|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Ken Simpson continues to hit

the “nail on the head” as a Robert Burns scholar and writer! As to Burns,

Simpson excels in both areas as his article proves and it is one of a

trilogy of conference articles on Highland Mary presented by Ken, Gerry

Carruthers and Ross Roy. The three were guests of the Greenock Burns Club

which is also known as “The Mother Club” in the global Burns community. The

conference was held on 21st April 2012 at Greenock Lyle Kirk and was

organized by President Margaret Dickson. She brought the three Burns

scholars together to commemorate Highland Mary, a.k.a. Mary Campbell. These

three added new insights to this almost mystical creature of love – Highland

Mary.

You can find Gerry’s article

in Chapter 128 of Robert Burns Lives! and Ross’s will appear later, perhaps

as early as next week. Chances are good that I will write a fourth article

on the conference itself to accompany this series of speeches. I have seen

some very good pictures of the participants in Greenock and, if they wind

their way to my office as promised, I think you will be pleased with them.

In the meantime, here is Ken’s article. (FRS: 7.18.12)

‘Love and Poesy’: Burns and Highland Mary

By Ken Simpson

Burns

loved a lot; Burns read a lot; Burns wrote a lot. This paper is about the

relations between these various activites. Burns

loved a lot; Burns read a lot; Burns wrote a lot. This paper is about the

relations between these various activites.

The first

point is widely acknowledged, not least by the poet himself. ‘There’s ae wee

faut they whiles lay to me;' I like the lasses – Gude forgie me’, he admits

in the first ‘Epistle to John Lapraik’. He makes the same point more

formally to Dr John Moore: ‘My heart was compleatly tinder, and was

eternally lighted up by some Goddess or other’ (The Letters of Robert Burns,

ed. J. DeLancey Ferguson; 2nd edition, ed. G. Ross Roy, 2 vols. (Oxford,

1985) I, 139). In his fifteenth autumn his partner at harvest ‘initiated

[him] in a certain delicious passion’ (137); and ‘among her other

love-inspiring qualifications, she sung sweetly’, the song reputedly

composed by a laird’s son. ‘I saw no reason why I might not rhyme as well as

he’ (138), writes Burns. The outcome was ‘O Once I Lov’d a Bonny Lass’,

inspired by Nellie Kilpatrick. ‘Thus with me began Love and Poesy’ (138),

Burns notes; and this was to be his first experience of committing ‘the sin

of RHYME’ (137). Likewise, in an entry for August 1783 in the first

Commonplace Book, he writes, ‘There is certainly some connection between

Love, and Music and Poetry’, and he acknowledges that he would never have

attempted poetry without first experiencing love. ‘Rhyme and Song [are] the

spontaneous language of my heart’ he says.

Love and

Poetry are regularly linked. When Jean gives birth to twins he sends

Richmond a copy of ‘Green Grow the Rashes, O’. Habitually he links

procreation and creativity; poetic licence meets sexual licence. Sending a

song, he writes ‘The inclosed is one which, like some other misbegotten

brats, “too tedious to mention”, claims a parental pang from my Bardship’

(Letters, I, 163-4). Even more revealing is this: ‘Making a poem is like

begetting a son: you cannot know whether you have a wise man or a fool,

untill you produce him to the world & try him. For that reason I send you

the offspring of my brain, abortions & all’ (Letters, II, 305).

While

recognising this linking of creation and procreation, it is important to

stress that Burns did not make love to every lady who inspired poetic

tribute from him; otherwise there would be many more descendants of the

Bard. Some relationships were consummated in verse and the flesh; others

only in print or song. For instance, the beautiful ‘O wert thou in the cauld

blast’, written for Jessie Lewars, might be said to be a song of love in the

purest sense. It is also worth noting Burns’s reactions when becoming a

father. His first-born, ‘dear-bought Bess’ prompts a poem while the mother,

Elizabeth Paton, gets no song from him (unless, as some have suggested, the

song, ‘My girl she’s airy’ refers to her; Burns later sent it to Ainslie

congratulating him on becoming a father). The Platonic relationship with

Agnes McLehose is commemorated in the song, ‘Ae Fond Kiss’, but Burns

satisfies his sexual needs with her maid, Jenny Clow.

