|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

A few months ago, three men

came together in Scotland at a seminar in Greenock’s Lyle Kirk to talk about

Highland Mary. Two of them were from Scotland and the third made his way

from Columbia, South Carolina to appear on the program. This octogenarian,

on a previous visit to the Greenock Burns Club, had promised he would

return, and G. Ross Roy keeps his word. Speeches by the other two, Gerry

Carruthers and Kenneth Simpson, have already been posted on Robert Burns

Lives! and can be found in the index as Chapters 128 and 148

respectively. Today it is an honor to bring you Professor Roy’s paper.

Colin Hunter McQueen, Ross’s dear friend, read his paper to the assembled

crowd. (You will also find in Robert Burns Lives! a book review of a

publication by Colin and his son Douglas under Chapter 33.)

The Greenock seminar has

been described as a major conference on Burns, and with these three speakers

participating, it couldn’t have been anything else. They delighted club

members and guests with their remarks, and I only wish I had been there to

enjoy the occasion as well. You will find more information about the seminar

on the Greenock Burns Club website. A big thank-you to Ross Roy for allowing

our readers to have access to his presentation.

With these three articles

about Highland Mary, I am proud to say this is the second subject within the

web site on which we have had three different articles. The other topic was

on Robert Burns and Slavery. (FRS: 7.25.12)

As Others Saw Him: Robert Burns and

Highland Mary

By G.

Ross Roy

April 2012

(Note: Ross

Roy's talk discusses how some important non-English speaking Burnsians

presented Burns and Highland Mary, beginning with the German scholar

Hans Hect, and then looking in more depth at the major French Burns

translators and scholars. He ends with brief comment on work in some

other languages.)

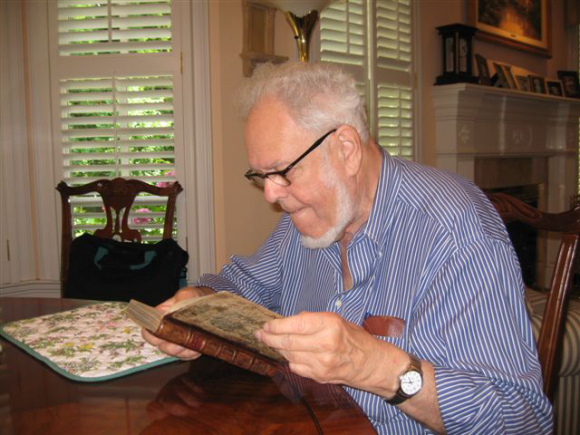

Ross Roy studying a Kilmarnock

HANS HECHT

There have been more

editions of German translations of Burns than into any other language, and

the only foreign book on Burns which has been translated into English and

which went into a second edition was Hans Hecht’s ROBERT BURNS THE MAN AND

HIS WORK. The German original work was published in 1919, and the English

translation by Jane Lymburn in 1935, with a new Preface by Hecht. In it he

points out

We all know that too close

proximity obscures the vision, and that too great love blinds the judgment

as much as too violent antipathy. In the case of Burns there is the further

difficulty that the controversial points move along the dangerous lines of

sexuality, alcoholism, religion, politics, and class prejudices or

preferences.

Hecht was himself the victim

of prejudice and was in the 1930s obliged to give up his position at the

University of Göttingen and move to Switzerland. It may also explain why

this excellent volume did not go into a second edition in German.

Hecht sometimes gets carried

away in describing events. For instance, when he mentions how James Armour

destroyed the paper he had given Jean, effectively a marriage certificate,

Hecht says that the poet went “stark, staring mad” and he goes on to say

that Burns “felt himself nine-tenths ready for Bedlam” (p. 85). I have read

numerous accounts, including Burns’s own, of the Armour event, and nothing

suggests what Hecht claims. Immediately after this passage Hecht introduces

Highland Mary. In Hecht’s words

The woman with whom Burns

sought and found consolation for the insult he had suffered was, according

to a firmly rooted sentimental tradition, Mary Campbell, the Highland

lassie, the never-forgotten immortal sweetheart, the transfigured love,

lover of the song “Thou Lingering Star,” written in the autumn of 1789 (p.

86).

It strikes me that here it

is Hecht who overdoes the sentimentality rather than Burns.

But who was this Mary

Campbell? As this audience will know, we have little to go on, and, of

course, Hecht admits to the obscurity of this woman. In a rather fanciful

passage Hecht contrasts Jean Armour and Mary Campbell.

