|

Until comparatively recent

years, farming operation in the County of Inverness were necessarily

crude. The majority of our pioneer farmers had no opportunities for

agricultural training in the parent land. Rack-rent, feudal laws and

indifferent soil, reduced them to a state of living "from hand to mouth."

Many of them took to fishing and other callings rather than depend on

tilling the ground as lessees in summer. When they came here, the work

that awaited them was the removal of the forest. That was heavy manual

labor for which they were well fitted; but after the forest was cleared

skill and method were called for. Our forefathers possessed neither in any

advanced form. There were two reasons why they did not farm

scientifically. Firstly, they knew not how; secondly, there was no

inducement for them so to do. They were frozen out from all the world's

markets.

It is fairly correct to say

that, before the advent of railways, Inverness had no means of

transportation, and no home markets. Consequently, the old farmers had no

object in raising more than was actually needed for the upkeep of their

families. Fortunately, their cash calls were few, consisting chiefly of

"the taxes," Church dues, and the Schoolmaster's pay. The only places

where the farmers of this County could, in the olden times, convert any of

their products into cash were the islands of St. Pierre et Miquelon, and

St. John's Newfoundland. The shipping thither from these shores was quite

sufficiently interesting to merit a remark here. At a somewhat early date

Mr. Hubert, a Jerseyman, conducted a large general business at Arichat.

Thither, especially in Winter, farmers from the South-Western and Western

side of Inverness, often went with farm products to barter for goods

required in their homes.

Shipping day was an event.

It drew the whole countryside. A group of farmers had chartered a thirty

ton French schooner, which was standing off half a mile from the shore.

The export cargo was to be loaded by means of fishing boats propped up on

the beach, as far from the tide as they could be pulled. Now, these boats

were to be released for special duty, and pulled back into the sea by

sheer strength of muscle. A stalwart crew was assigned to each. Then the

owners of the cargo waded out to the boats with tubs of butter, bags of

wool, geese, pigs, sheep and lambs, all of which were deposited in the

waiting open boats.

Cattle and horses were a

different proposition. They could not be conveyed in these open boats;

neither could they fly nor walk on the water. Every steer, horse and

heifer, was caught and strapped with ropes around the head, shoulders,

back and body. By means of this rope-rigging each animal was towed out to

the vessel and there hoisted aboard, and lowered into the hold of the

ship, to begin its first and last sea voyage. Two men in the stern of each

boat took hold of the head of a steer apiece, holding it above water,

while four able oarsmen rowed away from the shore. When the cattle got

beyond their depth, they turned upon their sides and floated like oil

casks, the men in the stern of the boats holding their heads the while.

When the horses lost their footing, they swam away after the boats like

ducks at a regatta. Such a day for the boys!

If the gods were

propitious, and the winds favorable, that shipment might yield a

satisfactory return. If, on the other hand, a heavy storm intervened,

keeping that vessel blown and battered in the angry waters for weeks, the

full cargo might not realize enough to pay the incidental expenses.

Another possibility always remained, namely, that the whole outfit was

destined never to be heard of. Such were the hopes and fears of Cape

Breton commerce in the darker days that have be en. But a change hath

come. "Be ye thankful."

In the light of the past,

it is not surprising that Inverness County, as a farming community, should

have taken long to come into its own. A new era now awaits our own

judicious action.

The physical features of

the land are still against us in some places. We have ranges of mountains

and numerous hills, some of which are bleak and bald; we have deep ravines

and gulches where the plow can forever be a handy instrument of progress.

But we have a large section of rich, loamy land, and such fine

water-courses as River Inhabitants, River Dennis, the rivers of Mabou and

Skye Glen, and the splendid rivers of the Margarees. More than half the

county is capable of intensive cultivation. Our farmers are now working

with their heads. Modern methods and appliances are being used. Nearly all

the districts have their farmers Associations, and some of these are very

intelligently conducted. Some of our old farmers take short courses in the

Agricultural College at Truro, and some of our young men have entered upon

long courses in that and similar institutions. Our coal deposits may be

trusted to maintain industrial activities and good markets with the

county. Altogether, the outlook is good in Inverness for intelligent

tillers of the soil.

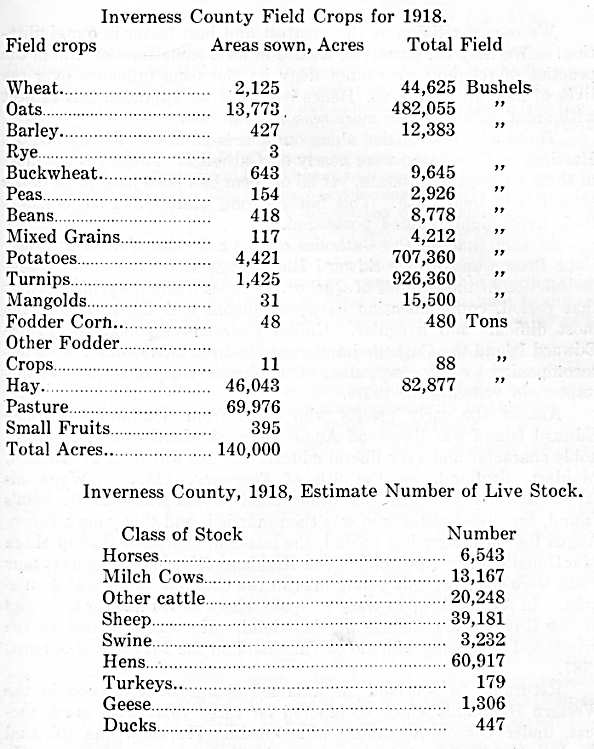

We take the following facts

and figures from the Nova Provincial Crop Report for 1918:

|