|

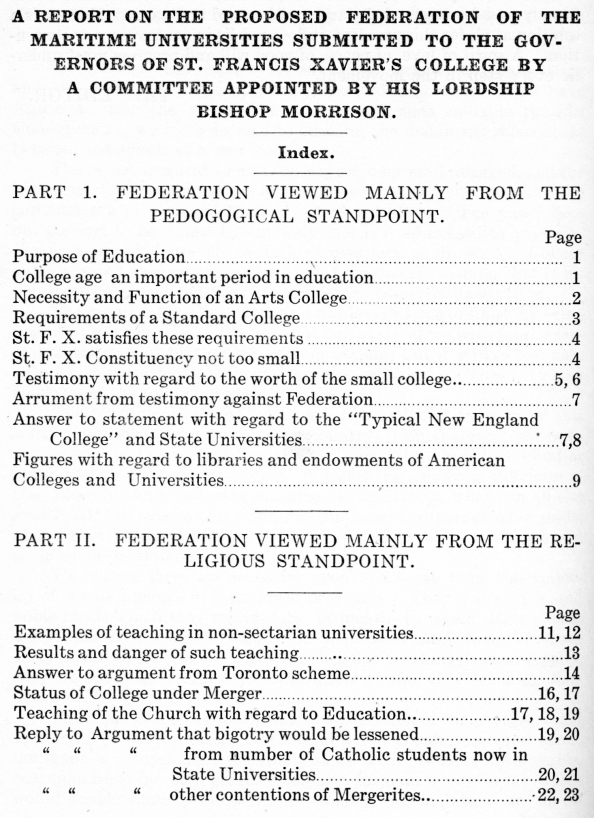

THE COLLEGE MERGER OF THE

MARITIMES.

We publish the report set

out below because it is interesting and deals with a public question of

exalted importance. We have reason to feel the folly of not preserving

such valuable records. Consequently, we have decided to embalm the

document referred to between the covers of a new book.

The report was sent to us a

few days ago by mail unasked, and the kind sender is to us nameless and

unknown. Even the names of the committee who prepared the report are not

given. The paper does not purport to be signed by anybody; nor is it

addressed to anybody. We understand, however, that the Governors of St. F.

X. College have adopted this report, and we must, therefore, assume that

it represents the considered views of that much respected institution.

The report is lengthy. It

would not loss in force or finish by being just a bit more concise. We may

not be able to agree with all the several statements of that lengthy

memorandum; but it strikes one note with which we do agree without

hesitation or reserve. That note may be given in the following terms and

manner:

The teaching of Christ is

the greatest and best force in all this world. No school in any christian

country, from the humblest common school to the highest imaginable

University, should be blind or indifferent to that supreme force. Without

the steadying influence of this inerrant and enduring teaching of the

Master, what can all else avail? Ask the wrecks and ruins, the punished

and perpetuated pride, of the most powerful ancient empires, to which

alas! we must add some modern empires, as well!

We believe there are no

better people on earth than the majority of our own people in these lower

provinces. They have high and noble ideals which they would fain bequeath

to their descendants. They want a University worthy of themselves and

their children. They are all as one in their desire for christian

teaching; but, unhappily, they are not as one in their interpretation of

the very teaching they look for.

Then, the problem

confronting the federation of the colleges would appear to be simply this;

Can the different creeds meet and agree, not upon a compromise, for

compromise with truth is unthinkable, but upon some binding, practicable

basis, formula or concordat which would enable them to build, equip,

conduct and maintain, an up-to-date University which would be virtually

undenominational, but frankly and fearlessly christian in wish, word and

work. If there is a solution at all for this problem it does not lie in

controversy or contention. A spirit of love, of peace, of good will and

progress, must underlie every step in the movement.

THE EDITOR.

The purpose of education is

to help men to live well. This is the reason for the existence of our

common schools, high schools, colleges and universities. But men cannot

live well no matter how highly trained they are in the secular sense

unless their activities are guided by the principles of religion. Religion

is not something for Sunday alone. It should guide man in all his

activities. Now Man's activities depend to a great extent upon his ideas.

If, therefore, his activities are to be right, his ideas must be right,

they must conform to christian truths. On this account education in the

public schools, high schools and universities should not leave christian

principles out of account but should be guided by them. Probably

universities need the guidance of religion most of all. And why ? Because

their influence on life is so important and because they give us new ways

of doing things, they aim to develop hidden powers. These new ways of

doing things must conform to the christian law and for that reason they

should be taught under christian auspices. For example, many suggestions

as to how to live come from the biological departments of our

universities. Some of these suggestions are productive of much evil

because they are against christian truth. Many suggestions as to how to

live from the economic and social departments of our universities; many of

these do harm because they are pagan. The late Theodore Roosevelt is

quoted as having said that there is not a disrupting and dangerous

movement in the United States but can be traced to Harvard University. Our

mode of living, whether it be according to the ways of our fathers, or

whether it be new, depends on our education. Our educational system from

the universities down, moulds our activities, and for that reason it

should be christian from top to bottom.

The troubles of the world today are due to the divorce of religion and

education, especially in the colleges and universities. Their pagan

teachings have filtered down to the man in the street. The remedy lies not

in less religion in college and university teaching, but more.

In the life of the

individual the period of college age is considered most important. "This

period of adolescence'' says Dr. McCrimmon Chancellor of McMaster

University, "is now recognized as a most critical one in the organization

of the factors of life in the unifying of the outlook upon life, in the

choice of a life-work, in the adoption of life's ideas." Stanley Hall,

Clark University, one of America's greatest psychologists says: "The young

pubescent achieving his growth in the realms of fundamental qualities,

dimensions, functions comes up to adult size at 18 relatively limp and

unfit like an insect which has accomplished its last moult and therefore

far more in need of protection, physical care, moral and intellectual

guidance." "Now come epoch-marking physical changes, sex modifications of

far-reaching importance," says Chancellor McCrimmon of McMaster

University, "mental correlatives of revolutionary character, the storm and

stress of new emotions, the conflict of intellectual standards the varying

emfases of resolutions, the criticism of earlier religious experiences,

the age when by far the greater number of conversions take place.''

Amid all this

adolscence,vacillation and uncertainty, these varying emfases, this

struggle after foundations and ideals, that are some of the factors which

appear at once capable of steadying this adolescent life and guiding it

towards christian leadership? It is not so much the mingling with other

adolescents who, in the words of Stanley Hall, have accomplished their

last moult, helpful as that may be, but contact with strong consecrated

experienced personalities, with an atmosphere and conditions which mature

aright, and with a continuity in the influence of such personalities and

conditions. Can we do anything to guarantee the christian character of the

teacher, the religious atmosphere of the school, the conditions of the

daily and hourly round of consecutive duties? It is only the christian

college that is free to do this, the college that is avowedly christian

that insists upon evangelical church membership for its teachers, that

considers its work a mission of Christ. Notwithstanding all that christian

teachers may do wherever they may be working, no state system can

constitutionally provide such conditions.....The state schools are worthy

of all praise as they direct students to the truth but after all any truth

is unrelated truth, is truth without its meaning for life until it is

centred in Christ the Son of God, the God of truth. Each one of the

factors; personality, atmosphere, continuity of influence, is of vital

importance To furnish such factors is a most difficult task and demands

the fullest possible control."

