|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

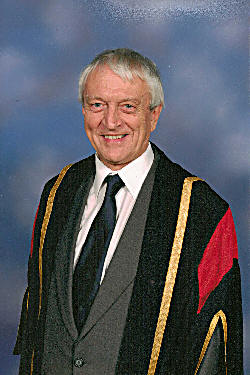

I met Dr.

Walter McGinty last month at the annual conference hosted by the Centre for

Robert Burns Studies at the University of Glasgow. I knew immediately I was

talking to a man who loved and revered Burns as a scholar and Burnsian.

Below is an article written by Dr. McGinty along with some biographical

information regarding his life which you will find just as interesting as

his article. Enjoy! (FRS: 2.14.13)

* * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Born and

brought up in Glasgow, Scotland. Educated in local schools and on leaving

secondary school, aged sixteen. My education was hugely disrupted by the

second World War. The only certificate I had was the one from the Robert

Burns Federation! I worked as an apprentice accountant and auditor.

Later, I felt

drawn to the Ministry of the Church of Scotland, and after struggling to get

Highers at Night School, studied Arts and Divinity at the University of

Glasgow and Trinity College. After an assistantship in Glasgow I spent

thirty-five years as a Parish Minister. In three quite different Parishes: a

coal-mining community near Falkirk, the small town of Alloa, then at Alloway,

the birthplace of Robert Burns for the last twenty years before retiring. A

life long interest in Scottish History and Literature was further stimulated

by the lively Burns scene in Ayrshire. During my Alloa ministry, in

1975 I gained a B.A. in History with the Open University. Whilst in Alloway, I

became interested in the amazingly varied and extensive reading of Burns,

and as a hobby, started trying to read all the books he had read. The hobby

became more, when I was asked to do a Ph.D at the University of Strathclyde.

I was still working at Alloway, but managed to complete it in four and a

half years, graduating in 1995 with the thesis:

Literary, Philosophical and Theological

Influences on Robert Burns'. It was based on the simple idea of

reading the books that Burns had read, and trying to ascertain what

influence they had upon his life and work. Although all the time I was in

the ministry I was writing sermons and addresses on a regular basis, I did

not make any attempt to write for publication. That all started after

retirement. Since then I have published:

Through a Glass Brightly, Alloway's

Stained Glass, (Alloway,1999);

New and Revised Through a Glass Brightly

Alloway's Stained Glass (Alloway, 2006)

Robert Burns and Religion

(Aldershot and Burlington, 2003)

‘“An

Animated Son of Liberty' A Life of John Witherspoon,

Arena Books

(Bury St Edmunds, 2012)

Papers

in Studies in Scottish Literature:

John Goldie and Robert Burns Vol. XXIX

Milton's Satan and Burns's Auld Nick Vol XXXIII

My work as a

minister led me to being involved in the wider world of education. I spent

five years as a Lay-Governor of a Teacher Training College in Ayr, and

twelve years as a Lay-Governor at the then University of Paisley which in

time became the University of the West of Scotland. It was during my spell

at Paisley, that I became aware of the connection between Paisley and

Princeton through John Witherspoon. It was the proposal to erect a identical

statues to him on both campuses that began my interest in him and that

resulted in my latest book, research for which started in 2002. In 2005, I

spent a month incarcerated in the Rare Books section of the Firestone

library of Princeton University, examining the Witherspoon Archives and also

was privileged to use the beautifully appointed Witherspoon Room in the

Princeton Public Library and to do some work in the Princeton Historical

Society.

I have four

sons by my first marriage, and my wife Lois and I have now been together for

nearly fourteen years.

Aspects of the Humour of Robert Burns.

Dr. J. Walter McGinty

The humour

displayed in the poems of Robert Burns, relates to an ancient tradition of

Scottish writing that makes use of physicality and the grotesque. The roots

of this humour can be traced through the work of William Dunbar in the 15th

century writing ‘On his Heid-ake’, and Sir David Lindsay in the 16th century

using a gallows scene as a source of fun, in ‘The Thrie Estatis’. Burns’s

contemporary, Tobias Smollett, continued within this tradition. Burns

recorded his admiration of the novelist for ‘his incomparable humour’ 1.

