|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

We come

today to pay tribute to the man responsible, more than anyone else, for us

celebrating our annual Burns Suppers all over the world. He has been a hero

of mine for many years, and I usually get around to mentioning him a wee bit

when I speak at Burns Suppers or meetings. I do not believe he could foresee

that he was starting a movement that would grow internationally and involve

millions of people over the years. This remarkable man was the Rev. Hamilton

Paul.

I know

of no one more fitting to talk about Hamilton Paul that our friend Clark

McGinn who has traveled more miles to speak on Burns than anyone else in

history. You may think that is an inaccurate statement, but try and name

another individual who, in

the last seven years, has traveled 166,000 miles (6.7 times

round the globe) to deliver 100 speeches on Burns in 26 cities in 13

countries, and all of them carbon neutral!

I have tried several times through my research to find a

picture of Hamilton Paul, beginning with Clark and followed by Gerry

Carruthers at the University of Glasgow, Patrick Scott at the University of

South Carolina, and Alastair McIntyre, editor/owner of

www.electricscotland.com – all to no avail. If any of our readers are

aware of a photo of Rev. Paul, please send it or any related information to

me and I will see that it is placed with this definitive article by Clark

and full pictorial credit will be given to the sender.

Thank you, Clark, for the time and energy spent on

researching and writing your article on Rev. Paul for the pages of

Robert

Burns Lives!

- I’m sure it will surface in other magazines or chronicles. You did him

proud, and we are proud of you sharing this article with our readers! (FRS:

5.30.12)

A FORGOTTEN HERO

By Clark

McGinn

In the

history of commemorating the life and works of Robert Burns, many names jump

out: we remember national leaders and statesmen who contributed great

speeches to his memory such as Abraham Lincoln or Lord Rosebery; or

churchmen who found solace in his words, including Henry Ward Beecher or

Martin Luther King; there were those who found Burns in the land, as did

Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir; we live with the ever growing army of

memorialists, biographers, sculptors, founders of Burns Clubs and the Burns

Federation, in particular Colin Rae-Brown; and after a long period of

academic neglect, a growing band of keen scholars.

There

is one name, which should be shouted from the thatched roof of Burns

Cottage, commemorated in countless Standard Habbie verses, and have his

likeness engraved on the back page of every Burns Supper programme, yet,

this engaging and interesting character is hardly known at all.

His

name? The Reverend Hamilton Paul.

His

gift to the world? The Burns Supper.

When

the nine million or more folk who slice open a haggis and toast the Immortal

Memory around Burns’s birthday on 25th January each year, a tiny

handful know that they are following a ritual created by this forgotten

Scottish clergyman. And I for one would like to make amends to my fellow

Ayrshire-man.

In 1773

while our Poet was travailing on the fields of Mount Oliphant and first

thinking of verse and Nelly Kirkpatrick, a boy was born in Bargany, Near

Cumnock (Carrick’s ancient capital) to Mrs John Paul the wife of manager of

the Duke of Hamilton’s coal mines. This firstborn was christened after his

father’s employer and in that guise, young Hamilton Paul made his first and

not last into the records of the Kirk. By coincidence, after the Pauls

moved, another famous minor poet – excuse the oxymoron - Hew Ainslie was

born in the same cottage nineteen years after. This man was to emigrate to

the USA and became one of the great promoters of Burns’s memory as a living

example to the spirit of democracy and manifest destiny. Ainslie died in

Louisville KY in 1878.

Hamilton was a bright lad and excelled at his books such that his father

sent him up to The University of Glasgow and where he made lifelong

friendship with a classmate called Thomas Campbell, one of the great

Nineteenth century poets (although very out of fashion today). The poet and

the poetaster treated, complimented, and debated with each other in rhyme –

but when it came to their greatest poetic tussle – the University’s gold

medal for poetic composition, it wasn’t the bookmakers favourite Campbell

who carried the prize, it was the professors’ favourite, the charming

Hamilton.

This

untoward result made no difference to the two men and their friendship, who

upon graduating took the then common role of tutoring in wealthy families,

which left good time for the friends to correspond. After this pedagogic

period, Paul went back to Glasgow to study Divinity, taking his Bachelor of

Divinity degree and returning south to his home county in 1800. He couldn’t

find a full time ministry – that needed patronage – so he took the post of

assistant minister in the parish of Coylton (a village to the East of Ayr,

traditionally supposed to have been the seat of ‘Old King Cole’ of nursery

rhyme fame) but the records do not seem to show this as a particularly

arduous role, even though the minister, Revd David Shaw was in his eighties,

and it was the accumulation of free time which allowed Hamilton to join in

the busy social life of a thriving market town like Ayr.

