|

Edited

by Frank R. Shaw, FSA Scot, Dawsonville, GA, USA

Email:

jurascot@earthlink.net

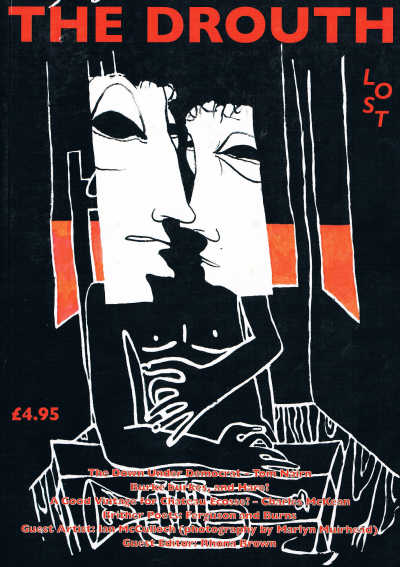

Cover of the Winter 2009/10 issue of THE

DROUTH is used with permission of artist Ian McCulloch. The image is

of McCulloch's painting 'The Brothers' (2009) which was included in his solo

show at the Collins Gallery, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

One of my favorite Scottish journals is THE DROUTH, and one of the

reasons I enjoy it so is because its two editors, Mitchell Miller and Johnny

Rodger, write and live on the cutting edge of Scottish life. THE DROUTH

also has a guest editor for each issue and for the Winter 2009/2010 volume

it was none other than Dr. Rhona Brown who has written two articles for

Robert Burns Lives!, both concerning the man affectionately known

as the Chairman of the Bard, Professor G. Ross Roy.

One of the major contributors to THE DROUTH is Dr. Gerard Carruthers

whose contributions are usually about one person – Robert Burns. Thus,

“Robert Burns and the Excise” which appeared in the above mentioned issue of

will now grace the pages of Robert Burns Lives! thanks to the writer

and editors who have consented for it to appear on our web site as the 102nd

chapter or article about Burns. Little did I know when I started editing RBL

a few years ago that so many would be so willing to contribute to its pages.

A

lot has been written about Burns the exciseman, some of it good, some of

it…well, you finish the sentence. This is an excellent piece, and over lunch

recently at the University of South Carolina, two of the people who should

know the good from the bad and the ugly pronounced it very good! Thank you,

Drs. Robert Crawford and Patrick Scott. And, I offer my thanks on behalf of

our readers for such a quality example of writing by Dr. Gerard Carruthers.

(FRS: 11.22.10)

Robert

Burns and the Excise

By Gerard Carruthers

Dr. Gerard Carruthers speaking at the Burns Club

of Atlanta, April 2010.

Picture courtesy of William Tucker, editor of BCOA Newsletter.

I do not

know if I have informed you that I am now appointed to an

excise division, in the middle of which my house and farm lie. In

this I

was extremely lucky. Without ever having been an expectant, as they

call their journeymen excisemen, I was directly planted down to all

intents and purposes an officer of excise; there to flourish and

bring forth

fruits — worthy of repentance.

I know not

how the word exciseman, or still more opprobrious,

gauger, will sound in your ears. I too have seen the day when my

auditory

nerves would have felt very delicately on this subject; but a wife

and

children are things which have a wonderful power in blunting these

kind

of sensations. Fifty pounds a year for life, and a provision for

widows and

orphans, you will allow is no bad settlement for a poet. For

the ignominy

of the profession, I have the encouragement which I once heard a

recruiting sergeant give to a numerous, if not a respectable

audience, in

the streets of Kilmarnock.— “Gentlemen, for your further and better

encouragement, I can assure you that our regiment is the most

blackguard

corps under the crown, and consequently with us an honest fellow has

the

surest chance for preferment.i

So

wrote Robert Burns to his close friend, Robert Ainslie, on 1st

November 1789 on becoming newly commissioned as a Crown employee. As so

often in Burns’s biography we find the poet expressing an ostensibly awkward

location for himself with a certain amount of glee. One of the grand themes

in Burns biography is the poet being in places and situations he shouldn’t

really be, located where he’d rather not be. The dislocation of Burns is

read, fairly obviously, in the idea of the ‘heaven-taught ploughman’. We see

this often in his public career. Notoriously, Henry Mackenzie’s epithet

removes Burns from the tradition of eighteenth century Scots poetry, to say

nothing of eighteenth century English poetry, in which he properly belongs.

