|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

Gerry

Carruthers is no stranger to the pages of this web site nor to Burnsians

around the globe. I am always honored when he submits one of his articles

for our readers and this particular one will be a treat for all. Susan and I

have been to The Mitchell Library in Glasgow in days gone by, and I cannot

recall if our small town basketball court in Mullins, SC was any larger than

The Mitchell. Naturally we were impressed with the library, and I could very

easy designate it the “Mother Library of Robert Burns”.

I have

found Gerry’s scholarship to be of the highest quality. He is the author/editor of

many books on Burns, four which grace the shelves of my library. He

co-edited Reliquiae Trotcosienses, “a guide to Abbotsford and to its

collection”, with Alison Lumsden on Sir Walter Scott that I particularly

enjoy and value since Scott was a hero of mine long before Burns. His book,

Scottish Literature, is one every Burnsian should own since it deals topics

like The Rise of Scottish Literature, Scottish Literature in Scots, Scottish

Writing in English and Literary Relations: Scotland and Other Places.

Gerry’s research in all of the above is self-evident and places him among

the top Scottish writers around the globe.

It has

been a pleasure to work with Gerry on projects at the Burns Club of Atlanta

and at The Centre for Robert Burns Studies at University of Glasgow. I must

admit I was overwhelmed and honored over a year ago when I was invited to

become a member of the Centre’s Business Board.

With great

pleasure, once again, I present Dr. Gerard Carruthers!

This is a

version of a talk delivered by Gerry Carruthers at The Mitchell Library,

Glasgow, 23rd February 2012.

The

Mitchell Burns Collection:

The Best in the World?

By Gerry Carruthers

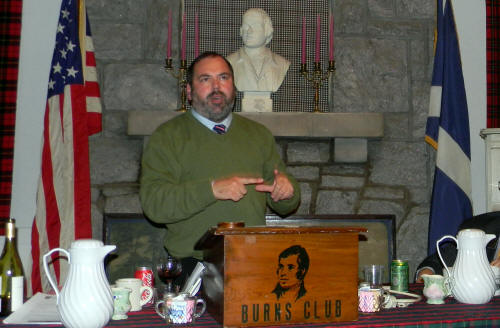

Dr. Gerry Carruthers speaking at the Burns Club

of Atlanta in November 2011. Photo by member Keith Dunn.

My title

asks whether the Mitchell Burns collection is the best in the world. Let me

begin by ducking the question - although I will come back to this - and say,

it is a unique collection. And by unique collection, I do most certainly

mean that as a term of praise. Sometimes things are unique because no-one

else wants them! There are things in this room that would make the dedicated

Burns collector or fan, salivate! And I’ll mention some of these treasures

presently.

An

indispensable guide remains to the Mitchell collection remains the ‘Robert

Burns Collection Catalogue’ first compiled for the bicentenary of the Bard’s

birth in 1959, and updated for the bicentenary of the death in 1996 by the

late great Joe Fisher, a man’s whose kindness and intelligence were very

much appreciated by several generations of Glaswegians seeking out the

wisdom contained in this great library.

The

Catalogue tells us that the core of the Mitchell Burns Collection is formed

by 700 volumes bought from James Gibson of Liverpool in 1882. Now this is

significant not only due to the obvious fact that the library is founded in

the late nineteenth century, albeit that the oldest part of the current

edifice dates to 1911, but because this purchase represents a wider

phenomenon: and that is that the period from the 1880s-1920s is the

highpoint of Burns ‘collection’. The Mitchell might simply have bought

collected works: poems, songs, letters, prose and some other material:

criticism, biography, even a little ‘memorabilia’ (or ‘Burnsiana’ as it was

described in the 1959 catalogue). And that would have been more than enough

for the public in general. The Mitchell went much further however, by buying

700 volumes, expanded to around 5,000 items in the Burns collection today

(so including some hundreds that are not included in the 1996 catalogue).

The idea

of having a Burns Collection begins in the Victorian period – this is when

values for Burns materials – books, manuscripts & memorabilia begin to

become serious. This is partly to do with the rise of consumerism in the

latter half of the nineteenth century and also a sufficient period to have

elapsed for Scotland to be more or less unequivocally proud of THE BARD.

Related to this, Burns becomes ever more seriously an object of serious

scholarly investigation.

