|

THE Act of 1872, as an

outstanding feature in the history of education, has been dealt with as the

starting-point of our fourth school period from that date to the present

time. The Act of 1858, as conspicuous for its influence on university, as

that of 1872 on school life, has been chosen as the commencement of our

fourth university period.

There are two great landmarks

in the history of the Scottish universities, the remodelling which they

underwent in 1858 and again in 1889. Before 1858 in all the universities,

except Edinburgh, the administration was in the hands of the Senatus

Academicus. In Edinburgh it was largely in the hands of the municipality.

The commissioners of 1858 were instructed to have special regard to the

several reports which followed the visits of the commissions between 1826

and 1857. These instructions were faithfully carried out, and resulted in

the excellent Act of 1858, which may be said to have nationalised the

Scottish universities. The ordinances passed under it practically regulated

the action of them all for more than thirty years.

By the Act of 1858 larger

powers were given to the Senatus, and the University Court and General

Council were instituted. Henceforth in Glasgow and Aberdeen the Rector was

as hitherto elected by the matriculated students divided into four

'nations,' but in Edinburgh and St Andrews in such manner as the

commissioners might determine. The functions of the faculty were divided

between the Senate and the University Court. To this Court, consisting of

the Rector, Principal (and in Edinburgh the Lord Provost, in Glasgow the

Dean of Faculties), and four assessors, was transferred the appointment of

professors. It is more correct to say that the Crown's patronage was

retained, and that the Town's went to the Curators. The Court had charge of

the revenue and pecuniary concerns generally, the regulation of fees, and

internal arrangements. The General Council consisted of the Chancellor,

University Court, the professors, graduates and others who had attended four

sessions [As graduation had (except in Aberdeen) gone much out of fashion,

registration in the General Council was granted to all who had, prior to

1861, completed four sessions, at least two of them being in the Faculty of

Arts.]. It met twice a year and made representations to the Court on any

questions affecting the welfare of the university. By the Ordinance of 1858

bursaries were revised, new professorships were founded, and provision was

made for assistants to professors and examiners for degrees. The order in

which classes were to be taken was left to the student's choice, and the

subjects of examination for degrees were arranged in three departments in

Glasgow and Edinburgh, but in St Andrews and Aberdeen there were four

departments, chemistry being compulsory in the former, natural history in

the latter. The subjects might be taken in any order, the result of which

was a large increase in graduation and in the number of students.

This concession to individual

tastes and requirements, while necessary and in some respects desirable, was

by many thought to be not an unmixed good, inasmuch as it affected

injuriously the unbroken social intercourse that formerly existed among

young men engaged in common pursuits and studies during their residence at

the university [University of Glasgow Old and New, XXV - XXVI ]. The

experience of thirty years and the investigation of the commission of 1876

brought to light a number of facts clearly suggesting the expediency of

further legislation.

One of the aims of the Act of

1858 was increase of graduation, and giving to graduates, through their

General Councils, an interest, and, to that extent, a share in university

administration. Through the institution of University Courts, the somewhat

close professorial atmosphere was freshened and vitalised by a wholesome

current of ventilation from without. Other aims were increase of professors'

emoluments and the appointment of assistants and additional professors. On

this subject the municipal origin of the University of Edinburgh

necessitated exceptional treatment. The appointment to professorships, which

up to this time had been in the hands of the Town Council, was now to be

transferred to the University Court. In this matter the Town Council had

used their power on the whole well, and naturally objected to its being

taken from them. But in view of the squabbling between the municipality and

the Senatus which, with faults on both sides, had characterised a

considerable part of the 18th and 19th centuries, and which sectarian

feeling, aroused by the ecclesiastical disruption of 1843, would tend to

foster while interfering with wholesome administration, a moderate check on

the autocracy of the Town Council was thought desirable. A compromise was

accordingly adopted which assigned the patronage of the university to seven

curators, four of whom were to be nominated by the Town Council, and three

by the University Court.

It was certainly better that

the influence of the Town Council in making appointments to chairs should be

exercised in this way than by compelling candidates to canvass thirty

representatives of city wards. It was further ordained that the Rector was

to be elected by the students, and the Chancellor by the graduates or

General Council. In the House of Commons a permissive clause was proposed by

Mr Gladstone that the four universities should take the form of `colleges'

of a central university, which should conduct examinations for all Scotland

in a way somewhat akin to the London University. Some approved of this as

tending to secure uniformity of attainment and stimulate effort on the part

of both professor and student. The House of Lords thought it an innovation

undesirable on the ground of sentiment and tradition. As it was only

permissive it was allowed to remain part of the act.

A powerful executive

commission was appointed to carry out the purposes of the act. It was

entrusted with large powers which, injudiciously used, might have worked

ruin, but the interests of the universities were safe in the hands of such

men as the Duke of Argyll, Earls Stanhope and Mansfield, Lord President

McNeill, Stirling of Keir, Lord Moncrieff, and, most important of all, the

sagacious and energetic Lord Justice Clerk Inglis as chairman [" They acted

with the greatest wisdom and sagacity, and produced a system under which the

universities, and especially the University of Edinburgh sprang into new

life and development." Grant's .Story of Edinburgh University, II, p. 100.].

A proposal that principalships should not be confined to ministers of the

Established Church was carried. Of this change Sir David Brewster as

Principal of Edinburgh was the first fruit. In due course they proceeded to

frame regulations for graduation in medicine and arts, arranging for three

classes of medical degrees-Bachelor of Medicine (M.B.), Master in Surgery (C.M.),

and Doctor of Medicine (M.D.). For the two lower degrees compliance with

Ordinance 5, which was merely supplementary to the arrangements adopted in

1833, was necessary. For M.D. the requirements were a lapse of two years

after the lower pass, age not less than twenty-four, and proof of

satisfactory attainments in the Faculty of Arts. The medical faculties in

their jealousy of extra-mural teaching made a protest against Ordinance 8

which sanctioned it, but without effect, and both ordinances were confirmed

in 186I. In 1866 the production of a thesis on some medical subject was

added, as necessary for the degree of M.D. Under these regulations, the

number of students and graduates in medicine rapidly increased till 1890,

when it fell off for about ten years and again increased. In the Faculty of

Arts the Commission of 1858 did not adopt the recommendation of the Royal

Commission of 1826-30 as to an entrance examination, but they instituted a

voluntary examination for a three years' course, and an examination testing

fitness for promotion from a junior to a senior class. They abolished the

system of B.A. and M.A. Of 1826, and also the B.A. instituted by the Senatus

Academicus in 1842, which was simply M.A. with the omission of some

subjects. Instead of this they established only one M.A. degree which could

be taken in three stages.

This was adopted to encourage

graduation and enlarge the General Council. It had this effect, and infused

a general spirit of work into the various classes. The subjects covered by

the Arts course were Latin, Greek, mathematics, natural philosophy, logic,

moral philosophy and rhetoric. For the ordinary M.A. degree examination in

these seven subjects was necessary.

Honours might be taken in

each of the following departments: (1) classical literature; (2) mental

philosophy, including logic, metaphysics, and moral philosophy; (3)

mathematics, including pure mathematics and natural philosophy, and (4)

natural science, including geology, zoology and chemistry. In each of the

first three of these departments, there were two grades of honour, but in

natural science only one [In St Andrews and Aberdeen Science was an eighth

compulsory subject. ].

