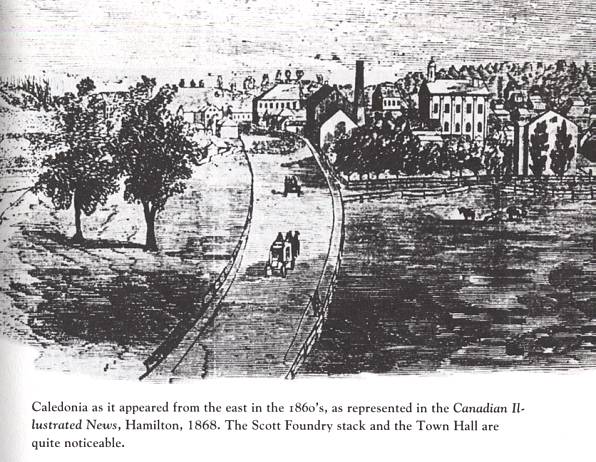

Caledonia’s early history includes the Caledonia

Foundry and Iron Works, better known as the Scott Foundry. Its huge stack

was dominant from 1854 to 1881.

The immense building extended from Edinburgh Square east, covering

the property where today three houses stand, across from the fairgrounds.

A stove once manufactured at the Scott Foundry is among the artifacts

exhibited at Edinburgh Square Heritage and Cultural Centre.

In its early days, with John Scott as owner, the

foundry manufactured all kinds of mill gearings and machinery in general.

Later, its advertising featured a complete assortment of ploughs, harrow

cultivators, horse rakes, threshing machines, stoves and other major

products as available. These advertisements were distributed across Canada

and the United States.

In 1862 a twenty-five horsepower

engine was sent to Oil Springs, USA along with two, 1,700 pound each, box

stoves designed for steaming purposes. At that same time the company was

manufacturing a circular mill to be shipped to Thunder Bay, Michigan, the

twelfth circular mill shipped out over a short period of time. Messrs.

Scott and Company were congratulated in the newspaper for not only

competing with American foundries, but surpassing them in the manufacture

of circular mills.

While mills and foundries were part of many small towns

getting their start in those years, the Caledonia Foundry and Iron Works

seemed to excel. In addition to building an export business, the foundry

looked to its local market and were responsible for the iron work on the

1875 Caledonia bridge.

During the same period, chair and furniture factories

were important businesses in many beginning villages. Caledonia was no

exception. The furniture factory owned by John Builder was in Caledonia,

while the chair factory operated in the village of Seneca.

A March 1987 City and Country Home

magazine article stipulated that rod-back dining chairs produced about

1850 in Caledonia area were still in existence as family heirlooms. Today,

there are homes in Caledonia still possessing household furniture and

chairs from that era.

Caledonia’s Gypsum History

"It took five tons of Caledonia’s Alabastine tinted

pink to spray Yonge Street in Toronto for the Easter Parade. And after the

parade it took Toronto firemen no time at all to

wash it down the sewers.

That bit of information is not generally known by

Caledonia residents who have taken the chief industry of the town for

granted since its beginning in 1905. But Earl Gillespie remembered that

and much more. He was an integral part of the plant from 1937

to 1982 in research, development, management

and technical areas.

According to the late Gillespie, the Grand’s old river

bed has everything to do with the discovery of gypsum deposits. Even the

Hagersville’s Canadian Gypsum Company mines, some ten miles away, are

considered a coincidental result of the Grand River Valley’s dried up sea

beds.

The story of the "plaister beds" or gypsum goes back to

1822 when William Holmes made the discovery on the banks of the Grand

River, about a mile below the town of Paris, Ontario. A plant was

established at Paris in 1896, and not long after, leases were taken out on

gypsum deposits below York in Haldimand. This led, shortly thereafter, to

the opening of the mine at Caledonia when gypsum was located there in 1905

while men were drilling for gas.

The gypsum rock was loaded into a one-ton car, hauled

to the surface by a horse and dumped into a storage bin. It was then moved

by wagon and donkey along a donkey track to the train, destined for Paris

for processing. That first mine provided employment for many Caledonians

over its more than fifty year span. Located just north of the plant and

under No. 6 highway, the mine is no longer in use.

The second mine is a little more than a mile to the

west of the first. The third location, now also being mined, is east of

the highway. This mine may eventually extend much further to the east

perhaps as far as the village of York.

Earl Gillespie remembered when it

took a month to train the horses and donkeys that pulled the cars along

eleven miles of track in the No. 1 mine. "Donkeys were used instead of

horses because they would drop their heads to refrain from hitting the

roof of the mine," he said. It was in the 1940’s that the four-wheeled

diesel-electric buggy came to Caledonia to replace the animals. It was

Earl’s responsibility to sell the twenty horses who had become friends of

the workers, but were no longer needed.

