|

"That’s a bit bonnie

beastie, callant," said Walter Greenlaw, approaching a country lad, who

was carrying a cock under his arm, and proceeding with it towards the

village of Greystone; Walter being himself at the moment employed in

taking his morning saunter on the Dumfries road, a recreation in which he

always indulged in the summer time previous to opening his shop—a

well-filled and thriving one, in the village above named. "That’s a bit bonnie

beastie, callant," said Walter Greenlaw, approaching a country lad, who

was carrying a cock under his arm, and proceeding with it towards the

village of Greystone; Walter being himself at the moment employed in

taking his morning saunter on the Dumfries road, a recreation in which he

always indulged in the summer time previous to opening his shop—a

well-filled and thriving one, in the village above named.

Walter was in the grocery

and spirit-dealing line, in which line he had done well. He was easy—easy

in temper and circumstances; but, with regard to the former, just a trifle

obstinate or so. Walter, in fact, notwithstanding his other good

qualities, was as positive as a mule, and would never give in, when he

once took a notion that he was right—and he did this in ninty-nine

cases out of every hundred.

"A bit bonny beastie that,

callant," said Walter Greenlaw, stopping the lad, and beginning to examine

the bird’s feet, spurs, comb, and other personal qualifications—for Walter

was a bit of a connoisseur in such matters. He was a great cock fancier,

and, though in other respects a sedate, regular, and humane sort of man,

entertained something like a prediliction for cock-fighting. It was, in

truth, rather a hobby of his; and was the only sort of pastime, if a thing

so cruel can be called by that name, in which he indulged.

"Are ye gaun to sell him,

laddie?" now inquired Walter who found the cock a bird of promise.

"I dinna ken, sir," replied

the boy, stratching his head. "What wad ye gie’s for him?"

"What wad ye be seekin?"

rejoined Walter/

The boy thought a moment;

"He’s weel wordy o’ twa shillings," he at length said.

"I’ll gie ye aughteenpence,"

replied Walter, who was a dead hand at a bargain.

"Hae, tak him, then," said

the boy, holding out the bird to the purchaser. Walter plunged his hand

into his pocket, drew out one shilling and sixpence sterling money of this

realm, put it into the boy’s hand, took the cock under his arm, and

retraced his steps homewards with his prize.

Ah, little did Walter know

what mischief that unhappy cock was to breed him. Little did the

unsuspecting man dream, that, in carrying it home, as he was now doing

rejoicingly, he was carrying home ruin and distraction of mind. Who would

have thought it more than Walter?! Who would have thought that a thing so

apparently simple should contain within it the germs of great events? Yet,

so it was; and it adds another to the many instances already extant, of

mighty endings proceeding from small beginnings. We need not add, we

suppose, that if Walter had known to what that morning’s work was to lead,

he would as soon have taken a dose of prussic acid, as have bought the

unlucky cock, of which he was now, in his ignorance, so vain.

Having brought his cock

home, Walter carried him straight into his back shop, where it was his

intention to keep him for a few days, that he might have him always under

his immediate eye, and be thus enabled to bestow upon him all the due

attention, without absenting himself for an instant from the duties of his

shop. He was thus situated, too, in the most convenient place for

undergoing such processes of training as might be deemed desirable.

For several days,

everything went on well with Walter and the cock: the former discovering

every day new points of excellence in the bird, and the latter every day

exhibiting new and promising traits of character, and being apparently

perfectly satisfied with his quarters. The cock and Walter were,

therefore, on the best of terms with each other, and so they continued for

about the time above-mentioned. At the end of this period, however, an

unlucky circumstance occurred to disturb the pleasing harmony.

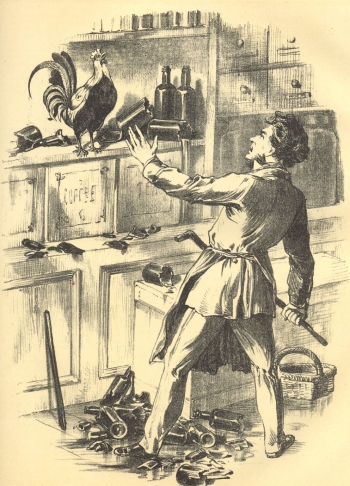

One day, while Walter was

standing at his shop door looking listlessly around him, for lack of

customers, he was suddenly startled by hearing a crash on the floor, first

of one bottle, and then of another bottle, and then of a third and a

fourth, in rapid succession, and, lastly, of a whole shower of them. The

ruinous sounds proceeded from the back shop, where the cock was. Walter

knew it, and rushed into the apartment; and when he did so, what a seen

presented itself to his eyes. The floor was swimming six inches deep in

his best strong ale, and was covered with the fragments of the bottles

which had once contained it. Walter cast his eyes up to the shelf on which

the ale formerly stood, to the amount of some twelve or fifteen dozen and,

to his unspeakable horror, found the cock boldly planted right in the

middle of those that remained. Walter looked at the cock in silence for a

instant; for he dare not make the slightest motion towards displacing him,

as such attempt would only have insured the entire demolition of what

bottles remained.