While attendance at the

classes of these seven subjects was necessary for degree, it is scarcely

doubtful that the pitch of the examination was not high, but considerably

higher than that of Cambridge or Oxford even now. The scarcity, and

comparatively isolated position of secondary schools in our educational

system, in many parts of the country, was incompatible with a highly pitched

graduation scheme. The aim of the commissioners to increase graduation was

entirely laudable. They wished to promote general culture, and arouse

academic ambition in the only way then possible. It was in the interest of

general culture that the degree of M.A. conferring membership of the General

Council and consequently a share in the business of the university, should

be held out, as a possible result of four years' diligence and average

ability, to a lad whose education in a rural school was of a comparatively

humble type. That it was successful is beyond question. For a considerable

time not more than half the students took part in the class examination. Not

long after, eighty per cent. did. There was a gradual raising of test and a

strict examination in all the subjects was rigidly enforced.

Between 1863 and the

commissioners' report in 1878 no new professorships or lectureships had been

founded in the University of Aberdeen. In St Andrews a professorship of the

Theory, History, and Practice of Education was instituted in 1876 on an

endowment provided for under the will of the Rev. Dr Andrew Bell of Egmore,

founder of the Madras system of education. In Glasgow two professorships,

one of clinical surgery and another of clinical medicine, were instituted by

the Senatus Academicus, with the approval of the University Court. An

endowment of £2500 was provided from private sources for each chair, and the

patronage was vested in the University Court. The incumbents of these chairs

were allowed to practise as a supplement to the endowment, which at 4 per

cent. would produce only £100. The respective rights, with regard to

graduation, of the two clinical professors on the one hand, and of their

medical colleagues on the other, especially the professors of practice of

medicine and systematic surgery, were subjects of keen controversy, for the

settlement of which the commissioners thought they had no authority, and

that it was more suitably left in the hands of the University Court.

Between 1863 and 1876 four

new professorships were founded in the University of Edinburgh by the

Senatus Academicus, that of engineering in 1868, that of geology and

mineralogy in 1871, that of commercial and political economy and mercantile

law in 1871, that of theory, history, and practice of education in 1876 [Reort

of Commissioners of 1876, pp. 51-3.].

The Senatus Academicus with

these additions was in 1876 the following.

In St Andrews, 2 Principals

and 13 Professors, in all 15.

In Glasgow, 1 Principal and 27 Professors, in all 28.

In Aberdeen, 1 Principal and 21 Professors, in all 22.

In Edinburgh, 1 Principal and 36 Professors, in all 37.

After discussing the general

propriety and expediency of the establishment of new chairs, the

commissioners urge caution in accepting offers of endowments for new

professorships. "Some of these may be highly beneficial, while others may be

of doubtful expediency ; and, to ensure that no chair shall be founded

without a full and unprejudiced consideration of the probable consequences

of its institution, and of the conditions under which its institution, if

resolved on, should be sanctioned, we think that some check on the power of

the universities to establish new chairs should be provided by legislation

[Report of Commissioners of 1876, p. 67]." They add however that the same

objections do not apply to lectureships, which are not necessarily of a

permanent nature, and may be discontinued if found to be unnecessary or

unsuccessful.

In the evidence given before

the commissioners in 1876 there was great variety of opinion about the

discontinuance of junior classes, in which the work done was more suitable

for school than university. The preponderance of evidence was against the

discontinuance, which was also the opinion of the commissioners themselves.

They accordingly advised their continuance, on the ground that, in many

parts of Scotland, the supply of such secondary education as would qualify

for entrance into a senior class is not to be had, and that university

education would be denied to many who might be able to turn it to good

account. They thought that any rule which would shut the gates of the

university against a student who failed to pass a certain examination would,

in the circumstances of Scotland, be injurious to the education of the

country ; that university attendance was unusually large in proportion to

the population; that educational conditions were very various, and not less

various the objects with which, and the ages at which, students came to the

university; that many of the backward students were beyond school age, and

could not be expected to return to school ; and, above all, that national

life and character had been for centuries most beneficially influenced by

the universities being accessible to all, even the poorest. With these views

the commissioners of 1889 agreed, adding, however, that while it would be

hard at present to discontinue junior classes in the interest of the

backward students, they thought it undesirable that they should be

permanent. They are now discontinued, but there are tutorial classes for

students preparing to pass the preliminary examination.

On the kindred question as to

enforcing a preliminary examination as a condition of entrance the

commissioners in 1876 took the same sound view. In this they were followed

by the commissioners of 1889 who held that the "first and indispensable

condition for the erection of a barrier at the gates of the university is

that candidates for admission should have sufficient means and opportunity

for preparing themselves for the university at school [Report of

Commissioners of 1889, p. x.]."

In 1892 in consequence of

representations made to the commissioners a preliminary examination was for

the first time instituted, in order (1) to maintain the distinction between

school and university education, and (2) at the same time avoid possible

injustice to candidates whose opportunities of getting advanced education

were unsatisfactory. The subjects of examination were English, Latin or

Greek, mathematics, and one of the following, French, German, Italian,

dynamics. As many candidates come from elementary schools which could

prepare students to pass in two, but not in the whole four subjects of the

preliminary examination, the commissioners ordained that "any student, who

had passed in Latin, Greek, or mathematics on the higher standard, may

attend a qualifying class in such subject or subjects without having passed

in the other subjects; but no candidate can present himself for examination

in any subject qualifying for graduation, till he has passed the whole

preliminary examination, nor can he be admitted to a degree in Arts, unless

he has attended qualifying classes for three years after completing the

preliminary examination [Ordinance 44, Section IV.]."

By this arrangement students

were permitted to attend the classes for which they had proved their

fitness. They could thereafter, either privately or in the summer vacation,

prepare to pass in the other subjects, instead of giving up the university

altogether. But for this modification of the original Ordinance students of

possibly great ability, though weak in classics and mathematics, would,

mainly owing to their distance from good schools, have been denied the

opportunity of reaching, as many such have done, high academic distinction.

A middle course between laxity and severity was chosen, a good deal being

left to judicious action on the part of the University Court, the Senatus,

and the examiners. Consideration was thus given to the unsatisfactory

condition of secondary education in schools, while at the same time the

standard of the preliminary examination was not lowered. It has been

contended with considerable cogency, that the gates of the university should

be open to all comers irrespective of attainments, provided, of course, that

teaching is not lowered to suit the ill-prepared, who must be content to

pick up whatever they can. Of the expediency of the policy of the open door,

Scotland's educational history can furnish many notable examples.

The standard for a pass in

the preliminary examination was prescribed by reference to the examination

for the three years' curriculum established in 1858, and to the leaving

certificate of the Scotch Education Department. To secure uniformity in all

the universities, a board of examiners was instituted consisting of

professors, lecturers on subjects qualifying for graduation, and additional

examiners appointed by the University Courts.

After passing this

examination, the curriculum extended over not less than three winter

sessions, or two winter and three summer sessions, a winter session

including not less than twenty, and a summer session not less than ten

teaching weeks. While the traditional number of seven subjects was

unchanged, it was felt that the course of study covered by them was wanting

in pliancy and adaptation to individual taste or bent of mind, and a great

variety of options was consequently introduced.

While the course was thus

widened and liberalised, care was taken that the humanistic culture

characteristic of an Arts degree was preserved, as will be seen below from

the specification of imperative and optional subjects. This widening of the

curriculum was thought to have a useful bearing on the relation of the

Faculty of Arts to the Faculty of Medicine, inasmuch as some of these

science subjects might be taken during the Arts course, and so shorten the

medical course by a year, and that its tendency would be in the direction of

enlarged liberal education for the medical student. In Aberdeen, where

natural history was compulsory, a medical student saved a year by taking

chemistry in his fourth year in Arts.

