|

From the Haldimand Grant to the Grand River

Navigation Company

Caledoniaís story begins with the aftermath of the

American Revolution. On October 25, 1784, the British Crown gave Mohawk

Chief Joseph Brant and his Six Nations Confederacy six miles of land on

either side of the Grand River beginning from its mouth at Lake Erie to

its source in present-day Dufferin County. This land grant was given in

gratitude for their services and loyalty to the Crown during the American

revolutionary war and in response to their application for recompense for

their lands lost to the United States.

The

grant was completed by Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor-in-Chief of

Canada, after whom the county is named and subsequently the entire

regional municipality. That same year Chief Brant invited some white

Loyalist friends who were refugees from the Revolution, to settle with him

in the Grand River Valley. In turn Brant gave them tracts of land along

the river. The

grant was completed by Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor-in-Chief of

Canada, after whom the county is named and subsequently the entire

regional municipality. That same year Chief Brant invited some white

Loyalist friends who were refugees from the Revolution, to settle with him

in the Grand River Valley. In turn Brant gave them tracts of land along

the river.

One of these friends was Henry

Nelles and his sons. They were allotted a block in Seneca Township, three

miles back from the river bank and three miles broad, plus a small tract

in Oneida on the south side. Adam Young and his sons were also given a

large tract in Seneca further east beyond York, a village along the banks

of the Grand. There were no roads or easy access and no improvements in

the area. The Nelles and Young families began the back breaking labour of

clearing the land by hand. Later others would come and settle mainly

around Oneida.

Shortly after 1830 the government,

with the consent of the Chiefs, decided to sell all the remaining portions

of the reserve in Haldimand, except for a small section in Oneida, and

open this area for development. The proceeds were to be invested for the

benefit of the Indians, with the interest on the investment being paid in

goods such as guns, blankets, and ammunition. Consequently, a treaty was

concluded that resulted in the surrender of the lands to the government

and the opening up of the townships for white settlement.

In

1832 a bill was passed by the provincial government authorizing canal and

lock building on the Grand, or Ouse River as it had been known. The

success of the Rideau Canal and the new Welland Canalís feeder line to

Dunnville had opened up the Grand, making commercial navigation possible.

Already the Dunnville Dam, which had been built in 1829, allowed boats to

travel through Cayuga to the nearby village of Indiana. In

1832 a bill was passed by the provincial government authorizing canal and

lock building on the Grand, or Ouse River as it had been known. The

success of the Rideau Canal and the new Welland Canalís feeder line to

Dunnville had opened up the Grand, making commercial navigation possible.

Already the Dunnville Dam, which had been built in 1829, allowed boats to

travel through Cayuga to the nearby village of Indiana.

In the entrepreneurial spirit of the

time The Grand River Navigation Company was formed. With John Jackson as

engineer, more dams, canals and locks were to be built. Travel on up the

river from Indiana to Brantford could be made possible. Timber, gypsum and

grain products would move more rapidly. By 1833 dams one, two and three

were completed at Indiana, York and Sims Locks. Dam four, just east of

what we know as Caledonia today, was in place in 1834.

The Navigation Company laid out small villages on north

and south banks of the Grand. The village of Seneca was located on the

north bank at Dam four, while the village of South Seneca was on the south

bank. By 1834 Jacob Turner, the contractor for dam four, was operating a

sawmill at Seneca Village. Settlers were beginning to establish other

businesses in both the north and south sites. Dam five, about a mile to

the west at Oneida, was yet to be built. Once Ranald McKinnon was assigned

as the contractor, he built a sawmill on the north bank right at that

location as was the practise of the time. This marked the beginning of the

village of Oneida on the north bank and Sunnyside on the south bank.

When McKinnon first arrived in the

area he came upon Bryantís Corners, a hamlet consisting of two log houses

and a tavern owned by Mr. Bryant. Today, Bryantís Corners is the main

corner of Caledonia at Caithness and Argyle Street, midway between what

was then Seneca Village and Oneida Village.

Thereís More To The Legend:

Captain John Norton

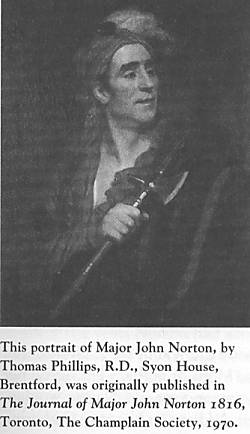

He deserved more acclaim than he was

given. He did not deserve the legendary inaccuracy he received. A story of

John Norton, passed down through the years and written under the title of

The Last Duet in Canada created some widespread notoriety, but

there was much more to John Norton than the duel fought in the latter

stages of his life.

