|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Just over two years ago, Ross

Roy and I began discussing a very important matter to him. He wanted to tell

the story of his grandfather, W. Ormiston Roy, and he wanted his narrative

to be shared within the pages of Robert Burns Lives!. His logic, as always,

was simple and to the point. He wanted his account put on the Internet so it

would be available to people for years to come. Ross wanted to share with

the world his story about a most remarkable man and one that any Scottish

journal would be honored to print, and so am I!

In our many conversations, mostly about Burns, rare books about Burns, eBay,

new books on Burns, our Burnsian friends, etc., Ross would inevitably

mention something about his grandfather. He enjoyed telling me of the

influence his grandfather had on him and he liked sharing stories of their

trip to Scotland together when Ross was an eight-year-old lad. More than

likely he would briefly smile or his eyes would sparkle when talking abut

his grandfather. There was never any doubt of the admiration, respect and

love Ross had for his grandfather. Having never known either of my

grandfathers, or grandmothers for that matter, I was always impressed and in

awe of the close relationship of these two men.

In this introduction, I’d like to pay tribute to several sources in the

preparation of this article beginning with Ross’s own typing of notes on his

old electric IBM memory typewriter. It is especially noteworthy to mention

that this is one of Ross’s last writings before his untimely death. Patrick

Scott mentioned in an email to me recently that this article was “long

promised to you”. When Ross reached the point where typing became a chore,

he began dictating his thoughts to Ms Sej Harman, renowned for her outstanding

work in Studies in Scottish Literature. The story went through several

additional revisions and was still unfinished at the time of Ross’s death.

Soon after, Patrick Scott pitched in to complete the editing. Patrick also

added the quotation from Ormiston Roy’s essay about Burns and supplied

further biographical details. I’m particularly indebted to Ross’s dear wife,

Lucie, for her permission to share Ross’s story with our readers. All

illustrations are from the Roy Collection at the University of South

Carolina. My deepest thanks to one and all! (FRS: 5.23.13)

W. Ormiston Roy as Remembered by his

Grandson

by G. Ross Roy

It was through my

grandfather, W. Ormiston Roy (1874-1958), a landscape gardener,

horticulturalist, and book collector, that I first became acquainted with

Robert Burns. My relationship with him spread over twenty-six years, from

the early nineteen-thirties, to the late nineteen-fifties, and what follows

is not a formal biography, but my memories of him during those years with

some background information about him added about his career and his

interest in Burns.

William Ormiston Roy was born

in Montreal in 1878 and spent all of his life there. He was proud to share

a birthday with Winston Churchill; they exchanged letters, and like

Churchill he was photographed by the famous Canadian photographer Yousuf

Karsh. Though friends called him Willie, he signed himself W. Ormiston Roy;

he told me that initially he had used William O. Roy, but that people began

calling him Mr. O’Roy, thinking that he was Irish. So he began to use the

more formal signature (abbreviated below to WOR). One of thirteen children,

he was obliged to go to work when his father, a gardener, died. He joined

the staff of the Mount Royal Cemetery, Montreal’s Protestant burying ground,

where he remained throughout his working career.

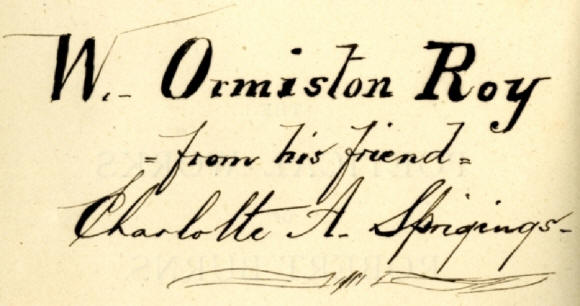

In 1892, he married Charlotte

Sprigings, daughter of the cemetery’s Superintendent. Among the books that

I later inherited was one of her first gifts to him, before they were

married, for Christmas 1890. This was a volume of Burns inscribed to her

“friend” Ormiston Roy. .