Candidates for the ordinary

M.A. degree might follow the curriculum, and graduate in the subjects

hitherto recognised for graduation according to the regulations laid down in

Ordinances 12, 14, 18 and 69 of the Act of 1858, or they might vary the

curriculum in the following way. They must attend full courses and pass in

seven subjects four of which must be (a) Latin or Greek; (b) English or a

Modern Language (French, German, Italian, Spanish) or History; (c) Logic and

Metaphysics, or Moral Philosophy; (d) Mathematics or Natural Philosophy. The

remaining three subjects might be chosen from the following departments,

subject to the condition that the group of seven subjects must include

either (a) both Latin and Greek, or (b) both Logic and Moral Philosophy, or

(c) any two of Mathematics, Natural Philosophy and Chemistry.

There were four departments.

1. Language and Literature.

Latin

Italian

Greek

Sanskrit

English

Hebrew

French

Arabic or Syriac

German

Celtic

2. Mental Philosophy.

Logic and Metaphysics.

Education (Theory, History and Art of).

Moral Philosophy.

Political Economy.

Philosophy of Law.

3. Science.

Mathematics.

Zoology.

Natural Philosophy.

Botany.

Astronomy.

Geology.

Chemistry.

4. History and Law.

History.

Constitutional Law and History.

Archaeology and Art (History of).

Roman Law.

Public Law.

A candidate for the M.A.

degree was not required to submit himself to examination in groups of

subjects. He might be examined in any subject, as soon as he had completed

attendance on the corresponding class. For the honours degree in Arts it

was, up to this time, necessary to pass in all the pass subjects, except in

the department in which the honours examination was taken. By the new

Ordinance exemption was allowed from some pass subjects in order that the

candidate might be free to devote his energies to the subjects in the

honours group in which he proposed to graduate.

The degree of M.A. might be

taken with honours in any of the following groups, provided honours classes

had been established in at least two subjects in that group:

(a) Classics.

(b) Mental Philosophy.

(c) Mathematics and Natural Philosophy.

(d) Semitic Languages.

(e) Indian Languages.

(f) English (Language, Literature, and

British History).

(g) Modern Languages and Literature.

(h) History.

(i) Economic Science (i.e.

Political Economy, with either (a) Moral Philosophy, or (b) History, as

Supplementary Honours subjects).

In each group there were three grades of

honours - first, second, and third class.

The candidate for honours

must take up at least five subjects, two of which must be selected from his

honours group. The five subjects must include one from each of the

departments of Language and Literature, Mental Philosophy, and Science.

The commissioners framed

Ordinances 31 and 45 instituting Faculties of Science (Report, p. xix).

These faculties vary in each university because the chairs in each are not

identical.

To enter in detail into the

matter of these two ordinances would far exceed our limits. It is perhaps

sufficient to say that "The Commissioners ordained that two degrees in

science may be conferred by each of the Universities of Scotland, viz.

Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.) and Doctor of Science (D.Sc.). These degrees may

be given in Pure Science and in Applied Science. To obtain the degree of

B.Sc. the ordinance prescribed the passing of a preliminary examination,

attendance on at least seven courses of instruction during not less than

three academical years and the passing of two science examinations."

In the University of

Edinburgh the prescribed subjects are (1906-7):

I. Preliminary Examination:

(1) English.

(2) One of the following - Latin, Greek, French or German.

(3) Mathematics.

(4) One of the following - Latin, Greek, French or German (if not already

taken); Italian, or such other language as the Senatus may approve,

Dynamics.

II. First Science

Examination:

(1) Mathematics or Biology

(i.e. Zoology and Botany).

(2) Natural Philosophy.

(3) Chemistry.

III. The Second Science

Examination is on a higher standard in any three or more of the following

subjects: Mathematics.

(1) Mathematics

(2) Natural Philosophy.

(3) Astronomy.

(4) Chemistry.

(5) Human Anatomy including Anthropology.

(6) Physiology including Histology and Physiological Chemistry.

(7) Geology including Mineralogy.

(8) Zoology including Comparative Anatomy.

(9) Botany including Vegetable Physiology.

Doctor of Science (D.Sc.).

Bachelors of Science of not

less than five years' standing may offer themselves for the degree of Doctor

of Science (D.Sc.) and must profess one of the branches of science

prescribed for the second science examination, in which they " will be

expected to show a thorough knowledge " as well as to present a thesis to be

approved by the Senatus.

In applied science the

degrees of B.Sc. and D.Sc. are conferred in the departments of engineering,

public health and agriculture.

Of the 169 ordinances issued

by the Commission Of 1889 41 are general and applicable to all the four

universities. It will be convenient to deal first with the most important of

these, and leave as far as possible those that have special reference to

each university to be taken up separately.

New Constitution of University

Courts.

The new constitution of the

University Court marks a change of very great importance. In 1858 the number

of members was in St Andrews and Aberdeen 6, in Glasgow 7, and in Edinburgh

8. In the new Courts the number in each was raised to 14, independently of

possible additions of 4 in the event of new colleges being affiliated. This

increased membership was brought about by introducing the Provosts of the

four university towns, and giving additional assessors to the Senatus and

General Council. It was only in Edinburgh that the Lord Provost and his

assessor were formerly members, a very proper recognition of the strictly

municipal origin of the university. By the introduction of the Provosts a

popular element of great value in keeping with the temper of the time was

contributed.

Increase in the membership

had a very distinct motive, and was accompanied by a large transference of

power and responsibility. Formerly, the Court was little more than a Court

of Appeal from the Senatus Academicus, which had the administration of

property and revenues, as well as discipline and education. In some of the

universities this power was thought excessive and

almost autocratic. By the new ordinance,

responsibility for discipline and education was left with the Senatus, but

the business management of property was vested in the University Court.

There were also certain decisions of the Senatus which it was competent for

the Court to supervise and review. This diminution of power had a partial

compensation for the Senatus in increased representation in the Court, and a

two-third share in the superintendence of libraries and museums.

Another new and valuable

element was the Students' Representative Council which had come

spontaneously into existence in 1884 and was now recognised by statute. It

is elected annually, and consists of representatives from the different

Faculties, and the recognised students' societies. Its functions are (1) To

represent the students in matters affecting their interests. (2) To afford a

recognised means of communication between the students and the university

authorities. (3) To promote social life and academic unity among the

students. Its constitution had to be approved by the University Court, and

it was entitled to petition the Senatus or the University Court about any

matter within their respective jurisdictions affecting the interests of the

students.

Among the most important of

the new features of the act was the provision for the extension of

universities by the affiliation of new colleges, such as the University

College of Dundee with the University of St Andrews.

Another feature was the

institution of the Universities' Committee of the Privy Council. This

committee was to consist of the Lord President of the Privy Council, the

Secretary for Scotland, and, if they are Privy Councillors, the Lord Justice

General, the Lord Justice Clerk, the Lord Advocate, the four Chancellors,

the four Lord Rectors of the universities, one member of the judicial

Committee of the Privy Council, and such other members of the Privy Council

as the Sovereign may appoint. This committee may be appealed to by the

Sovereign for advice, as to giving or withholding consent to any of the

Ordinances of the commissioners. For the purpose of this Ordinance any three

or more are sufficient, provided one is a member of the judicial Committee

of the Privy Council, and one a Senator of the College of Justice in

Scotland. In the entire field of university administration the Universities'

Committee was the supreme tribunal. Other changes of greater or less

importance were introduced. Power was given to the General Council to have

special meetings, in addition to the two statutory meetings, which formerly

were alone permitted. In universities where the Rector was elected by

`nations' the election was settled by the majority of votes and not, as

formerly, by the casting vote of the Chancellor, when there was an equality

of 'nations.' Where the election is not made by 'nations,' as in Edinburgh

and St Andrews, it is settled by the majority of votes.

