Few of the villagers were

astir; and at the first he met—who carried a spade over his shoulder, and

appeared to be a ditcher—he inquired if he could show him the house in

which the bard and scholar was born.

"Ou, ay, sir," said the

man, "I wat can I—I’ll show ye that instantly, and proud to show you it

too."

"That is good," thought the

stranger; "the prophet is dead, but he yet speaketh—he hath honour in his

own country."

The ditcher conducted him

across the green, and past the end of a house, which was described as

being the school house, and was newly built, and led him towards an humble

building, the height of which was but a single story, and which was found

occupied by a millwright as a workshop. Yet, again, the stranger rejoiced

to find that the occupier venerated his premises for the poet’s sake, and

that he honoured the genius of him who was born in their precincts.

"Dash it!" [This was a

common expression of Leyden’s, and, perhaps, was to some degree expressive

of his headlong and determined character.] said the stranger, quoting the

habitual phrase of poor Leyden. "I shall fish none to-day." And I wonder

not at his having so said; for it is not every day that we can stand

beneath the thatch-clad roof—or any other roof—where was born one whose

name time will bear written in undying characters on its wings, until

those wings droop in the darkness of eternity.

The stranger proceeded up

the Teviot, oftentimes thinking of Leyden, of all that he had written, and

occasionally repeating passages aloud. He almost forgot that he had a rod

in his hand—his eyes did anything but follow the fly, and, I need hardly

say, his success was not great.

About mid-day, he sat down

on the green bank in solitariness, to enjoy a sandwich, and he also placed

by his side a small flask containing spirits, which almost every angler,

who can afford it, carries with him. But he had not sat long, when a

venerable-looking old man saluted him with—

"Here’s a bonny day, sir,"

The old man stood as he spoke. There was something prepossessing in his

appearance. He had a weather-beaten face, with thin white hair; blue eyes,

that had lost somewhat of their former lustre; his shoulders were rather

bent; and he seemed a man who was certainly neither rich nor affluent, but

who was at ease with the world, and the world was at ease with him.

They entered into

conversation, and they sat down together. The old man appeared exactly one

of those characters whom you will occasionally find fraught with the

traditions of the Borders, and still tainted with, and half-believing in,

their ancient superstitions. I wish not to infer that superstition was

carried to a greater height of absurdity on the Borders than in other

parts of England and Scotland, nor even that the inhabitants of the north

were as remarkable in early days for their superstitions, as they now are

for their intelligence, for every nation had its superstitions, and I am

persuaded that most of them might be traced to a common origin. Yet,

though the same in origin, they change their likeness with the character

of a nation or district. People unconsciously made their superstitions to

suit themselves, though their imaginary effects still terrified them.

There was, therefore, a something characteristic in the fables of our

forefathers, which fables they believed as facts. The cunning deceived the

ignorant— the ignorant were willing to deceive themselves; and what we now

laugh at as the clever trick of a hocus-pocus man, was, scarce more

than a century ago, received as a miracle—as a thing performed by the hand

of the "prince of the powers of the air." Religion without knowledge, and

still swaddled in darkness, fostered the idle fear: yea, there are few

superstitions, though prostituted by wickedness, that did not owe their

existence to some glimmering idea of religion. They had not seen the lamp

which lightens the soul, and leadeth it to knowledge; but, having

perceived its far-off reflection, plunged into the quagmire of error—and

hence proceeded superstition. But I digress into a discant on the

superstitions of our fathers, nor should I have done so, but that it is

impossible to write a Border Tale of the olden time without bringing them

forward; and, when I do so, it is not with the intention of instilling

into the minds of my readers the old idea of sorcery, witchcraft, and

visible spirits, but of showing what was the belief and conduct of our

forefathers. Therefore, without further comment, I shall cut short these

remarks, and simply observe, that the thoughts of the young stranger still

running upon Leyden, he turned to the elder, after they had sat together

for some time, and said—"Did you know Dr. Leyden, sir?"

"Ken him!" said the old

man; "fifty years ago, I’ve wrought day’s-work beside his father for

months together!"

They continued their

conversation for some time, and the younger inquired of the elder, if he

were acquainted with Leyden’s ballad of "Lord Soulis?"