My grandmother’s inscription, Christmas 1890

They had five children, but

only three reached maturity. When his father-in-law died, WOR became

Superintendent. Early in life, he became interested in landscape

architecture, and he transformed the Mount Royal Cemetery into one of North

America’s most beautiful cemeteries. In this, he was influenced by the

ideas of the Boston landscape architect H.W. Sargent and his cousin the

botanist Charles Sprague Sargent. He was also a firm believer in cremation,

and arranged to have Canada’s first crematorium built. To mark the Mount

Royal Cemetery’s 150th anniversary, the cemetery and McGill-Queens

University Press issued a very attractive book about its history, in which

William Ormiston Roy plays a prominent role.

Probably based, in part, on

what he had done to the Mount Royal Cemetery, WOR began to develop a

landscape business with private clients and businesses, taking on outside

consulting commissions. But he never founded his own company, always

working as an independent. Among other clients, he worked for the Prime

Minister of Canada, Henry Lyon Mackenzie King, for the nature writer (and

Whitman enthusiast) John Burroughs in upstate New York, and on Henry Ford’s

property at Dearborn, Michigan. Rather than take a fee from Ford, WOR had

an agreement that when he was in Great Britain, which he visited annually,

the Ford Company would supply him with a car and driver.

This is where I come into the

story. In 1932, when I was eight years old, my grandfather asked my parents

if they would allow him to take me along with him to Great Britain. They

agreed, and this trip started a relationship which lasted until his death in

1958. One of the highlights of the trip for a boy was being allowed, in

Stirling, to hold in his hand William Wallace’s sword—it was much too heavy

for me to brandish. It was on this trip that WOR purchased Robert Burns’s

wooden porridge bowl, now in the Roy Collection (see

http://www.electricscotland.com/familytree/frank/burns_lives69.htm for a

photograph and description).

My grandfather knew several

of the leading writers and poets in Scotland, and so at an early age I

received an introduction to current Scottish literature and developed what

has remained a continuing interest of mine to this day. One visit was to the

Scots-language poet Charles Murray, author of Hamewith (1900), which

includes his poem “Gin I was God,” where God looks down at humanity and

decides to start again. (Mrs. Murray took one look at me and said, “That

boy hasn’t washed behind his ears since he left Canada,” whereupon I was

whisked into the Murrays’ bathroom and thoroughly scrubbed.) During the

trip, I was made to memorize several contemporary Scottish poems which I had

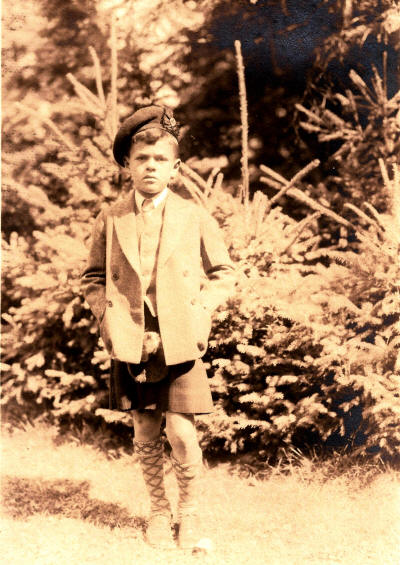

to recite later when I returned home. I was also outfitted with a tweed

jacket and kilt which I unwillingly wore back home on special occasions.

G. Ross Roy, ca. 1932

I recall that we spent

several days at Queensferry Inn, and I enjoyed going down to the wharf to

see the ferry come and go. Although he never told me so, I think that my

grandfather tired somewhat of the constantly questioning eight-year-old, and

he took me down to London to stay with Aunt Annie. We were distantly

related, and she too had worked for the Mount Royal Cemetery, moving to

London upon retirement. She was a gentle soul and went to great pains to

entertain me. All things come to an end, however, and my grandfather and I

sailed from Southampton to New York and home to Montreal.

It was on trips to Scotland

such as this that WOR got to know many of the leading Burnsians of the

interwar period, including John McVie, then secretary of the Burns

Federation, and Duncan M’Naught. In the later 1930s, he was one of those

involved in trying to help the German Burns scholar Hans Hecht when he had

been deprived of his professorship at Gottingen by the Nazis and came to

Scotland as a political refugee.