The work of education has

been compared to the work of a sculptor. Let us imagine the case where

several sculptors work on the same statue. Let us further suppose that one

sculptor has one idea of what the work should look like when completed and

another has a different idea. In such a case the statue will be anything

but a success. The work would be ridiculous. It is just as ridiculous to

have several agencies, who disagree on fundamentals, educating our youths.

Liberal training to be successful must be a co-operative enterprise. The

teachers must have definite ideas as to the aim of a college course and as

to the best methods of attaining that end. Failure can only result where

one part of the Faculty has one set of ideas on this matter and another

part of the Faculty another set of views. One part may even (and must be

in the case of the merger) be tearing down what the other part is building

up.

The importance of

co-operation in teaching is explained by a number of writers recently in

"School & Society."

A writer in the Dublin

Review, Dec. 1851, p. 585, says on this point: "Once more and fourthly, as

a condition of success, we must name a perfect unity of thought and

purpose in the teaching body. Mixed education makes this impossible. Thus

the Bishop of Liege remarks in his valuable letters. 'What is your

secret,' an intelligent man one day asked me, 'for making your

establishment flourish?' 'It is, I replied to him, 'the homogeneousness of

the professional body. And this may easily be conceived. When all the

members of this body have but one thought and one action to inspire into

the minds of youths with the love of knowledge, that of virtue and

religion, may one not expect, with some confidence, happy results? But

what are we to expect where there does not exist this unity of views and

actions?"

Divided control,........one

set of teachers proclaiming one thing and another proclaiming the opposite

would probably lead the average plastic college student into scepticism.

Necessity and Function of

an Arts College.

The work of education is

divided between the common schools, high schools, colleges and

universities. Here we are concerned with the work of the colleges. In some

quarters there have been tendencies to destroy the colleges, in various

ways and for various reasons, some of them not altogether unselfish. Some

would split their work up between the high schools and the universities,

but on the whole the college of liberal arts is considered necessary, and

its existence is assured. Donald J. Cowling, Ph. D., LL.D., President of

Carleton College, said on the occasion of the inauguration of President

Burton of the University of Michigan, 1920, that "The aim of a college is

just as definite as that of any professional school." "That aim," he said,

"is to develop the student with respect to all his capacities into a

mature symmetrical and well-balanced person, in full possession of all his

powers, physical, social, mental, spiritual and with an intelligent

understanding of the past and a sympathetic insight into the needs and

problems of the present." The purpose of the college is to develop

leaders,........leaders who will harmonize the conflicting aims of various

classes of society. The professional schools and graduate schools of the

universities alone will not and do not produce these leaders. Their

training is too narrowing to enable their students to see things in their

proper perspective. This vision comes from the liberal arts training. On

this point, President Rush Rhees of the University of Rochester, says: "I

believe that the American College contributes to preparation for

professional studies an influence for intellectual maturity which no other

agency has to offer. By intellectual maturity I do not mean simply

developed intellectual power, for professional studies as at present

conducted have no superior in that respect. I mean by intellectual

maturity a well-balanced judgment, a sense of proportion in the estimate

of truth and ability to see facts in larger and more remote as well as in

nearer and obvious relations."........But college education offers the

most promising means for such intellectual emancipation.

But how can the college

give "this sense of proportion etc." if it leaves revealed truth out of

account in some of the college courses. The college then has a function to

perform, viz., the creation of broad-minded leaders, but it cannot do this

unless it is christian through and through.

One of the functions of

leaders is to show men how to deal with one another in their social

relations. On them depends the development of a public opinion that will

lessen disorder, unrest, economic strife and the wastes of war. On them

depends the solution of the social question which according to Pope Leo

XIII "is first of all moral and religious." Our leaders cannot do their

work without the guidance of christian truth. Hence a college education

that leaves Christianity out of consideration, is defecient and cannot

produce leaders competent to direct men in their social relations. This is

abundantly shown by the quality of the eugenic, psychological and

sociological literature that is pouring out of our non-sectarian

universities.

Elements of a Standard

College.

To do this work of creating

leaders efficiently a college must meet certain standard requirements; it

must have a certain amount of equipment and its teachers must possess

certain qualifications, but above all it must be thoroughly Christain.

It is claimed that Saint

Francis Xavier's college does not and cannot meet these requirements, and

it would meet them and do better work if it entered the Merger.

What are the requirements

for a standard college? Remember we are concerned with the requirements

for a standard college and not with those for a large university with

professional schools, etc. Confusion on this point would seem to be at the

root of a great deal of the agitation in favor of the Merger. It is not

claimed that at present we could run a university with its many faculties,

etc., but it is claimed on the best of authority that we can run an

efficient college. What is that authority?

A committee of the

Association of American colleges investigated for a number of years the

subject of the requirements for a standard college and submitted their

final report to the Association in 1917. They distinguish between an

Average College, a Minimum College and the Efficient College.

The Minimum College should

have 100 students, a faculty of ten including the President and Librarian,

should have an income from all sources of $32,000, should have equipment

worth $350,000, and endowment worth $432,000.

Dean Cole, President

Oberlin College, in explaining the term Minimum College said:

"By this term I understand

that we mean not to describe the smallest institution we think should be

allowed to bear the name of College, but rather an institution having such

admission, requirements curriculum, standards for graduation, teaching

staff, administrative organization, endowment and physical equipment as

render it capable of doing acceptable college work in every respect for an

arbitrarily fixed number of students."

The Average College will

have one hundred and sixty-five students distributed as shown; it will

have a faculty of sixteen, one of whom will be the president, another the

librarian, the others being instructors. It will have an income of

thirty-six thousand two hundred and fourteen dollars."............."The

total invested in the plant will be $236,877 and the total endowment will

be $265,170. To capitalize donations and deficit would require $189,840,

making a total endowment of $455,010."

The committee also drew up

standards for what they called the efficient College. There was some

objection to the use of the term "efficient." It was admitted that

colleges that are not as large as the Efficient College are doing and can

do just as good work as the Efficient College.

In the words of the Report:

"There is no implication that colleges which fail to meet the tests of

efficiency as set forth in the discussion are not good colleges." And in

the words of the Committee on the distribution of colleges; "These

statements should in no case be construed as implying that smaller

colleges adequately endowed to provide a full staff and generous equipment

for a smaller enrolment are not desirable. Wherever in the country such

small colleges are maintained, they can do superb work."

The Report says: "There is

a wide difference of opinion with regard to the desirable limit of numbers

in a student body. Probably none would contend for a number larger than a

thousand. Many would be willing to say that five hundred is the best

number. No doubt, most educators will agree that certain conditions of

unity homogeneity and intimacy should characterize a college group and

that these conditions indicate a certain limit as to numbers. Certain

personal relations between teachers and students should exist and these

also indicate some limitations as to numbers. Chiefly, however, for the

practical purpose of getting a starting point from which to develop the

efficient college, we will assume a student body of five hundred. It

should have a faculty of forty-six consisting of twenty-two professors,

sixteen assistants and eight instructors. It should have a library of

25,000 volumes. Its total income should be $166,750. Such an institution

is characterized as "Efficient", because "If the number of students should

be small the per capita cost would be high. As the numbers increased the

per capita cost diminished until at an enrolment of 400 to 500 it becomes

merely stationary and showed little or no decrease for enrolment increase

beyond this number."