"Why, I hae heard a verse

or twa o’ the ballant, sir,’ said the old man, "but I’m sure everybody

kens the story. However, if ye’re no perfectly acquaint wi’ it, I’m sure

I’m willing to let ye hear it wi’ great pleasure; and a remarkable story

it is—and just as true, sir, ye may tak my word on’t, as that I’m raising

this bottle to my lips."

So saying, the old man

raised the flask to his mouth, and after a regular fisher’s draught,

added—

"Weel, sir, I’ll let ye

hear the story about Lord Soulis—You have, no doubt, heard of Hermitage

Castle, which stands upon the river of that name, at no great distance

from Hawick. In the days of the great and good King Robert the Bruce, that

castle was inhabited by Lord Soulis. [He was also proprietor of Eccles in

Berwickshire, and, according to history, was seized in the town of

Berwick—but tradition sayeth otherwise.] He was a man whose very name

spread terror far and wide; for he was a tyrant and a sorcerer. He had a

giant’s strength, an evil eye [There is, perhaps, no superstition more

widely diffused than the belief in the fascination of an evil eye or a

malignant glance; and I am sorry to say, the absurdity has still its

believers.] and a demon’s heart; and he kept his familiar

[Each sorcerer was supposed to have his familiar spirit, that

accompanied him; but Soulis was said to keep his locked in a chest.]

locked in a chest. Peer and peasant became pale at the name of Lord

Soulis. His hand smote down the strong, his eye blasted the healthy. He

oppressed the Poor, and he robbed the rich. He ruled over his vassals with

a rod of iron. From the banks of the Tweed, the Teviot, and the Jed, with

their tributaries, to beyond the Lothians, an incessant cry was raised

against him to Heaven and to the king. But his life was protected by a

charm, and mortal weapons could not prevail against him. (The seriousness

with which the narrator said this, shewed that he gave full credit to the

tradition, and believed in Lord Soulis as a sorcerer.)

He was a man of great

stature, and his person was exceeding powerful. He had also royal blood in

his veins, and laid claim to the crown of Scotland in opposition to the

Bruce. But two things troubled him; and the one was, to place the crown of

Scotland on his head—the other, to possess the hand of a fair and rich

maiden, named Marion, who was about to wed with Walter, the young heir of

Branxholm, the stoutest and the boldest youth on all the wide Borders.

Soulis was a man who was not only of a cruel heart, but it was filled with

forbidden thoughts; and, to accomplish his purposes, he went down into the

dungeon of his castle, in the dead of night, that no man might see him

perform the ‘deed without a name.’ He carried a small lamp in his hand,

which threw around a lurid light, like a glow-worm in a sepulchre; and, as

he went, he locked the doors behind him. He carried a cat in his arms.

Behind him a dog followed timidly, and before him into the dungeon he

drove a young bull that had ‘never nipped the grass.’ He entered the deep

and the gloomy vault, and, with a loud voice, he exclaimed—

‘Spirit of darkness!—I

come!’

He placed the feeble lamp

upon the ground in the middle of the vault; and, with a pick-axe, which he

had previously prepared, he dug a pit and buried the cat alive; and, as

the poor, suffocating creature mewed, he exclaimed the louder—

‘Spirit of darkness, come!’

He then leaped upon the

grave of the living animal and seizing the dog by the neck, he dashed it

violently against the wall, towards the left corner where he stood, and,

unable to rise, it lay howling long and piteously on the floor. Then did

he plunge his knife into the throat of the young bull, and, while its

bleatings mingled with the howling of the dying dog, amidst what might be

called the blue darkness of the vault, he received the blood in the palms

of his hands, and he stalked around the dungeon, sprinkling it in circles,

and crying with a loud voice—‘Spirit of darkness, hear me!’

Again he digged a pit, and

seizing the dying animal, he hurled it into the grave, feet upwards;

[These are the recorded practices which sorcerers resorted to when they

wished to have a glimpse of invisible spirits.] again he

groaned, and while the sweat stood on his brow—‘Come, spirit!—come!’