Burns himself of course, prompts the idea of untutored rusticity,

encourages, plays along with this. Depending on how one reads Burns

collaboration with the idea that he is principally inspired by nature rather

than literature, rather than art: then this is either a clever marketing

ploy on Burns’s part, or a desperate strategy where he realises that

Enlightenment Scotland will be receptive to his primitive novelty, but much

less so to the idea of a real writer of cultural polish emerging from rural

Ayrshire. We find numerous other instances of the idea of Burns as a man out

of kilter with the world as it honestly is, out of kilter with the man he

actually is. With some justification Burns’s Edinburgh year and a bit from

1786-87 is read as representing a somewhat unreal time for the poet. Burns

is lionized in the Scottish capital, but not truly accepted: he tires of

life in the metropolis eventually and settles down in Dumfriesshire. His

letters speak of real disillusionment with the literati who had enjoyed him

for a season, but they also speak also of self-disgust. The fact is that

Burns had enjoyed himself in the Edinburgh period, conversing, drinking,

carousing with aristos, with middle class individuals and with distinctly

down at heel acquaintances. One friend he retained from Edinburgh was Bishop

John Geddes, to whom he wrote from his new farm in Ellisland in February

1789, where he implies that he has frittered away his time in licentious or

at least flippant pursuits. He will now, he tells the prelate, ‘attend to

those great and important questions, what I am, where I am, and for what I

am destined.’ii

In the same letter he expresses satisfaction with his wife and his new farm.

What we have, then, is a serious-minded, philosophical, monogamous Burns,

savouring the simple-life, the hard-working life. Precisely, given that it

is to a Catholic prelate, Burns’s letter is confessional. In the same

epistle, he reflects on his new life as a Crown employee:

There is a

certain stigma affixed to the character of an Excise-Officer, but I do

not intend to borrow honour from any profession; and though the Salary

be

comparatively small, it is luxury to any thing that the first twenty

five years of my

life taught me to expect.iii

As

so often in his letters, here Burns strikes a pose; and as I say this I

don’t necessarily mean to accuse Burns of ‘insincerity.’ But in one sense

Burns is posing to his correspondent, because Burns is writing to someone,

Geddes, whom he admires morally as much as any other individual he had ever,

or would ever, met. He wishes to match in himself what he takes to be the

moral stature of Geddes; there is a sincere reaching out to Geddes. But this

sincere moment is, arguably, undermined by Burns’s conduct, certainly so far

as monogamy is concerned both before and after this letter. More than

striking a pose towards Geddes, however, Burns is striking a pose towards

and for himself. This is a Burns of sincere, new resolution which he won’t

entirely live up to. So far, so typical of human nature: how like any of us.

The point I’m simply making to begin with is that poor old Burns is open to

judgement in a way few of us are – his self-deception, his ruined good

intentions, his moral inconsistency is pored over in a way these same things

will never be in most people’s lives. That’ll teach him for being a great

writer, for being the national poet of Scotland! The other thing I’m getting

at is the idea that Burns never quite finds the right place to be. And that

this is a disaster for him, and also speaks badly for Scottish culture: that

Burns is never properly located. I want to suggest that this is an

over-determined, over-driven idea that has meant that many, if not all,

Burns biographies are ridiculously crude. The idea of fixing the man, fixing

the personality is a rather old-fashioned idea, it is the idea of biography.

But biography, arguably, is a very stupid practice.