A comparison of these

standards with conditions at St. Francis Xavier shows that our college has

more than is required by the standard college of our size. We have

practically the plant required for an "Efficient College." We have an

endowment practically secured of over $800,000. The Association requires

for an Efficient College, a library of 25,000 volumes". We have probably

15,000 volumes. True, many of these are not what would be called college

books, still they are valuable assets. But surely it should not be a

difficult proposition to increase our number of college books to 25,000.

It has been contended that

our constituency is too small for an Efficient College. This is not the

judgment of the best available authority on the question. A Committee of

the Association of American Colleges were at work on this question and

brought in a report in May, 1921. It may be remarked that Dr. Clyde Furst

of the Carnegie Foundation was one of its Advisory Members. They found

that there was in the United States an average of one college student per

212 population. In some places the average is much greater; 1 to 145, 1 to

147. As the high schools multiply and improve there may be 1 student in

100 population.

Let us take the average in

the whole United States, 1 in 212. The Catholic population of this diocese

is estimated at 85,000. According then to the statistics of college

attendance in the United States, we should even now have over 400 college

students in our constituency. In time, no doubt, our people will be able

to send their boys and girls to college in the same numbers that they are

sent elsewhere. And besides it is not unreasonable to expect that Cape

Breton and Eastern Nova Scotia will share some of the increase in

population and prosperity that is supposed to come to Canada in this

century. However that may be, we have even now according to the estimates

of the committee of the Association of American Colleges a constitutency

large enough for the Efficient College.

Can we hope to become an

Efficient College? The progress made during the past ten years would seem

to warrant the conclusion that we can. During the past twelve years the

college course has been lengthened by two years, the endowment has been

increased by $785,000 and the equipment by $351,000. (The Science Building

$60,000; the chapel $25,000; the library $15,000; the gymnasium $20,000;

the Rink $30,000; the Heating Plant $113,000; Mount Cameron Farm $40,000

and Mickler Hall $48,000 have been added to the Plant within the last

fourteen years.) Six of these years have been very hard on the colleges.

Surely then the history of the past twelve years warrants us in believing

that when normal times return our college may hope to attain the most

exacting requirement for a standard college. But perhaps we could do

better work if we were part of a large University. Let us examine this

argument from size.

Argument from Size.

The efficiency of a college

depends but slightly upon its size. It depends upon the relationship

between equipment, etc., and the number of students. Prof. Frank Aydelotte

of Swarthmore College writes in the Nov. 5, 1921 No. of "School & Society"

that provided the small colleges limit the number of their students and

the subjects they teach "the size of an institution need have no effect on

the quality of its work." Any efficiency that comes from bigness is had

when the number of students reaches 500. The small college of less than

200 students can do excellent work, and in the judgment of competent

authority is in many cases doing better work than the large institutions.

At a meeting of the Association of American colleges held in 1917, Dr.

Crawford made the statement that Haverford was the best college in the

State of Pennsylvania and it never had more than 176 students. From a

discussion of the relationship between the size of a college and its

efficiency, between Dr. Crawford and Dr. Cole, at this meeting as reported

in the Bulletin of the Association, the following is taken:

Dr. Crawford: Then there is

no indication whatever in your remarks that because the college grows

larger it necessarily grows better.

Dean Cole: No, that doesn't

follow. It ought to, I think, but as a matter of fact it doesn't.

Question: I think I have

read somewhere in statistics from our Government that a larger percentage

of graduates of colleges with less than 500 students had become

distinguished than from colleges of more than 500 students. Is this True?

Dean Cole: I do not know.

Question: I think that is

so. If so, is not your assumption that the larger a college is, other

things being equal, the more efficient it will be is't that assumption

wrong?

Dean Cole: That question is

quite possibly wrong, under present conditions, but it is not my

assumption.

Thorstein Veblen, by many

considered the most brilliant mind in America, and for many years the

University of Chicago's most distinguished professor discusses in his book

"The Higher Learning in America," the attempt to join college and

university together.

The value of Veblen's

authority may be judged from the following criticisms of his works: "The

Publishers' Weekly," Sept. 7, 1918, says: "The appearance of a book by

Thorstein Veblen is always one of the literary events of the year in which

it occurs. Veblen holds, in political theory, the position that Emerson

ascribed to Plato in philosophy. Very few of us read Plato, but we all owe

our education to him, for he teaches our teachers. Veblen's mind is more

like the X-ray than any other thing. When once you have looked with him

into the very centre of social and political customs, nothing can erase

the picture from your mind. Those who like to keep up to date in reading

usually do not read Veblen. He is about fifteen years ahead of date. But,

considering the present rush of events, it might be well to read him, so

as to be prepared if the present has a telescope wreck with the future in

about fifteen minutes. "Higher Learning in America." (Huebsch.)

The "London Nation" calls

Veblen, "the most original modern thinker. His contributions to Sociology

and Economics have had a profound influence, and those who seek

understanding of the origin, development and direction of our own

industrial society, must study Veblen's works." The "London Nation" is,

unquestionably, the formost literary review of our day and generation, and

"The Publishers' Weekly" is the most influential and authoritative organ

of the publishing and book-selling trade in America.

The "American Economic

Review" describes Veblen as the "pre-eminent thinker in the field of

critical thought relating to modern economic study."

"The American University,

Veblen says, has come into bearing, and the college has become an

intermediate rather than a terminal link in the conventional scheme of

education. Under the names of "undergraduate and graduate", the college

and the university are still commonly coupled together as subdivisions of

a complex whole; but this holding together of the two disparate schools,

is at the best a freak of aimless survival. At the worst, and more

commonly it is the result of a gross ambition for magnitude on the part of

the joint directorate.............The attempt to hold the college and

university together in bonds of ostensible solidarity is by no means an

advisedly concerted adjustment to the needs of scholarship as they run

today. By ill-advised or perhaps unadvised imitation, the younger

universities have blundered into encumbering themselves with an

undergraduate department to stimulate this presumptively honorable!

pedigree, to the detriment of both the university and the college so bound

up with it."

"It appears then that the

intrusion of business principles (by this he means trustification or the

grouping of colleges etc., into large units) in the universities goes to

weaken and retard the pursuit of learning, and, therefore, to defeat the

ends for which a university is maintained. This result follows, primarily,

from the substitution of impersonal mechanical relations, standards and

tests, in the place of personal conference, guidance and association

between teachers and students; as also from the imposition of a

mechanically standardized routine upon the members of the staff, whereby

any disinterested preoccupation with scholarly or scientific inquiry is

thrown into the background and falls into abeyance. Few if any who are

competent to speak in these premises will question that such has been the

outcome."

In another place he writes:

"It is coming to be plain to university men who have to do with the

advanced instruction that, for the advanced work in science and

scholarship, the training given by a college of moderate size commonly

affords a better preparation than is had in the very large undergraduate

schools of the great universities. This holds true, in a general way

in spite of the fact that the smaller schools are handicapped by an

inadequate equipment, are working against the side-draft of a religious

bias, with a corps of under-paid and over-worked teachers in great part

selected on denominational grounds, and are under-rated by all concerned.

