|

A paper presented at the Burns in the Scottish

Diaspora Conference, Napier University, Edinburgh, July 2009 and at

the 2009 Scottish Studies Fall Colloquium, University of Guelph,

September 2009.

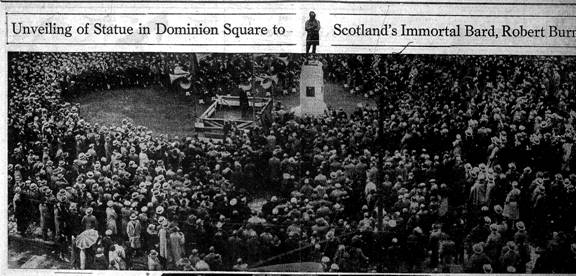

Figure 1. Montreal Daily Star, 20 October 1930, page 3.

Introduction

On a cold and rainy October day in

1930, Montreal’s Scottish community unveiled a statue of Robert

Burns in the city’s downtown Dorchester Square. The statue was a

reproduction of the one which stands in Ayr, near Burns’

birthplace. Its erection was not only in honour of Burn’s genius,

but also to commemorate the impact of Scots on Montreal’s

development. The speeches made that day emphasised that point.

Burns was a symbol of Scottish

identity in 1930s Montreal. The utilization of Burns as such was

not a sudden thing. It evolved over the nineteenth century,

competing with other symbols of Caledonia within Montreal ‘s

Scottish community for pre-eminence.

This study will trace the development

of Montreal’s Scottish community through its public celebrations,

commemorations and voluntary associations, and their use of Robert

Burns within them. It begins in 1801, the date of the first Burns’

supper in Edinburgh, and ends in 1875. These public events and

institutions featured in the city’s English-language press, and

reflect the changes in Scottish identity, and their representations

over these seventy-four years.

Figure 2: Population of Montreal by Place of

Birth.

Scots have never been a large

percentage of Montreal’s population, averaging between six and ten

percent in the period under discussion. This chart shows that while

the English-speaking population were the majority of the city’s

population between 1832 and 1871, as a national group, French

Canadians were always the majority. Among the Anglophone groups in

the city the largest national group were the Irish, who numbered

between eighteen and twenty-five percent of the population.

A lot of the historiography dwells on

the over-representation of Scots among the city’s political and

economic elite. And while this is true, it does not mean that all

Scots operated in this group. The vast majority of Montreal’s Scots

occupied the less rarefied air of the middle and working classes.

National Identity

In 1807, the Montreal Curling Club

was founded. It was at its heart a national association which,

until about 1820, limited its membership to those of Scottish

origin. Curling was not only a pleasant way to spend a frozen

afternoon in the great outdoors, but a means of promoting Scottish

identity. The events not only utilised the curling itself, but also

other symbols of Scotland, particularly bagpipes.

The competitors walked in procession

to and from the ice and tavern, accompanied by pipes. At the

tavern, after the games, they toasted the day along with Scotland

and its heroes. This account of curling, which appeared in the

Herald in 1824, underscored the presentation of curling as

Scottish:

After being divided into

two parties for the games of the day,

and their chiefs being appointed, the Rules

were repeated by

their host, Mr. Hector McEchearn, and they

proceeded to the

scene of the action on the river, headed

each by their National

Music, that instrument which gives

enthusiasm to their joys, and

Heroism to their duty- which inspires their

ancient hereditary

merriment, mixed with those remembrances of

their country and

its past story, and softened by

recollections of the “many braw lads

it has whistled to their grave.”

The first half of the nineteenth

century was marked by the development of St. Andrew’s Day

celebrations. The city embraced the use of patron saints to

celebrate the various national identities present. One newspaper

called this the “brotherhood of saints.”

The English were the first to use

their patron saint, George, in 1808. They held an elaborate dinner

which lasted a full day, and utilised St. George excessively as

decoration, on the food, walls and in the toasts. Other groups

followed suit.

The Scots, following the first

successful St. David’s Day in March 1816, undertook the organisation

of the first St. Andrew’s Day, in November 1816. Like the other

groups had before them, the occasion was marked with a dinner, full

of toasts and traditional dishes. It was followed by a ball. The

Herald described it thus:

The dancing commenced

about 7 o’clock and continued

with great spirit till after midnight, when

the company to

the number of 150 sat down to a sumptuous

and elegant

supper. . . The supper room was handsomely

decorated for

the occasion having at the upper end a

transparency

representing St. Andrew at full length.

After supper the

dancing was resumed and continued with much

vivacity

till after five. . .

St. Andrew’s Day was not celebrated

regularly until the 1830s. When it was celebrated in the 1820s it

was in various ways, balls, dinners and sometimes both. In 1825,

the Theatre Royal produced the play “Wallace” and illuminating the

building with a large transparency of the patron saint.

The St. Andrew’s Society was formed

in late January 1835, following in the footsteps of the St.

Patrick’s Society and the St. George’s Society. The German Society

came soon afterwards. These societies institutionalised the

celebration of saints’ days, and regularized the way in which they

were celebrated. A parade and church service were added to the day,

employing the same forms of celebration that the Irish had been

using since 1824.