Here I want to focus on one ‘biographical area’, indeed one cultural context

for Burns, his employment as an excise-man. A powerfully simple observation

to start with is that among Burns’s parcel of schooling was mathematics and

surveying (to say nothing of French and Shakespeare!). William Burns was

ambitious for his children.iv

As his shifts between farms, at his own behest and in accordance with the

wishes of landlords, life on the land was precarious. Might there be

something a bit better for Robert? Even Flax-dressing represented a more

stable living than farming as shown by the poet’s apprentice-time at this

trade in Irvine in 1781. Clearly, Robert, or his father on his behalf was

early on looking beyond the family trade. Other options a little later (in

1786) included Burns’s desire to find work in the slave plantations of the

West Indies, where Burns’s book-keeping skills would come in handy? Becoming

a man of letters, as he clearly tried to be in Edinburgh, might this bring

in the money? It did to some extent, but in a combination of his own

carelessness and the tight-fistedness of book-seller William Creech,

Edinburgh was not as profitable as it might have been for Burns. Some money

remained over from selling his poems in Edinburgh to be invested in what he

knew: a farm. But Robert, probably bearing in mind the experiences of his

father, wanted another string to his bow: the Excise service. This is a

rather peculiar choice of occupation for a man working, or at least owning a

Dumfriesshire farm. Excise men were fairly roundly hated, most especially in

the countryside where they’d be involved in smashing illicit distilling and

interfering with the smuggling ‘industry’, which was the second string to

the bow of quite a number of ordinary folk. New luxury goods, including tea

and tobacco, were made accessible to ordinary folk who obtained these free

from the prohibitive prices that were attached to them with taxation. As

well as this, at a time of subsistence living and some seasons of

near-starvation, or at least very basic and tedious diet, smuggling allowed

substantial numbers of people to be entrepreneurial, either smuggling

themselves, or at least acting as middle-folk for contraband goods. It

allowed participation in a commercial economy (albeit a black one) when

these people had no access to any other kind. Smuggling in short allowed a

degree of economic mobility to the lowest classes.

In

his letter to John Geddes, Burns refers to the ‘stigma attached to the

Excise’; what he means is that this places him somewhat beyond the pale,

hated by the common man, by the ordinary folk. We see this kind of taxman in

the Gospels, and we find it still in eighteenth century Scottish life. In

the general register and tone of the Geddes letter Burns, is probably

consciously aware of the image of the taxman in Christian scripture, and

with typical wit also paints the Excise service as a kind of penance.

Actually, of course, at the same time as relishing his new ‘sober’,

monogamous state, as he does in his letter to Geddes, Burns is also

relishing the Excise. It should be remembered too that Burns enjoys playing

the outcast at times (he is a man of many simultaneous guises).

Three years into his career in the Excise, in 1792, Burns penned the song,

‘The Deils’s awa wi’ th’ Exciseman’:

We’ll mak

our maut and we’ll brew our drink,

We’ll laugh, sing, and rejoice, man;

And mony braw thanks to the meikle black deil,

That danc’d awa wi’ th’ Exciseman. (ll.9-12)v

Our writer knows he’s spoiling folk’s fun, to some extent even spoiling

their livelihood. The humour in this song is darker than is usually

realised. Last November I was speaking to Thornhill Burns Club, and the

excellent Secretary of that club, Ian Miller was regaling me with stories

from oral memory of the unpopularity of the exciseman, including Burns, in

Dumfriesshire. There are some hints in the biographies about Burns being

shunned by the good citizens of Dumfries, and it might be thought that the

reason has to do with drink (in an old-fashioned biographical canard), or

adultery. However, the area exciseman more potently and directly than any

justice of the peace or town burgess at this time represents central

government authority like no other individual. Here is one place (and not

the only one) where we might well heretically realise that Burns is most

certainly not ‘the poet of the people.’

In

spite of some study of the situation, we still know too little, will perhaps

never know very precisely some of the crucial particulars of Burns’s excise

career. There is a rather silly myth of conspiracy: that the government was

out to destroy Burns, and that various individuals answerable to the office

of Henry Dundas (‘ruler of Scotland’ in the 1780s and ’90s) decided that a

career in the excise was a good way of ruining Burns’s health – ride him

hard (and often he was riding hard and long, like many Excise men especially

in the rugged Scottish countryside), and put him in an early grave.vi

Like most conspiracy theories, this falls at the first hurdle. Burns it was,

very evidently, who sought out Robert Graham of Fintry, Excise Commissioner,

to apply for the service. Burns saw Fintry as a gateway to salvation rather

than ruin: ‘Fintry, my stay in worldly strife,/Friend o’ my muse, friend o’

my life’.vii

In his ‘Epistle to Graham’, Burns expresses the energy of his excise rides,

as he situated this energy in the context of his imaginative productions. In

effect, his excise horse becomes Pegasus:

Come then, wi

uncouth kintra fleg,

O’er Pegasus I’ll fling my leg (‘Epistle to Robt Graham’, ll.4-5).