Let’s

think about some of the highlight. Burns’s first book, Poems, Chiefly in the

Scottish Dialect published in 1786. There are, according to the calculations

of a gentleman doing a census from Florida, around 72 or 73 of these volumes

still in existence. That’s out of an original 612. The ‘Kilmarnock’ is the

crowning jewel of a Burns collection. The Mitchell has 2! Just to give us

some idea of monetary value, the ‘Kilmarnock’ edition over the past decade

has sold for anywhere between 30 & 80,000 pounds depending on provenance or

association and condition. The second of the Mitchell’s ‘Kilmarnock’s has a

missing original title and contents pages, but would still easily fetch

upwards of £30,000 were it to go on sale.

Burn’s 2nd

– ‘Edinburgh’ edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect published in

1787 is an item of which the Mitchell has 7 copies, out of an original 3,000

plus produced. Not so rare, you can buy one of these for a couple of

thousand pounds upwards. Not only this, but the ‘Edinburgh’ has two separate

‘issues’: notoriously one of these in ‘To A Haggis’ has ‘stinking ware’ in

the text instead of the correct ‘skinking ware’. The Mitchell has two

‘stinking’ copies. The ‘Edinburgh’, issues 1 & 2 both, is or are the next

cornerstone, after the ‘Kilmarnock’, of a Burns Collection. This library has

also three copies of the expanded 1793 ‘Edinburgh’ edition and two of the

new edition of 1794. So that’s pretty much the crucial books of poetry

published during Burns’s lifetime covered. The other item here for Burns

completists is the songs collected and written by Burns and published in

James Johnson’s The Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) – so stretching half a

dozen years beyond the poet’s death by the time the sequence is complete.

The Mitchell has one complete set of the original, two sets of volumes 1-5,

and the late eighteenth century reissue dedicated to the Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland. Also there are the Kilmarnock and Edinburgh volumes

and Scots Musical Museum. Many Burns collectors have spent their whole lives

trying (often unsuccessfully, sadly) to complete this set.

For me,

the fourth cornerstone for the serious collector of printed Burns work is

the first ‘Collected’ works and full-length ‘biography’ of Burns, James

Currie’s four volume The Poetical Works of Robert Burns (1800). The Mitchell

has 2 sets; and also numerous subsequent editions – and not only editions

but a huge array of the ‘Works’ published all across the globe which

cannibalize the ‘Currie’ edition.

So far,

there is no single collector who can match up to the Mitchell in terms of

printed ‘editions’, 1786-1800, or in a sense 1786-1830s, which remains the

period when the ‘Currie’ is dominant. At this point we can say, certainly,

the collection is the best in the world. I’ll be turning my attention to

producing a new edition of Burns’s Poems in the next few years for our

Oxford University Press edition, and the first port of call for me in terms

of printed books during Burns’s lifetime is The Mitchell – there is no

better place in the world to begin that research into general ‘stemma’ – the

poetry-texts and how these develop across different publications during

Burns’s life-time (and beyond).

One of the

advantages that the Mitchell has over the National Library of Scotland or

the British Library is that these copyright libraries automatically receive

everything published in the British Isles. The Mitchell does not, of course,

and so has to be proactive. In terms of Burns – first of all building on

James Gibson’s collection, which contained crucial overseas editions

including the first American edition – published in Philadelphia in 1788,

this has meant the library being proactive in seeking out (sometimes being

gifted) foreign edition of Burns. There are a couple of dozen US editions of

Burns’s work, or Burns ‘Americana’ if you like, bested only by the more

extensive American holdings of the Thomas cooper Library at the University

of South Carolina, and rivalled to some extent by the collection of the

central freemasonic lodge in Washington City, USA. The Mitchell also has

important holdings in European editions of Burns, some nineteenth but many

twentieth century, and also translations into 32 languages (according to the

catalogue, but 36 or 37 in actual fact). The 32 are: Belorussian, Bashkir,

Bohemian, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Dutch, ‘English’ (not sure about that

one!), Esperanto (it gets worse!), Faroese, French, Gaelic, Galician,

German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Latin,

Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portugese, Rumanian, Russian, Slovakian,

Spanish, Swedish, Swiss German and Welsh!

Let’s turn

to manuscripts. The Mitchell has nothing like the collections to be found at

the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh University Library, the Pierpont

Morgan in New York, the Rosenbach in Philadelphia, the Thomas Cooper Library

in South Carolina, the Birthplace Museum in Alloway or, what is for me the

most breath-taking collection of all: that at Dean Castle Country Park,

where the Burns Federation also has its headquarters. However, what it does

have is a number of superb items – manuscripts for ‘Auld Lang Syne’ – I

think the last major (6 figure!) purchase made by the library, a couple of

poems and a few songs. Poems include ‘When by a gen’rous public’s kind

acclaim’ and ‘The Ordination’, one of Burns’s most important Kirk satires.