Hecht has a problem with

various earlier sources about Highland Mary, whom he almost always refers to

as Mary Campbell. These sources, he writes, do not bring us any nearer to

the facts which Burns may have intentionally concealed. Mary Campbell, about

whose existence it is not permissible to doubt, remains herself and in her

real or her imaginary relationship to Burns a shadowy female figure which

glided through the life of the passionate poet during this period, and whose

death later became to him the subject of melancholy memories. That is all.

The star that ruled the hour was named Jean, not Mary. (pp. 87-8).

With these words Hecht

finished off Highland Mary. Hecht is a respected critic, but he does not

appear to have understood what Burns wrote, and perhaps failed to write

about a woman whom Burns really did love, and about whose death he really

grieved. Unfortunately German readers will have been misled about a woman

who played an important, if brief role in the life of the poet.

All told Hans Hecht gave his

readers a balanced picture of Scotia’s Bard, but as far as the works, the

warmth and passion Burns poured into his poetry and his life, both the

readers and Highland Mary are the losers.

Second only to German

translations of Burns are those into French. These two languages were

chosen because there are more translations of Burns into German than into

any other language. And French was chosen because Auguste Angellier’s study

of the poet is by wide odds the most important foreign-language work on

Burns.

LÉON DE WAILLY

Léon de Wailly produced the

first volume of French translations of works from Scots into French. The

title COMPLETE POEMS is far from accurate because the volume contains only

181 numbered items and a smaller selection unnumbered. By 1843 there

were a good few well known works of Burns, but the selection was a very

respectable one. No major poem appears to have been omitted with one major

exception; there were no bawdy poems from THE MERRY MUSES OF CALEDONIA

included in his selection. But this is true also of the two other nineteenth

century French works on Burns which, it will be noted, contained no such

material. There was probably more risqué and outright pornographic material

printed in France at the time than there was in the UK. But such material

was disposed through a thriving sub-culture, rather than openly.

De Wailly divides his book

into four sections. First there is an introductory life of Burns, followed

by poems published in Burns’s lifetime, then there is a section of songs,

numbered (181 of them in all), and finally posthumous poems. The chronology

of when the poems and songs were written is ignored, and there does not

appear to be a subject grouping of the works included.

In translating poetry there

are three methods available: create as accurate a prose version as possible;

recreate the poetic pattern of each stanza accurately as possible,

but without rhyme; finally, recreate the rhyme itself. De Wailly opted for

the third solution. I know exactly how de Wailly felt, because I once

translated a French Petrarchan sonnet into an English Shakespearian sonnet.

I never tried to repeat the task.

Early in his introduction de

Wailly claims that the major problem Burns had in getting his life together

was love. While “love begotten” children certainly complicated the poet’s

life, there were other problems aplenty.

In recounting the life of

Burns, de Wailly waxes almost poetic in tempering condemnation with

admiration. He quotes at length from Burns’s long autobiographical letter to

Dr. John Moore, the source of much of our knowledge of the poet’s early

life, which was first published in 1800. It should be remembered, however,

that there is an element of self-justification in Burns’s letter too.

Unfortunately, de Wailly

does not indicate that the letter is by no means complete as quoted. And of

course Burns cannot always be relied upon when speaking about himself.

Writing on his own behalf, de Wailly claims that a poet should be judged

more as a human being than as a poet. This does not mean that de Wailly was

downgrading the craft of poesy, because he wrote of himself that if he “had

the honor” he would wish to be judged that way. Did this opinion have any

influence on the order in which the poems were to be placed? I have looked

over this order several times without coming to a conclusion. But if the

order is a subjective decision, then assessing this judgment is subjective

also. Put briefly, if the creative process is subjective, then surely the

judgmental process is equally subjective. A great poet will know

instinctively when he has the right word or phrase. In a manuscript of one

of Keats’s great odes the poet has crossed out several trials, always

settling for the best. But that, too, is a subjective statement.

Coming to the Highland Mary

poems translated and arranged by de Wailly, the first such is “Flow Gently

Sweet Afton,” which, oddly, de Wailly entitles simply “Afton.” The

translation is accurate and the words flow along smoothly, although de

Wailly can not capture the almost magical touch Burns gives to the evocation

of that gently-flowing stream which is told not disturb the wondrous dream

Burns imagines his Mary is having.