The proposition, however, taken in a general way and allowing for

exceptions is too manifestly true to admit of much question, particularly

in respect of preparation for sciences proper as contrasted with the

professions." Veblen: Higher Education in America, p. 126.

Prof. Veblen proposes that

these universities be broken up into independent units, and says: "Indeed

there might even be ground to hope that, on the dissolution of the trust,

the underlying academic units would return to that ancient footing of a

small-scale parcelment and personal communion between teacher and student

that once made the American college with all its handicap of poverty,

chauvinism and denominational bias, one of the most effective agencies of

scholarship in Christendom."

Any amount of testimony to

the same effect could' be brought forth. Two more will suffice.

Prof. Vernon L. Kellogg, M.

S. Secretary of the National Research Council of the United States said at

an educational conference held at the University of Michigan in Oct. 1920:

"Another familiar fact of general knowledge is that a major part of

university research in this country comes from a comparatively small

number of larger richer better-equipped, more brilliantly-staffed

institutions. But it is less familiar that the great majority of the

graduate or research students of these larger institutions come to them,

not from their own annual output of bachelors but from other smaller

colleges and universities. The dean of the graduate school of one of these

largest universities, particularly famous for its annual output of

graduate degree men, reports that ninety per cent of its graduate

students come from other smaller institutions." (Educational Problems

in College and University p. 81.)

And in the Report of the

British Educational Mission to the United States, 1919, we read:

"Colleges have the same

curricula and standards (as the university) ; and many of them possess the

advantage that their numbers being limited, the students may expect more

personal attention...........

We were frequently assured

that the best intellectual material of the graduate departments of the

universities comes from the independent colleges............And the better

colleges have by no means been injured by the growth of the

universities.''

Again, in another part of

the Report: We were constantly assured that many of the best students

in the universities come from the independent colleges, the small colleges

as well as the large."

And yet some say that Saint

Francis Xavier's College cannot hope to do good work because it is small.

Objections.

It is contended that if we

do not enter this merger, we shall be swamped. Why should we be? From all

that I have quoted it is evident that the small college can do just as

good Arts work as the large university. Against the cock sure declarations

of the merger-ites let me put the words of ex-President Harper of Chicago

University as given in "The Trend in Higher Education." He said "There

is no reason to suppose that the larger institution, however influential

it may become will supplant the smaller."

Burgess Johnson, assistant

professor of English in Vassar College speaks in the December 1920 number

of the "North American Review," of the inefficiency of the college courses

of the large universities and compares their work with that of the smaller

colleges. He writes: "No wonder the great universities seek to affiliate

with the small colleges of their neighborhood. Let us hope that the

Colleges will decline with thanks. The best passible antidote so far

discovered for the germ of educational elephantiasis, is the small

college."

2. Another argument for the

Merger is that degrees would be standardized, and also the courses leading

to degrees. If the Merger became a reality we should have higher education

dominated by one authority with probably a progressive intrusion by the

state. This is an argument against the Merger and not for it.

Progress depends not on moulding all in the same form but on allowing as

much freedom as possible in higher education.

Prof. Ross of the

University of Wisconsin, says in his Principles of Sociology: "The people

will be managed without their knowing it unless there are numerous founts

of authoritative opinion independent of one another and of any single

powerful organization. Let there be many towers from which trusty watchmen

may scan the horizon and cry to the people a warning which no official or

mob may hush." P. 436 Ύ.

"The higher means of social

control ought to emanate from many minds of divers experience and

interests." P. 433.

The case against the Merger

on this score is well put by Donald J. Cowling, Ph. D., President of

Carleton College. He says in an address: "I think we should all agree that

it is not desirable that all of the educational institutions of this

country should become of the same type or that their forms of development

should proceed along identical lines. There is room in this country for a

great variety of institutions; and educational progress and national

stability are better safeguarded by a multiplication of types than by a

standardized form which represents the views of some specialist as to what

a college or university should be. There must be ample opportunity for

variation and wide freedom for growth in different directions. The complex

needs of our one hundred five million people will be better served when

institutions grow up from the people rather than when they are imposed

from above, either officially by the government or unofficially by the

concerted action of the stronger types of institutions now holding the

field."

"There is reason to believe

that if Germany had had a greater variety in her institutions of higher

learning and particularly in the matter of their financial support, the

Prussian military regime would never have been able to secure a strangle

hold on them as it did and through them on the whole German system of

education." America is fortunate in having its higher education carried on

half by institution supported by the state and half by institutions on

private foundations, and I believe it is equally fortunate that the

undergraduate students of America are half in colleges associated with

universities and half in independent institutions with, no such university

relationship.

3. It is claimed that the

"modern requirements of good higher education," are so great that "to

perpetuate present arrangement therefore, is foregone defeat." If by good

higher education is meant university work the statement is probably true.

If college work it meant, the testimony of the best authorities goes to

show that the statement is false.

The Carnegie Report deals

with this subject under three heads, viz., (a) Cost of laboratories, (b)

Libraries,and (c) Professors' salaries.

The requirements of

laboratories in providing a good modern university education seem fabulous

no doubt when compared with the equipment of forty years ago. This is not

true of college work. According to the Report of the Association of

American Colleges, the value of equipment, outside of buildings, library

and heating plant for the minimum college should be $35,000. Surely there

is nothing fabulous about this.

The Carnegie Report

characterizes our equipment as "fair". With regard to (b) the Report says

that none of the New England Colleges already mentioned presumed to

operate with a working book collection of less than 100,000 volumes. Large

libraries are of course most desirable, but the library demanded by the

Association of American colleges for the Efficient College used not have

more than 25,000 volumes.

(c) With regard to salaries, the need for a "fabulous" increase in

salaries in the case of Catholic Colleges (and let us hope in the case of

the other christian colleges also) is not apparent.

The non-sectarian

universities must give fabulous salaries for the reason that fabulous

salaries are paid to motion picture actors, because of competition. But

Catholic colleges can get and keep their best men without resorting to the

jungle tactics of large corporations that are so characteristic of the

modern university.

No doubt the Catholic

college must pay those large salaries to laymen who are out for the most

they can get, but there should be enough zeal for christian education left

in the Catholic body to give a supply of teachers who are willing to give

their lives to the work for the love of truth itself.

Teachers surely should get

a decent living and enough to enable them to travel and to get their

sabbatical year, but experience and facts show that this salary need not

be fabulous.

On page 30 of the Carnegie

Report we read: "Yet the typical "small college" of New England, a college

such as Amherst Bowdoin or Williams, confined strictly to curricula in

Arts and Sciences, and doing comparatively little graduate work, has in

each of the cases mentioned nearly or much more than $3,000,000 of

endowment for approximately one-half of 1000 students."

Note well: The U. S. Bureau

of Education gives the following statistics for the New England

Universities and Colleges for 1918: Only 9 of the 47 institutions had

libraries of 100,000 volumes and over. Only 5 of the 47 institutions had

endowments of 3 million and over. Only 8 of the 47 had endowments of

$2,500,000. So much for the "typical small college of New England."

There are other

standardizing agencies besides the Association of American Colleges. In

our argument we have taken not the standardizing agency with the lowest

standards but one with the highest, the Association of American Colleges.