‘Kintra fleg’: country fling. It was sometimes exhausting for Burns in the

excise, but he sometimes also enjoyed it. One other aspect of ‘kintra fleg’

was that it allowed him to enjoy song-collecting and writing, for which he

had much more space and leisure than if he had been solely and personally

devoting himself to the matter of Ellisland farm. Burns, perhaps before, but

certainly during the 1790s becomes passionately lost in the art of song in a

way that surpasses his relationship with poetry.

Under-estimated by biographers is how much Burns enjoys himself in the

1790s, in his period of employment in the Excise and even, one might dare

venture, when he becomes also a member of the Dumfries Loyal Volunteers. As

in the case of his membership of the local militia, Burns and the Excise

inevitably involves discussion of politics. For Burns, we are told by some

commentators, the excise service represented a compromised space for the

poet. There is some evidence of this but before turning to it, we should

also consider an aspect that is almost never mentioned, and which Burns with

his usual astuteness would have been well aware. If sometimes unpopular with

the people, the exciseman enjoyed also, to some extent, an iconic status as

a double-dealer, and by that I do not just mean as someone on the take, or

open to bribes. Actually, there was a strong of tradition of political and

economic radicalism standing behind the recent figure of the exciseman in

Burns’s time. Palpably, the exciseman might be a beacon of economic and

political liberty. This is the case for two individuals of whom Burns would

undoubtedly have been strongly aware. We don’t have any direct evidence that

Burns read the works of the most famous of all taxmen in the late eighteenth

century: Thomas Paine. Burns must have known his ideas, however, just as he

must have known the work of the Scotsman James Thomson Callender, who like

Paine eventually had to flee into political exile, was clerk in the Sasine

office in Edinburgh dealing with feudal dues from where he developed an ever

more radical bent. Like Burns a poet, Callender was a powerful dissenting

voice in Scottish journalism from the late 1780s, whose The Political

Progress of Britain (1795) employed his mastery of arithmetic to show

that Britain was unfair in its allocation of material resources, as well as

wasteful. Paine and Callender both believed that Great Britain was run on

illogical economic principles, not least in its system of taxation. Both men

were led into political radicalism to a great extent by their careers in the

civil service. Callender believed that extending the franchise, or greater

democracy would see not only a more just, but also (indivisibly) a more

efficient economic arrangement. So, Burns had good examples of culturally

radical taxmen, even if he himself was less outspoken than those two just

mentioned.

Of

course, Burns swore to end meddling in politics when apparently questioned

by his superiors in the excise about his political allegiances following the

French Revolution. He indicates in a letter of 1792 that he has been accused

of suspect politics, protests his innocence and eventually his patron Graham

of Fintry writes to him in support and later helps exonerate the poet.viii

Supposedly there was (in portentous terms) a ‘board of inquiry’ but very

little is known about this, and one is bound to wonder if it is all that

serious since there is such scant documentation. Burns, clearly, is relieved

when the incident is over, and well he should be as a government man. But is

there a touch of melodrama in Burns’s account (even, one might ask

heretically) of wanting to play the radical? Charges of sedition, being

scattered around all too easily at this time, seem never to have been

remotely close to being brought against Burns. Rather easily, Burns is free

from any comeback, and, indeed, goes on in a couple of years to promotion in

the excise.