As for his

reading a lot, in the same letter to Moore (Letter 125), Burns refers to his

‘reputation for bookish knowledge’ (Letters, I, 139) and his retentive

memory. Burns was highly impressionable and had formidable powers of

absorption and recall. Those early letters to Alison Begbie[?] reflect the

influence of his reading on expression of matters of the heart; likewise the

letters to old school-mates, Niven and Orr, represent how he thinks a

student of life should write (and aged 23 he wrote to Murdoch, ‘the joy of

my heart is to “Study men, their manners, and their ways”’, quoting

Alexander Pope (Letters, I, 17)). David Daiches suggested these were

exercise letters; Burns was trying his hand at various styles of writing.

Equally,

there were examples of amorous verse in the work of the vernacular Scots

poets. In Allan Ramsay’s ‘The Gentle Shepherd’, Patie (the Gentle Shepherd)

and Roger (‘a rich young shepherd’) discuss their young ladies, Peggy and

Jenny. In the poems of Robert Fergusson Burns encountered the pastoral

dialogues of Damon and Alexis. The key term here is ‘pastoral’: Burns is

absorbing the pastoral tradition in poetry. Whereas the urban Fergusson

masquerades as herdsman poet, Burns, as son of a tenant-farmer, is ideally

qualified to play the pastoral swain. In pastoral convention swains discuss

the merits of their respective mistresses. This finds an equivalent in

Burns’s boasting of his sexual prowess in letters to Richmond, Smith,

Ainslie and others (most obviously in the notorious ‘mahogany bed’ letter);

it is reflected also in the activities of the Court of Equity and the poem,

‘Libel Summons’, which Catherine Carswell published in 1930. The pastoral

swain of poetic convention experiences the realities of the flesh; this is

what you do if you’re a testosterone-charged young male with an eye for the

lasses and ambitions as poet. A key poem in this context is the epistle ‘To

James Smith’, written late 1785 or early 1786. It is revealing in three

respects: plainly Burns and Smith have discussed emigration (i.e. before the

Highland Mary relationship); here for the first time Burns indicates his

wish to publish (‘To try my fate in guid black prent’); and, distinguishing

himself from ‘ye douse folk that live by rule’, he identifies with ‘The

hairum-scairum, ram-stam boys,/ The rattling squad’.

But his

reading offers a template for another Burns. To Murdoch, he wrote, ‘My

favourite authors are of the sentimental kind, such as Shenstone...Thomson,

Man of Feeling, a book I prize next to the Bible, Man of the World, Sterne,

especially his Sentimental journey, McPherson’s Ossian &c., these are the

glorious models after which I endeavour to form my conduct’ (Letters, I,17).

This would apply to the conduct of his poetic persona as man of feeling in

poems such as ‘To a Mouse’ and ‘To a Mountain Daisy’ and perhaps to some

extent to his behaviour (e.g. in Edinburgh). The composition of ‘The Bonnie

Lass of Ballochmyle’ offers an instance of the man of feeling smitten. ‘A

maiden fair I chanced to spy/ her look was like the Morning’s eye’, he

writes. Though Nature provides an appropriately bountiful backcloth, ‘all

her other works are foil’d/ By the bony Lass o’ Ballochmyle’. He wishes that

she were ‘a country maid’ and he ‘the happy country swain’, removing the

class distinction between them. She is Wilhelmina Alexander, born 1753

(Mackay and others) 1756 (Hunter McQueen and Hunter), sister of the new

laird, Claud Alexander. According to James Mackay, ‘she was already in her

thirties and not, by any stretch of the imagination, “a bonnie lass”’,

though he cites no source for these aspersions on her looks. Mackay adds,

‘she thought that the writer was trying to take a rise out of her’ (Burns: A

Biography of Robert Burns (Edinburgh, 1992), p.246). No wonder, since she

had probably read Fielding’s Tom Jones (1748) where Fielding mocks the

behavioural excesses of popular romance through the conduct of his hero; and

the language of Burns’s letter to her bears a striking resemblance to such

passages in Fielding (there are echoes too in letters to Clarinda). While

Burns may well have been attracted to Miss Alexander, it is undeniable that

the encounter enabled him to try his hand at two different styles of writing

(the love-sick swain of the poem; and the romantic excesses of the letter).