I’ve spoken at length in this venue previously about the latter: ‘The

Ordination’ is a remarkable document in local church politics. The

manuscript shows Burns working on a kind of propaganda. It is a remarkable

text because it shows Burns against ‘the people’, unfairly castigating the

Kilmarnock weavers for wanting to choose their own minister. This is Burns

the defender of Patronage, or Lairds choosing ministers. It is one of two

manuscript versions recorded – I don’t know where the other one is. And

James Kinsley the last editor to properly edit the complete poems seems not

to have used The Mitchell version. The penny has only dropped for me

recently that this manuscript has not properly been worked upon – we’ll do

so in the new OUP edition.

The other

song manuscripts in Burns hand are ‘O poortith cauld, and restless love’,

‘Thou whom chance may hither lead’ and ‘Yestreen I had a pint o’ wine’.

That’s a nice new flat or sports car you could buy if you were to sell

these!

There are

nine autographed letters in Burns’s hand: one on loan from Glasgow Life and

two deposited by the Burns federation, for reasons I can’t claim to

understand. All of these are significantly important (each would probably

fetch somewhere in the region of £6-9,000 if auctioned): and one Burns’s

only extended epistolary performance in Scots, his letter to William Nicol

of 1787, would most likely go for at least £15,000 and perhaps as much as

£30,000 if the Mitchell was daft enough, which it isn’t, to sell! This is a

tour de force Scots prose performance by Burns. Have a look at it in an

edition of his letters if you haven’t seen it, and marvel at what a

brilliant writer Burns is! As a great lover of the Mitchell Library, as

someone hugely indebted to its collections and staff over the years, I

regard myself as a kind of ‘critical friend’, and I’d want to raise the

question why the Mitchell does not enter into the market more often for the

Burns manuscripts, especially letters that come on to the market. I assume

the answer to some extent is that funds are tight. I know too that culture

is one of the first things to be hit within local, civic institutions when

times are austere. But we must never tire saying that ‘culture’ –

literature, the arts, music, history etc. etc. – is not a luxury! It is

about our identity, especially our local identity – in the case of the Burns

collection, all of Glaswegian, west of Scotland (including Ayrshire!) and

Scottish identity more widely; it perhaps even pertains, one might suggest,

to our British cultural identity – Burns is, among other things, a great

British Romantic writer, recognised as such the world over. He is, then, too

a Global writer. Identity, our own sense of ourselves as a cultured people –

fellow weegies!, fellow west of Scotlanders, fellow Scotlanders, fellow

Britons, fellow human beings! Culture and the pride we take in it is also

about our well-being, both physically and mentally – ‘man does not live on

bread alone’ but also on our imaginative engagement with the community, with

the world around us. That is what libraries are about – knowledge, often

practical knowledge that is true, but imagined knowledge – poetry, the other

arts that are as actually a part of our world as much as books, knowledge

about car mechanics, flower arranging, or splitting the atom! Libraries are

about whom we are, individually and collectively; they are about the human

world. So all of that by way of an appeal to the Mitchell! Please buy, if

possible, more Burns manuscripts. One of the places where we see the

Mitchell not quite keeping track of the contemporary scene, and here again I

hope I’m being a ‘critical friend’ is in its absence of Antique Smith

manuscripts – Alexander Howland Smith – the man who was jailed for a year in

1893 for forging, among other writers and historical figures, the work of

Burns. Antique Smith is now very collectible.

The

library also has a fairly large collection of manuscripts in facsimile,

which is very useful. And also a couple of important ‘Non-Burns Holographs’:

Gilbert Burns’s Mossgiel farm rent-book and Mrs Robert Riddell’s

‘Fragments’ manuscript volume (essentially Elizabeth Riddell’s commonplace

book). Robert Riddell was Burns great friend during the Ellisland years in

Dumfriesshire, until Burns committed some, seemingly drunken social faux

pas, either against Elizabeth or one of the other female members of the

Riddell household (one of the lowest moments in Burns’s life, leaving aside

the death of loved ones). Not mentioned in the catalogue, is a very

important manuscript collection: the letters of James Currie, Burns first

editor that we’ve recently finished editing at the University of Glasgow (a

very good piece of co-operation between the Mitchell and GU).