He took a horse-shoe, which

had lain in the vault for years, and which was called, in the family, the

spirit’s shoe, and he nailed it against the door, so that it hung

obliquely; [In the account of the trial of Elizabeth Bathgate, wife of

Alexander Pae, maltman in Eyemouth, one of the accusations in the dictment

against her was, that she had "ane horse-schoe in ane darnet and secriet

pairt of your dur, keepit by you thairopoun, as ane devilish meanis and

instructions from the devil." But the superstitions of the Borders, which

it is necessary to illustrate in these Tales, as exemplifying the

character of our forefathers, will be more particularly dwelt upon, and

their absurdity unmasked, in Tales which will shortly appear,

entitled—"Betty Bathgate, the Witch of Eyemouth;" "Peggy Stoddart, the

Witch of Edlingham;" and "The Laidley Worm of Spindlestone Heugh."]

and, as he gave the last blow to the nail, again he cried—

‘Spirit, I obey

thee!—come!’

Afterwards, he took his

place in the middle of the floor and nine times he scattered around him a

handful of salt, at each time exclaiming—

‘Spirit, arise!’

Then did he strike thrice

nine times with his hand upon a chest which stood in the middle of the

floor, and by its foot was the pale lamp, and at each blow he cried—

‘Arise, spirit! arise!’

Therefore, when he had done

these things, and cried twenty and seven times, the lid of the chest began

to move and a fearful figure, with a red cap [Red-cap is a name given to

spirits supposed to haunt castles.]upon its head, and which resembled

nothing in heaven above, or on earth below, rose and with a hollow voice,

inquired—

‘What want ye, Soulis?’

‘Power spirit!—power!’ he

cried, ‘that mine eyes may have their desire, and that every weapon formed

by man may fall scaithless on my body, as the spent light of a waning

moon!’

‘Thy wish is granted, mortal!’

groaned the fiend. [In the proceedings regarding Sir George Maxwell, it is

gravely set forth, that the voice of evil spirits is "rough and goustie;"

and, to crown all, Lilly, in his "Life and Times," informs us, that they

speak Erse—and, adds he, "When they do so, it’s like Irishmen, much in the

throat!"]‘Tomorrow eve, young Branxholm’s bride shall sit within thy

bower, and his sword return bent from thy bosom, as though he had dashed

it against a rock. Farewell! invoke me not again for seven years, nor open

the door of the vault; but then knock thrice upon the chest and I will

answer thee. Away! follow thy course of sin and prosper—but

beware of a coming wood.’

With a loud and sudden

noise, the lid of the massy chest fell, and the spirit disappeared, and

from the floor of the vault issued a deep sound, like the echoing of

thunder. Soulis took up the flickering lamp, and leaving the dying dog

still howling in the corner whence he had driven it, he locked the iron

door, and placed the huge key in his bosom.

In the morning, his vassals

came to him, and they prayed him on their bended knees, that he would

lessen the weight of their hard bondage; but he laughed at their prayers

and answered them with stripes. He oppressed the widow, and persecuted the

fatherless; he defied the powerful, and trampled on the weak. His name

spread terror wheresoever it was breathed, and there was not in all

Scotland a man more feared than the wizard Soulis, the Lord of Hermitage.

He rode forth in the

morning with twenty of his chosen men behind him, and wheresoever they

passed the castle or the cottage where the occupier was the enemy of

Soulis or denied his right to the crown, [If legitimacy could have

been proved on the part of the grandmother of Lord Soulis, he certainly

was a nearer heir to the crown than either Bruce or Baliol.]

they fired the latter, destroyed the cattle around the former, or he

sprinkled upon them the dust of a dead man’s hand, that a murrain might

come amongst them.

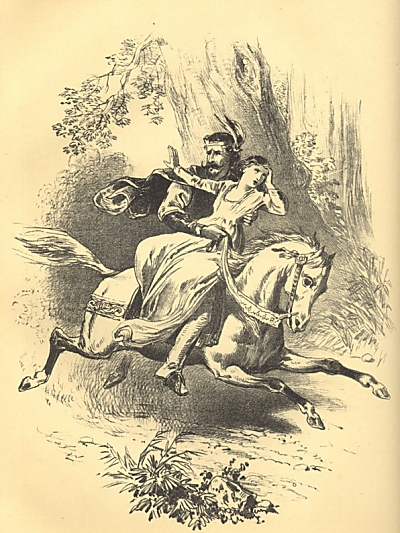

But as they rode by the

side of the Teviot he beheld fair Marion, the betrothed bride of young

Walter, the heir of Branxholm, riding forth with her maidens, and pursuing

the red deer. ‘By this token, spirit,’ muttered Soulis, joyously, ‘thou

has not lied—to-night young Branxholm’s bride shall sit within my bower.’

