|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

This is the 150th article on

Robert Burns Lives! and little did I realize what had been set in motion

when the first chapter appeared in The Family Tree publication out of

Moultrie, Georgia with a circulation of over 75,000 subscriptions. Sadly

that marvelous paper ran into financial trouble and went out of business. It

was then, however, that Robert Burns Lives! moved to the internet site of

www.electricscotland.com.

What began as an outreach to

Burns laymen like me changed directions because of one man. In a short time

our web site evolved into both an academic and layman presentation.

Originally the Burns web site was not my focus as I was then reviewing books

under the title of A Highlander and His Books. Doing both meant fewer

articles on Burns, so I made the decision to cut back drastically on the

book reviews and concentrate primarily on Robert Burns. Doing so has been

such a fun trip! Much joy has come my way through meeting people whose names

I only knew on the spines of books they wrote or edited. Many are now my

friends, and as time or conferences allow, we find time to break bread or

share a bottle of wine.

The one man I credit with

giving Robert Burns Lives! its new emphasis is Professor G. Ross Roy from

the University of South Carolina. This man, recognized as a world-class

Burns scholar, is one of the finest writers in the world dedicated to

scholarly research of Burns. He was even once referred to as the “Chairman

of the Bard” by Edinburgh columnist Jim Gilchrist. No one in the Burns

community is more respected than Dr. Roy. His affair with Burns began on a

trip to Scotland with his grandfather when Ross was only eight years old. He

is an easy man to admire and is a grand gentleman who was fortunate to marry

a young French girl named Lucie. Both have become close personal friends of

Susan and mine. I credit his article titled Important Editions of Robert

Burns (Chapter 6 in our Index and later expanded on in Chapter 13) as the

turning point in our emphasis on Burns. I like to think that Robert Burns

Lives! is a different type web site since there are so many excellent

contributors writing on numerous areas of the Burns mystic.

While corresponding back and

forth in several emails with Dr. Patrick Scott, also from the University of

South Carolina, he shed some light on the article below by saying that it

“is about a Burns puzzle—some jotted numbers in Burns’s handwriting where

there is no immediate clue about what the numbers represent. Soon after he

got the letter on which they are written, Ross Roy published his solution to

their meaning, in his journal Studies in Scottish Literature. The account

below is his recent updating of that article, for readers of Robert Burns

Lives! “

Reaching our 150th chapter is

a milestone for Robert Burns Lives! and I wanted this one to be a special

article by a special person, thus we give you another commentary by G. Ross

Roy. Thank you, Ross, for helping make Robert Burns Lives! what it is today.

(FRS: 8.29.12)

How Many Copies Were

Printed of Burns's Second (Edinburgh) Edition?

By G. Ross Roy

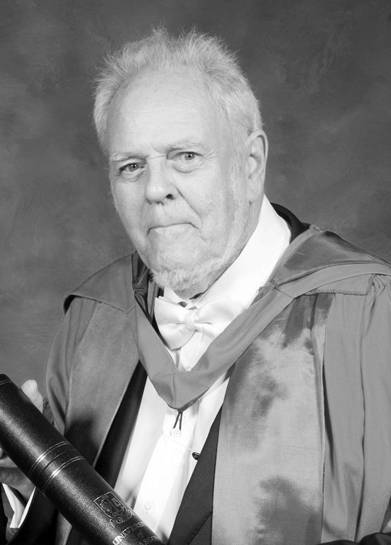

G. Ross Roy receiving his honorary Doctor of

Letters

from the University of Glasgow, June 2009

Ross Roy celebrating his 88th birthday

Carol Benfield and Ross Roy enjoying his

birthday festivities

Thanks to Kathy Dowell, University of South Carolina Libraries for the above

two pictures.

We know from Burns's

correspondence that the second or Edinburgh edition of his poems, sold by,

but not published by, William Creech in 1787, attracted more subscribers

than anticipated. In a letter to Mrs. Dunlop of 22 March 1787, the poet

mentions a "third" edition because "the second was begun with too small a

number of copies.--The whole I have printed is three thousand" (Letters of

Robert Burns, ed. Roy, Oxford 1985, II: 90).

The two groups of copies

printed in Edinburgh that Burns calls here the second and third editions are

the so-called "skinking" and "stinking" versions, well known to

bibliographers and collectors. The misprint of “stinking” for “skinking” in

Burns’s “Address to the Haggis” (on p. 263) is only one of several small

variants. All the variants occur in the first part of the book. Because the

decision to print extra copies was made mid-way through production, only the

first sections of the book (up to p. 288) required resetting the type; all

the sheets for the later sections (pp. 289-368), including both the original

and the extra copies, were printed from the same type-setting. Copies made

up of sheets from both print runs were apparently published at the same

time, on 17 April 1787. To modern Burns scholars, the “skinking” and

“stinking” versions are known as the first and second states of the second

edition, and the term “third edition” is reserved for the London edition

later that same year.

For want of more precise

information it has been assumed that there were 1,500 copies printed of each

state. Of this number about 2,900 were subscribed for, including 500 copies

for Creech. J.W. Egerer argues in his Bibliography of Robert Burns

(Edinburgh, 1964: pp. 12-17) that Creech had difficulty disposing of his 500

copies and that he sent some of them to London, where they were sold by A.

Strahan and T. Cadell before their London edition of 1787 appeared. All of

the numbers which Egerer and earlier scholars suggest are approximations.

A closer approximation may be

inferred from some jottings on a letter of 13 February [1788] from Henry

Mackenzie to Burns. The manuscript of the letter, formerly in my personal

collection, is now [2012] in the G. Ross Roy Collection at the University of

South Carolina Library. What Mackenzie wrote was published from this

manuscript in Prof. Horst Drescher’s Literary Correspondence and Notebooks

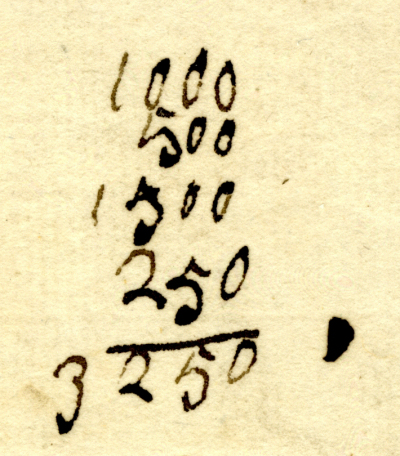

of Henry Mackenzie (1989), pp. 153-154. As the image below shows, on a blank

section of the letter the poet has jotted down the following figures in a

column: 1000, 500, 1500, 250, added up to a total of 3250.

No Burns scholar who has

examined the manuscript doubts that the figures are in Burns’s handwriting.

This total suggests that this may have been Burns's calculation of the

number of copies printed. The 1000 would have been the additional names

which came in on the subscription lists, the 500 the copies subscribed for

by Creech, the 1500 the initial printing (the "skinking" variant), and,

perhaps, the 250 the number of copies to be sent to London.

There is no proof that these

numbers had anything to do with the print run of Burns's poems, but no other

solution comes to mind. Certainly it could not refer to any sum of money;

Burns never made that much in his life. That 250 copies were planned on for

the London market would fit in with Egerer's conclusion that copies were

sent there before the London edition could be printed, and would also

suggest that Creech's estimate that he could sell 500 copies in the

Edinburgh market was not far off the mark. |