The other great episode in Burns’s civil service career involves the

notorious seizure of the smuggling brig, the Rosamund, in 1792. Undoubtedly,

Burns and his colleagues were involved in raiding and impounding the vessel,

but Legend has it that Burns bought the four carronade (six pounder guns)

seized from the ship when these were auctioned off and sent them to the

Jacobins in France. Actually, as an article in the Burns Chronicle in 1992

more wisely speculates, these were probably bought by another smuggler for

another smuggling vessel. Apologists for the myth say that Britain was not

yet at war with France, as it would be in a year or so. True, but a

government employee would need to be rather silly not to see the way the

wind was blowing and risk his career in such risky fashion. In fact, it

seems to be John Gibson Lockhart, Burns early nineteenth century Tory

biographer who first promulgates the story. Albeit that he was acting on

legends supplied by others, the notoriously unreliable ‘Honest’ Allan

Cunnignham, a man who attempted to pass off on the world a considerable

number of spurious songs as being by Burns, and another exciseman Joseph

Train very keen to pass on Burns-lore over which a great deal of doubt may

be riased. In very basic terms, Burns’s salary of over £50 was not conducive

to allowing him to buy the guns which were offered for sale at over £4. Why

not just send the money to the Jacobins? They could have purchased these

guns just as easily for themselves in their own country, and Burns could

also have thrown in the additional expense, legend has it, that he made in

transporting these guns down to Dover and then across the English channel.ix

Walter Scott, perhaps mistrusting his son-in-law Lockhart (or at least

Lockhart’s sources) enquired of the customs receipts and permissions at

Dover that would have needed to have been completed for all this to have

happened, and was able to find no documentary verification.

Very briefly I want to animadvert on a recent book of copious sentimental

drivel, the melodramatically titled, The Patriot Bard. This tome

mangles evidence in support of its claim that Burns was a member of the

reformist society, the Friends of the People during the 1790s. There is, in

fact, not only no proof for any such membership, but a strong degree of

improbability. A recent essay by Mark J. Wilson demonstrates the egregious

errors of The Patriot Bard.x

Burns would have been extremely stupid, no matter what his political views

were (and perhaps especially so, if he was an out and reformist – and I

believe he was) to have joined the Friends of the People. The poet had taken

an oath of loyalty to the Crown when joining the Excise. He was to take

another when he joined the Dumfries Militia. Now the point of this is not

that Burns was an irredeemable government loyalist, but that he was, at

least, relying on the government for his bread and butter and in joining the

militia he was maybe signalling also that he didn’t much like the idea of

foreign invasion – from France or anywhere else – military invasions by

foreigners almost never bring any good. The excise was an opportunity for

Burns – financially, in terms of getting away from Edinburgh, in terms of

helping allow him space as a song-smith. It also provided something of a

pension for his widow and orphans, which he himself saw as part of its

attraction. The excise was also in general one of many imaginative spaces

that Burns occupied: a site of pride, enjoyment, playfulness, contradiction

and unpopularity – like so many of the social and cultural spaces that he

occupied in his life. To a large extent, it was very much an occupation of

choice for Burns. It was his choice. It is time (some) Burnsians

stopped their special pleading over this part of Burns’s biography.

i

R. H. Cromek, Reliques of Robert Burns Consisting Chiefly of Letters,

Poems, and Critical Observations on Scottish Songs (Cadell & Davies:

London, 1813) [Second Edition]. pp.99-100.

ii

J. De Lancey Ferguson & G. Ross Roy (eds.), The Letters of Robert

Burns Volume I, 1780-1789 (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1985), p.366.

iii

The Letters of Robert Burns Volume I, 1780-1789, p.367.

iv

I am grateful to Professor Nigel Leask for this point.

v

James Kinsley (ed.), The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns II

(Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1968), p.656.

vi

For a lurid and entertaining fictional version of this scenario which

some credulous, unwary individuals believe to be essentially true see

Alistair Campsie’s novel The Clarinda Conspiracy (Mainstream:

Edinburgh, 1989).

vii

James Kinsley (ed.), The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns II,

p.549.

viii

See Burns’s alarmed letter to Robert Graham of 31st December

1792, and his correspondence with Graham and others over the next

several months; no biographer of Burns gives a particularly penetrating

account of this whole episode.

ix

For a fuller account of this episode see Gerard Carruthers & Jennifer

Orr, ‘The Deil’s Awa’ wi’ the Exciseman’ in Johnny Rodger & Gerard

Carruthers (eds.), Fickle Man: Robert Burns in the 21st

Century (Sandstone Press: Dingwall, 2009), pp.257-266.

|