WOR was a person of wide

interests. He bred collie dogs and once won best of show at New York’s

Westminster Kennel Club, the most important American show. He won trophies

at the winter sport of curling. He also won the Banks Medal from the Royal

Horticultural Society at Kew Gardens in London.

W. Ormiston Roy in mid-life

As a landscape architect, or

“landscape Naturalist” as he liked to call himself, he had an intimate

knowledge of trees, shrubs and flowers. In the 1920s he started planting

peonies, and in 1927 or 1928 my father joined him. He had extensive fields

in the Montreal area as well as farms in Champlain, NY, and Uniontown,

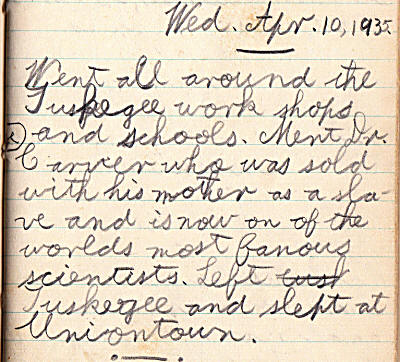

Alabama. In 1935, he took my sister Anne and me with him down to Uniontown

when he went to oversee the harvesting of the peonies. I was allowed to

leave school for an extended period provided I kept a diary. I still have

the diary, and it makes interesting browsing. For instance, I met the

agricultural scientist Dr. George Washington Carver, of Tuskegee, famous for

encouraging the growth of peanuts and the uses of peanut butter.

Diary entry about meeting Dr. George Washington

Carver, 1935

During my school years, I

lived with my parents, moving with them out to the suburbs of Montreal. When

I returned to university, after war service as a Navigator in the Royal

Canadian Air Force, on loan to the Royal Air Force, I was faced each day

with a train ride, followed by a streetcar ride and then a bus ride. My

grandfather lived walking distance from the university, and by then had lost

his wife, my grandmother, so I moved in with him. In exchange for driving

him, he let me use his car. The driving was really very pleasant because

WOR had taken to visiting the Gaspé area in the summer to escape ragweed.

We usually stayed in the houses of fishermen-farmers. We would go out for a

day in one of the small fishing boats. Most of the catch was then dried on

racks. WOR mixed easily and we soon became almost residents of the various

villages in which we stayed. I learned a valuable lesson from him—how to

associate with people of all classes.

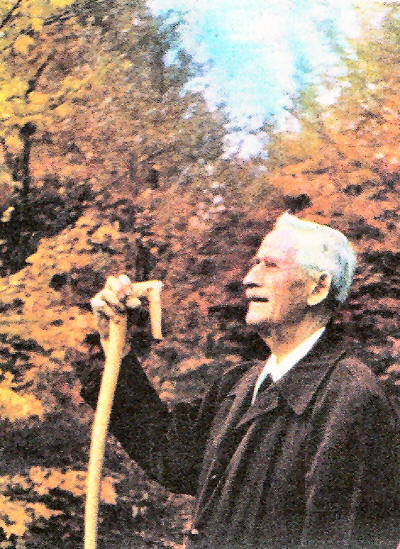

W. Ormiston Roy in later life

We both did our own cooking;

mine was just ordinary food. WOR lived on a self-imposed odd diet composed

of “healthful” meals. He scornfully claimed I was “digging my grave with my

teeth.” Ironically, I am now older than he was when he died.

Although he pretended to mock

me for attending university, he was proud of me, and spoke highly of me to

others when I was not around. He liked to quote Burns on a college

education when the bard said of those who went to “college-classes” that

they “gang in stirks [bullocks] and come out asses.”

WOR collected books on a

variety of topics, and it was from him and a couple of other people that I

learned how to collect as well as the joy of the chase. But he not only

collected books, he read them. At mealtime and when I was driving him we

very frequently discussed literature. This was a new experience to me.