The National Conference Committee on Standards of Colleges and Secondary

Schools at its annual meeting, March 24, 1919, adopted the standard of a

productive endowment of $300,000. The North Central Association requires

an endowment of $200,000. A committee organized by the U. S. Bureau of

Education requires an endowment of $250,000. The Association of Colleges

and Secondary Schools of the Southern States requires an endowment of not

less than $300,000 and a library of at least 7,000 volumes. According to

the statistics of the U. S. Bureau of Education 400 colleges and

university libraries did not have in 1918 as many as 20,000 volumes. 77

per cent of the total number of institutions have fewer than 41,563

volumes. Only 42 of the 600 institutions have 100,000 volumes and over.

An examination of even the

state universities shows that only 16 of them have libraries of 100,000

volumes and over, while 28 of them have each fewer than 100,000 volumes.

Expensive equipment, large

libraries, and heavy endowments are necessary for the university and for

specialized work. It does not, however, follow that these are the

essentials of a college of liberal Arts. Good equipment is important but

it certainly is not so important as some would have us believe.

At a conference of the

American College held on the occasion of the anniversary of the founding

of Allegheny College, President W. P. Few of Trinity College had this to

say on this point: "The greatness of our College will depend upon the

elevation of the teaching profession does not depend upon higher salaries,

better technical training or more elaborate equipment but upon giving it

the proper dignity and importance in our life.....Hirelings can never give

the truest service."

And President William E.

Slocum of Colrado College at the same celebration said: "It was this that

Lord Bryce so strongly emphasized in his memorable address, when the

Rhodes Scholarships were established at Oxford, as he urged that there

should be the utmost possible degree of efficiency in equipment and

instruction for scientific education, but he insisted still more

strongly that to subordinate the interests of the humanities to those

of science is deliberately to dethrone the essential function of the

college. He said that there would be a scientific foundation for every

department of industry in its application to the arts of life, but said

that this is not the primary function of the college which has a much more

fundamental and essential part to play in the creation of the leadership

of the nation.

........It is not so much

what it (the college) teaches and how many subjects; but something it must

teach so that its graduates shall be strong to serve, and powerful enough

to battle the evil of the world, and construct virtue in the characters of

men and women.....If the American College loses sight of this sacred duty,

it becomes false to its trust, recreant and faithless before the most

essential of all the ends for which an educational movement can exist. All

attacking upon its function, all would-be modifications of its range and

scope, and of its four years of opportunity for study and spiritual growth

are the outcome of a misconception of the end which led to its

foundation."

"Lord Bryce's position is

the true one. There should be the utmost possible degree of efficiency in

scientific education; but to subordinate purely intellectual and moral

discipline to the interests of science is not only to dethrone the

essential interest of the college, but to miss the pre-eminent function of

education."

Attempts have been made to

befog the issue by quoting statistics with regard to the large endowments

and incomes of the American Universities. Since the testimony with regard

to the worth of the "small colleges" is so damaging, an attempt has been

made to make it appear that the small colleges of the United States have

endowments of millions, etc. What are the facts?

According to the latest

available statistics as given in the World Almanac for 1922 there are over

600 colleges and universities in the United States, and not 349 as was

stated in the Halifax Chronicle of Oct. 2. Of these 600 institutions only

109 have endowments over a million. 317 of the 600 institutions have each

fewer than 500 students, and of these 317 institutions with 500 and fewer

students only 16 of them have endowments of a million and over.

Notwithstanding the fact that there are in all the States heavily endowed

institutions there are hundreds of small colleges with a small number of

students and with small endowments. Philander P. Claxton says in The

American College, that in 1914 there were 328 colleges having working

incomes less than 50,000 dollars a year. How explain the existence of

these small colleges alongside so many large institutions? If the small

college is as inefficient as the Federationists claim it is in comparison

with the State Universities and the heavily endowed institutions, the

American people must lack ordinary intelligence.

A final bit of testimony

with regard to the advantages that the small college has over the large

university and we have finished with this phase of the subject. The late

Prof. Alexander Smith of Columbia University whose name is a household

word to all college students, wrote in Science, N. S., May 5, 1910: "In

respect to loss of time by overlapping, the university, with its numerous

instructors, is at a disadvantage when compared with the college. In the

latter, three or four years of chemistry are all given under the immediate

direction of one man, and continuous work and rapid progress by the pupil

are more likely to be secured."

From an educational point

of view, then, entering the merger would be a mistake. It would be

detrimental to the well-being of the country as a whole and especially to

the cause of Catholic education.

Education needs all the

resources it can command. Entering the merger would dry up many Catholic

sources of revenue. The same appeal for Catholic education could never be

made again. And with the disappearance of that appeal would go a great

opportunity to arouse Catholics and to unify them. Going into the merger

would mean practically the giving up of control of Catholic College

education. When the tail begins to wag the dog then will be ready to

believe that we can still control Catholic College work and enter the

merger. The social welfare of the country demands that our main source of

right principles and of christian leaders be kept intact and allowed to do

its work freely.

Religion and the Merger.

If the pedagogical and

social objections to the merger are serious the religious objections are

still more serious. True, many good Catholics see no objection in it, and

since Rome has not spoken in this particular case, the advisibility or

inadvisibility of entering the scheme must be judged on its merits.

It may be premised that the

fact that similar schemes are in operation elsewhere throws no light on

the subject. If the ideal cannot be obtained then the next best thing must

be tolerated. Now the ideal for Catholics is an efficient Arts course

carried on under Catholic auspices. If some people cannot themselves carry

on an efficient Catholic college then they must be satisfied with the next

best thing partial control of Catholic college work as obtains in

Toronto. And Rome at best only tolerates this when the most ample

safeguards are assured. The existence of tolerated plans of education

though should be no reason for trying to frustrate the attempts of others

to attain the ideal.

Now it is probable that the

education carried on at the Maritime University will be anything but

acceptable to Catholics.

According to the tentative

proposals put forward the greater and most important part of the work is

to be done by University Professors. It is reasonable to suppose that if

this consolidated university is to be a "Modern University" its teachers

will be somewhat like the professors of the modern university.

Consequently it is reasonable to suppose that much of the teaching done

will be of such a character as to be dangerous to faith and morals. Those

who advocate the merger either do not think that this teaching is morally

unsound, or, if they do believe that it is morally unsound, they must

believe that no harm can come to the students from having it given them.

If the first is the case, they know nothing about the social and

philosophical teaching of these professors. If the second, they are

putting themselves directly against the teaching of experience and of the

Church.

With regard to the first,

anybody who knows anything about non-sectarian university teaching knows

that it is saturated through and through with materialism. It is safe to

say that it is impossible to find a textbook in sociology or any of the

social sciences or in philosophy by a professor of a modern secular

university that is not built up on a materialistic foundation.

Here are one or two

examples of their teaching: "Man is not born human," says Prof. R. E. Park

of the University of Chicago, "it is only slowly and laboriously, in

fruitful contact, cooperation, and conflict with his fellows, that he

attains the distinctive qualities of human nature."

1. Prof.Conklin of

Princeton University says in Hereditary and Environment: "Intelligence

develops from trial and error." P. 48. "The phenomena of mental

development in man and other animals, etc. Page 55.

