresses, IPO’s, for each site-search; an ipo

is the standard suffix (.uk, .fr, .de., etc.) at the end of non-U.S.

web-addresses. This table illustrates the ten countries from which most

searches came, after the United States:

TABLE I:

WHERE SSL’S USERS COME FROM

(referrals

for non-US users only, September 2012-September 2013, by ISO country tag)

Searches have been recorded

that originated in over 120 different countries, but it is worth noting that

the top ten countries are not only those with traditional Scottish links.

Canada and Australia are there (with New Zealand also scoring well), and

some of the European countries with longstanding Scottish ties such as

Germany, France and Italy also post good totals, but that the top ten

includes Russia, India and Turkey.

The Scholar Commons system

also allows us to track how researchers discovered the articles in

Studies in Scottish Literature. Before digitization, a student would

look up an author or topic in a specialized bibliography, find there was an

article in SSL, and then hope the nearest library had the right

journal volume on the shelf. Both the bibliographies and the journals have

long been available in digital form, but often only to subscribers or

through university sites with access restricted to students and faculty.

From the beginning, SSL has been indexed in the standard MLA

International Bibliography, the gold standard for literature research,

and its articles can still be located that way. However, with the decision

to make SSL freely available on the Web (“open-access”), like

Robert Burns Lives!, articles in the journal are discovered much more

easily. The majority of those who now use the site come to an article

directly, rather than through a bibliography or a library web-site or even

through the journal’s own home-page. Indeed, as the chart below

illustrates, only a sixth of referrals to SSL from outside the

University come through the journal’s own site or related Scholar Commons

listings, while three quarters of users find SSL articles through a

Google-related site, either Google itself, or the more specialized Google

Scholar.

TABLE II:

HOW SSL’S USERS FIND THE SITE

(referrals

from external sites, Sept. 2012-Sept. 2013, by domain)

The journal’s own home-page

has a search box on the left of the page, and this is often the surest way

to find specific articles from SSL, particularly articles on

individual works or if you already know the article’s author or the main

words in the title. But links to most articles can be also found just as

easily by simple keyword searches in Google and Google Scholar. Though a

Google search may bring up many thousands of possibilities, articles from

SSL, especially on specific literary works, often come up on the first

or second page of the search results, and this brings them to the attention

of many users who never visit the larger journal site.

Finally, a word about Open

Access. The Scholar Commons site would have allowed us to charge a

subscription for access, either to all volumes, or to the most recent ones,

but we took the decision early on that, as long as we can do so, we would

make the digital journal free, just as the libraries that own them have

traditionally given free access to the print volumes. SSL doesn’t

carry advertising, and unlike scientific journals (and PLOS) we don’t charge

our contributors a per-page fee to publish their work. For the time being

the libraries and individuals who purchase the print version through Amazon

are the journal’s sole (and quite modest) funding stream.

Most research on Burns, like

most research in the humanities generally, is done without special grants or

funding, but when a university-based scholar does get a grant toward

research expenses, it is increasingly common for the grant agency to require

that the resulting research be made free to the public. In the U.S., much

publicly-funded scientific and medical research is mounted on the PLOS (the

Public Library of Science, started in 2003) or another open-access site,

BioMedCentral. Over 450 scholarly organizations have now signed on to the

Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and

Humanities, and the European Union requires time-delayed open-access on all

the research it funds. In 2013, the U.K. government and its Research

Councils proposed new regulations mandating free access, immediately or

after a stated time-lapse, for grant-funded research (and, in effect, all

major research projects in British universities). Whichever way the

Referendum goes, most Scottish scholars expect similar open-access policies

to apply to their work. These requirements have been much criticized, both

by some learned societies and, especially, by the journal publishing

industry, but “it’s coming yet, for a’ that.” SSL is well positioned

to help Scottish literature scholars meet this growing expectation.

After three new volumes, we

think we’ve shown that the journal is fully re-established. So far, we are

the only major refereed scholarly journal in Scottish literary studies that

meets the grant agencies’ open access requirement, and in time that should

bring us some first rate contributions from a new generation of Burns

scholars. Like Robert Burns Lives!, and the Glasgow-based on-line

magazine The Bottle Imp (sponsored by the Association for Scottish

Literary Studies), we’ve found it exhilarating to make this body of literary

research free and accessible to readers that traditional journal publication

often shuts out. It’s a gamble, but it’s a gamble in the Ross Roy tradition

of hospitality and openness, and I like to think that it’s a decision that

Burns would have approved. Even if his vision of worldwide brotherhood

could hardly anticipate the World Wide Web, the widespread availability of

small printing-shops in late 18th century Scotland meant that

many of Burns’s own poems and songs were so widely distributed as to be, in

effect, Open Access almost from the start.

References

Berlin Declaration on Open

Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities

(Max Planck Institut, October 22, 2003):

http://openaccess.mpg.de/286432/Berlin-Declaration

Brandhorst, Craig. “Return of

the Scottish Journal,” USC Times (Dec. 4, 2013):

http://tinyurl.com/nm9r6lg

RCUK Policy and Guidance on Open Access

(Research Councils UK, March 6, 2013):

http://www.hefce.ac.uk/whatwedo/rsrch/rinfrastruct/oa/

McGuirk, Carol, “G. Ross Roy

as Editor, A Tribute,” Studies in Scottish Literature, 39 (2013):

xi-xvi:

http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol39/iss1/2/

“The Present State and

Future(s) of Scottish Literary Studies,” Studies in Scottish Literature,

38 (2012): 3-48:

http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol38/iss1/

--contributions by Murray

Pittock, Gerard Carruthers, Leith Davis, Matthew Wickman, Willy Maley, and

Caroline McCracken-Flesher, and the editors

Scott, Patrick, “The New

Studies in Scottish Literature Goes Digital (and Keeps Print),”

Robert Burns Lives! 153 (September 20, 2012):

http://www.electricscotland.com/familytree/frank/burns_lives153.htm

|