Both my parents read and my maternal grandmother had quite a large library,

but to them reading was a personal activity, not discussed with others. And

so when I moved in with my grandfather, I entered a whole new world.

WOR preferred poetry to

prose, and this was reflected in his collecting, although there would have

been plenty of room for fiction in his large house. He was not particularly

fond of Shakespeare, although he had a set of Hamilton Wright Marbie’s

eleven-volume Shakespeare, which I still have. I cannot tell which, if any,

of the plays he read because none of the volumes is marked. In other

instances, WOR annotated books he owned, usually at the back. These

comments make fascinating reading, showing a keen intellect at work.

Soon after I moved in, the

topic turned to Robert Burns and as long as I was with WOR the conversation

constantly included references to the poet. My grandfather knew Burns and

could quote him at will. He once told me that he had never had an

experience in life for which he was unable to find an appropriate quotation

from Burns. And so for several years, I was regaled by sometimes very witty

quotations from the poet. I also helped him find books to add to his

collection. By then, WOR was elderly, so I usually visited the bookshops on

my own, but I was happy to have my grandfather pay for books I found.

Unlike many Burnsians, WOR

could claim that in forty years he had never given a talk about Burns. His

only surviving written comments about the poet are a short typescript from

after World War II, explicitly influenced by William Stewart’s pre-World War

I book on the same topic, in which WOR praises Burns as the first poet to

discover the importance of the Common People:

“This is part of the real

abiding service which Burns rendered to humanity. He saw them as no one else

had ever seen them; as they had not even seen themselves. He was the first

to say “:A man’s a man for a’ that”--...What a discovery! The power of man!

Compared to this, the explosion of an atom bomb appears like a noisy stunt.

“While there is no poet—who

is so truly a national poet, yet there is none who has done so much to break

down national boundaries and destroy racial antipathies....In these days,

all kinds of people seek to associate themselves with the name of Robert

Burns, but no opponent of liberty—no traitor to democracy has the right to

claim that Burns is on his side.”

One could not be with Willie

without some of this infectious enthusiasm rubbing off, and before long I

became interested in Robert Burns. Two-thirds of a century have elapsed but

the interest has not waned. When I was accepted at the University of Paris

(Sorbonne) I proposed a thesis on Burns but was told that there was already

one—Auguste Angellier’s. And so my academic interest in Burns was put on

hold.

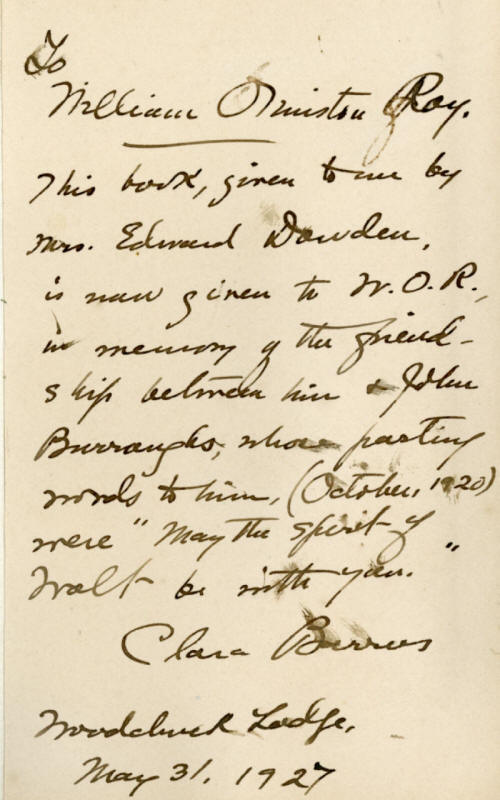

WOR also collected the poetry

of Walt Whitman, and when I took a degree at Strasbourg, I included Walt

Whitman in my thesis. At this point my grandfather gave me a volume of

Whitman, the “Birthday Edition” from 1889, which the poet had inscribed to

the critic Edward Dowden and which had been reinscribed owner by owner till

it came to WOR. It is a lovely book, now housed in the University of South

Carolina.