It is a noteworthy

circumstance in connection with the Act of 1889, that while a period of two

years (with power to extend if necessary) was mentioned as probably to be

required for the work of the commissioners, it was not till after 251

meetings had been held that their task was completed in 1897, eight years

after their first meeting in 1889. The very extensive powers with which they

were invested sufficiently account for the greatly extended time. They had

before them the whole university system to examine and, if necessary, to

reconstruct. They were empowered to regulate the foundations,

mortifications, gifts and endowments held by any of the universities ; to

combine or divide bursaries and make rules for exercising the patronage of

them; to transfer to the University Court the patronage of all

professorships except those vested in the Curators of the University of

Edinburgh. This extensive charge however was accompanied by judicious and

necessary safeguards against hurried legislation. It is approximately

correct to say that draft ordinances, by whomsoever proposed, had, according

to definite arrangements as to times and seasons and order of procedure, to

run the gauntlet of criticism by the commissioners, the Senatus Academicus,

the General Council, the University Courts of the four universities, and

indeed by any person affected by such Ordinances, before they could be

submitted for approval by the Queen, who might further ask the advice of the

Universities' Committee, as the supreme tribunal in university proceedings.

The Ordinances having passed this ordeal, and having been laid before both

Houses of Parliament, received the royal assent and became law. The

publicity thus given to the Ordinances, and the keen scrutiny to which they

were subjected by all who, from different points of view, were interested in

them, might be expected to afford strong presumption of the general

soundness of the conclusions at which the commissioners arrived.

Subsequent experience however

has shown that this presumption was wrong. It was at any rate found after an

experience of ten or twelve years that though the Act of 1889 authorised

each University Court, after the expiry of the powers of the commissioners,

to make ordinances affecting its own university, all such Ordinances

required, before being submitted for royal approval, to be communicated to

the Courts of the other three universities, any one of which had the power

of making adverse representations to the Privy Council. The result was that

no Ordinance could be passed without serious difficulty and delay unless all

the universities were agreed. After much inter-academic negotiation, a

simple method has in 1908 been devised of remedying this unsatisfactory

state of affairs, and of securing 'autonomy' all round. An Ordinance is

obtained by one university making general regulations on some particular

subject affecting itself, and containing a clause authorising details to be

enacted and altered from time to time by that university alone, without any

power of scrutiny by the others or reference to the Privy Council. A

striking instance of this is furnished by the new Arts Ordinance for

Glasgow, which-to mention one point only-specifies 27 subjects from which a

curriculum may be made up, leaving it to the Senatus, with the approval of

the University Court, to make additions to or modifications in these, and to

enact from time to time regulations regarding the definition and grouping of

the subjects, their selection for the curriculum, their classification as

cognate, and the order in which they are to be studied, as also regarding

the standard of the degree examinations and the conditions of admission

thereto. Such regulations require to be communicated to the General Council,

but not to any outside body, either academic or governmental.

The course of medical study

was extended from four to five years. It was impossible, in view of such a

long course, to insist on medical students taking a full course in arts,

but, as a security for the possession of a liberal education, a preliminary

examination was instituted in the same subjects as for Arts students, French

or German being allowed as alternative for Greek. The extent and standard of

the examination were to be determined by the Joint Board of Examiners. It

was provided that there must be four professional examinations:- the first

in botany, zoology, physics, and chemistry; the second in anatomy,

physiology, and materia medica ; the third in pathology, medical

jurisprudence, and public health ; and the fourth in the various departments

of medicine, surgery, and midwifery.

It was not thought desirable

to establish an honours degree in medicine. In Arts a student can specialise

with advantage because he has already got a liberal education, though he is

possibly much stronger in classics than in mathematics, or in philosophy

than in either. But in medical study the commissioners remark: "every

candidate for this degree must have a competent knowledge of every branch,

and it is therefore impossible to acquire so exceptional a mastery of any

one as would justify a degree with honours [Report of Commissioners of 1889,

p. xvii.]." Notwithstanding some most sensible contentions for an honours

degree, it was thought " more important that the Universities should

encourage prolonged study in medical science by men of riper age, than that

they should recognise differences of degree in the attainments of

undergraduates [Ibid., p. xviii.]." Each university however confers the

degree of M.B. as a whole with honours, but without specification of honours

in separate subjects.

Some of the regulations

framed by the commissioners of 1858, in their endeavour to bring the

practice of the universities into harmony with the system introduced by the

Medical Act, were amended by the commissioners of 1889. They substituted the

degree of Bachelor of Surgery for that of Master of Surgery, and made the

latter a higher degree of the same rank as Doctor of Medicine. Both of these

higher degrees were obtainable only by those who, being already bachelors,

had spent an adequate time in additional study and practice of medicine or

surgery, had passed an examination in certain special departments and

submitted for approval of the Faculty of Medicine a thesis on one or other

of certain specified branches [Report of Commissioners of 1889, p. xvi.].

In 1858 it was decided to

give an academic character to degrees in law which had till that time been

purely honorary. With this in view the commissioners of that year ordained

that the degree of Bachelor of Law (LL.B.) should be conferred only on

graduates in arts, who must give three sessions to legal study in six

departments. The commissioners of 1889, while agreeing with this proposal,

thought it desirable to give the degree more elasticity and a wider scope,

so as to adapt it to the wants of other than practising lawyers,-to men

whose aim was a public or administrative career. The ordinance was

accordingly amended to the extent of giving options and adding to the number

of subjects as under:

1. General or Comparative

Jurisprudence.

2. The Law of Nations or Public International Law.

3. Civil Law.

4. The Law of Scotland or the Law of England.

5. Constitutional Law and History.

6. Conveyancing or Political Economy or Mercantile Law.

7. Two of the following: International Private Law, Political Economy,

Administrative Law, and Forensic Medicine.

In Edinburgh and Glasgow a

lower degree (B. L.), not confined to graduates in arts, had been

established, the requisites for which were passing the preliminary

examination in arts, three arts subjects, and four legal subjects-Civil Law,

Law of Scotland, Conveyancing and Forensic Medicine, two years of academic

study, one of which must have been spent in the university granting the

degree. St Andrews having no Faculty of Law could not give the degree. In

Aberdeen for some time only B. L. could be conferred, but in that

university, as also in Glasgow, an incomplete Faculty of Law was

supplemented by lecturers and now Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen can confer

both degrees [Ibid., p. xxii.].

Previous to 1889 classes for

women in Arts and Medicine, on a university standard, had been conducted in

Edinburgh and Glasgow outside the university. In St Andrews women were

examined and obtained the title of L.L.A., but there were no classes [L.L.A,

means Lady Literate in Arts.]. This remains unchanged. The title is obtained

by passing in seven subjects, of which at least one must be a language. All

honours passes count as two ordinary passes. The subjects of examination are

arranged in four departments: (1) language, (2) philosophy, (3) science,

(q.) education, Biblical history and literature. One subject out of each of

the first three departments must be chosen, the remaining subject or

subjects may be taken from any department. The examination may be taken at

any age, may spread over any length of time, and the subjects may be taken

in any order. In none of the universities had women been admitted to

graduation, but an Ordinance in 1892 admitted women to any degree on the

same terms as men. Where in arts, science, or medicine no provision was made

within the university for the education of women the teaching of any teacher

or institution in the university town might be recognised by the Court as

qualifying for graduation.