You see

excellent though it is in so many ways, the printed Mitchell catalogue is

now a bit problematic. As Joe Fisher makes clear in the preface to the 1996

catalogue based on the original 1959 one: ‘the method used was copied from

the massive Memorial Catalogue of the Burns Exhibition, Glasgow 1898’ – And

this was as more about EXHIBITING Burns rather than curating or cataloguing

Burns. For the proper curation and cataloguing of the Mitchell Burns

collection what we now need is a full electronic database management form of

catalogue. So that for instance, this might still produce editions of Burns

under place – very useful as this stands in the printed catalogue, but what

is lost in this arrangement is chronology – a computer catalogue instead

could produce all Burns editions published in 1822 or, indeed, all items of

any kind – works, biography, criticism, published say in 1955. It is a very

useful in the printed catalogue for instance that under manuscripts we find

not only the manuscripts actually owned by the Mitchell but also important

articles, pamphlets etc. on manuscripts elsewhere, including forgeries. So

the catalogue is attempting to be thematic –very useful, but that also

creates short comings in a printed catalogue. Shortcomings, for instance,

when ‘place of publication’ is an organising principle in the catalogue.

What we don’t have, for instance, are all the Currie editions (there are

about eight lifetime editions of Currie, the lifetime of Currie that is, and

such material is scattered throughout the printed catalogue). This is partly

because Currie is printed firstly in Liverpool, then later in London. We

often need more than one tool for a job of course, and so when I use the

Mitchell catalogue it is essential to use at least the J. W. Egerer

Bibliography of Robert Burns produced in 1964, as well as at least one 19th

century bibliography (and also these days the published catalogue of the G

Ross Roy collection in South Carolina). But to a large extent, if the

Mitchell Burns collection were to be computerised including notes

cross-referenced with Egerer and to some extent perhaps with the Roy

collection, this would make the world class collection here in this building

so much more accessible. This would be a major digital humanities project

that it would be wonderful to see the library undertake. It would require,

of course, time (including full-time staff attention) and money (which would

be worth a grant application to the Lottery Heritage fund). Here again I

speak publicly as a positively critical friend!

I offered

at the outset to reflect on some of the wider ‘cultural’ forces that have

shaped the Mitchell’s Burns collection. I’m going to attempt that task a

little bit now. As I’ve stated, the library’s holdings of the bard is built

on the important foundation of the Victorian idea of Burns collecting. Not

unrelated here, is Glasgow’s sense of itself as a great centre of culture.

Many of the traces of Glasgow as a great centre of publication are gone,

unfortunately, including the Foulis Press, printers to the University of

Glasgow. At the ‘popular’ end of the market was the firm of ‘Brash & Reid’,

one of the partners, indeed, William Reid was a personal acquaintance of

Burns (a story has gone around that Burns offered his poems to Reid before

publishing by subscription himself; we might, then, have been celebrating

the ‘Glasgow’ first edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect,

rather than the ‘Kilmarnock’ edition, though myself I think the story is a

bit dubious). When Burns is famous, Brash and Reid certainly make good money

selling Burns’s work, especially in chapbook, or little pamphlet, form.

They also do a four volume set of the poetry, probably from 1795, though

bibliographers are not entirely sure. The Mitchell has two of these sets.

Now one thing I’ve seen is Brash and Reid chapbooks of poems and songs,

sometimes including Burns along with other poets such as Robert Tannahill or

James Hogg. These don’t register in the printed Burns catalogue though

because they were presumably thought by James Gibson and by later curators

at the Mitchell not to be worth collecting particularly. So such items come

from other poetry collections held by the Mitchell. A shame a more

systematic collection had not been made earlier of these. I saw recently in

Oxford, Burns the chapbook ‘Address to the People of Scotland’ by Brash and

Reid on sale for £1,600: these are now very collectible and tell us

interesting things about the popular consumption of Burns. They were mass

produced on pretty cheap paper – so they’re disposable and so, in some

instances, comparatively rare. They would not be seen in the late nineteenth

or early twentieth centuries however or forming a proper part of a

‘gentleman’s Burns collection’: because that is largely what Gibson’s 700

volumes represent.

