|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

It

has been much too long since the writings of Dr. Kenneth Simpson have graced

these pages. One of the kindest and most polite men I have ever known, an

undisputed Burns scholar, as well as a talented writer, scholar, author and

speaker, it is wonderful to welcome my good friend back to Robert Burns

Lives!. Among my favorite books written on Burns are two edited by Ken:

Love & Liberty and Burns Now.

In

this article Ken reviews The G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns: An

Illustrated Catalogue which first appeared in the

Scottish Literary Review edited by Sarah Dunnigan and Rhona Brown who

edits the reviews section. Thanks to them for allowing the review to appear

on our web site.

By

way of introduction to Ken’s review below, I take great pride in sharing a

blurb I was asked to write for this book:

“This eagerly awaited publication will be a joy for all serious Burnsians

since there has been no major Burns catalogue in recent times. It is a

useful research tool by the world’s most preeminent Burns scholar. Ross

Roy’s comments and illustrations regarding the rarer items make this great

collection even better for all who wish to study the Scottish bard. This

book will be of special value as a guide to the major Burns collection in

North America.” (FRS: 5.25.11)

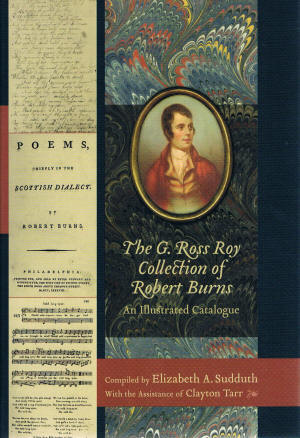

Book Review

By Dr. Kenneth Simpson

of

The G. Ross Roy Collection of Robert Burns: An Illustrated Catalogue

Compiled by Elizabeth A. Sudduth With the assistance of Clayton Tarr

Introduction by G. Ross Roy

Foreword by Thomas F. McNally

Published by The University of South Carolina Press

in cooperation with the Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina,

2009

Arguably pride of place in the G. Ross Roy Collection should go to the

edition of Burns inscribed ‘from his friend, Charlotte A. Sprigings, Xmas

1890’ to W. Ormiston Roy. The gift exchanged between Professor Roy’s

paternal grandparents initiated the collection begun by W. Ormiston Roy and

greatly enlarged by his grandson, so that it now forms the most extensive

collection of Scottish books and manuscripts outwith Scotland. The Burns

material here catalogued comprises a third of the collection.

In

his Introduction Dr. Roy acknowledges that since the publication in 1964 of

J.W. Egerer’s Bibliography of Robert Burns he has been ‘on a chase to

obtain a copy of every volume listed’. Few have eluded him. This Burns

cornucopia includes Kilmarnock and Edinburgh editions; one of only two known

copies of The Merry Muses of Caledonia (1799) – ‘by far the most

important eighteenth-century volume in the collection’ in Roy’s view; a

wealth of songbooks and chapbooks; several interesting Burns letters; a

Miers silhouette of Clarinda with a lock of her hair; and items such as a

recording of J. Ramsay MacDonald, ‘Robert Burns, a Man Amongst Men’, the

1937 movie, Auld Lang Syne with Andrew Cruikshank as the Bard, and

Burns’s porridge-bowl and spoon. Courtesy of the W.Ormiston Roy Research

Fellowship, scholars have been afforded access to such materials; and the

University of S. Carolina has a distinguished record in hosting

international conferences on Scottish literature. Rightly Thomas F. McNally

in his Foreword claims for the University’s Thomas Cooper Library ‘a

distinctive research strength in Scottish literature…unrivalled in North

America’; and, since the catalogue is now online, access is available to

all.

Appropriately published in 2009, this illustrated catalogue is the most

valuable of the many Burns books of that year. This is a book to be read,

rather than merely consulted: it opens up so many roads to, and from, Burns.

The chronological order of publication in the first two sections –

‘Manuscripts and Typescripts’ and ‘Printed Materials, Books, and Sheet Music

by Burns’ - fosters awareness of movements in taste, fluctuations in Burns’s

reputation, and – above all – publishing history. For selected major items

Roy offers informative annotations: the expansion of the five-page glossary

of the Kilmarnock edition to twenty-five pages in the Edinburgh indicates

the ever-increasing range of Burns’s readership; it is helpful to be

reminded that ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ first appeared in a chapbook in 1789;

and a promissory note by Burns shows that ‘in late eighteenth-century small

towns, handwritten drafts and IOU’s substituted for more formal banking’,

hence some of the poet’s financial problems are contextualised.