He dashed the spur into the

side of his fleet steed, and, although Marion and her attendants forsook

the chase and fled, as they perceived him, yet, as though his familiar

gave speed to his horse’s feet, in a few seconds he rode by the side

of Marion, and, throwing out his arm, he lifted her from the saddle while

her horse yet flew at its fastest speed, and continued its course without

its fair rider.

She screamed aloud, she

struggled wildly, but her attendants had fled afar off, and her strength

was feeble as an insect’s web in his terrible embrace. He held her upon

the saddle before him—

‘Marion!—fair Marion!’ said

the wizard and ruffian lover, ‘scream not—struggle not—be calm, and hear

me. I love thee, pretty one!—I love thee!’ and he rudely raised her lips

to his. ‘Fate hath decreed thou shalt be mine, Marion—and no human power

shall take thee from me. Weep not—strive not. Hear ye not, I love

thee—love thee fiercely, madly, maiden, as a she-wolf doth its cubs. As a

river seeketh the sea, so have I sought thee, Marion; and now thou art

mine— fate hath given thee unto me, and thy fair cheek shall rest upon a

manlier bosom than that of Branxholm’s beardless heir. Thus saying, and

still grasping her before him, he again plunged his spurs into the horse’s

sides and he and his followers rode furiously towards Hermitage Castle.

He locked the gentle Marion

within a strong chamber—he

‘Wooed her as a lion wooes

his bride.’

And

now she wept, she wrung her hands, she tore her raven hair before him, and

it hung dishevelled over her face and upon her shoulders. She implored him

to save her, to restore her to liberty; and again finding her tears wasted

and her prayers in vain, she defied him, she invoked the vengeance of

Heaven upon his head; and at such moments, the tyrant and the reputed

sorcerer stood awed and stricken in her presence. For there is something

in the majesty of virtue, and the holiness of innocence, as they flash

from the eyes of an injured woman, which deprives guilt of its strength,

and defeats its purpose, as though Heaven lent its electricity to defend

the weak.

And

now she wept, she wrung her hands, she tore her raven hair before him, and

it hung dishevelled over her face and upon her shoulders. She implored him

to save her, to restore her to liberty; and again finding her tears wasted

and her prayers in vain, she defied him, she invoked the vengeance of

Heaven upon his head; and at such moments, the tyrant and the reputed

sorcerer stood awed and stricken in her presence. For there is something

in the majesty of virtue, and the holiness of innocence, as they flash

from the eyes of an injured woman, which deprives guilt of its strength,

and defeats its purpose, as though Heaven lent its electricity to defend

the weak.

But, wearied with

importunity, and finding his threats of no effect, the third night that

she had been within his castle he clutched her in his arms, and, while his

vassals slept, he bore her to the haunted dungeon, that the spirit might

throw its spell over her and compel her to love him. He unlocked the massy

door. The faint howls of the dog were still heard from the corner of the

vault. He placed the lamp uponthe ground. He still held the gentle Marion

to his side, and her terror had almost mastered her struggles. He struck

his clenched hand upon the huge chest—he cried aloud— ‘Spirit! come

forth!’

Thrice he repeated the

blow—thrice be uttered aloud his invocation. But the spirit arose not at

his summons. Marion knew the tale of his sorcery—she knew and believed

it—and terror deprived her of consciousness. On recovering, she found

herself again in the strong chamber where she had been confined, but

Soulis was not with her. She strove to calm her fears, she knelt down and

told her beads, and she begged that her Walter might be sent to her

deliverance.

It was scarce daybreak when

the young heir of Branxholm, whose bow no man could bend, and whose sword

was terrible in battle, with twice ten armed men arrived before Hermitage

Castle, and demanded to speak with Lord Soulis. The warder blew his horn,

and Soulis and his attendants came forth and looked over the battlement.

‘What want ye boy,’

inquired the wizard chief, ‘that ere the sun be risen, ye come to seek the

lion in his den?’

‘I come,’ replied young

Walter, boldly, ‘in the name of our good king, and by his authority, to

demand that ye give into my hands, safe and sound, my betrothed bride,

lest vengeance come upon thee.’

"Vengeance! beardling!’

rejoined the sorcerer; ‘who dares speak of vengeance on the house of

Soulis?—or whom call ye king? The crown is mine—thy bride is mine, and

thou also shall be mine; and a dog’s death shalt thou die for thy

morning’s boasting.’