In terms

of pamphlets/single poems the Mitchell boasts a rare copy of the chapbook of

Burns ‘Address to the Deil’ published in 1795 by which printer we cannot be

entirely sure. On the other hand, absent from this library is the unofficial

chapbook printing of ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ the only printing of the poem

during the poet’s lifetime. It might seem ironic given Burns’s ‘folk’ and

popular associations, but the Mitchell Collection for all some excellent

subsequent collecting of chapbook materials shows, to some extent, the

unfashionable nature of popular culture until comparatively recently

(arguably until as late as the 1960s). Along with the Brash and Reid four

volume edition, however, what we have is a magnificent set of Glasgow

editions in the collection. We have the Blackie edition of 1843-44, which

carries also James Currie’s biography of the poet along with an essay by the

leading mid-Victorian Scottish critic of his day John Wilson, and also many

notes. The 1840s-50 is a time when essay and notes and appendices build up

around Burns editions, including sometimes Thomas Carlyle’s essay on the

bard. In many editions in the mid-nineteenth century it becomes difficult to

distinguish between the many voices in the one edition competing for the

reader’s attention. The Blackie editions are like that. We also have the

Bryce edition published in Glasgow, the Cameron editions – George, James,

Cameron & Co and Cameron & Ferguson and another fifteen Glasgow publishers

from the mid-19th to the early twentieth century, including, of course,

William Collins. We have too the earliest Glasgow Burns editions – the

Chapman & Lang of 1800, the Chapman and Lang and also the Thomas Duncan,

both of 1801 – these are, in effect, ‘added-to’ ‘Kilmarnock’ editions

presumably intended to compete with the collected edition of Currie, whose

1st and 2nd editions appeared in 1800 and 1801.

The most

notorious Glasgow printings of Burns are those by Thomas Stewart again

coincided to compete with Currie’s first collected works – Poems ascribed to

Robert Burns, the Ayrshire bard, not contained in any edition of his works

hitherto published (1801) – the Mitchell has five copies – and also

Stewart’s 1802 book which supplements its material with the correspondence

of Sylvander & Clarinda, something that greatly alarms Clarinda, Mrs

Mclehose, since this book is much more revealing than Currie’s edition about

the relationship of the pair. The Mitchell has three copies and also has a

rare 1803 pamphlet about Currie’s publisher’s Cadell and Davis and their

action against Stewart at the Court of Session. Apart from the Stewart

volumes the Glasgow editions tell us little about Burns we cannot find

elsewhere, but they are, as I’ve indicated, testimony to the vanished

vibrancy of the Glasgow publishing scene. What the Glasgow publications of

Burns do however boast is a vast array of illustrations which in themselves

would make for a fine research project on the reception and interpretation

of Burns’s work.

In the

twentieth century Burns pamphlets in general begin to be prized by the

Mitchell; its collection becomes much more miscellaneous. An example here is

the Glasgow pamphlet of 1903 – ‘Some Burns Collectors’. What we see from

this point is a growing awareness of the cultural hinterland that exists for

Burns studies – the ‘afterlife’ as it were, so that Burns collectors are an

interesting phenomenon in themselves, and the cultural context of the 18th

century itself, of Burns’s own times, so that the Mitchell acquires ‘Letter

from a Blacksmith’, a publication of the 1750s that stands behind the

inspiration of Burns’s poem, ‘The Holy Fair’.

The

attitude in the Mitchell from the early twentieth century that it will

collect more or less anything concerning Burns that has just been printed

has been a sound instinct – nothing much in that line is missed, and though

that might mean adding some deplorable publications to the list, even these

are part of the story: the lunatic fringe, the deluded, the frivolous, the

downright fraudulent – authors in these categories all nestle together with

the finest Burns biography and criticism in the Mitchell collection – they

are all part of the story of Burns. And talking of the story of Burns, the

Mitchell’s collection of biographies contains over two hundred authors on

Robert himself, all the way from full blow book treatments of his life to

phrenological pamphlets on the poet; over sixty biographical items on

Burns’s family; and close to another two hundred authors on Burns’ friends

and contemporaries. The collection includes twelve fiction writers (or

writers who know they’re writing fiction about the bard!) and 13 playwrights

who treat Burns. There are around 140 poets who write poems about the poet –

either in his lifetime, or subsequently. All the Burnsian inspired

contemporaries are housed in The Mitchell – Janet Little, David Sillar etc.