Burns draws upon this tradition, and with his own input, based on a generous

assessment of human nature, his humour ranges widely, through the physical,

and the grotesque of poems such as ‘Halloween’ and ‘Tam o’ Shanter’, and

‘Sic a wife as Willie’s wife’, to the gentle poking fun at the clergy in

‘The Holy Tulzie’, or the wry between-the-lines humour of ‘The Twa Dogs’, or

the pauky irreverence of his ‘Address to the Deil’.

One of Burns’s

best known poems demonstrates this willingness to make any occasion an

opportunity for humorous observation.

‘To A Louse, On

seeing one on a Lady's bonnet at Church’

HA! Whare ye

gaun, ye crowlin ferlie!

Your impudence protects you sairly:

I canna say but ye strunt rarely,

Owre gawze and lace;

On sic a place.

Ye ugly,

creepen, blastet wonner,

Detested, shun’d, by saunt an' sinner,

How daur ye set your fit upon her,

Sae fine a Lady!

Gae somewhere else and seek your dinner,

On some poor body.

Then my own

favourite verse:

O Jenny

dinna toss your head,

An’ set your beauties a’ abread!

Ye little ken what cursed speed

The blastie’s makin!

Thae winks and finger-ends, I dread,

Are notice takin!

And then from

this unlikely subject comes the marvellous punch-line:

O wad some

Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

It wad frae monie a blunder free us

An’ foolish notion:

What airs in dress an’ gait wad lea'e us,

And ev’n Devotion! 2

It is this

willingness to see the humour that can be found in any situation that led

Burns into his comments on some of the Ministers that he came across, and

sometimes on the religion they claimed to confess. He once said, ‘Of all

nonsense, religious nonsense is the worst’. 3 So when Burns turns

his humour upon Ministers, he has a field day.

During the

controversy over the publication of William McGill’s book, A Practical

Essay on the Death of Jesus Christ, 4 Burns wrote ‘The Kirk's

Alarm’, or to use its final title, ‘The Kirk of Scotland's Garland - A New

Song’, a poem that featured a number of the committee who were investigating

McGill’s alleged heresy.

Burns told Mrs

Dunlop what he hoped to achieve by the poem: ‘If I should fail of rendering

some of the Doctor's foes ridiculous, I shall at least gratify my resentment

in his behalf. 5 These words were written on 17th July 1789, just

two days after the Presbytery appointed its committee. It is indicative of

how closely Burns followed the case, that, in the first draft of the poem,

he writes verses on nine out of the fifteen ministers who were on the

Committee. His humorous comment is not gratuitous abuse, but accurate and

informed comment made on the basis of a personal knowledge of each one of

them.

He sets the

scene in the opening two verses:

ORTHODOX,

Orthodox, who believe in John Knox,

Let me sound an alarm to your conscience;

A heretic blast has been blawn i’ the West -

That what is not Sense must be Nonsense, Orthodox,

That what is not sense must be Nonsense. - 6

Then referring

to McGill, he mocks those who condemn him for preaching the faith in

accordance with logic and common sense:

Doctor Mac,

Doctor Mac, ye should streek on a rack,

To strike Evildoers with terror;

To join FAITH and SENSE upon any pretence

Was heretic, damnable error, &c

Then comes his

lovely pen-portrait of the much respected Dr William Dalrymple, the minister

who baptised Burns, and who, it was hinted at by some, was just as guilty of

heresy as McGill. Mrs Dunlop said of this verse, that even Joshua Reynolds,

couldn’t have drawn a more accurate portrait:

D’rymple mild,

D’rymple mild, tho’ your heart's like a child,

And your life like the new-driven snaw;

Yet that winna save ye, auld Satan maun have ye,

For preaching that three’s ane and twa, &c.

Burns, then

with biting satirical humour, turns on those who attacked McGill. First is

the Rev. John Russel, of Kilmarnock, who had started the heresy hunt off

with a sermon against McGill's book. On another occasion Burns had referred

to Russel as ‘Hell-mouthing John Russel’ 7:

Rumble John,

Rumble John, mount the steps with a groan,

Cry, the BOOK is with heresy cramm’d;

Then lug out your ladle, deal brimstone like aidle,

And roar ev’ry note o' the D-MN’D, &c.

‘Aidle’, by the

way, is cow's urine, so Burns is saying that the threats of fire and

brimstone ladled out by Russel, are as of little value as animal waste.