Profs. Park and Burgess of

the University of Chicago in their Introduction to the Science of

Sociology says: "There is no fundamental difference between intelligent

and instinctive behavior." Page. 80. Prof. Giddings of Columbia University

writes in Studies in the Theory of Human Society: "Man consciously has

ideas, and the higher animals perhaps have a few simple ones." P. 155.

2. Prof. Edman Irwin in his

work Human Traits and Their Significance says: "Given another environment,

his moral revulsion and approvals might be diametrically

reversed..........standards of good and evil depend on the accidents of

time, space, and circumstance." P. 425. Moral laws are not regarded as

arbitary and eternal, but as good in so far as they produce good." P. 431.

And Prof. Conklin of Princeton in Heredity and Environment page 322 says:

"We once thought that men were free to do right or wrong and that they

were responsible for their deeds; now we learn that our reactions are

predetermined by heredity, and that we can no more control them than we

can our heart beats."

"Conscience Codes" writes

Prof. Ellwood in his Introduction to the Study of Sociology, "are as

typical and characteristic products of social evolution as languages or

political systems.....A moral code instead of being a universal

requirement applicable to the treatment of all mankind, was first the

requirement devised by a group and inculcated and enforced, by a group for

the benefit of that group and its members. No man is born with a

conscience any more than he is born with a language." The freedom of will

is generally denied. "The balance of probabilities however, seems to favor

the opposite interpretation determinism." writes H. L. Warren, Princeton

University, in Human Psychology.

"They teach young men and

women plainly that an immoral act is merely one contrary to the prevailing

conceptions of society; and that the daring who defy the code do not

offend any Deity, but simply arouse the venom of the majority." (Bolce.)

And the reason is because they believe (to quote Profs. Park and Burgess

again); "Conscience is a manifestation in the individual consciousness of

the collective mind and the group will." P. 33.

"Religion is a social

product" Prof. Todd in Theories of Social Progress. "Religion had its

origin in the choral dance." P. 87, E. L. Earp of Syracuse University an

ex-minister is quoted as having said: "It is unscientific and absurd to

imagine that God ever turned stone-mason and chiseled commandments on a

rock.' Or, more generally, Religion is merely a human invention that

"assists control, and reinforces by a supernatural sanction those modes of

behavior which by experience have been determined to be moral i.e.

socially advantageous. Thomas, Source Book of Social Origins.

Dr. W. McDougall, Professor

of Psychology in Harvard University says in Body and Mind: "I am aware

that to many minds, it must appear nothing short of scandal that any one

occupying a position in an academy of learning other than a Roman Catholic

seminary, should in this twentieth century defend the old-world notion of

the soul of man.' (P. XI, ed 1920). Dr. McDougall is "the least prejudiced

of living psychologists" yet he has written of the freedom of the will:

"The fuller becomes our insight into the springs of human conduct the more

impossible does it become to maintain this antiquated doctrine," (Social

Psychology, p. 14.)

Prof. Todd has nine pages

on the disservice of religion. Here is a sample: "The clerical influence

in politics has almost invariably proved nefarious. In education even

worse. Dogmatic teaching is good discipline, but it seals up, nay, it

kills the mind. Speaking generally, in proportion as the mental influence

of a religion is wide, the outlook for individual advance is poor.....Such

schools (religious schools) are backward because they usually assume

religion to be the fundamental fact of life; whereas it is only one of the

elements which make up that indissoluble unity. They frequently represent

an antiquated notion of the family life. The family was held superior to

the state.' They tend to stultify the mind by holding to revelation

instead of to free inquiry."

.......'Andrew T. White, he

says, "demonstrates beyond cavil that theology has sought to block every

field of scientific advance.'

'With regard to marriage,

Prof. Giddings of Columbia University, the Dean of American sociologists,

teaches that "It is not right to set up a technical legal

relationship....as morally superior to the spontaneous preference of a man

and a woman."

Prof. Charles Zueblin of

Chicago University is quoted as having said "There can be and are holier

alliances without the marriage bond than within it.....Like politics and

religion we have taken it for granted that the marriage relationship is

right and have not questioned it." "The notion" Prof. Charles Sumner of

Yale says, "that there is anything fundamentally correct implies the

existence of a standard outside and above usage, and no such standard

exists." "Marriage secures better provision and training to children than

promiscuity"

says Prof. Thomas in his

Source Book of Social Origins. "The major prophet among them all, whose

name they speak with awed reverence, John Dewey, never misses an

opportunity to speak slightly of supernatural religion. His influence has

made Pragmatism the generally accepted basis of American educational

philosophy." (The Catholic Educational Review, Oct. 1922.)

Here is the experience that

one of the St. F. X. Professors had at Columbia University, New York. It

was in a graduate course on Value, a course in Economics, not in Ethics or

Philosophy. The Professor conducting the class was Dr. B. Anderson, who

later became professor of Economics Harvard and is now connected with one

of the large banking institutions of New York City. He said in substance:

All institutions, customs, and laws are human inventions derived for the

welfare of the group or society. Our matrimonial institutions, our laws,

ideas and customs with regard to the relationship that should exist

between the sexes are human inventions. They were derived at a time when

nothing was known about prevention of conception and the spread of

venereal disease. Our commandments and institutions were invented to

prevent the spread of disease and to safeguard the offspring. At present

conditions are different. Through the great advances that science has made

we know how to prevent the spread of these social diseases, and we know

how to prevent conception. The conditions that brought about our present

ideas and regulations with regard to the relationship that should exist

between the sexes have disappeared. He then asked the class: Seeing that

the reasons for our present views on those relationships no longer exist

how long will these views themselves last? The conditions that brought

about our present views on modesty, marriage, etc., have disappeared, when

will our present old-fashioned views go too? There were about twenty in

the class the majority of them teachers of Economics in colleges and

high schools. Not one of them disputed his assumptions with regard to the

origin of our present views on marriage, etc. Some of them said our

present ideas on these relationships, etc., are so old and so thoroughly

ingrained in us that it would take a long time to change them.

This professor merely

carried to its logical conclusion the ethical teaching that is given in

every non-sectarian university and a good many non-Catholic colleges in

the country. No wonder that Rev. Dr. George E. Hunt, Pastor of Christ

Presbyterian Church, Madison, Wis., is quoted by Dr. Crayne in his work

the Demoralization of College Life as having said: "If I did not live in

Madison, I never would send a young girl to the University of Wisconsin

or any other State University for that matter."

Clarence F. Birdseye in his

book "The Reorganization of our Colleges" says: "In many of our larger

colleges and universities, and too many of our smaller ones, a very

considerable part of the college home life is morally rotten terribly

so."

It is little wonder too

that proportionate to number there are more college men in the

penitentiaries of Ohio, Indiana and Illonois than there are of any other

class. There should be fewer because of their ability to get round the

law, pull, etc., but there are more according to an investigation made by

Prof. Murchison of Miami University and reported in School and Society for

June 4, 1921. He found 72 college men in these penitentiaries, while

according to the Law of Chance no more than 25 should be there. That is to

say, if college men were no worse than those of other classes, according

to their numbers there should be but 25 of them in the penitentiaries of

these states. Pro!. Murchison comments on these statistics as follows:

"The inference is very strong that college experiences are directly

responsible for the percentile increase in sex-crimes and crimes of deceit

and robbery.....This implies a lack of habitual thinking concerning the

inexorable laws of existence and development, etc."