He, therefore, as we said,

looked in silence and for some time on the ruthless destroyer of his

property. Walter’s look was one of unmitigated wrath. The cock returned it

with one of bold defiance; chuckling and gluggering angrily the while, as

if to say that, if his conduct was any way resented he would do yet ten

times more mischief. He seemed, in truth, perfectly conscious that

he had still several dozens of ale at his entire disposal, and that a few

more flaps of his wings was all that was necessary to send them down

amongst the rest. Walter perfectly knew this too, and by his caution

acknowledged himself to be completely in the power of the mischievous

bird. Fore some time, then the two looked at each other without making the

slightest motion—Walter thinking of how he should proceed, and the cock

evidently waiting to see what that proceeding should be, as if, whatever

it was, he should thereby regulate his own conduct.

This, however, was a state

of matters which could not be allowed to continue. The cock must be

displaced—Walter both felt and saw that he must; and he finally resolved

on attempting it. Approaching him cautiously, and with coaxing and

wheedling air, he aimed at closing with him but it wouldn’t do. The cock

wasn’t to be so taken in. The moment he saw Walter advancing upon

him, he bridled up, gluggered fiercely, retreated into a thicket of

bottles, and canted over another half-dozen in the operation. Rendered

desperate by this continued destruction of his property, Walter, now

losing all temper and prudence, seized a stick that lay at hand, and,

regardless of consequences rushed upon the destroyer, and, by his bold and

decisive measure, cleared the shelf at once of the cock and of almost

every remaining bottle that was on it. And thus ended the first exploit of

Walter’s new acquisition in the feathered line. The destruction was

horrible; but there was no help for it—no remedy. To revenge it on the

cock, was out of the question; so that all that befell him in consequence,

was his removal to an out-house, where it was determined he in future

should remain.

We have already said that

cock-fighting was one of Walter Greenlaw’s hobbies. It was so; and there

were two or three persons in the village, and in the country around, who

were addicted to the pastime also. These persons, and Walter along with

them, used frequently to meet for the purpose of enjoying their favourite

recreation, the scene of which was a certain barn in the neighbourhood;

and, on these occasions, bets went frequently pretty high amongst them.

To these lovers of the

main, it was soon known that their friend Mr. Greenlaw had laid his hands

upon a choice bird, game every inch of it, including the feathers; and

much anxiety was expressed amongst them to see how he would conduct

himself in battle; and not a little vain of this anxiety was the happy

owner of the gallant bird, which was, in truth, a stately animal. His

spurs were like two heckle pins, long and sharp, and most murderous

looking; while his bold strut and lofty bearing shewed that he was worthy

of his weapons, by giving assurance of his being both able and willing to

make use of them.

Frequent, then, were the

calls of the different members of the cock-fighting fraternity of

Greystone on Mr. Green-law, to see his bird, and to admire his proportions

and combative capabilities—one and all declaring that he was a perfect

paragon, a nonpareil, on which any sum might be safely staked. Walter

thought so too, and felt rather anxious that some one would take him up.

He would at once have gone a five pound note upon him; taking care,

however, that his wife knew nothing about it.

At length, however, the

desired event came round. Another of the fraternity, a farmer, lighted

upon a cock, which both he and some of the others of the corps thought

superior to Mr. Greenlaw’s; and the consequence was, a wager to the extent

not of five but of ten pounds, so convinced was each of the merits of

their respective cocks. A day of trial was appointed; the barn, the usual

scene of the exhibitions, was the placed fixed on. The parties and their

friends met. The cocks were pitted against each other, and a deadly combat

ensued. For a time Mr. Greenlaw’s cock fully maintained the character

attributed to him, and shewed such a decided superiority over his

antagonist, both in severity of stroke and quickness of eye, that his

owner, in the enthusiasm of the moment, doubled his bet, and made it

twenty pounds instead of ten. In the meantime, the battle raged with

unabated ardour; victory hovering with doubtful wing between the

combatants. At this interesting crisis, Walter, not seeing any doubt at

all in the matter, felt as sure of his neighbour’s twenty pounds as if he

already had them in his breeches pocket. What, then, was his amazement,

what his mortification, when he saw his redoubted cock all at once sport

the white feather! He could scarcely believe his own eyes; but it was a

fact, a melancholy fact. Walter’s cock all at once drooped tail, and

sought safety in disgraceful flight. The victorious cock gave chase, and

pecked the fugitive round the ring. After this exhibition, there could be

no doubt how the wagers were to go; and a nudge on the elbow from the

winner awakened Mr. Greenlaw to a sense of his particular position as

regarded this matter. Mr. Greenlaw took the hint, and, with slow hand and

heavy heart, counted over his stake in good bank notes to the owner of the

victorious bird. Shortly after this, Mr. Greenlaw took his battered and

crestfallen cock under his arm, and, nearly as crest-fallen himself,

commenced his march homewards; and as he did so— that is, while he walked

home—he bestowed a good deal of thought on the general conduct of his

cock; took a retrospective review, as it were, of his behaviour; and the

result was an impression that he had got rather an unlucky sort of animal;

for the debit of his account was swelling rapidly up, while there was not

a single item at his credit. At this debit, there was his first cost,

eighteenpence; then there was his keep, and the trouble therewith; then

there was nearly a gross of Younger’s best ale, bottles and all; then, and

lastly—that is, so far as matters had yet gone— there were twenty pounds

sterling money lost, gone forever, through the cowardly spirit of the

craven bird. All this was bad enough; but Walter still hoped matters might

mend, and that the cock, by a little more judicious training, might be

brought to refund in some shape or other; and, under this impression,

Walter again took him in hand, and began a course of feeding, together

with a series of other proceedings, all secundum artem, which he

trusted would end in leading himself to cash, and his cock to glory.