The Birthday edition of Whitman’s Leaves of

Grass, inscribed to WOR

My grandfather had a

considerable library which reflected his interests. Naturally Burns played

a major role in the collection. He told me that he purchased a Kilmarnock

edition in 1939 for ₤100. He sent it to a Burns expert for verification.

Meanwhile World War II broke out and he had to leave for home as rapidly as

possible, without the Kilmarnock. Some time after 1939 he tried to contact

the person to whom he had sent the volume. Unfortunately the man had died,

and the family treated WOR like a charlatan who was trying to make off with

a prized book. He was dead before I bought my copy to replace it.

While in Strasbourg I met

Lucie Jehl, and we were married there in 1954. My parents had been in an

automobile accident and my father was unable to travel. In order to have a

family member there, my grandfather agreed to come over, and he served as my

witness in the civil wedding which had to precede a religious wedding in

France. When Lucie and I left Strasbourg and moved to Montreal, we saw my

grandfather quite frequently. He had specially liked Lucie’s cheese soufflé,

and he would check she was going to cook it before inviting himself over for

dinner.

In 1956 we returned to France

for me to work on my doctorate at the Sorbonne. WOR came over to Europe to

attend the first meeting of the Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome.

He was very interested in drying food for shipment to underprivileged

countries, and he talked up his idea to the FAO delegates. While in Europe,

he visited in Strasbourg for a couple of days, and when he went to the

station to catch his train for Paris, Lucie and I went along to the

station. We parted with a handshake. Nothing was said, but somehow we both

knew that we would not meet again. I returned to my in-laws and wept.

WOR died in 1958. Lucie,

Madeleine and I were already on our way home to Canada when a telegraph

reached me telling me this. I believe that he was trying to hold out until

I arrived. Those present when he passed away told me that the last word

that he uttered was my name.

My grandfather left a

considerable estate which went to his two living children—my uncle William

Wallace and my father Archibald Carlyle. The one item treated differently

from the general estate was his library, which he left to me.

The different groups of

books, sometimes very large, were divided up and dispersed in various ways.

An important group of horticultural volumes was gifted to the Montreal

Botanical Garden. I kept the general literature for myself. But the

collection was still too large, so I held an auction among graduate students

and donated the proceeds to the Cancer Society, because that was the disease

from which WOR had died.

What interested me most in

what I had inherited was the Scottish literature, particularly the Burns

books. One could say that the Roy Collection began in 1958, with that

inheritance, but I date the collection’s beginning back to 1890, when my

grandmother gave WOR the book previously mentioned. Even though I had

helped WOR build it, I was astonished by the collection of which I had

become the proud owner. Several packages containing books purchased by WOR

when he was over for my wedding had not even been opened. There was of

course no longer a Kilmarnock edition, but I believe there were already

seven 1787 editions.

Slowly I began to sort

through the material. This was not an easy task because in 1958, before

Egerer’s Burns bibliography, there was no comprehensive guide to identifying

Burns editions and no way of knowing exactly what had been printed. Partly

for reasons of space, I sold my own collection of Canadian literature and

used the proceeds to buy a Kilmarnock to replace the one he had lost. Today

Kilmarnocks rarely come up for sale, but in 1961 when I wanted one, I wrote

to three Scottish dealers and was offered two by return mail. I paid a good

deal more than the ₤100 my grandfather had paid, but far less than the

selling price of a Kilmarnock today. I have gone on adding to the

collection, which is now six or more times bigger than the one I inherited.

I like to think back on the

things I have done with WOR and the gifts I have had from him, going from

the eight-year-old boy walking the deck of a steamer to that last handshake

at the railway station in Strasbourg. Of all the gifts my grandfather gave

me over a long life, the greatest was his love. Many years later, after I

transferred the Burns collection to the University of South Carolina, Lucie

and I established a W. Ormiston Roy Visiting Fellowship named for him for

scholars to come and work on Burns. Later still, as the frontispiece in the

published catalogue to the Burns collection, I chose the Karsh portrait of

my grandfather.

W. Ormiston Roy, by Yousuf Karsh

|