‘To arms!’ he exclaimed, as

he disappeared from the battlement, and within a few minutes a hundred men

rushed from the gate.

Sir Walter’s little band

quailed as they beheld the superior force of their enemies, and they were

in dread also of the sorcery of Soulis. But hope revived within them when

they beheld the look of confidence on the countenance of their young

leader, and thought of the strength of his arm, and the terror which his

sword spread.

As hungry tigers spring

upon their prey, so rushed Soulis and his vassals upon Sir Walter and his

followers. No man could stand before the sword of the sorcerer.

Antagonists fell as impotent things before his giant strength. Even Walter

marvelled at the havoc he made, and he pressed forward to measure swords

with him. But, ere he could reach him, his few followers who had escaped

the hand of Soulis and his host, fled and left him to maintain the battle

singlehanded. Every vassal of the sorcerer, save three, pursued them; and

against these three, and their charmed lord young Walter was left to

maintain the unequal strife. But, as they pressed around him, ‘Back!’

cried Soulis, trusting to his strength and to his charm; ‘from my hand

alone must Branxholm’s young boaster meet his doom. It is meet that I

should give his head as a toy to my bride, fair Marion.’

‘Thy bride, fiend!’

exclaimed Sir Walter; ‘thine!—now perish!’ and he attacked him furiously.

‘Ha! ha!’ cried Soulis, and

laughed at the impetuosity of his antagonist, while he parried his

thrusts; ‘take rushes for thy weapon, boy; steel falls feckless upon me.’

‘Vile sorcerer!’ continued

Walter, pressing upon him more fiercely; ‘this sword shall sever thy

enchantment.’

Again Soulis laughed, but

he found that his contempt availed him not, for the strength of his enemy

was equal to his own, and in repelling his fierce assaults, he almost

forgot the charm which rendered his body invulnerable. They fought long

and desperately, when one of the followers of Soulis, suddenly and

unobserved, thrusting his spear into the side of Sir Walter’s horse, it

reared, stumbled, and fell, and brought him to the ground.

‘An arrow-schot!’ [When

cattle died suddenly, it was believed to be by an arrow-schot—that is shot

or struck down by the invinsible dart of a sorcerer.] exclaimed Soulis;

‘wherefore, boy, didst thou presume to contend with me?’ And suddenly

springing from his horse, he pressed his iron heel upon the breast of his

foe, and turning also the point of his sword towards his throat—

‘Thou shalt not die yet,’

said he; and turning to the three attendants who had not followed in the

pursuit, he added— ‘Hither—bind him fast and sure.’ Then did the three

hold him on the ground, and bind his hands and his feet, while Soulis held

his naked sword over him.

‘Coward and wizard!’

exclaimed Walter, as they dragged him ‘within the gate, ye shall rue this

foul treachery.’

‘Ha! ha! vain, boasting

boy!’ returned Soulis, ‘thou indeed shalt rue thy recklessness.’

He caused his vassals to

bear Walter into the strong chamber where fair Marion was confined, and,

grasping him by the neck, while he held his sword to his breast, he

dragged him towards her, and said sternly—’ Consent thee, now, maiden, to

be mine, and this boy shall live,—refuse, and his head shall roll before

thee on the floor as a plaything.’

‘Monster!’ she exclaimed,

and screamed aloud; ‘would ye harm my Walter?’

‘Ha! my Marion!—Marion!’

cried Walter, struggling to be free. And, turning his eyes fiercely upon

Soulis, ‘Destroy me, fiend,’ he added, ‘but harm not her.’

‘Think on it, maiden,’

cried the sorcerer, raising his sword; ‘the life of thy bonny bridegroom

hangs upon thy word. But ye shall have until midnight to reflect on it. Be

mine, then, and harm shall not come upon him or thee; But a man shall be

thy husband, and not the boy whom he hath brought to thee in bonds.’

‘Beshrew thee, vile

sorcerer!’ rejoined Walter, ‘were my hands unbound, and unarmed as I am, I

would force my way from the prison, in spite of thee and thine!’

Soulis laughed scornfully,

and again added—‘Think on it, fair Marion.’

Then did he drag her

betrothed bridegroom to a corner of the chamber, and ordering a strong

chain to be brought, he fettered him against the wall; in the same manner,

he fastened her to the opposite side of the apartment; but the chains with

which he bound her were made of silver.