When Jean Armour’s father

mutilated the declaration of marriage Burns had given her, which would have

been considered a legally binding document at the time, Burns turned his

attention elsewhere. Mary Campbell, universally known as Highland Mary,

caught his fancy and the two decided to emigrate to Jamaica, where the poet

would have had employment as an overseer of field hands. I need not dwell

upon the sad story of Highland Mary’s trip to her family to bid them adieu,

and her death in Greenock where she lies buried.

The pineapple was an exotic

fruit in eighteenth-century Scotland and it is quite likely that Burns had

never seen one, let alone tasted it. Anyway, the poet exhibits little

knowledge of the fruit in his poem inviting Mary to accompany him to the

Indies where he writes: “O sweet grows the lime and the orange / And the

apple on the pine;” but de Wailly had a better knowledge of botany because

he correctly identifies the fruit as a pineapple. And of course by 1843

probably the pineapple was more firmly established in Paris than it was over

a half a century earlier in rural Scotland. Burns wrote the poem when, after

his rift with Jean Armor he had decided to take employment in Jamaica. In

fact the poem can be seen as a plaintive meditation by the poet about his

own upcoming separation from his beloved native land. De Wailly handles the

plaintiveness well without becoming maudlin. One point I did find odd in his

translation: he addresses Mary as “vous.” Surely a woman whom he was

inviting to go with him abroad, and who might even be carrying his child,

would be addressed with the familiar “tu.”

One of the most beautiful

poems of loss and longing that Burns wrote was “Thou Lingering Star,” which

is the third Highland Mary poem, written about three years after the

melancholy event of the death of Highland Mary, at a time when Burns was

happily established with Jean. The poem certainly underlines the fact that

Burns was genuinely in love with Mary and was heart-broken at her loss. One

may be permitted to wonder if Burns ever showed the poem to his wife. If I

may digress, I am the proud and fortunate owner of a Meters silhouette of

Clarinda with, encased at the rear, a lock of hair. This must be Clarinda’s

because it would be unimaginable that anyone would place a lock of someone

else’s hair there. There are three or four other such lockets in existence,

none with hair. In a rather steamy letter to Clarinda, Sylvander promises

that the locket will be hung next to his heart. One may suppose that

Clarinda’s silhouette was discretely removed at times.

RICHARD DE LA MADELAINE

Following de Wailly’s

translation Richard de la Madelaine produced a small collection of

twenty-six poems by Burns in prose translation; it was published in 1874 in

Paris. The decision to use prose allowed de la Madelaine to strive for

greater accuracy but at a price, and it brings to mind Gustave Flaubert’s

acid comment that a translation, if it is beautiful it is not faithful; if

it is faithful, it is not beautiful. Unfortunately this prose translation

tends to bear out Flaubert’s statement.

De la Madelaine’s

arrangement is strange. The translator begins with a 35-page introductory

essay in which he notes that this is the land of Douglas, Wallace, Robert

Bruce, Adam Smith, Dugald Stewart, and Sir Walter Scott, but goes on to say

that it is not necessary to visit a country to appreciate its literature.

I’m not at all certain why Smith got in, but the selection was de la

Madelaine’s selection, not mine. Most of the remainder of the introduction

appears to be given over to showing the reader how much de la Madelaine knew

and sheds little information on Scotland, let alone Burns. One major

informative part comes when Burns’s famous autobiographical letter to Dr.

John Moore is quoted—for five entire pages. Drawing on almost half a century

of editing experience I would have had de la Madelaine eliminate all but

about five pages of the Introduction and have made the compiler rewrite

those pages. But let us now turn to the selections themselves.

To give listeners an idea of

the cultural level of de la Madelaine’s discourse he wrote the following in

this treatise: “We are no longer discussing Shakespeare’s plays, abominable

pieces, worthy of the savages of Canada.” Had de la Madelaine troubled to

visit Canada he would have discovered that the natives had a rich, but

unwritten, cultural life.

Turning to the poems, for no

discernible reason the first three in this collection are poems Burns wrote

to Highland Mary, although de la Madelaine never mentioned her in his

introduction. The first of the Highland Mary songs to appear is “Flow Gently

Sweet Afton,” simply called “Afton” here. (The other love song which

appears in this collection is “The Blue-Eyed Lassie,” which was written

about Jean Jaffray.) No prose rendition can catch the rhythm of this

“murmuring stream” of course.