Inscribed editions of Moore’s Zeluco, Thomson’s The Seasons,

and Cumberland’s The Observer reflect Burns’s range of reading; and

marginalia testify to his boast in a letter, ‘I would not give a farthing

for a book, unless I were at liberty to blot it with my criticisms’. Various

items give insight into Burns’s methods of composition and the contexts

thereof: on the manuscript of ‘Lesley Bailie: A Scots Ballad’ the poet

writes, ‘the foregoing Ballad was composed as I galloped from Cummertrees to

town, after spending the day with the family of Mayfield’ (surely there is a

thesis to be written on Burns’s trotting, cantering, and galloping poetic

rhythms?); a poem to Syme is written at the ‘Jerusalem Tavern, Dumfries,

Monday even’; and – a wonderful irony which Burns must have relished – ‘An

Address to the Unco Guid’ is inscribed on the endpapers of a published

sermon, Thomas Randall’s Christian Benevolence.

Some of the biographical issues which currently preoccupy Burnsians are

represented. Was Burns serious about emigration? Burns’s farewell letter –

‘my last this side of the Atlantic’ - to Thomas Campbell, August 19, 1786,

might seem to settle the matter until one realises that it predates both

Jean Armour’s giving birth to twins and Thomas Blacklock’s recommending a

second, enlarged edition of the poet’s work. There is material aplenty

relating to the Edinburgh sojourns, influential in a variety of ways on the

poet’s career: a newly recovered letter from Clarinda speaks for Burns’s

personal life; proof-sheets of ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ with Alexander Fraser

Tytler’s marginal emendations betoken the influence of the literati. Burns’s

life is here contextualised in the context of his age and its values. The

contemporary concern with the relationships between primitive and modern

societies and cultures is typified in Tytler’s translation for Burns of part

of Lucan’s Pharsalia concerning the Druids and human sacrifice; and

the poet as Man of Feeling is revealed by what appears to be the shedding of

the requisite single tear upon a letter to Clarinda.

Susan Shaw and

Ken Simpson walking in Dumfries

The catalogue also provides a useful index both to Burns’s popularity and to

the ways in which he came to be viewed and used. It is comforting to know

that for those for whom the cost of a Kilmarnock or Edinburgh edition was

prohibitive there was still access to Burns through chapbooks. It is

salutary to note that ‘To a Mountain Daisy’, a poem little in favour now,

was included in 1794 in The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Poetical Preceptor:

Being a collection of the most admired poetry selected from the

best authors. Similarly, the frequency of nineteenth-century printings

of ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ attests to the selectively didactic use of

Burns. An edition of Burns’s Works is inscribed, ‘Marmaduke Head Best

with the best wishes of Robert Sheppard Routh, On his leaving Eton, Easter

1864’; Logie Robertson’s edition, Selected Poems (1889) bears the

bookplate of Edinburgh Ladies College; and Valentine & Sons printing of ‘Tam

o’ Shanter’ (189-?), complete with original tartan covers, is inscribed

‘with best wishes from Aunt Jeannie’. That Burns came to be identified with

‘Scottishness’ is variously testified: Burns is anthologised in Heather

Bells (London; Paris, New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons [ca. 1900]) with a

frontispiece, ‘The Bairn’s Breakfast’ by H.J. Dobson; in Glasgow and New

York in 1903 appeared Guid Bits frae Robert Burns. Witty, humorous,

serious, pathetic & pithy; and a presentation copy of ‘The Cotter’s

Saturday Night’ to Sir Harry Lauder has two poems inscribed on the

preliminaries – ‘In Robbie Burns o’ deathless fame’ and ‘Address to Harry

Lauder’. As counter to couthiness the various translations – Russian,

Japanese, Portuguese, Gaelic, and others – indicate that Burns reaches all

corners of the globe. The many whom he inspired include Robert Tannahill,

with whose songs Burns’s were often reprinted; the freed slave, Frederick

Douglass; the artists, John Faed and Thomas Landseer; and the poet and

dramatist, Tom Wright, whose play, There Was a Man, did so much to

further popularise Burns in the nineteen-sixties and seventies.

Materials vital to Burns scholarship abound in this collection – five

letters from Cromek to Creech in 1808; Agnes McLehose’s letter to Cunningham

reiterating the embargo on access to Burns’s letters to her; Isabella Burns

Begg’s letter referring to Jean Armour in unflattering terms; and the

research manuscripts of major Burns scholars such as J. DeLancey Ferguson,

Robert H. Thornton, and G. Ross Roy.

As well as enlightenment, this catalogue offers entertaining

moments. Celebration of the 111th

Anniversary of Robert Burns’ Natal day, at Delmonico’s Hotel, New York,

January 25th,

1870 sounds promising; one longs to have been in the audience when the

‘Eastern-Empire Lyceum Bureau present[ed] The Scottish Musical Comedy

Company in an Original Adaptation of Robert Burns’ “The Cottar’s Saturday

Night”’; and James Findlay, Burns in Heaven: Suggested When Looking at

Burns’ Statue, Union Terrace, Aberdeen (1908) tantalises.

Elizabeth A. Sudduth is to be warmly congratulated and thanked. This book is

a Herculean achievement, the result of what must often have seemed a

Sisyphean endeavour. The catalogue records the contents of this outstanding

collection to July 2008. Dr Roy writes that he continues ‘scouring dealers’

catalogues and the Internet for more titles’. Charlotte A. Sprigings

certainly started something! |