‘When they were left alone,

‘Mourn not, sweet Marion,’ said Walter, ‘and think not of saving me—before

to-morrow our friends will be here to thy rescue; and, though I fall a

victim to the vengeance of the sorcerer, still let me be the bridegroom of

thy memory.’ Marion wept bitterly, and said that she would die with him.

Throughout the day, the

spirit of Lord Soulis was troubled, and the fear of coming evil sat heavy

on his heart. He wandered to and fro on the battlements of his castle,

anxiously looking for the reproach of his retainers, who had followed in

pursuit of the followers of Branxholm’s heir. But the sun set, and the

twilight drew on, and still they came not; and it was drawing towards

midnight when a solitary horseman spurred his jaded steed towards the

castle gate. Soulis admitted him with his own hand into the court-yard;

and, ere the rider had dismounted, he inquired of him, hastily, and in a

tone of apprehension—

‘Where be thy fellows,

knave? and why come alone?’

‘Pardon me, my lord,’ said

the horseman, falteringly, as he dismounted; ‘thy faithful bondsman is the

bearer of evil tidings.’

‘Evil slave!’ exclaimed

Soulis, striking him as he spoke ‘speak ye of evil to me? What of

it?—where are thy fellows?’

The man trembled, and

added—‘In pursuing the followers of Branxholm, they sought refuge in the

wilds of Tarra, and being ignorant of the winding paths through its

bottomless morass, horses and men have been buried in it—they who sank not

fell beneath the swords of those they had pursued, and I only have

escaped.’

‘And wherefore did ye

escape, knave?’ cried the fierce sorcerer—‘why did ye live to remind me of

the shame of the house of Soulis?’ And, as he spoke, he struck the

trembling man again.

He hurried to the haunted

dungeon, and again performed his incantations, with impatience in his

manner and fury in his looks. Thrice he violently struck the chest, and

thrice he exclaimed, impetuously—

‘Spirit! come forth!—arise

and speak with me?’

The lid was lifted up, and

a deep and angry voice said— ‘Mortal! wherefore hast thou summoned me

before the time I commanded thee? Was not thy wish granted? Steel shall

not wound thee—cords bind thee—hemp hang thee— nor water drown thee.

Away!’

‘Stay!’ exclaimed Soulis—‘add

nor fire consume me?’

‘Ha! ha!’ cried the spirit,

in a fit of horrid laughter that made even the sorcerer tremble—‘Beware

of a coming wood!’ And, with a loud clang, the lid of the chest fell,

and the noise as of thunder beneath his feet was repeated.

‘Beware of a coming wood!’

muttered Soulis to himself, ‘what means the fiend?’

He hastened from the

dungeon without locking the door behind him, and, as he hurried from it,

he drew the key from his bosom, and flung it over his left shoulder,

crying, ‘keep it, spirit!’

He shut himself up in his

chamber to ponder on the words of his familiar, and on the extirpation of

his followers; and he thought not of Marion and her bridegroom until

daybreak, when, with a troubled and a wrathful countenance, he entered the

apartment where they were fettered.

‘How now, fair maiden?’ he

began; ‘hast thou considered well my words?—wilt thou be my willing bride,

and let young Branxholm live? or refuse, and look thy fill on his smooth

face, as his head adorns the point of my good spear?’

‘Rather than see her thine,’

exclaimed, Walter, ‘I would thou shouldst hew me in pieces, and fling my

mangled body to your hounds.’

‘Troth ! and ‘tis no bad

thought,’ said the sorcerer; ‘thou mayest have thy wish. Yet, boy, ye

think that I have no mercy? will teach thee that I have, and refined mercy

too. Now, tell me truly were I in thy power as thou art in mine, what fate

would ye award to Soulis?’

‘Then, truly,’ replied

Walter, ‘I would hang thee on the highest tree in Branxholm woods.’

‘Well spoken, young

Strong-bow,’ returned Soulis; ‘and I will shew thee, though ye think I

have no mercy, that I am more merciful than thou. Ye would choose for me

the highest tree, but I shall give thee the choice of the tree from

which you may prefer your body to hang, and from whose top the owl may

sing its midnight song, and to which the ravens shall gather for a feast.