Graduation in Divinity.

The commissioners regret that

they can do nothing to remodel the Faculty of Divinity. In all the

universities the equipment is inadequate, the number of professors and

lecturers too few, and the salaries too small. They could not found new

chairs, as no portion of the parliamentary grant of £42,000 made in 1892

could be given to theological chairs beyond the sum, if any, which "had

been, within twelve months before the commencement of the act, appropriated

to such chairs out of public moneys." They dissented from the opinion of the

Edinburgh Faculty of Divinity, who held that the restriction was not

applicable to the parliamentary grant [Report of Commissioners of 1889, p.

xxiii.].

The admission to the degree

of Bachelor of Divinity (B.D.) of students other than members of the

Established Church was regarded by the commissioners of 1858 as a delicate

question, but as the universities favoured the proposal, no serious

objection was taken to it. Meanwhile in all the universities the practice

had been well established as by prescriptive right. All candidates were

examined, no vital principle was involved, and the commissioners of 1889

thought the "system was advantageous and ought to be confirmed." The

examination was accordingly opened to graduates of Scottish universities who

had gone through a due course of theological training whether in these

universities or' in any other theological school in Scotland or England.

It was suggested to the

commissioners that the degree of LL.D. might be made attainable by

examination, just as the higher degrees in science and medicine were

conferred, but as LL.D. had always been given simply as a mark of honour, it

was feared that confusion might arise from making it represent high legal

attainments also, which the degree of LL.B. sufficiently attested. This was

the conclusion to which the commissioners of 1875 also came. The degrees of

D.D. and LL.D. continue to be given honoris causa, the commissioners merely

remarking that they should be conferred with "due deliberation, and not in

deference to applications from without."

Additional Assistants.

There is no respect in which

the commissioners of 1889 have contributed so much to the improvement of the

university, as in the means they took to make provision for a steadily

increasing growth of students and new subjects of instruction, by adding to

the number of assistants and lecturers. Many of the classes were too large

to be managed by professors however accomplished and energetic. The number

of Latin students in 1889 in Glasgow was 453, and the number of anatomy

students in 1889 in Edinburgh was for winter 300 at lectures, and in

practical anatomy 534 for winter and 167 for summer. It was proposed to meet

this evil by extending to all the faculties the same recognition of

extra-mural teaching as had been given to the Faculty of Medicine. This

question was carefully considered by the commissioners of 1876, who thought

it would be injurious. With this opinion the commissioners of 1889 heartily

agreed.

The grounds were various.

One, but not the most important, was the diminution of the already too small

income of the universities. A much more important one was the almost

inevitable lowering of the instruction. The excellent results of extra-mural

teaching in medicine were no guide to the expediency of adopting the same

system in the Faculty of Arts. They pointed out that the aim of medical

teaching is the acquisition of definite and exact information, on which the

student is to be examined and pronounced qualified for a profession, and

that it is of comparatively little importance where or how his information

has been acquired, while the aim of a teacher in the Faculty of Arts is to

supply the broadening influence which forms the basis of a liberal

education, and that of the student is, or ought to be, primarily mental

culture, not ability to pass an examination [Report of Commissioners, p.

xxv.]. It is not insinuated that instruction in medical subjects may not be,

and in many well-known instances is, eminently scientific and stimulative,

nor that all students in the Faculty of Arts work under the inspiring motive

of mental culture, but it will be generally granted that the aim of each

class of students is different, and fairly represented by the account thus

given of them. If the extra-mural teachers are to live they must have large

classes, and large classes can be got only by the teachers earning a

reputation for success in enabling their pupils to pass the required

examination. It is inevitable that competition of this kind would take the

direction of examination success, to the detriment of the higher aim of

mental culture, which, from an academic point of view, would be a great

evil. To meet the case of subjects taking a wider range than formerly, or

the introduction of new subjects, or of classes unmanageably large, the

commissioners preferred to appoint assistants and lecturers, whose teaching

would be on the same lines as that of the professors, under the

superintendence and regulations of the University Court and Senatus, and, in

this way, to avoid the danger of cram, and the tendency to subordinate the

true principle of sound university education to examination aims. They

accordingly ordained that the University Court, after consultation with the

Senatus, should determine the number, duties, remuneration and tenure of

office of assistants and lecturers; that they should be recognised as

officers of the university but not members of the Senatus; that their

lectures should, as a rule, qualify for graduation, and that their

appointment, dismissal, and arrangements for teaching should all be under

the superintendence of the University Court and the Senatus. The

commissioners saw that, by the institution of this class of university

officers, encouragement would be given to post-graduate study and research

by students of promise, from whom there would be furnished for vacancies in

professorships a supply of candidates of successful experience, an

anticipation in many cases realised. It was the natural completion of

university promotion--bursaries to enable students of ability to follow a

course of study, scholarships and fellowships to reward excellence attained,

and professorships to crown the career.

Bursary Regulations.

The commissioners were

empowered to "frame regulations under which the patronage of existing

bursaries vested in private individuals or bodies corporate should be

exercised," but not to abolish the rights so vested. They had neither the

power nor the wish to throw them all open to competition. They knew the

unfavourable position of many candidates who, owing to the deficient

character of the schools in which they had been taught, were in this way

unfairly handicapped in competition with students who may have had better

preparation at school, but not necessarily greater ability. It is probable

that the donors intended their endowments for students of this class, and

their intention was entitled to respect. By Ordinance 57 the commissioners

made an excellent use of their limited power in this matter. Candidates for

bursaries not open to competition must pass the preliminary examination.

Candidates who failed to produce class certificates could be deprived of

their bursaries. Presentation bursaries could be thrown open to competition,

if the patrons did not fill up vacancies in due time. Bursaries of less than

£10 could be combined to make one of larger value, the restrictions being

removed wherever possible. Bursaries of doubtful usefulness were combined to

form scholarships and fellowships for the promotion of study and research, a

respect in which the universities were poorly provided. For a comparison of

the educational efficacy of competition versus presentation bursaries in

Aberdeen, see pp. 280-2.

Among the changes made by

Ordinance 57 there was one which was favourably received by all the

universities except by certain members of the University of Aberdeen. This

regulation was that "the examination subjects for open bursaries in arts for

the first year should be those prescribed for the preliminary examination in

arts, but under this condition, that in determining the marks to be assigned

in the competition, English, Latin, Greek and mathematics shall each have

assigned to them double the marks assigned to any other subject [Report of

Commissioners, p. xxix.]."