Captain

John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen) was born about 1760 to a Cherokee father

and a Scottish mother in the country of the Cherokees. In 1795 he arrived

at the Grand River settlements to be an interpreter among the Grand River

Indians. His years of education in Scotland, his linguistic abilities and

personal flair had prepared him for leadership with his people. Captain

John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen) was born about 1760 to a Cherokee father

and a Scottish mother in the country of the Cherokees. In 1795 he arrived

at the Grand River settlements to be an interpreter among the Grand River

Indians. His years of education in Scotland, his linguistic abilities and

personal flair had prepared him for leadership with his people.

In 1823 when John Norton was about

60 years old, he owned Hillhouse, a mansion of the day located atop a hill

along the Grand River just east of what is now known as Caledonia. By then

he was a prominent citizen accepted as a Mohawk of the Grand River

community and highly respected among those he lobbied in England on behalf

of the Indian nations. But he left after the duel fought at Hillhouse,

never to be heard of again.

It wasnít until 1970 when the

Champlain Society of Canada published The

Journal of John Norton 1916, edited with

introductions and notes by Carl F. Klink and James J. Talman, that the

full Norton story became known. The Champlain Society was given permission

to print the manuscript by His Grace, the tenth Duke of Northumberland.

Captain Norton had been commissioned

by the second Duke of Northumberland to write this journal while

documenting a journey of a thousand miles down the Ohio in 1809. In this

account he described the Five Nations as well as describing his way to the

Cherokee country of Tennessee in 1809-10 and recorded his campaigns in the

War of 1812-14. Nortonís journals are published in two volumes with forty

pages given to a table of contents and a dedication to the second duke,

nine hundred and sixty-seven pages for text and twenty-three pages of

vocabulary.

By 1799 Joseph Brant had conferred

the title of war chief upon him. It is said that his accomplishments

exceeded Brantís anticipations as Norton lobbied on behalf of the Indians,

taught them agriculture and dealt with their land claims. Following Joseph

Brantís death on November 24, 1807, John Norton became their respected

spokesman and leader.

Nortonís exceptional career

encompassed the difficult early history of Upper Canada. Especially

complicated were dealings concerning the place of the Six Nations, their

land claims and the lobbying that had to be conducted with the British

Government during Joseph Brantís time and after.

One description of Norton tells us

that he spoke the language of about twelve different Indian nations, as

well as English, French, German and Spanish, and that he was an avid

reader in possession of all the modem literature of the day. Another said

he was a man of great natural acuteness, possessing much reflective

ability united with a sense of religion and an ardent devotion to the

interest of his tribes. A physical description tells us that "he was 6

feet tall, well made, active, possessing a dark complexion, mild with

pleasing manners and prone to wearing clothes of English fashion."

On July 27, 1813 immediately following the War of 1812,

Norton wed Catherine Munn (also known as Maus, Mons or perhaps Docherty;

her native name was Karighwaycagh), a sixteen year old Native woman. They

were married by Reverend Robert Addison in Niagara. Catherine had been

brought up by her grandmother along the Grand River. Her father was said

to have been white. Norton took Catherine and his ten year old son John

from a previous marriage, to Dunfermline, Scotland where they attended

school in the care of Mr. and Mrs. Johnstone, friends from Nortonís own

hometown. Young John was to stay to complete his schooling while Catherine

returned to Canada with her husband in 1817.

That year Captain Norton promised

Reverend Robert Addison, the Anglican missionary with the Church of

England to Niagara and the Indians at Six Nations, that he would translate

the gospels of the Bible into Mohawk. Although he had completed the

translation of St. Matthew by 1821, he was worried that the rest would be

of little use and did not complete the task. Later Aaron Hill and Dr. John

Strachan would finish the work begun by Norton.

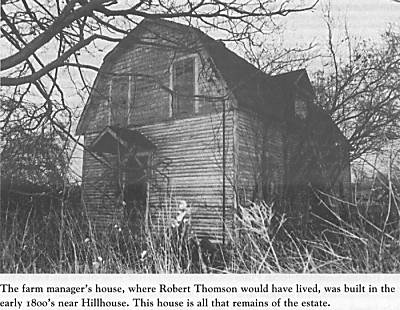

Over the years Norton had acquired a

large tract of land of about 925 acres overlooking the Grand River below

Caledonia which we know today as the area of Sims Lock. This is where

Hillhouse was built for him and his wife. The farm managerís small log

house still remains as a reminder of its history. Today, the road (Highway

54) is to the south of the log house. However, when Hillhouse was

just a few feet west of the log house, the road ran north of the house. It

was here that the duel was to be fought.

The story of the so-called ĎLast

Duel in Canadaí begins when Nortonís life took an unfortunate turn at

hay-making time in 1823. His debts had been increasing to the degree that

the Third Duke of Northumberland had paid for young Johnís education.