Looking

back at those halcyon days, his obituary recalled that the young reverend

not only juggled with teaching French and Latin to five families, and

covered the pulpit for a similar number of the Ayr Ministers, he:

was whirled

about in a perpetual vortex of business and pleasure, never a single day

without company at home or abroad. If he could obtain three or four hours

sleep, he was satisfied. He was a member of every club, chaplain to every

society, had a free ticket to every concert and ball, and was a welcome

guest at almost every table.

And on

all these occasions, his wit, good nature and facile poetry gained him many

friends (and a fair few free dinners!) Most of his poetry was literally

ephemeral – a thought or sentiment captured on a day, scribbled on a scrap

of paper or a napkin, recited to the cheers of the diners, concertgoers or

presbyters, then lost on the wind. Again, with hindsight his obituarist

remembered:

Volumes might

be filled with selections from Mr. Paul's poetical compositions. They are to

be found scattered over magazines, reviews, and newspapers, for upwards of

sixty years. He wrote on every kind of subject, and in every species of

measure. His compositions are characterised by great elegance, but they

exhibit versatility of talent and facility of versification rather than

capacity to reach the higher flights of poetry.

His felicity with words prompted his muse to exercise herself

on many subjects: the rolling Ayrshire countryside, the glory of the Psalms,

the joys of friendship. His enquiring mind though drew him to some rather

more unusual topics including the wisdom of teaching girls physics (‘First

and Second Epistles to the Female Students of Natural Philosophy in

Anderson's Institution’), in advocating new developments in healthcare

(‘Vaccination, or Beauty Preserved, a poem), or a hymn to the art of making

Ayrshire’s famous Dunlop Cheese. The combination of love of both food and

county makes this a typical Paul poem:

On Tuesday

morning at the peep of light,

Take all the milk that has stood overnight,

and, by the lustre of the dawning beam,

With a clean clam shell, skim off all the cream,

And from her lazy bed the dairy maid

Be sure to rise, and call her to your aid;

With rosy cheeks and hands as soft as silk,

Bid her hang on the pot and warm the milk,

Let not her heat it with too great a lowe,

But make it tepid, as warm from the cow;

Restore the cream, and put in good strong steep,

But through the molsy first let the milk dreep.

Now pay a due attention to my words;

And press, O gently press, the snow white curds;

Nor mash them small, (now mark well what I say)

Till you have squeez'd out almost all the whey.

Light be the weight for hours, one, two, or three,

And then the pressure may augmented be,

Oft change the clouts, and when the cheese is dried,

Send for the Parish Minister to try't.

His love of writing pressed him to submit his longer works to

the press, and in 1810, Peter Wilson (the brother of Wilson the printer of

the Kilmarnock Edition) was a sick man seeking retirement and he offered the

editorship and majority shareholding of The Ayr Advertiser to Paul, who

snapped up the opportunity. For three years he relished the role – the

recorder of the comings and goings of his town and the attendant country

parishes, adding historical and regional essays to the news and views,

amidst the ‘hatches, matches and dispatches’ that are still the core of that

paper’s appeal to the people of Ayr today.

In 1813 his hard work paid off, as a local landowner Richard

Oswald (whose grandfather was the largest slave dealer in Scottish history

and whose granny was the Mrs Oswald whom Burns horribly lampooned when he

was thrown out of an inn to make way for the poor lady’s funeral party) had

interests in the Borders and presented Hamilton to the charge of Minister of

the trifold parishes of Broughton, Glenholm and Kilbucho, in Peebles-shire.

Now facing the responsibilities of a real parish and the duties attendant on

his own pulpit, Paul had to pack up his comfortable life in Ayr, selling his

shares in the advertiser for a whopping £2,500 and in a final happy jeu

d’esprit, preaching his farewell sermon to the ‘honest men and bonnie

lasses’ of Ayr on the text :Acts

of the Apostles chapter XX, verse 37.

(In

case you have forgotten the quotation it is: ‘And they all wept sore, and

fell on Paul’s neck’ – he did have the sense not to finish the verse which

concludes ‘and kissed him’).

He

packed his clerical bags and decamped to the beautiful Borders, setting up

his convivial home round a cheery heath and a welcoming table in Broughton

Manse, where he ministered to the spiritual, poetical and culinary needs of

his happy flock until he died on 28th February, 1854, a

well-loved bachelor minister (he poetically proposed to the landlady of the

ancient Crook Inn – the poet Hogg’s local pub and a bar which had Burns,

Scott and century later John Buchan as regulars, but his versicles were

insufficient to turn Jenny’s head). Looking at his life, he appears almost a

walk-on character in a novel by Sir Walter Scott and in death, true to form,

he sleeps under a crazy monument ornamented extravagantly with a cherub, a

lyre and sheaves of poetic his ephemeral compositions.