At this stage of the

history of Walter Greenlaw and his cock, we find it necessary to introduce

another person on the stage; and this person is little Jamie Greenlaw, the

son and heir of Walter—a wild, young scamp, and as fond of cock-fighting

as his father. Now, this little rogue had long secretly desired to see a

battle between his father’s cock and the schoolmaster’s, but had never

been able to bring about the desirable event. At length, however, he

accomplished it. He got up one morning very early, before any one was

stirring; stole away his father’s cock; carried him straight to the

schoolmaster’s; scaled the wall of his back yard; and, in a minute after,

had the satisfaction of seeing the two cocks engaged in mortal strife. It

was a joust a’ outrance. Now, it happened, through that

perversity which sometimes mark circumstances as well as conduct, that

Walter Greenlaw’s cock, on this occasion, fought nobly—that is, he fought

well when it was of no consequence whether he did so or not. Yes, he

fought well; so well that, in less than five minutes, he laid the

schoolmaster’s cock dead at his feet. This being a much more serious

result than Jamie had anticipated, Jamie, in great alarm and perturbation,

seized his own cock, placed him under his arm, and commenced a hurried

retreat. This retreat, however, he did not effect without being seen.

Standing in his shirt and red Kilmarnock nightcap, at a back window, the

schoolmaster saw him; saw Jamie with his father’s cock under his arm, and

saw his own lying dead in the yard beneath the window—circumstances which

at once conducted him to a knowledge of the facts of the case. On that

very day, that fatal day, Walter Greenlaw received a written demand from

the schoolmaster for the value of his cock; which value the said demand

set forth to be three shillings and sixpence sterling money. Now, Walter

demurred, nay, absolutely refused to pay, alleging that the schoolmaster’s

cock had fallen in fair fight. The schoolmaster insisted. Walter held out.

The schoolmaster summoned. Walter appeared and stated his case; but

judgment went against him. The schoolmaster was found, under all the

circumstances of the case, entitled to the value of his cock, and Walter

was therefore decerned against in the full amount, with expenses.

Now, at this point in the

affair, or, perhaps, a little before, the very marked quality of Walter’s

nature, formerly hinted at, came into play—namely, his obstinacy. Walter

protested against the decision now given against him, and brought his case

under the revision of the Sheriff. It was again given against him, with

additional expenses, a circumstance this, however, which only tended to

convince Walter that he was right, and to confirm him in his

determination to keep the flag of defiance and resistance, which he had

hoisted, boldly flying; nay, he may be said to have now nailed it to the

mast. In less than a month after, Walter’s, or the gamecock case, was

before the Court of Session. It became a question of costs; the judgment

of the inferior courts was confirmed, and Walter was again cast, with the

addition of a tail of expenses as long as a comet’s. Never mind. "Do or

die," was Walter’s motto. He was still right, and they were all

wrong—magistrates, sheriffs, and judges; and Walter determined on shewing

them and the world that it was so. Walter carried his case into the House

of Peers— where, O shade of Justinian, it was again given against him.

Walter could do no more. He had done all that man could do to establish

the fact that he was right, and that everybody else was wrong. But there

was evidently a conspiracy against him. There was no justice to be had;

so, consoling himself with the idea that he was a martyr to an iniquitous

system of jurisprudence, Walter paid, with the best grace he could, the

last shilling of the law charges which he had incurred in the game-cock

case, and which amounted altogether, to several hundred pounds.

On this being done—"What,"

said Walter, with a very long and a very grave face, to his better half,

"what’ll we do noo wi’ the cursed brute?"—meaning the cock, which was at

the moment strutting and crowing before the window as boldly and

confidently as if he had never cost his owner a sixpence.

"What’ll ye do wi’ him,"

replied Mrs. Greenlaw, sharply, "but thraw his neck, the confounded

beast!"

"Feth, I believe ye’re

richt, gudwife," replied her husband, with a dismal smile.

The sentence of death thus

passed on the cock was forthwith put in execution; and, on the following

day, his mortal remains were served up at Walter’s table, along with a

tureen full of cocky-leekie.

"That’s guid-lookin cocky-leekie,

gudwife," said Mr. Greenlaw, as he stirred with his spoon a reaming plate

of the nutritious broth; "but nae better than it should be, considering

the cost o’t. Every spoonfu’ o’t cost me a pound note, if it cost a

farthin."

"Weel, I hope it’s cured ye

o’ cock-fechtin, Walter."

"As lang’s I leeve,"

replied he. And he kept his word. |