Russel was a

minister who was weighted down with the seriousness of man’s condition. He

had a big voice and a thunderous delivery, and had featured in an earlier

poem, ‘The Holy Fair’, as, ‘Black Russel’ and as, ‘the Lord's ain trumpet’

8

Burns is very

deliberately choosing his words. He is not so much trying to be clever, as

to be relevant to the subject. A good example of this is when he deals with

the Rev. David Grant, the Convener of the Presbytery's committee

investigating McGill. On another occasion he referred to Grant as the priest

of Ochiltree – ‘a designing, rotten-hearted Puritan’. 9 ‘In the

Kirk of Scotland's Garland – a new song’, he writes:

Davie Rant,

Davie Rant, wi’ a face like a saunt,

And a heart that would poison a hog;

Raise an impudent roar, like a breaker lea-shore,

Or the Kirk will be tint in a bog, &c.

In the existing

manuscripts of the poem, there are a further couple of variant verses, both

of which display a similar low opinion of this man. David Grant in 1778 had

been Clerk to a committee that was responsible for circulating a petition to

alert people against the Government's intention to pass a bill for Roman

Catholic Emancipation. On that same committee was Lord George Gordon, later

known as ‘Mad Lord George Gordon’. Gordon incited riots in Edinburgh in

1778, and two years later in London, where he led a mob in protest at the

proposed passing of the Bill. Here's one of the variations:

Pauky Clark to

George Gordon—gi’e the Doctor a Cord-on,

And to grape for witch marks—gi’e it o'er;

If ye pass for a Saint, it’s a sign, we maun grant,

That there's few gentlemen i’ the cor’. 10

Burns, however,

reserves his most virulent comments for the Reverend William Peebles,

Minister of Newton-on-Ayr, and Presbytery Clerk of Ayr. He had been

extremely active in the whole process against McGill, and five years later,

when in 1791 the General Assembly finally threw the matter out of court, he

remained a bitter enemy, but this time, not just against McGill, but against

Robert Burns. He nursed his anger for the next 20 years and in 1811

published the most violently anti Burns book I’ve ever read.

11

Burns wrote of

Peebles:

Poet Willie,

Poet Willie, gi’e the Doctor a volley

Wi’ your ‘liberty’s chain’ and your wit:

O'er Pegasus' side ye ne'er laid a stride,

Ye only stood by where he sh—, &c. 12

Burns’s words

are understood when you know what he knew about William Peebles. On 5th

November 1788, the one hundredth anniversary of the Glorious Revolution,

Peebles preached, and later, published a sermon accusing McGill of writing

things that were incompatible with his calling as a Minister of the Church

of Scotland. In that same publication, he included a poem that celebrated

the Anniversary. Here are the first and last verses:

Hail, liberty,

celestial maid!

To ev’ry free-born Briton dear,

In beauteous robes of light array’d,

With all thy radiant train appear:

To thee, on this auspicious day

We raise the votive, solemn lay;

Smit with thy charms—thy energy divine,

The wond’ring nations ’round in one vast chorus join.

—

Britain thy

winding shores along

Let the glad voice of praise arise;

Thy verdant vales repeat the sound

Thy cities waft it to the skies.

May sons unborn prolong the lay,

And oft proclaim this glorious day

And, bound in LIBERTY’s endearing chain,

May latest ages hail RELIGION’s blissful reign!

13

Burns might

have taken Peebles to task for his dull clichéd lines, but instead he chose

to highlight three things: He refers to Pegasus, which is the horse of the

poetic muse. and implies that Peebles has never mounted that horse, but has

only stood at its rear, ‘the place where he shit’. He is no poet. In quoting

Peebles’s ‘LIBERTY’s endearing chain’, Burns mocks this incongruous

metaphor. In passing, Burns makes reference to Peebles’s ‘wit’. There could

hardly have been a man who had less wit. In a sermon, Peebles once said,

‘True joy is a serious thing’. 14

Several years

before all this, Burns had judged Peebles to be a shallow man. In a poem,

the ‘Holy Tulzie’ which is about a dispute between two ministers in the

Presbytery over parish boundaries, Burns makes reference to the preaching

qualities of several ministers:

O ye wha tent

the Gospel-fauld

Thee, Duncan deep, and Peebles shaul. 15

When Peebles’s

sermons are looked at in detail, that shallowness of thought emerges. His

exegetical methods are simplistic. He pays no attention to context, and

sometimes makes the text fit to a theological theory. Such a theology is not

derived from a mind that seeks openly to discover what the Old and

New Testaments are trying to say to us about God, but comes from a mind

that is already made up as to what they are saying. Burns, on the other hand

had been exploring theologians like

John Taylor of

Norwich and John Goldie of Kilmarnock, who urged that in examining any text,

due attention should be paid to its context, allowance should be made for

the time in which it was written, and above all, that we should be willing

to acknowledge that scripture need not be taken literally, but can be

interpreted figuratively. 16 The words that Burns uses to

describe various preachers mark him out as a ‘sermon taster’. He had

listened with a discerning ear and his judgements were based on experience.