A

thousand words into this essay, and I hear the reader say – might have been

nice to meet him, bet you the poetry got a bit dull after a while , but he’d

make sure your glass was full. But why is he anything important – there are

hundreds of dead and eccentric ministers – why choose this one?

Fair

point, dear reader, the great centre of Paul’s life and the reason he is one

of my heroes (and I hope will be one of yours after reading this) is that as

a poet, and a ‘New Licht’ (reform-minded) minister, Hamilton Paul was an

avid reader of Robert Burns’s works. So in 1801 when ex-Provost John

Ballantine, Burns’s old patron, decided to mark the fifth anniversary of the

poet’s early death with a Memorial Dinner, he asked two friends to persuade

Hamilton Paul to make the arrangements. And this it was that on 21st

July, 1801 in the ‘But’ of the Burns Cottage in Alloway, Reverend Hamilton

Paul invited eight men to convene and eat dinner in memory of their poetic

friend, in a way that seems so modern, so recognisable to us:

These nine sat

down to a comfortable dinner, of which sheep's head and haggis formed an

interesting part. The 'Address to the Haggis’ was read, and every toast was

drank by three times three, i.e., by nine

Hamilton Paul had invented the Burns Supper. He used concepts familiar to

him as a Scottish Freemason, and took themes from the poet’s own like to

create this memorable commemoration. The guests were very happy: Ballantine

and ‘Orator Bob’ Aitken (to whom RB had dedicated the Brigs of Ayr and The

Cottar’s Saturday Night respectively); Patrick Douglas of Garallan (who

found him that damnable job in Jamaica); David Scott (the banker who had

been arbiter for RB’s father’s dispute with his landlord); William Crawford

(whose father employed the poet’s father); Captain Primrose Kennedy (who had

been ambushed with Braddock, and invalided out after Bunker Hill); Thomas

Jackson (the Rector of Ayr Academy) and Captain Hugh Fergusson, the

barrackmaster of Ayr.

Before breaking up, the

company unanimously resolved that the Anniversary of Burns should be

regularly celebrated, and that H. Paul should exhibit an annual poetical

production in praise of the Bard of Coila, and that the meeting should take

place on 29th January, the supposed birthday of the Poet

And in the interval,

Hamilton Paul wrote reports for the papers starting an annual event which

took hold, as we well know, not just in Alloway, but through the West of

Scotland and out to the whole world, each dinner following Paul’s blueprint

of haggis, toasts and poems. For the toast to Burns – what we now call ‘the

Immortal Memory’ – Paul started a tradition of writing a poetic tribute (and

he was known as the ‘poet laureate’ of the Allowa’ Club) and to modern ears,

this is a tradition that will not be missed. While we applaud the

sentiments, the style seems at least quaint, and maybe simply awful.

He

wrote the first nine Odes and attended each Supper (though he would give the

honour of recitation often to the chief guest) until his decampment to

Peebles, but in the following years, he helped his Ayr friends by mailing an

annual verse for them. This is an untypical example, it is shorter than

most:

He also

established the first Burns Supper in Glasgow, for The Glasgow Ayrshire

Society in 1812, and ghost-wrote its Annual Ode to The Immortal Memory for a

long time (all of these are lost), and finally was the lynchpin of the

Broughton Burns Club, his enthusiasm being so keen that the local publican

changed the village pub’s name to The Burns Inn. While living in Broughton,

it was Paul who rescued the Brig o’Doon, made famous by Tam o’Shanter, from

destruction by the philistine Roads Commissioners who saw not the beauty and

poetry in the bridge, but sought the ‘keystane o’ the brig’ as good stones

to repair a few furlongs of road at a lesser expense. Paul’s poem ‘An Appeal

from the Old Brig o’Doon’ captured the attention of everyone whose

imagination had been captured by the closing scenes of Tam’o Shanter and the

public subscription shamed the petty officials into saving this piece of

national heritage.