And thou, pretty face,’ added he, turning to Marion, ‘sith you will not,

even to save him, give me thine hand, i’ faith if I may not be thy

husband, I will be thy priest and celebrate your marriage, for I will bind

your hands together and ye shall hang on the next branch to him.’

‘For that I thank thee,’

said the undaunted maiden.

He then called together his

four remaining armed men, and placing halters round the necks of his

intended victims, they were dragged forth to the woods around the

Hermitage, where Walter was to choose the fatal tree.

Now a deep mist covered the

face of the earth, and they could perceive no object at the distance of

half a bow-shot before them; and, ere he had approached the wood where he

was to carry his merciless project into execution—

‘The wood comes towards

us!’ exclaimed one of his followers.

‘What!—the wood comes!’

cried Soulis, and his cheek became pale, and he thought on the words

of the demon--‘Beware of a coming wood!’ —and, for a time, their

remembrance, and the forest that seemed to advance before him, deprived

his arm of strength, and his mind of resolution, and, before his heart

recovered, the followers of the house of Branxholm to the number of

fourscore, each bearing a tall branch of a rowan tree in their hands, [It

is probable that the legend of the ‘coming wood’ referred to in

tradition respecting Lord Soulis, is the same as that from which

Shakspeare takes Macbeth’s charm—"Till Birnam wood shall come to Dunsinane."

The circumstances are similar.] as a charm against his sorcery, perceived,

and, raising a loud shout surrounded him.

The cords with which the

arms of Marion and Walter were bound were instantly cut assunder. But,

although the odds against him were as twenty to one, the daring Soulis

defied them all. Yea, when his followers were overpowered, his single arm

dealt death around. Now, there was not a day that passed that complaints

were not brought to King Robert, from those residing on the Borders,

against Lord Soulis, for his lawless oppression, his cruelty, and his

wizard-craft. And, one day there came before the monarch, one after

another, some complaining that he had brought diseases on their cattle, or

destroyed their houses by fire, and a third that he had stolen away the

fair bride of Branxholm’s heir; and they stood before the King and begged

to know what should be done unto him. Now the King, was wearied with their

importunities and complaints, and he exclaimed, peevishly and

unthinkingly—‘Boil him, if you please, but let me hear no more

about him.’ But,

—‘it is the curse of kings to be

attended

By slaves that take their humour for

a warrant;’

and when the enemies of

Soulis heard these words from the lips of the King, they hastened away to

put them in execution; and with them they took a wise man, one who was

learned in breaking the spells of sorcery, [Dr. Leyden represents this

personage as being "True Thomas, Lord of Ersylton;" but the Rhymer was

dead before the time fixed by tradition of the death of Lord Soulis, which

took place in the reign of Robert the Bruce, who came to the crown in

1308, and the Rhymer was dead before 1299, for, in that year, his son and

heir granted a charter to the convent of Soltra, and in it he describes

himself Filius et hares Thomas Rymour de Erceldon.] and with him he

carried a scroll, on which was written the secret wisdom of Michael the

Wizard; and they arrived before Hermitage Castle, while its lord was

contending single-handed against the retainers of Branxholm, and their

swords were blunted on his buckler, and his body received no wounds. They

struck him to the ground with their lances; and they endeavoured to bind

his hands and his feet with cords, but his spell snapped them asunder as

threads.

‘Wrap him in lead,’ cried

the wise man, ‘and boil him therewith, according to the command of the

king; for water and hempen cords have no power over his sorcery.’

Many ran towards the

castle, and they tore the lead from the turrets, and they held down the

sorcerer, and rolled the sheets around him in many folds, till he was

powerless as a child, and the foarn fell from his lips in the impotency of

his rage. Others procured a caldron, in which it was said many of his

incantations were performed, and the cry was raised,--

‘Boil him on the Nine-stane

rig!’

And they bore him to where

the stones of the Druids are to be seen till this day, and the two stones

are yet pointed out from which the caldron was suspended. They kindled

piles of faggots beneath it, and they bent the living body of Soulis

within the lead, and thrust it into the caldron; and, as the flames arose,

the flesh and the bones of the wizard were consumed in the boiling

lead.--Such was the doom of Soulis.

The King sent messengers to

prevent his hasty words being carried into execution, but they arrived too

late.

In a few weeks there was

mirth and music, and a marriage feast in the bowers of Branxholm, and fair

Marion was the bride."