The beauty

of Miss Lesley Baillie of Mayfield was such that Burns, meeting her briefly

in Dumfriesshire, was minded to accompany her and her father some fifteen

miles on their journey south; and the result was two songs. Revealingly, he

writes to Deborah Duff Davies, who prompted ‘Bonie wee thing’, ‘I am a

great deal luckier than most poets. When I sing Miss Davies or Miss Lesley

Baillie, I have only to feign the passion – the charms are real’ (Letters,

II, 216). ‘I have only to feign the passion’: since he quotes from it in

letters, we know that Burns was familiar with Shakespeare’s As You Like It,

where in Act 3, scene 3 he would encounter this exchange:

Audrey: I

do not know what poetical is: Is it honest in deed and word? Is it a true

thing?

Touchstone: No, truly: for the truest poetry is the most feigning and lovers

are given to poetry; and what they swear in poetry, may be said, as lovers,

they do feign.

Feigning

is integral to poetry. Poetry may be inspired by real life but it is not

real life. Truth to life and truth to poetry need not be the same thing: a

poem may be ‘true’ in terms of itself, its own context, which may be

imagined rather than actual. ‘Fiction, you know, is the native region of

poetry’ (Letters, I, 181) Burns tells Mrs McLehose, and in another letter he

declares, ‘Fiction is the soul of many a Song that’s nobly great’ (Letters,

1, 326). Burns is often at his best when he invents a persona (e.g. the

songs from female perspectives; the dying sheep, Mailie; the aged patriot

of ‘A Parcel of Rogues’; Holy Willie; Beelzebub; the Twa Dogs; and the

drinking-crony narrator of ‘Tam o’ Shanter’). He is a master in the creation

of a wide range of voices.

Now, in

stressing the importance of the role of the imagination, in recognising the

inescapable artifice of poetry, I’m not questioning either the existence of

Highland Mary or the significance, both personal and poetic, of Burns’s

relationship with her. Highland Mary may well have been subject to

mythification, as some critics have been arguing, but the springboard to

such myth-building is a body of undeniable fact. It is because we do not

know everything about someone (how can we?) that myths develop around them .

However, my concern here is with the songs which the relationship produced.

‘My

Highland Lassie, O’ was first printed in Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum,

vol. 2, February 14, 1788. The speaker rejects ‘gentle dames, tho ne’er sae

fair’ with ‘Gie me my Highland Lassie, O’. The sentiments are comparable to

those of the brilliant second stanza of ‘Mary Morison’, culminating in the

line that Hugh MacDiarmid so admired: ‘Ye are na Mary Morison’. David

Daiches notes an ‘interesting blend of simple folk elements and neoclassic

elegance’ (Robert Burns (Edinburgh, 1981), p.298). The chorus represents the

former, and stanzas 2 and 3 the neoclassical. Emphasising the lass’s ‘honor’,

the speaker vows he will ‘dare the billows’ roar...[and] trace a distant

shore/ That Indian wealth may lustre throw/ Around my Highland lassie, O’.

If the song is to be read autobiographically, this suggests Burns was going

abroad to make a fortune and return to her (i.e. Highland Mary remains in

Scotland). In concluding with a protestation of his love for her, he assures

the reader, ‘She has my heart, she has my hand/ My secret troth and honor’s

band’, implying that rings have been exchanged. Interestingly, the same

volume of the Scots Musical Museum includes the song, ‘Though Cruel Fate

should bid us part’, with comparable sentiments culminating in ‘Though

mountains rise, and desarts howl,/ And oceans roar between;/ Yet dearer than

my deathless soul/ I still would love my Jean’ (i.e. Jean Armour). This

song anticipates the beautiful ‘Of a’ the Airts’ which appeared in vol. 3 of

the Scots Musical Museum, 2 February 1790.