The second Highland Mary

poem is entitled just that: “Highland Mary” (I translate). It is preceded by

a short note on Mary Campbell, whereas there was no introductory note to

“Flow Gently.” It is an almost morbid work centering around Burns’s

memories of Mary Campbell after her death in 1786. The poem was first

published in Scots Magazine May 1798. In the poem the poet speaks of

how pale are the “rosy lips I aft hae kiss’d sae fondly” and goes on to say

that her “mouldering …heart that lo’ed me dearly.” One can wonder why de la

Madelaine chose that poem, certainly not one of the poet’s best.

De la Madelaine’s third

translation is “To Mary in Heaven,” which again deals with Highland Mary’s

demise, but in a much more dignified way. Here the translator notes the

date of its composition and the fact that Mary had been greatly loved by the

poet. However, this final poem, as translated by de la Madelaine, begins

with something with which I disagree—the title. Burns entitled his poem

“Thou Lingering Star,” a completely appropriate title because the imagery is

stellar. In fact, the poem is probably better known by the first half of the

first line: “Thou lingering star.” De la Madelaine, however, calls his

translation (I am translating a translation) “To Mary in Heaven.” When we

take a close look at Richard de la Madelaine’s translating of Burns into

French we are tempted to conclude that Flaubert neglected to add that a

translation might be neither faithful nor beautiful.

Given the above, I think

that what disturbs me most about de la Madelaine’s rendition of the original

is that he uses the formal “vous” rather than “tu” in a love song to a woman

with whom he intends to go to Jamaica, and who may be bearing his child.

That might have been done in upper class society in France in the

mid-nineteenth century, but it certainly would not have been how

eighteenth-century Scottish peasants made love to each other. I am left with

the feeling that I am listening to someone who is trying over-hard to

impress a loved one. In my opinion this is the least of the three Highland

Mary poems in this collection, so it probably doesn’t much matter.

Apart from the three or four

lines of explanatory material which heads each poem, de la Madelaine does

not tell us why he chose the three Highland Mary poems to lead off his

selection. But why did Richard de la Madelaine choose three poems

about Highland Mary, rather than poems for any other woman, and give them

pride of place? I think that it is that Mary Campbell had a special place in

the heart of Robert Burns, as he had in the heart of de la Madelaine, and as

she has in the hearts of readers in our day.

Burns wrote so many great

pieces that very few people would come up with the same best ten or twenty.

And so I shall not request a show of hands, but I shall tell you two of

mine.

The first was written after

he had parted for the last time from his beloved Clarinda. Knowing that they

were never to meet again, he sent her a lovely song of parting with these

superb lines:

Had we never lov’d sae

kindly,

Had we never lov’d so blindly,

Never met—or never parted—

We had ‘ne’er been broken hearted.

That was, of course, a song

of parting, not one of death.

The forgiving and

long-suffering Jean is reputed to have said that her husband should have had

two wives. Wouldn’t it have been nice if that second wife could have been

Highland Mary Campbell?

AUGUSTE ANGELLIER

Obviously the time was ripe

for a serious and expansive study of Robert Burns, the man and the poet, in

French. The man who was to supply this was Auguste Angellier, who in 1893

published a State doctorate on the poet in two large volumes. For those of

you unfamiliar with the French educational system, the State doctorate was a

minimum registration period of five years; ten years is not at all uncommon.

Successfully passing the exam used to guarantee the candidate a university

position. The other doctorate available is the university doctorate,

equivalent to the British or American PhD. This is the degree which I hold

from the Sorbonne in Paris. If I may digress for a moment: when I was

setting up my university doctorate I asked if I could write a study of

French translations of Burns, which would, of course, have included

Angellier, but with no duplication of his work. I received a polite but

definitive answer: Certainly not, there has already been one thesis on

Burns. Naturally I did something else.

The classic arrangement of

such a work is that it be divided into two volumes, the first devoted to the

life of the subject, the second devoted to his/her work. At an earlier time

the candidate was required to produce a much shorter volume on a completely

different subject, to be written in Latin. No doubt when this requirement

was silently dropped, those of the older school wagged their heads and spoke

of the degeneration of French education.

It must be recalled that

when Angellier was doing his research for his monumental work (1031 printed

pages in all), research was what we today would call primitive. The National

Library of Scotland was still the Advocates Library with their much more

limited collecting desires. There was no registry of manuscripts, individual

libraries might have only hand-written lists, not really catalogues, of

their holdings. Thus the serious researcher had physically to visit each

repository of material he wished to consult. Even these had to be discovered

on one’s own. Once at the repository, there was no method of

photo-reproducing material other than hand copying it. I belong to the last

generation of poor souls who hand wrote all the information onto paper, and

was allowed to use only a pencil to do so. Imagine creating pages of

large-format type that way.