It is not clear why there

should have been in Aberdeen any objection to the doubling of the marks for

English, Latin, Greek, and mathematics, these being subjects in which

Aberdeen had the reputation of being strong, while it had no such reputation

for French or German. The Professor of Latin was opposed to the Ordinance,

but he objected not to the principle of differentiating values as between

classics and modern languages, but only to the method in which it was

applied [Ibid. pp. xxx and xxxi.]. In their report the commissioners thought

it necessary to make a reasoned statement in support of the Ordinance. Their

defence of the proposal is based on an assumption, the accuracy of which is

hotly disputed in quarters entitled to respect, viz. that "the time required

to bring a classical pupil up to the standard of a higher grade certificate

of the Scotch Education Department in Latin or Greek is twice or even thrice

the time required to prepare him for the higher certificate in French or

German." On this assumption, right or wrong, the commissioners maintain that

the proposal of double marks for the subjects named is fair and equitable;

and that, by placing French or German on the same level as Latin or Greek, a

powerful inducement would be given to candidates of small means, to whom a

bursary is indispensable, to give up Latin or Greek, and serious harm would

be done to classical education, as bursary examinations exert a powerful

influence on the curriculum of secondary schools. It is highly probable, in

view of the late successful efforts made by each university to secure

autonomy all round, and the framing of ordinances for the introduction of

'soft' options from which a curriculum may be constructed, that French and

German will at no distant date be put on the same footing as Latin and

Greek.

As women were now admitted to

graduation, it was necessary that bursaries should be provided for them. The

commissioners accordingly empowered the University Courts to establish for

competition either without restriction as to sex, or for women only, as many

bursaries as they might think necessary.

The commissioners of 1889

were empowered to establish bursary funds in all the universities. Under the

Act of 1858 a bursary fund was established in Aberdeen into which the

surplus income of some foundations, and the income of vacant bursaries were

paid. Out of it the cost of examination and the augmentation of bursaries

were met. Its accumulations now amounted to £10,500. The commissioners of

1889 thought that it was not advantageous to continue the Aberdeen bursary

fund; that it was better to capitalise the accumulated sum, and that "the

surplus income of any foundation should in future be added to the capital

fund of the foundation, and be applied to increasing the payments to the

beneficiaries [Report of Commissioners, p. xxxiii.]," the University Court

having power to increase or reduce the value of bursaries or scholarships as

they might think desirable.

Patronage and Pensions.

In dealing with the patronage

of professorships the commissioners had no difficulty with the provision in

section 14 for the transference to the University Court of the patronage

vested in private individuals or corporations other than the Curators of the

Edinburgh University. The only chairs to which it applied were those of

Humanity, Civil and Natural History, and Chemistry in St Andrews. The

patrons were the Duke of Portland, the Marquis of Ailsa, and the Earl of

Leven and Melville, who offered no objection. An ordinance was accordingly

issued and received the Queen's approval.

The power conveyed in

subsection 14 (e) was a matter of much greater difficulty, viz. "to prepare

a scheme by which a detailed and reasoned report on the qualifications of

candidates for chairs may be submitted to the patrons, including the Crown,

so as to assist them in the discharge of their patronage."

Success in framing a scheme,

accompanied by a detailed and reasoned report on a subject bristling with

difficulties from so many points of view, was not to be expected. The

commissioners, however, undaunted by the magnitude of the task, after very

careful consideration, issued a draft ordinance, to which objections were

made by all the universities, and by every corporation who had a share in

patronage, and the draft ordinance was withdrawn.

Additional funds were

required, and, in answer to an appeal to the Treasury, it was enacted that

an annual sum of £42,000, already referred to, was to be provided by

parliament for the purposes of the universities, which the commissioners

were to apportion in such shares as they might think just. This grant was

subject to two conditions: (1) That no university should receive less than

the average amount of public moneys which it had received during the five

years preceding the commencement of the Act of 1889, and that Glasgow should

receive £500 for the maintenance of the buildings, and Aberdeen £320 for the

purchase of books, in addition to the average amounts already mentioned. (2)

That no part of this increased grant should be appropriated to any

theological chairs except those of Hebrew or Oriental languages. It was also

enacted that, in future, pensions to principals and professors were to be

paid by the universities, and that the grant was a full discharge of all

claims on public moneys. A Treasury minute was however issued by the

Chancellor of the Exchequer, to the effect that he would recommend a

moderate increase in case of pecuniary difficulties in connection with

pensions and compensations. The commissioners were in the meantime, till the

ordinances were approved, empowered to make provisional payments out of the

surplus revenue from the grant, if they thought proper. On this

understanding, grants for the four years and a quarter from 1890 to 1893

were paid, to Glasgow nearly £35,000, to Aberdeen nearly £28,000, to

Edinburgh nearly £43,000, and to St Andrews for the eight years and a

quarter from 1890 to 1897 upwards of £46,000 [Report of Commissioners, p.

xxxiv.].

It turned out that pecuniary

difficulties did arise from the indefinite amount of possible claims for

pensions and compensations and, on the advice of eminent lawyers, the

commissioners expressed to the Government the opinion that further aid was

required "to enable the Act of Parliament to be carried into effect." The

result of this was that, under the Act of 1892, an additional grant of

£30,000 was made, which was a useful increase to the resources of the

universities, but the fluctuating charge for pensions was still a source of

embarrassment.

As a remedy for this, the

commissioners advised each university to establish a pension fund, by

setting aside annually, from the general revenues, a certain amount to meet

claims for possible pensions. This advice was taken.

The annual charge for St

Andrews was £750

The annual charge for Glasgow £4000

The annual charge for Aberdeen was £1500

The annual charge for Edinburgh was £5000

By Ordinance 32, section iv,

the annual emoluments of a Principal or Professor on retirement will be the

average of the preceding five years, provided that in calculating his

pension no account will be taken of the excess in any one year above £900,

which shall be held to be the maximum emoluments of a Principal or

Professor.

The maximum pension is £600

for professors of the following two classes, (a) professors appointed by the

Crown subsequently to 1882, (b) all professors by whomsoever appointed

subsequently to 1889. But professors may have a pension exceeding £600 if

(a) they were appointed by the Crown or any other body before 1882, or if

(b) they were appointed by any other body than the Crown between 1882 and

1889.

The patronage of chairs

varies considerably in the four universities, but a very large proportion of

it is in the hands of the Crown and of the University Courts.

In dealing with financial

arrangements the commissioners wished to leave to the universities, as far

as possible, a free hand, but the question of fees was too important to be

left untouched. It was necessary to consider how fees should be treated,

forming as they did part and, till now, a main part of the professors'

emoluments. The introduction of optional subjects for graduation in arts

made some change desirable. That the professor should have a direct interest

in fees led inevitably to unwholesome rivalry, and to a lowering of the

academic ideal, which ought not to have for its highest aim the preparation

of students for examination. Enlargement of class and consequent increase of

fees might, and probably would, tempt some professors to be content with a

lowered standard. But further, the consideration, among others, that the

higher and more advanced the subjects, the smaller would be both class and

fees, led the commissioners to ordain that class fees should be paid into

the University Court as the earnings of the university; that each professor

should receive a salary (called a normal salary) which might be diminished

proportionally, if the aggregate amount of fees in any year was unable to

meet the claims on the fee fund; but in order that the emoluments should not

fall below a certain amount, a minimum salary was fixed, which should be a

charge on the general revenue of the university [Report of Commissioners, p.

xxxviii.]. This arrangement involved a very serious reduction of the income

of a number of chairs, but even this, a very thorny subject, was settled to

the general satisfaction of those whose vested interests were very largely

interfered with.

New Chairs instituted.

Meanwhile fresh burdens were

laid on each University Court by the appointment of lecturers, the

institution of new degrees, and alterations in the course of study.

New chairs were instituted -

"in Glasgow, History and Pathology; in Edinburgh, History; in St Andrews,

Pathology, Material Medica, Medicine, Surgery, and Midwifery. By special

endowment there were instituted in St Andrews, the Berry Chair of English

Literature; in Glasgow, Political Economy; in Aberdeen, English Literature;

and in Edinburgh, Public Health [Report of Commissioners, p, xxxix.]." In

1901 the Chair of Ancient History was founded in Edinburgh, and in 1903 the

Chair of History and Archaeology was founded in Aberdeen.