‘Thou

Lingering Star’ also appeared in that volume, with the title, ‘My Mary, Dear

Departed Shade’; it is also known as ‘To Mary in Heaven’. The first stanza

might suggest that the occasion is the anniversary of her death, but in

stanza 2 it becomes clear that it is their ‘one day of Parting Love’ that is

commemorated, and he preserves the image of her in their last embrace.

Recollection strengthens the image: ‘Time but th’impression stronger makes/

As streams their channels deeper wear’, in itself a fine image. The sanctity

of their love is emphasised: the hour of their meeting that day is ‘sacred’,

the location is the ‘hallow’d grove’ by the winding Ayr, while the river

‘gurgling kiss’d his pebbled shore’, which is what they cannot do –

embrace. Burns uses the Nature imagery to good effect, and I suspect that

the song has suffered because it is written exclusively in English. For me

the only problem is the histrionically egocentric conclusion, repeating the

last lines of stanza 1: ‘Seest thou thy Lover lowly laid!/ Hearest thou the

groans that rend his breast!’. Perhaps Burns was too close to his material

– essentially his feelings. He asked for Mrs Dunlop’s opinion since he was,

as he said, ‘too much interested in the subject of it, to be a Critic in the

composition’ (Letters, I, 451); but soon he was judging it ‘in my opinion by

much the best’ (Letters, I, 455). The intense focus on his feelings lends

strength to Daiches’ comment that this ‘makes it clear that Burns had some

reason to be remorseful’ (Daiches, 302); so too does the fact that he sent

it a second time to Mrs Dunlop along with a confused and highly charged

letter in which he broods on the afterlife that may await him. Plainly the

Highland Mary episode was preying on his mind.

‘Highland

Mary’ was published in George Thomson’s A Select Collection of Original

Scotish Airs in 1799. Burns’s use of imagery from Nature is particularly

effective in this song. His meeting-place with Mary is favoured by Summer as

the place where it stays longest; by implication, he too would linger

longest there – as Nature blossoms there so too did their love. Nature

imagery also informs the striking contrast which death brings: ‘Fell death’s

untimely frost/...nipt my flower sae early’. The contrasting of love’s

growth and death-brought decay is a stock feature of love poetry from

classical times onwards; one thinks of the carpe diem theme of Horace,

Shakespeare’s sonnets, and Andrew Marvell’s warning to his coy mistress. But

in the carpe diem tradition the contrast is used by the speaker as a means

of persuasion: seize the moment and make love for we are but mortal. Here

Burns’s unsparing realism adds poignancy: ‘Now green’s the sod, and cauld’s

the clay,/ That wraps my Highland Mary!’; and ‘mouldering now in silent

dust,/ That heart that lo’ed me dearly’. Mary, now dead, is beyond

persuasion; the reader (and, one suspects, Burns himself) are the objects of

persuasion: ‘But still within my bosom’s core/ Shall live my Highland Mary’.

He vows that she lives on in his enduring love for her. Why then would

Burns, in a letter of 14 November 1792, write, ‘The Subject of the Song is

one of the most interesting passages of my youthful days’ (Letters, II,

160)? ‘An interesting passage’: can the experience really be reduced to

these terms, or is he trying to play down a deep and abiding sense of loss?