The great danger of this

teaching is its insidiousness; bit by bit, through innuendo, raising of

doubts questionings, etc., faith is undermined. Their attacks are usually

not frontal ones. They may take the following form: "A desire for rain may

induce man to wave willow branches and to sprinkle water" P. 26. (Dewey,

Professor of Philosophy, Columbus University in Human Nature and Conduct).

Or as in Human Traits already referred to P. 455: "Those ascetics who have

denied the flesh may have displayed a certain degree of heroism, but they

displayed an equal lack of insight."

And Prof. Ross of the

University of Wisconsin says in his Principles of Sociology: "The Spanish

mind bears deep traces of the long emasculating servitude to which it was

subjected by its blind and bigoted loyalty to throne and altar." P. 518.

Again, "rigid ecclesiastical dogmas as to interest, almsgiving, marriage

and propagation simply cannot survive the light of social science. P. 508.

A writer in the "Catholic

Mind," for Aug. 22, 1916, who spent four years in a state university,

says: "As I view the matter the young man who expects to go through a

secular university with faith unshaken and morals unimpaired must possess

the courage of a saint, and the mental training of a Catholic Doctor of

Philosophy. He has enemies within and without the classroom and the

lecture-hall. He is surrounded by pagan servants, learned theorists,

superficial thinkers, men to whom tradition is a joke, the soul a myth,

and the spirit of reverence, which Carlyle sets down as a prime requisite

in a student, a mental and moral weakness."

Dr .Edward S. Young said

quite recently at the Bedford Presbyterian Church, Brooklyn: "What the

times demand is not fewer college men but fewer colleges that take the

religious convictions out of the youth who enter them. Practically all

your leading institutions of learning such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton,

Wellseley, etc., began as religious educational enterprises but many of

them have politely bowed the Almighty out."

And Right Rev. Bishop

Shahan, Rector of the Catholic University, says: "And in general, is it

not the professors of our modern secular universities who are responsible

for the vulgar materialism, the cheap hollow rationalism, the frivolous

pleasure philosophy, the irreligious and soon anti-religious hearts of

multitudes of modern men and women."

The quotations given

represent the views of the non-Catholic professors on the nature of man,

of economics, of religion and of morality. These views come to expression

not only in such classes as Philosophy and Sociology, but also in History

and the other sciences, even in Economics as has been said. They consider

their view of life the right one the Catholic one is mediaeval and

superstitious and they feel that they have a mission to enlighten the

benighted.

Another danger that would

result from the merger is the danger of an increase in mixed marriages

against which the Third Council of Baltimore issued a warning. That there

is a real danger here, cannot be questioned. Prof. Conklin, in his book,

"Heredity and Environment" says: "The President of a large co-educational

institution once said that if marriages were made in Heaven, he was sure

that the Lord had a branch office in His university." "I had occasion a

few years ago," Prof. Corklin writes, "to investigate the eugenical record

of a co-educational institution, which is not unknown in the world of

scholarship, and I found that about thirty-three per cent of the recent

graduates had married fellow-students, that there had been no divorces and

that there were many children. There is no doubt that co-education

promotes early marriages and that it is not necessarily inimical to good

scholarship, even though it violates the spirit of medieval monasticism."

Objections.

Much has been made of the

Toronto University situation. Father Carr, Rector of St. Michael's says:

"That our participation in the University will reduce teaching that

conflicts with Catholic views to a minimum, and that this alone is a big

reason for joining."

The modern professor looks

upon Catholicism as superstitious and as a relic of the Dark Ages. Do the

mergerites believe that these professors will be unscrupulous and cowardly

enough to keep their views to themselves because they will be afraid of

hurting the feelings of superstitious people? If the professors of

philosophy and of social science are not to say anything that conflicts

with Catholic teaching then they must give the antiquated Catholic

viewpoint or be false to their trust. These men have a mission to teach,

to enlighten, and it is reasonable to suppose that they will be faithful

to their obligations. If they are then they must say things that are

dangerous to faith and morals. The contention of the mergerites makes

cowards of them.

The President of St.

Michael's says that it is possible that bad teaching may be offered but

that so far they have had no reason for complaining.

It seemed strange that

Toronto should be so orthodox. To settle any doubts on the matter we

looked up the only Toronto University publication at hand, Prof. Mclvor's

Elements of Social Science, and we find there the same false teaching.

After giving the customary materialistic explanation of the history of the

family he writes: "Let us next observe the similar process which created

the Church.....The awakening ideals of the tribe creates gods of beauty,

like Apollo or Balder, and of the imperious attraction of sex, like

Aphrodite, As-tarte, Venus, and of motherhood like Isis and Demeter and

later of the Virgin Mother Mary."

How reconcile this ignorant

statement with Fr. Carr's statement? It is probable that the students of

St. Michael's being immature like most college students do not recognize

materialistic teaching when they hear it. This is a further reason for

keeping them from such places. Students in these universities

unconsciously imbibe false teaching without knowing it.

"The only thing we can do"

he writes, "is judge from our own experience and that of others, and from

our knowledge of men."

What does the man mean? You

cannot take a textbook treating of a philosophical or social topic and to

a great extent of many other topics whose whole philosophy is not

materialistic. Does he mean to imply that they write one thing in books

and teach something different in class? Sometimes they do, but in that

case what they give in class is usually much worse than what they write in

books. In such matters we cannot be guided by the experience of one or two

but by more general experience and by a knowledge of human tendencies.

It may not happen that

those professors will try to indoctrinate their disciples with their pagan

light and learning, but it is probable that it will happen. "Almost

anything is possible" writes Fr. Carr. What we should be concerned with is

not what is possible or here or there but with the tendencies that are

existent in human nature, and with what probably will happen. Now it

probably will happen that these professors will want the unenlightened to

partake of their enlightnment. "Bonum est diffusivum sui." It should not

be necessary to substantiate this with any authority other than common

sense, but it seems that it is.

Prof. Ross in his

Principles of Sociology speaks of social processes or tendencies and has a

whole chapter on one called Expansion "Throughout the social organization

of an enterprising people," he writes, "there is a marked tendency to

expansion. Officials press for more authority, etc."

"But there is another force

for expansion which may be called the proselyting spirit. This willingness

to take trouble to spread one's convictions and ideals, or to support

those who do it for one is praiseworthy because it is disinterested.

Furthermore it helps the valuable new thing to displace the sooner that

which is antiquated and affected............"

"Revolutionary

propagandists believe they have a Gospel to preach.....In their sense of a

mission to the suffering the great social artists resemble the founders of

the redemptive religions."

Mathew Arnold writes in

Culture and Anarchy, "Culture has one great passion, the passion for

sweetness and light. It has one even yet greater: the passion for making

them prevail.....The great men of culture are those who have had a passion

for diffusing, for making pervail, for carrying from one end of society to

the other the best knowledge, the best ideas of their time, etc."