As I come to

the end of this discourse on the humour of Burns, I want to go back to the

theme with which I started, when I asserted that Burns’s humour ranged from

the gentle to the coarse.

One of Burns’s

favourite novelists was Laurence Sterne whose famous character, Tristram

Shandy, Burns called his bosom companion. Sterne’s humour is markedly gentle

and slow burning. The opening sentence of Sterne’s novel, The Life and

Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, begins with a

dissertation on Tristram’s conception that lasts to the end of the chapter:

I

wish either my father or my mother, or indeed both of them, for they were in

duty both equally bound to it, had minded what they were about when they

begot me. 17

He then goes on

to meditate on the consequences that must have inevitably followed, when

after his father had gone to bed and begun the proceedings of begetting, his

mother had interrupted him by asking, ‘Have you not forgot to wind up the

clock?’

Robert Burns

was drawn to Sterne because they both were happy to exercise their humour in

their work. Sterne once wrote:

Great Apollo if

thou art in a giving humour. Give me. I ask no more, one stroke of native

humour, with a single spark of my own fire along with it.

18

Burns made the

same prayer when he wrote, ‘A random shot of countra wit is a’ I ask’,

19 and he asked that, in the very same spirit of Laurence Sterne’s, ‘I

ask no more’.

In Robert Burns

we see the wit of the country of his birth, a country whose traditional

humour was of the earth, full of physicality and every aspect of our human

nature, and now and again with just a touch of the grotesque. Burns was

sometimes harsh, sometimes coarse, but more often, gentle, as befits the man

who urged:

Then gently

scan your brother Man,

Still gentler sister Woman;

Tho’ they may gang a kennin wrang,

To step aside is human. 20

References and Notes

Quotations from

Robert Burns are taken from:

The Poems and

Songs of Robert Burns

edited by James Kinsley, 3vols. (Oxford, 1968), and

J. De Lancey

Ferguson’s The Letters of Robert Burns, 2 vols. second edition edited

by G. Ross Roy (Oxford, 1985).

1. Letters I, 296, to Mr Peter Hill, 18th July

1788.

2. Poems I, 193, 194.

3. Letters II, 146, to Mr Alexander Cunningham, 10th

September 1792.

4. William McGill, A Practical Essay on the Death of Jesus Christ,

(Edinburgh, 1786).

5. Letters I, 422, to Mrs Dunlop, 17th July 1789.

6. Poems I, 470-474, ‘The Kirk of Scotland’s Garland – a new

song’.

7. Letters I, 94, to James Dalrymple, Esq. of Orangefield,

February 1787.

8. Poems I, 135, ‘The Holy Fair’.

9. Letters I, 465, to Lady Elizabeth Cunningham, 23rd

December 1789.

10. Poems I, 473, in a footnote.

11. William Peebles, Burnomania: The Celebrity of Robert

Burns considered in a Discourse addressed to all real Christians of every

denomination to which are added Epistles in Verse, reflecting Peter Pindar,

Burns &c. (Edinburgh, 1811). [Note: originally published anonymously].

12. Poems I, 474, ‘The Kirk of Scotland’s Garland – a new

song’.

13. Included in the volume: A Sermon by the Rev. William Peebles

preached to the Magistrates and Council of the Burgh of Newton upon Ayr, 5th

November 1788 (Kilmarnock, 1788).

14. William Peebles, Sermons on Various Subjects (Edinburgh,

1794).

15. Poems I, 72, ‘The Holy Tulzie’.

16. John Taylor, The Scripture Doctrine of Original Sin (1741);

John Goldie, Essays on Various Important Subjects Moral and Divine

(1779).

17. Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy,

Gentleman, p.1 (In the Penguin Classics edition p.35). First published

1759-1767.

18. Tristram Shandy, p. 193.

19. Poems I, 179, 182.

20. Poems I, 53, ‘Address to the Unco Guid, or the Rigidly

Righteous’. |