Graduation in music is, as

yet, possible only in Edinburgh, a result of the Reid Bequest already

referred to. Two degrees may be conferred, Bachelor of Music (Mus. Bac.) and

Doctor of Music (Mus. Doc.), the latter being open only to Edinburgh

Bachelors of Music of not less than three years' standing.

The commissioners would have

liked to institute a separate faculty for every subject worthy of academic

study, and fitted to develop intelligence and refinement, but funds were not

available for the efficient maintenance of the faculties already existing.

The commissioners, like those of 1876, had not sufficient funds for the

establishment of new chairs, and they thought it undesirable to establish

chairs for which sufficient endowments were not provided. Lecturers on

specially important subjects might be appointed by the University Courts,

but permanent burdens which might prove too heavy should be avoided.

The moneys paid to the

universities on account of accumulations of revenue from the grants of 1889

and 1892 were to Glasgow £29,273, to Aberdeen £16,149, to Edinburgh £36,876.

The ordinances allowed the Courts of these three universities to make of

these moneys whatever use they might think fit. St Andrews, in the meantime,

could not be dealt with in the same way, owing to the litigation between it

and the University College of Dundee.

This litigation, which

commenced in 1890, and ended in 1897, being political or personal rather

than educational, seems hardly within the scope of our enquiry. To describe

in detail the legal difficulties and cross-purposes on both sides, which

punctuate the question before an agreement was come to, would be both

tedious and unprofitable.

Queen Margaret College,

Glasgow, had its origin in 1868 as the result of a movement for the higher

education of women by Mrs Campbell of Tulliehewan. For several years short

courses of lectures were delivered by professors of the university. The next

step was the formation in 1877 of the Glasgow association for the same

purpose, with H.R.H. the Princess Louise for its president, and Mrs Campbell

for its vice-president. Lectures on university subjects were, by permission

of the Senate, given by university professors in the university class-rooms,

the association meanwhile renting an office and reading-room. The next step

was taken in 1883 by the incorporation of the association as a college with

the name Queen Margaret, the earliest patroness of Scottish literature and

art. That it might not be merely a name, Mrs Elder, a lady of great

generosity and public spirit, presented the association with the building

now known as Queen Margaret College. The condition attached to this gift,

viz., that an endowment fund sufficient to provide for the effective

carrying on of the work should be raised, was in a short time amply

satisfied.

The contributions from

various sources amounted to nearly £25,000. Step by step, additions and

alterations, including laboratories for teaching in science and medicine,

were provided, and in 1890 such a curriculum in both Arts and Medicine, on

the level of university degrees, was arranged for, that in 1892 when women

were first admitted to graduation, the council of the college decided that

the purpose they had in view would be better served by making over their

work to the University of Glasgow. It was accordingly proposed, with the

concurrence of Mrs Elder, to offer a transfer of the buildings and grounds

of the Queen Margaret College to the university, on condition that they

should be employed for the maintenance of university classes exclusively for

women. The University Court accepted the offer, and Queen Margaret College

became part of the university, had its teachers appointed by the University

Court, and its students admitted as matriculated students. In 1907-8 the

number of matriculated women-students was 631.

For the promotion of

post-graduate study and the encouragement of research, an ordinance was

framed, under which the Senatus in each university might, with the approval

of the University Court, admit graduates of any university, or others whose

education fitted them to engage in some special study, to continue their

investigations, and possibly earn the title of Research Fellow on their

showing special distinction. The revenue of £20,000 furnished by the Earl of

Moray was placed in the hands of the University of Edinburgh for the payment

of the expenses of original research and the publishing of noteworthy

results.

Aberdeen has made a most

successful use of this ordinance and, under the able editorship of Mr P. J.

Anderson, has issued a series of publications for the supervision of which a

committee of the Senatus has been appointed, and the cooperation of the New

Spalding Club secured. No fewer than forty volumes have already appeared.

The subjects dealt with cover

a wide field, including, among others, Classical Archaeology, Scottish

History, Bibliography, Philosophy, Comparative Religion, Anatomy, Pathology,

Zoology and Chemistry. The object of the movement is to stimulate research

within the university by the teaching staff and others connected with the

university, and to unite by a bond of common interest and intellectual

fellowship alumni who, after leaving the university, too often lose sight of

each other. This has been followed by an interchange of volumes with

American, continental, colonial and the newer English universities. So far

Oxford and Cambridge have not organised an interchange.

The Carnegie Trust.

From yet another quarter

hearty encouragement in the same direction was received. In 1901 Mr Andrew

Carnegie, the well-known American millionaire, gave to Scotland-his native

country-the sum of ten million dollars (£2,000,000), the interest on

which-amounting to about £102,000 a year-was to be expended by a committee

of nine members to promote the following objects:

A. One-half of the net annual

income was to be applied to the improvement and expansion of the

universities of Scotland in the Faculties of Science and Medicine, and to

increasing the facilities for acquiring a knowledge of such subjects of a

technical and commercial education as can be included in a university

curriculum, by erecting buildings, providing apparatus, endowing

professorships, post-graduate lectureships, and research scholarships ; and

by other means approved by the committee.

B. The other half, or as much

of it as might be needed yearly, was to be devoted to the payment of the

ordinary class fees exigible by the universities or by extra-mural schools

providing an equivalent education, for students of Scottish birth or

extraction, subject to certain restrictions as to age, scholastic

qualifications, diligence and conduct.

It was provided also that any

surplus remaining in any year after the payment of fees under section B, was

to be applied to the purposes specified in section A, and any surplus

remaining after the requirements of both clauses were fulfilled was to be

devoted to the establishment of courses of lectures at convenient centres,

or to the benefit of students at evening classes, or to such other objects

as the committee might think proper.

Under section A the committee

distributed no less than £178,000 up to the 31st Dec. 1906, at which date

they carried forward a balance of £125,000. The aid thus given greatly

improved the efficiency of the universities and other institutions, whilst

the stimulus given to higher study and original investigation by the

research scholarships has proved of the utmost value. In session 1906-7 the

Trust awarded 20 fellowships, 26 scholarships, and gave 57 grants for

promotion of postgraduate study in the four Scottish universities.

In the four universities

considerable disparity is shown in the number of students for whom fees have

been paid. In the six academic years up to and including session 1906-7, 69

per cent. of the students matriculating at Aberdeen became beneficiaries of

the Trust. St Andrews came next with 67 per cent. whilst Glasgow and

Edinburgh had only 49 and 38 per cent. respectively. The abnormally low

percentage at Edinburgh may be accounted for partly by the large number of

other-than-Scottish students matriculated there, and by the number of law

students who attend classes, but are excluded from the benefits of the Trust

through not having passed the preliminary examination.