Depressed by his lack of funds and his corresponding inability to travel,

he was growing restless and feeling limited in his role as farmer. Over

the years he had enjoyed being a celebrity, called upon to verify war

records of Indians and settlers and recommended by influential friends to

those seeking advice. Now his life was restricted and confining.

One day Catherine complained to her

husband of a young man making advances to her. The distraught Norton

abruptly sent notice for both of them to leave the area. The Champlain

Society published word for word, John Nortonís own account of the incident

as written in a letter to his friend, Colonel John Harvey, a veteran of

the War of 1812. He began by saying an unfortunate affair had occurred at

his place that had filled his heart with vexation and grief. The young man

his wife had complained about was Joseph Big Arrow, a person Norton had

affectionately fostered from childhood.

Neither individual had obeyed

Nortonís notice. When the young man came to the house, Catherine rushed

downstairs and accused him to his face, "upbraiding my moderation", said

Norton. He didnít exactly remember what he said, but he knew he felt angry

yet reluctant to hurt him. When the young man dared Norton, Norton told

him to choose his weapons, noting in his letter that the young man should

have an equal chance. As he took his pistol and prepared

it, Norton noted

that there were several people standing by.

"I told him that when he took aim at

me and I saw him ready to fire I would treat him as I did my enemies ó he

advanced taking the rising ground on one side until within three paces,

when he presented at my head: after firing, it appears he sprung upon me:

and had seized or in some manner changed the direction of the pistol for

the ball passed downward and through his thigh, while his ball grazed the

top of my head." This Norton described in the letter.

According to the trial transcripts,

Joseph Big Arrow of Bearfoot Village on the Grand River, died about

forty-eight hours later. Witnesses were reported to have said that Norton

lamented at what had happened and was heard to say, "Oh, my Joseph."

His letter expressed his ongoing

feelings of pity and distress and identified that on the third day friends

told him he should leave home in anticipation of a change of situation

which might afford relief of mind. He told Colonel Harvey that he had

written to the Attorney General offering himself for trial, naming as many

witnesses as he had remembered. He also stated that he was going to take a

young Cherokee friend to his country where he would remain for the winter,

a trip he had been wanting to take.

Although Norton had not named the

young man he had challenged to a duel, his son John, by this time a young

man himself, in writing to his father to tell him to leave because of the

familiesí embitterment, indicated that the fellowís English name was

Crawford. John had also proposed that a settlement be made to the injured

family as it

was an Indian custom.

Following his trial in Niagara,

Norton described the proceedings for Colonel Harvey saying he had been

kept in prison until the verdict was announced; a fine of twenty-five

pounds. Big Arrow, (Joe Crawford) had left a widow and two children. He

noted that Big Arrowís pension might be allowed to continue to his family

for a little time.

Norton refused to see his wife.

Catherine wrote to him on August 3, 1823 pleading that he not believe all

that people were saying against her. She had left with only a blanket. A

trunk had been sent to her later with many things taken out. She said she

had heard they wanted to kill her, but that she believed it was all false.

She wrote, "God forgive me my sins, I will never forget it all the days of

my life." She ended by saying she hoped Norton would not forsake her all

together and asked again for his forgiveness.

There is evidence to conclude,

according to The Journal, that Norton had directed his pension to

Catherine, with the last payment made on February 25, 1826. There is also

evidence to conclude that Catherine went to Moraviantown on the Thames

River which is in the St. Thomas area of today. She died January 16, 1827.

The Niagara Gleaner printed

the account of the trial on September 20, 1823. It said Norton would no

doubt have been acquitted altogether if he had not, from feelings of

delicacy, withheld his best defense.

Norton left for Cherokee country

following the trial, where it

is believed he lived until his death in October 1831.

Hillhouse Farm was looked after by the farm manager, Robert Thomson, until

1838 when Charles Bain purchased the land from the government. The

surrender document, which the Bain family still have in their possession,

is signed by forty Indian Chieftains. The money from the sale went into a

fund on which the Indians drew interest. The original home burned in 1838

and in 1840 the present house was built.

John Norton Jr. returned to Canada

to live on the Huff Tract near Cayuga where he had received a patent from

the Crown for 388 acres. On August 3, 1840 he sold this property and moved

to Thamesville.

A memorial to Captain John Norton

was placed in a stained glass window of the historic Mohawk Chapel in

Brantford where it can be seen to this day. The inscription reads,

"installed with the gracious approval of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to

commemorate the special association for the Chapel of the Mohawks with the

Royal Family. Dedicated on May 27, 1962, the 25th anniversary of the gift

of a Bible ĎTo Her Majestyís Chapel for the Mohawksí by Queen Anne in

1712, this window portrays the distribution of the Gospels in Mohawk in

1806."

"Let us strictly adhere to what our

Lord has transmitted to us in the Holy Scriptures, that thereby the

unbelievers may know the love we bear the commandments of God. Preface to

St. Johnís Gospel ó Captain John Norton." |