Considering these

restraints, and the fact that his work was published almost 120 years ago,

Angellier’s life of Burns is today still an important and readable work.

Angellier’s work is divided

into two volumes: The Life and The Works. In the first the author spends

considerable space on Mary Campbell, as he consistently calls Highland Mary.

For no obvious reason Angellier always calls Jean Armour Joan, as though it

were a diminutive form of the name. And Scots are very fond of diminutives.

According to Angellier Burns was deeply in love with Mary and was devastated

when he learned of her death. He mentions the poet’s intention to emigrate

with Mary and he translates the entire poem “Will Ye go to the Indies, My

Mary”?

JEAN-CLAUDE CRAPOULET

The most recent book of

translations of Burns is the work of Jean-Claude Crapoulet, published in

1994. The translator does not begin well in his fifty-two page introduction,

where, for a starter, he has Burns being born on January

twenty-third. In his resume of Scottish poetry he repeatedly refers to a

work which greatly influenced Burns—Allan Ramsay’s TEA-TABLE MISCELLANY,

which according to Crapoulet was the TEA-TIME MISCELLANY. I read the 53-page

Introduction before going on to the translations, and I was not encouraged

when I saw Robert Fergusson’s AULD REEKIE translated as OLD STINKY (12-1-8).

John Cairney would have loved that one.

Crapoulet mentions Highland

Mary specifically only very briefly, in the Introduction, suggesting that

she was a sort of plaything, soon forgotten. How then would he explain

Burns’s hauntingly beautiful “Thou Lingering Star” written years after

Highland Mary’s death? There are too many careless mistakes suggesting poor

research or poor editing. For instance Crapoulet refers to the noted Burns

scholar Hans Hecht (36) as Doctor Hans.

In essence while Highland

Mary is ill done in the introductory material, so are all the other figures

that people the Burns universe. So we should now examine the poems

themselves.

In assessing an anthology

one supposes that the critic should concentrate on what the editor included

rather than what was excluded. In his substantial collection of Burns’s

poems and songs Crapoulet included only one work about Highland Mary—“Afton

Water” as it is called. The translation is apt, if not very poetic. And

there is no attempt at rhyme. No one would quarrel with the inclusion of

this song, one of the finest and best known that the poet wrote. And perhaps

with the scant attention paid to Mary Campbell, one poem is enough.

But in the selecting process what happened to other gems such as “Ae fond

Kiss” or “Of a’ the Airts the Wind can Blaw”, written for Clarinda and Jean

Armour?

OTHERS

In 1988 there was published

a small volume of poems by Burns translated into Chinese. There were eleven

poems, one of which was “Highland Mary.” This is not the poem most people

would have chosen, which sang the praises of the woman Burns loved.

To illustrate the continuing

popularity of Highland Mary in 2012, a Ukrainian translated a selection of

Burns’s poems. There is a short bilingual Introduction, but there are no

notes to individual poems. Among the poems and songs we find “Flow Gently

Sweet Afton.”

There was no Portuguese

edition of Burns until I suggested to a Brazilian PhD candidate of mine,

Luiza Loba, that she translate a selection. I chose fifty poems. The work

was published in Rio in 1994.

In an ingenious sales plan,

the publishers boxed the volume with a miniature whiskey, so if the owner

did not warm to the selection or the translation, he or she could at least

enjoy Scotland’s greatest export.

We have had a brief look at

how translators have treated the subject of Highland Mary in two languages,

French and German,* with brief mention of other languages.

There are those who are

dismissive of this love affair, but any poet who could write “Flow Gently

Sweet Afton” and “Thou Lingering Star” had very certainly not taken the

event lightly. And Burns would certainly not have proposed emigration to

Jamaica with a woman who was just a passing fancy.

Robert Burns loved Mary

Campbell very dearly, and we have all been enriched by the tributes he paid

to his Highland Mary.

I wish to thank Elizabeth

Sudduth, Head of Rare Books at the University of South Carolina, Ms. Sej

Harman, and my wife Lucie for their assistance in preparing this article.

I also wish to thank my

friend Colin Hunter McQueen for lending me his eyes to read this paper.

|