‘Will Ye

go to the Indies, my Mary’, sent to Thomson, 27 October 1792 and first

printed in Currie, 1800, was partly inspired by the old song, ‘Will ye go to

the Ewe Buchts, Marion’? The question in the first line is rhetorical, and

by stanza 2 the Indies are present only as the source of exotic fruits whose

charms are surpassed by Mary’s. From addressing her, the speaker then turns

to address the reader/listener, stressing his Heaven-sworn vow of fidelity

to Mary. ‘And sae may the Heavens forget me,/ When I forget my vow!’: the

repetition of ‘forget’, along with ‘when’ rather than ‘if I forget my vow’,

may be of some psychological significance. She is then asked to plight her

troth with her ‘lily-white hand’ before he‘leave[s] Scotia’s strand’. The

rhetorical nature of the question is now fully confirmed. If the song is to

be read autobiographically, then Burns sails alone; Mary remains. By the

final stanza it is to be assumed that she has joined him in the plighting of

troths to share ‘mutual affection’. If this term is notably restrained, it

is offset by the vehement cursing of the cause of their parting. As with the

song, ‘Highland Mary’ here too there is a rather puzzling comment later from

Burns. On 27 October 1792 he wrote to Thomson, enclosing the song: ‘In my

very early years, when I was thinking of going to the West Indies, I took

the following farewell of a dear girl. – It is quite trifling, & has nothing

of the merit of “Ewebuchts”, but it will fill up this page’ (Letters, II,

154). All his earlier love-songs ‘were the breathings of ardent Passion’,

he adds, noting that to have given them ‘polish...would have defaced the

legend of my heart which was so faithfully inscribed on them. Their uncouth

simplicity was, as they say of wines, their RACE’. The attempt to be blasé

may conceal deeply troubling feelings.

Burns had

several times contemplated going abroad. A pattern can be detected. With the

approach of the birth of ‘dear-bought Bess’, he writes in ‘Epistle to John

Ranken’ using the metaphors of poacher with his gun and gamekeepers, the

poacher-court of the kirk session. He will be revenged for his guinea fine :

as ram-stam boy he vows that ‘the game shall pay, owre moor an’ dail,/ For

this niest year’. He will continue to have sport (i.e. sexual encounters)

even though ‘I should herd the buckskin kye/ For’t in Virginia’. Yet again,

in the summer of 1787, faced with Peggy Cameron’s writ in meditatione fugae

(literally ‘on the contemplation of flight’), flight is precisely what he

considers. To Smith he writes, ‘I cannot settle to my mind...If I do not

fix, I will go for Jamaica’ (Letters, I, 121).

Finally to

a song which not everyone would agree should be included here. ‘Afton

Water’, published in Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum, vol. 4, 13 August 1792,

must have been written before 5 February 1789 when Burns sent it to Mrs

Dunlop, the first line reading, ‘Flow gently, clear Afton, among thy green

braes’. The language and rhythms here are especially effective. The stream

murmurs out of consideration for the sleeping Mary and the birds are charged

not to disturb her slumber. In an idyllic landscape the speaker is once

again the poet-swain of pastoral, herdsman to his flock. Commentators

(Kinsley, for instance) are reluctant to concede that Highland Mary is the

subject, and there may be substance to this: Mary is a stock name in love

song; Highland Mary had died well before the move to Dumfriesshire; and

Burns wrote of the song in that letter to Mrs Dunlop,’ I have a particular

pleasure in those little pieces of poetry such as our Scots songs...where

the names and landskip-features of rivers, lakes, or woodlands, that one

knows, are introduced. I attempted a compliment of that kind to Afton’

(Letters, I, 370).

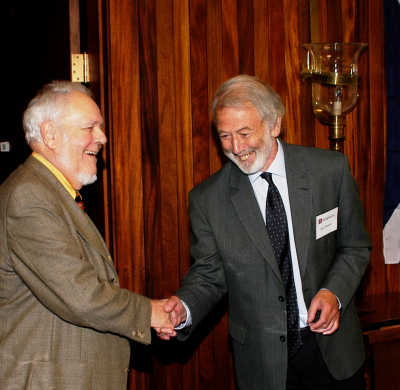

Professors Ross Roy and Ken Simpson celebrating

the 80th birthday of Ross

at the University of South Carolina Burns Conference in 2004

Why

contradict the testimony of the poet (it’s not about Highland Mary; it’s

about the river Afton)? Partly because I think it’s the best of the lot. But

there is something else. Burns, you will remember, had written, ‘Rhyme and

song are the spontaneous language of my heart’. In 1800 in the Preface to

the Lyrical Ballads Wordsworth defined poetry in remarkably similar terms:

poetry is ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’, but with this

important qualification: ‘it takes its origin from emotion recollected in

tranquillity’. ‘Emotion recollected in tranquillity’: is this not what Burns

achieves in ‘Afton Water’? In the transposition of Mary Campbell to the

benign tranquillity of the banks of the Afton she is revivified to enjoy

true rest, and Burns achieves a reconciliation of the complex and often

conflicting emotions which her memory had previously aroused. |