If the professors of this

university are to be men of culture they will try to make prevail the

ideas that they believe. If they will not do this then they are

time-servers and craven, and even in that case are not fit to guide the

students under them.

But it is said that

colleges will counteract this teaching and have antidotes for it. How will

they counteract it? Will the professors of the colleges take each student

individually every day in the evening and go over the whole field of

history, psychology, and the social sciences and give the right answer to

the assertions of these material-isic professors? Hardly. Will they hold

classes corresponding to the university classes for the purpose of

combating errors given them? This does not seem very practicable. This

means a duplication of professors qualified to answer all the objections

of the University professors. How are the teachers going to keep track of

what is taught in the University classes? The students cannot always tell

them when wrong teaching is given. They know when we are called ugly names

but they cannot distinguish wrong philosophical teaching from correct.

This is no reflection on the student. It takes long training in Philosophy

and Theology to equip one with sufficient knowledge to distinguish between

what is true and what is false in university work. Even theologians have

been known to disagree as to what is heresy and what is not.

The students of a

university may be receiving instruction that is false and that will in the

long run undermine their faith without their realizing it. Any statements

made then about the absence of false teaching in any university must be

taken with a grain of salt. The probability is that a modern university

gives the philosophical and sociological opinions of the specialists in

these subjects and this teaching is materialistic through and through.

Even if the Toronto scheme

was the best for Toronto Catholics, it does not follow that it would be

the best everywhere else. We can cite an instance in which an experiment

was made similar to that of Toronto, and the results were so

unsatisfactory that the arrangement was abandoned.

Were we to enter the merger

the college would become little more than a residential hall. It would

have little control over the teaching of the last two years of the Arts

course, and these are the most important years of the course.

Dr. Cowling at the

inauguration of President Burton of Michigan University said:

"Furthermore, I think it may be justly maintained that is in the last two

years, and not in the first two, that a college accomplishes its purpose

with a student, and creates within him its distinctive ideal. It is not in

connection with the freshman mathematics, or beginning languages or

elementary sciences, that the college finds its real opportunity. The work

of these first years is largely a preparation for what the college has to

offer in the years to follow. It is only when the student begins to delve

into philosophy and economics and the social sciences, and when he begins

to understand the natural sciences in their implications and has developed

a real taste for literature and something of perspective in history, it

is only then that his personal philosophy of life begins intelligently to

take on final form." Two quotations along this line about the junior

college movement may not be out of place here.

President Rush Rhees of the

University of Rochester, says: "I believe that the American College

contributes to preparation for professional study an influence for

intellectual activity which no other agency has to offer. This service

cannot be so well rendered by an extension of the secondary school, after

the pattern of the German or French practice." (American College,

Crawford, p. 88, 89.)

President Slocum says of

the junior movement: "To yield to this new attack is but a step in the

path which leads ultimately to its (the college) obliteration and thus to

lose sight of the most important element in the educational movement in

America."

The most important years

then of the college course are the last two and these it is proposed to

give over largely to the University. It is in the last two years that

fruit begins to be seen, that the student begins to get interested and

show signs of progress. One result of the merger by the way would be that

the student would begin to contrast university work with college work and

to the disadvantage of the Catholic College.

It would be preferable as

far as Catholics are concerned to have the first two years done by the

university and the last two by the college.

According to the Carnegie

Report "The sophomore year would furnish a natural transition from this

largely intra-mural collegiate regime of the first year to the largely

extra-mural organization of the later years." The plan submitted by

Dalhousie for discussion reduces teaching by the colleges to very

insignificant proportions indeed. This memo for discussion is significant

of what we may expect if we put our heads in the merger noose.

According to the Dalhousie

plan the colleges will not be allowed to control the teaching in any

subject. They cannot teach even English and philosophy for more than two

years. They would not have complete control of the teaching of philosophy

for even two years as the professors of the subjects must be approved by

the University. The very sciences that should be under the complete

control of the colleges (at least of those few who believe in the validity

of their christian principles) are to be taken away from them altogether.

Education, psychology and the social sciences "must not be taught by the

college at all." Anyone with even the most meagre knowledge of these

sciences knows that they are bound up with ethics and religion. Pope Leo

XIII said that the social question is largely a religious question. And

still we are asked to hand over instruction in these sciences absolutely

to the university!

It may be said that the

proposals of Dalhousie may not be accepted. Perhaps not. But even the

proposals made show the trend of opinion in a very prominent quarter and

the lack of appreciation of the Catholic view point.

It makes little difference

whether a few subjects or many subjects are taught by the University as

far as the validity of this argument against the merger is concerned. If

teaching will be apportioned according to the memo submitted by Dalhousie

then we give up control of the most important part of the curriculum. If

on the other hand the colleges retain control over those subjects then we

do not get the supposed advantages of consolidation, and may as well stay

as we are. The more teaching we give up the greater the reason why we

should stay out. The more teaching we control, the less reason for going

into the merger. In either case whether we teach little or much the

argument against the merger is strong.

Some Catholics see no

danger in the merger. More important than the opinion of individual

Catholics is the mind of the Church on this question. But the teaching of

the Church as expressed in the decrees of popes and councils is against

non-sectarian teaching of this kind and consequently we should not give up

control of that part of higher education that we now control.

On Oct. 9, 1847, a letter

approved by Pius IX, was sent to the bishops of Ireland by the

congregation of the Propaganda with regard to attendance at secular

universities. Propaganda condemned the scheme although some bishops

favored it. "Monitos provide vomit Archie piscopos et episcopos Hiberniae

ne ullam in ejusdem excutione partem habeant........

Certerum S. C. probe noscit

quanti intersit adolescentium, civilioris praesertim coetus scientificae

instructioni consulere; provide Amplitudinem Tuam et suffraganeos simul

Episcopos hortatur ut media omnia legitinia quae in vestra sunt potestate

ad eamdem prom-ovendam abhibeatis. Curandum erit ut collegia catholica

quae jam constituata reperiuntur magis magisque floriant.

With regard to these three

colleges that were banned, Prof. Bertram Windle writes in the February

number, 1909, of the Catholic World "Even as it was, it was much less

non-sectarian or non religious, to speak more accurately, than university

institutions have since become; indeed in some respects, it permitted more

recognition of religion than is contemplated by the measure which has just

passed through Parliament. (Birrel's Scheme.")

The Congregation advised

the establishment of a university similar to Louvain. New representations

were made to the congregation by the supporters of the English scheme (and

some of the objectionable statues had in the meantime been removed) but

the Congregation reaffirmed its former condemnation.

True, this did not prosper,

but the reasons of this are known to all: As, E. A. D'Alton writes in the

Catholic Encyclopedia: "This want of harmony was conducive to enthusiasm

or efficiency." The Congregation of propaganda sent an encyclical letter

to the English bishops in which it was forbidden Catholics to attend

Cambridge and Oxford.

Pope Leo XIII in the

Encyclical Militantis Ecclesiae says: "We must take care that what is

essential, that is to say the practice of Christian piety be not relegated

to a second place; that while the teachers are laboriously communicating

the elements of some difficult science, the young students have no regard

for that true wisdom of which the beginning is the fear of God, and to the

precepts of which (wisdom) they must conform every instant of their

lives."

Leo XIII in this same

Encyclical expressly states, "that all the branches of teaching should be