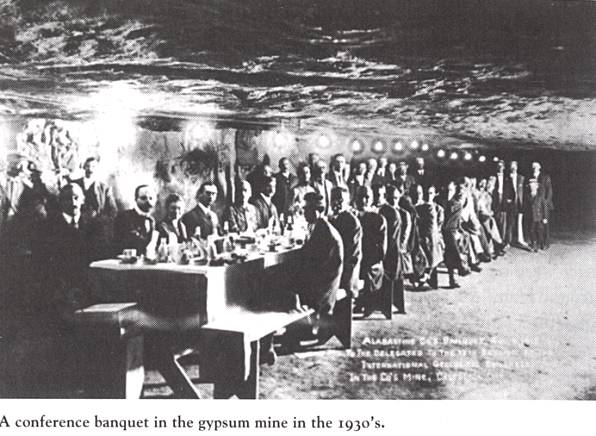

He also remembered hearing about banquets being held in

the mine during the very early years for some sixty people. Here the

company would often host dealers to promote products. "They must have been

rather cool affairs", he said, "the temperature in the mine remains at

55 degrees, winter or summer."

In the beginning, gypsum rock was ground to a fine

powder and used as a carrier. The original Tom Morrison family who came to

Caledonia from Scotland as stone dressers were skilled in using a hammer

and chisel. "It is a real art in dressing stones that made the powder,"

said Earl.

At one time, a by-product known as Alatint was sold on

the market as a Potato bug killer, in a pink or green colour. One year

it turned out to be grey. There were numerous

complaints from customers who claimed the grey powder didn’t do the job

nearly as well. Earl told this story with a smile. He also remembered a

Milton mushroom farmer bartering his truck load of mushrooms for a truck

load of gypsum, a valuable fertilizer.

"Many don’t realize that the Caledonia Plant was

responsible for setting up other plants in Canada and in other countries,"

said Earl. For instance the Montreal East plant was built under Caledonia

management to ship the Caledonia products to Scotland and England. The

Caledonia Plant also built sites at Rochester in Kent, England and in

Sheildhall at Glasgow, Scotland. Caledonia’s interest in both plants were

later sold out to British Gypsum. Both are now owned by Westroc, a

competitor of Domtar.

There were some one hundred and twenty-five employees

in 1937 when Earl first joined the company, mainly residents of the town.

But during World War II, people had to be brought in from other parts of

the country. As Earl recalled, many came from Westinghouse and Stelco who

were on strike at the time.

The war had a big effect on the Caledonia plant when

wartime industries were needed. Hundreds of wartime houses were built very

quickly around Hamilton and area with the new wallboard being produced at

the Gypsum plant. Caledonia was the first to manufacture wallboard. Since

1916 it has been the chief product and today remains the primary product

of the gypsum produced by Domtar Gypsum.

Another wartime effort included working with Fleet

Aircraft to develop a formula of a mixture of Lumnite Cement and Plaster

of Paris to produce the molds for the fenders of the Fleet aircraft. As

well, the floors of all the arsenals used in Canada during the war came

from the Caledonia plant. In addition, the Caledonia plant was one of the

first manufacturers of Rock Wool when they used slag from Stelco in the

production of insulation.

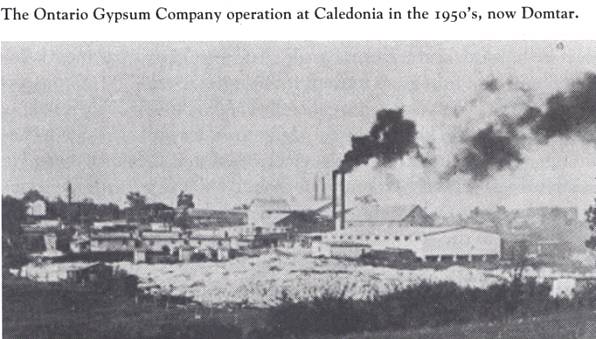

One of the three biggest companies in North America,

Domtar Gypsum, as the company is now known, has been very aggressive in

the last few years with takeovers in the United States.

The Caledonia operation expanded in 1979 to include a

second plant on the east side of No. 6 highway. Today, it employs

approximately two hundred people. The Edinburgh Square Heritage and

Cultural Centre at Caledonia’s old town hall houses the only museum in

North American that claims to tell the story of gypsum. Earl Gillespie, as

the Chairman of the Board for the Centre, was instrumental in ensuring

that the story of this major company would be available to the public.