But what of Robert Burns? He

appeared in accounts of St. Andrew’s Day as the subject of toasts.

In 1820 he was number of 18 of 19 toasts: “The Memory of Robert

Burns, our Rustic Bard.” Often though, he shared the honours with

Sit Walter Scott, but was also known to accompany Wallace, Bruce,

Knox, and Ferguson. “Auld Lang Syne” was often sung at the dinners

too.

In 1840 a number of St. Andrew’s

Society members came together and purchased a bible which had been

reputedly given to Highland Mary by Burns in 1786. They promptly

donated to Burns’ birthplace in Ayr. Burns was obviously not out of

the consciousness of Montreal’s Scots, but was second fiddle to the

patron saint.

By the 1840s, Montreal’s population

had grown enormously, providing the labour for its rapidly

industrializing economy. The city’s associational life had

expenaded to accomadate these new residents. The St. Andrew’s

Society was joined by the Caledonian Society in 1855, and the

Thistle Society in 1857. These Scottish societies joined the St.

Andrew’s Society in celebrating the saint, in their parades,

services and dinner.

In 1851, Robert Burns’ birthday was

celebrated for the first time in Montreal. Not by any of the

previously mentioned Scottish societies, but by the Caledonian

Curling Club, founded the previous year. The date was chosen for

the club’s annual dinner of beef and greens. They chose the date

because it was Burn’s birthday. The club members toasted Burns that

year. In subsequent years, the Caledonian Curling Club continued to

use the same date, but ceased to toast Burns.

The centennial of Burns’ birth in

1859 marked a more concerted effort on the part of Montreal’s Scots

to use Burns as a rallying point for their community. The Burns

Club, a specially formed committee, organised a banquet at the

City’s Concert Hall. Close to a thousand men and women paid 6

shillings to dine, hear speeches, sing and toast Burns, in an

elaborately decorated room.

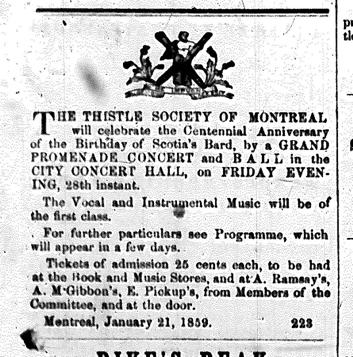

Figure 3: Montreal Witness, 21 January 1859.

Three days later, in the same venue, an unknown

number paid 25 cents for a promenade concert and ball, hosted by the

Thistle Society. The Thistle Society continued to host a promenade

concert and ball on Burns’ birthday until 1862. The Caledonian

Society took over the day in 1869. Instead of concerts, which

attracted large mixed crowds, they male-only dinners with smaller

numbers of attendees.

It would be a mistake to think that

Scots’ celebrations in Montreal were limited to these two days.

Montreal Scots adapted their celebrations to local needs. They used

Burns’ poem “Halloween” as inspiration for another commemoration.

October 31st was considered a traditional celebration in

Celtic cultures, but had not been mentioned in Montreal in any way

until 1860, when the Caledonian Society decided to host a “Grand

Scottish Entertainment.” They were, at this date, already

responsible for the Highland Games, held every summer, but had no

winter gatherings.

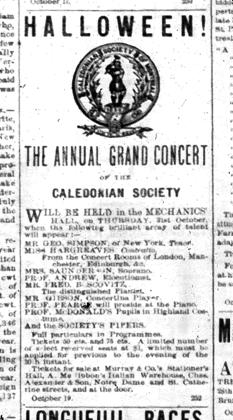

Figure 4: Montreal Witness, 19 October 1860.

The program included Scottish ballads

and instrument solos, lectures on Burns, and from 1886 on, prize

poems. The event attracted around 2000 spectators each year.

All the celebrations that I have

presented expressed a Scottish identity formed from their

experiences in Montreal. In Halloween there was a clear connection

between old world and new. Speeches, like the excerpt below, and

the prize poems like “Canadian Patriotic Song,” emphasised both

their Scottish roots and their Canadian lives.

This is one of those

occasions when Scotchmen in

are wont to look back through the years and

distance

which intervene towards the land of their

birth, and to

recall his treasured memories and

traditions. May we all

do so to night, at the same time not failing

to remember

with gratitude and affection Canada our

home.

Conclusion

There came to be three specific days

in which Scots in Montreal could express their identities publicly:

Burns Night, Halloween and St. Andrew’s Day. Of the three, two were

associated specifically with Robert Burns.

The memory of Burns can

be honored by the

lowliest in their lowly manner, with quite

as

much sincerity as by the lordly,

ostentatious,

wealthy few.

As the Pilot stated in 1861,

above, Burns was a popular figure, who lent himself to the elite and

non, alike. The elites used Burns night, while the others used

Halloween to express Scottishness. Burns had graduated from a

symbolic toast to the central figure in the community’s

celebrational life.

You can also read more of her work at

http://gilliandr.wordpress.com |