It is impossible to speak too

highly of the beneficent operation of section A, but appreciation of section

B has not been so hearty and unanimous. Doubts have been pretty freely

expressed as to the expediency of practically making a pass in the

preliminary examination the only condition of obtaining a free university

education. It is beyond question that many, of whose ability to pay their

own fees there could be no doubt, have taken advantage of this, and the

result has been, as some think, a lowering of self-respect and a slackening

of effort in university pursuits. It has not increased the number of

students, which was perhaps not desirable. Administration was difficult even

for the eminent men whose selection as trustees was heartily approved. There

were many points to be considered requiring a more intimate acquaintance

with the character of Scottish education than the trustees as a body

possessed. Hence there has been a want of consistency. The first set of

rules were found to be unworkable, and had to be exchanged for another set,

the former by their wide scope suggesting that the Trust was an educational

endowment, the latter, by refusing (among other claims) payment of fees for

optional advanced classes, that it was a charity, securing for the

comparatively poor student a minimum of university training. It is however

only fair to say that the trustees were dealing tentatively with a movement

the issues of which it was difficult to foresee ; and that consistency was

limited by the amount of funds available. Students who have availed

themselves of the offer of free fees are expected to repay, when they can,

what they have obtained by exemption from the payment of fees. It is much

too soon to expect a large return from this source.

Higher Degrees.

An important ordinance was

framed for regulating the higher degrees of Doctor of Science (D.Sc.),

Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) and Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.), which, under

certain conditions, might be conferred after the expiry of five years from

the date of graduation in arts. All candidates for these higher degrees must

either have taken honours in the subjects of the degree for which they are

candidates, or have passed an examination of value equivalent to an honours

examination. Each candidate must submit a thesis or memoir cognate to the

degree aimed at, accompanied by a declaration that it was composed by

himself. To secure that the work for which these degrees may be conferred is

an original contribution, it is provided that an expert in the subject of

the thesis must be associated with the university examiner, and that the

thesis must be published.

The most important of the

general ordinances have now been dealt with. The varying conditions of

individual universities in respect of management, equipment, revenues,

faculties, &c. made separate ordinances requisite. To enter into these in

minute detail is not possible, nor for our purpose necessary. It has been in

some cases difficult to keep the general and special entirely separate.

Medical Study in St Andrews

and Dundee.

Lectureships on fifteen

university subjects have been instituted in St Andrews within the last

fifteen years, only a few of which have been endowed. Between St Andrews and

Dundee there is now a complete medical faculty. In fact there is a complete

faculty in Dundee alone, as all the St Andrews' chairs have been duplicated

there. A medical student may begin and end his course in Dundee. If he

begins in St Andrews he must finish in Dundee, because St Andrews has not

sufficient hospital facilities.

In St Andrews special

ordinances were required in connection with graduation in medicine; the

abolition of the Professorship of Medicine and the substitution of a Chair

of Botany in its place; the abolition of the Professorships of English, and

of Classics, and Ancient History, in University College, Dundee, and the

substitution of lectureships in these subjects qualifying for graduation if

required by the council of the college; St Andrews' share in the

parliamentary grant; the composition of the faculties; regulations for

bursaries and prizes; the foundation of the Berry Chair of English

Literature [The Berry Bequest was a sum of £100,000 bequeathed to the

university in 1889 by Mr David Berry of Coolangatta, New South Wales, whose

brother Dr Alexander Berry had been a student at the university. It has been

used for the foundation of the Chair of English Literature, for the better

endowment of other chairs, for the establishment of scholarships and other

purposes.], the institution of boards of studies in medicine, and the

appointment of a lecturer on forensic medicine and public health in

University College, Dundee. For all these separate ordinances were framed.

The commissioners of 1889

wished to establish uniformity of system in medical graduation in all the

universities, but St Andrews presented considerable difficulties. Reference

is made to a special report in 1861 by the commissioners of 1858, in which

it was stated that "at that date St Andrews, with no medical students,

conferred a greater number of medical degrees than any other University in

the United Kingdom. Of the candidates for these degrees, 68 per cent. came

from London schools, and 77 per cent. from these and the provincial schools

of England together [Report of Commissioners, p. Iv.]." This had a very

suspicious look, suggesting great possibilities of abuse, and some

restriction was obviously necessary. The commissioners of 1858 accordingly

ordained that degrees of Bachelor of Medicine and Master in Surgery should

be conferred only after a specified course of study, and that two out of the

four years of study should have been spent in a university, and that, in

exceptional cases, the degree of M.D. might be conferred, but not to a

greater extent than ten cases in any one year. Complaint was made that St

Andrews was being deprived of its ancient privilege of conferring degrees

without residence. The commissioners of 1876 took the same view as to the

necessity of restriction as the commissioners of 1858 and recommended that

it should not be removed.

The commissioners of 1889

agreed with this for the very satisfactory reason, that to confer degrees on

licentiates, who might not have obtained any part of their education in a

university, was not only a violation of academic usage, and a probable

injury to other universities, but a certain lowering of the reputation of

Scottish medical degrees. The commissioners accordingly continued the

restriction and even increased the limitation by ordaining that "the power

of St Andrews to confer the degrees of Bachelor of Medicine and Master in

Surgery on the students of other universities should be discontinued [Report

of Commissioners, p. lvi.]." They also refused in the meantime to establish

medical professorships in St Andrews [Ibid. p. ivii.], but they could not

prevent the University Court from instituting lectureships by which the

subjects in question could be taught. The objections to these ordinances

were discussed by counsel before the Universities' Committee, and the

ordinances were approved by the Queen in council.

With reference to extra-mural

teaching in science the commissioners ordained that it was permissible on

the same grounds as extra-mural teaching in medicine. The ordinance

prescribes that, out of seven courses in science, three might be taken

outside the university conferring the degree.

Special ordinances were

needed for separate universities. Thus the following degrees in applied

science were granted.

In Glasgow.

Bachelor and Doctor of Science

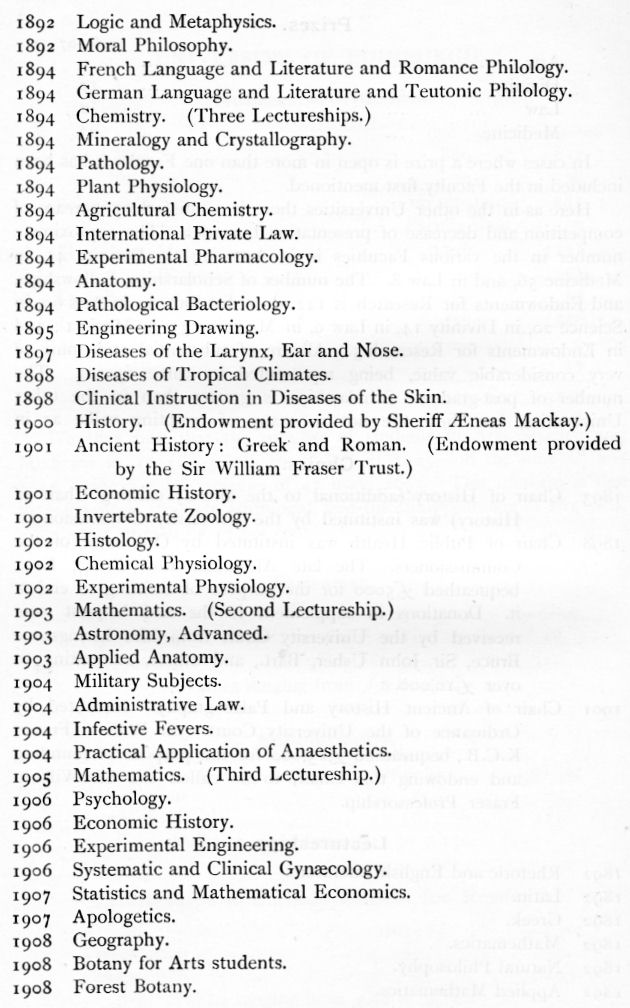

in Engineering.