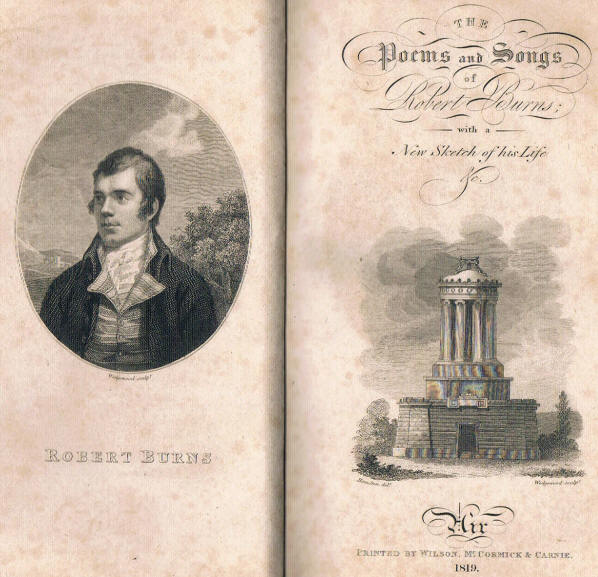

The

Burns Monument, too, owes a debt to our cheery chaplain. He read a notice in

the papers that there was to be a public meeting in the town hall of Ayr to

raise the subscription to a fitting Monument to Ayrshire’s bard. He arrived

post-haste to find but one other in the room: Alexander Boswell of

Auchinleck (Bozzie’s son and a leading Tory landowner). Slightly perplexed

at the absence of popular support Paul called Boswell to take the Chair

anyway, and from that position of authority Boswell appointed Paul Secretary

of the meeting, with the upshot that the motion to proceed with the

subscription was carried (as Paul reported to the papers) ‘nemine

contradicente’, but then it’s pretty easy to get unanimous majority of both

attendees!

All’s

well that ends well, and the two gentlemen were proud on Burns‘s Birthday

1820 when in full Masonic fig, in the company of hundreds of brethren,

Brother Boswell (Depute Grand Master) followed the benediction prayer of

Brother Paul (Lodge Chaplain) to lay the foundation stone. They worked

together until poor Boswell was slain in a duel, leaving the Auchinleck

properties embarrassed, and Hamilton Paul lonely.

The

culmination of Paul’s love of Burns was his editorship of the 1819 Ayr (or

Air) edition which was printed by his former colleagues at the Advertiser:

Wilson Jr and McCormick: not one to wear his colours on his sleeve Hamilton

resolutely entitled his edition:

The poems & songs, with a

life of the author, containing a variety of particulars, drawn from sources

inaccessible by former biographers. To which is subjoined, an appendix,

consisting of a panegyrical ode, and a demonstration of Burns' superiority

to every other poet as a writer of songs. By Hamilton Paul

He

upheld banner for Burns against naesayers like his fellow minister William

Peebles, who called the Greenock Burns Supper ‘Burnomania’ and was

insightful on Burns’s pastoral poems and the value of Burns’s work in

capturing Scottish song. Where he broke ranks was on the clerical satires.

This causes a firestorm. Holy Willie’s prayer alone was seen by many as

utterly unacceptable, our Hamilton looking for a softer view of human

frailty than the ‘Auld Licht’ über Calvinists, saw Burn’s sharp tongue as a

refiner’s fire to burn out the hypocrisy of the old school.

The

case drew much comment for and against, JG Lockhart, Scott’s pugnatious Tory

son-in–law

The Reverend

Hamilton Paul may he considered as expressing in the above, and in other

passages of a similar tendency, the sentiments with which even the most

audacious of Burns's anti Calvinistic satires were received among the

Ayrshire divines of the New Light. That performances so blasphemous should

have been, not only pardoned, but applauded by ministers of religion, is a

singular circumstance, which may go far to make the reader comprehend the

exaggerated state of party feeling in Burns's native county

While

in a later edition of the Complete Works, Hogg (The Ettrick Shepherd’) could

but cuddle him:

the Rev.

Hamilton Paul. There is a hero for you. Any man will stand up for a friend,

who, while he is manifestly in the right, is suffering injuries from the

envy or malice of others; but how few like Mr Paul to have the courage to

step forward and defend a friend whether he is right or wrong.

The Rev.

Hamilton Paul stood forward as the champion of the deceased bard, and in the

face of every obloquy which he knew would be poured on him from every

quarter as a divine of the Church of Scotland ... yet he would neither be

persuaded to flinch from the task, nor yet to succumb, or eat in a word

afterwards. ... I must acknowledge that I admire that venerable parson

although differing from him on many points.

The

wrath of the diehards almost caused the case to appear before the highest

disciplinary court in the General assembly of the Church of Scotland, but

the debate petered out before the wrathful divines could meet in Edinburgh.

But it would take a lot more than these tempests to blow the equanimity of

the jolly clerical gent off course.

He

carried on hosting happy dinner parties and undertaking the duties of his

cloth – in those days and until comparatively recently in the kirk the mark

of a Minister was the quality of his sermons, which his obituary called '

not of the kind calculated to attract the million’ but it was neither his

prose, nor even truly his verse which makes him a forgotten hero. It was

taking elements of Burns life and writings and creating a ritual to remember

him by. He even foretold the global spread of the Burns supper:

In his

Edition of the Bard’s works, Hamilton said that the world had given our poet

‘ever honour except canonisation’ and because of his efforts, and genius in

inventing the Burns Supper, 193 years after Paul wrote that summation, ,

Burns has even achieved a secular form of canonisation, with Burns Night

being the true national day of Scotland.

Thank

you Hamilton Paul!

© Clark McGinn, 2012.

|