Not all of these are listed in the printed catalogue and if exploring you

need to cross-reference or cross-check with the hugely impressive two-volume

Scottish Poetry Collection [scarily existing only in hand-written form –

another case for digitization!]. The Mitchell has now and has always had an

excellent staff, but as so often in big libraries things have got a bit out

of hand. I’ve mentioned the Gardyne collection of poetry and other material

which is only catalogued in the most general sense. Lurking in the

subterranean stacks here, I suspect, are all kinds of lost eighteenth and

nineteenth century items which might re-emerge one day. Two things in

particular for which I’m on the lookout are the collected poems of the

Airdrie poet, William Yates – there seems to be no copy of this in existence

anywhere. And also, if possible, the 1828 Belfast edition of Burns, which

likewise seems to have vanished completely into thin air. At some point, a

physical trawl of the shelves - for several weeks – looking at books and

many bound together pamphlets and chapbooks would almost certainly bring

rich rewards. That is me being a critical friend again!

It is

interesting to see how bawdry is dealt with. I’ll come back to this in a

moment, but this tack is prompted by another publication. The library might

not have the 1789 chapbook version of ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ but it has an

1884 text of the poem printed for Kilmarnock Burns Club. Burns clubs are in

existence from a few years of Burns death of course, and in the latter part

of the nineteenth century, specifically from 1884 we have the foundation of

the Burns federation, or the World Burns Federation as it is now. The

Mitchell has of course a complete run of the often excellent Burns

Chronicle, the scholarly organ of the Federation from 1892 down to the

present day. This is another thing that the ‘average’ Burns collector can

aspire to – a complete run of the Chronicle. Anyway, the Burns clubs are

fruitfully productive of many other items of Burns publication over the past

hundred and thirty years and the Mitchell has an expansive collection of

these often highly useful publications. The previously all-male Burns clubs

could enjoy publications like ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ and such as the

Kilmarnock Club did in the 1880s, and bawdry material generally ought to be

separated in a sense from ‘popular culture’. In Burns’s own day, The Merry

Muses of Caledonia which the poet certainly collected in its original form,

was something for the gentleman for the weekend! This perhaps explains the

excellent collection of The Merry Muses under this very roof. It includes

the ‘1827’, really the 1872 (indeed two copies of same), the privately

printed Burns federation privately printed ‘edition’ of 1911 (two copies) in

which Duncan McNaught attempts to prove that Burns had very little to do

with the contents – talk about having your cake and eating it! The 1959 &

newly legal 1965 James Barke & Sydney Goodsir Smith edition are there, as is

the 1965 Legman and 1966 Randall editions. There is also the excellent G

Ross Roy facsimile version from a decade back – based on the Roy collection

volume – the only one of a handful of extant copies of the original of 1799

to contain a complete title page. No surprise that James Gibson didn’t have

one of these – also no surprise that he DID have the so-called ‘1827’. I

need to do some work on the original 700 Gibson volumes which form the rump

of the Mitchell collection to determine the shape of a ‘gentlemen’s

collection’ and also to be a wee bit more precise about the Mitchell’s

acquisitions policy thereafter. A librarian of 1890 or 1920 or 1945, or a

collector such as Gibson himself would be surprised that their own practices

might become an object of investigation, but these are, indeed, a revealing

part of cultural history, of book-history, in the present case of the

history of the Mitchell Library.

In terms

of criticism, the library has every major monograph, collection of essays

etc. since the nineteenth century, especially from the first 1860s Regius

Chair of English at Glasgow, John Nicholl to the current one, Nigel Leask.

The Mitchell also has very good newspaper cuttings relating to Burns through

the nineteenth century and into the last one. Likewise, it has some great

sound recordings of Burns songs, but the collection here is very far from

comprehensive. Arguably, neither of these last two things matter so much in

this day and age of the web and internet when so much now is retrieved that

way.

So what do

we have under this roof? A print collection of Burns that is unsurpassed or,

if at all, not by much and maybe only by the print holdings at the Thomas

Cooper Library, South Carolina. It is wonderful that the world has both

these collections. The Mitchell has a small but unique set of highly

valuable manuscripts and Burns biography, criticism, translations and

miscellanea that is as ‘great’ as anywhere in the world. It is truly a

world-class collection, but there is a challenge ahead – the challenge, at

the very least, to maintain and make it more accessible. The Mitchell is the

greatest publicly, or most openly, accessible Burns Collection in the world.

The Mitchell should not, says this enthusiastic, admiring ‘critical friend’,

sit back – ideally it needs to collect more manuscript material as and when

it can, and it needs to digitize its catalogue and maybe also begin

digitizing its holdings too. The Mitchell, Glasgow, the west of Scotland,

Scotland, Britain, Europe, the World has a treasure in this Burns collection

– which needs to continue to shine out brightly and that requires continued

hard work! |