|

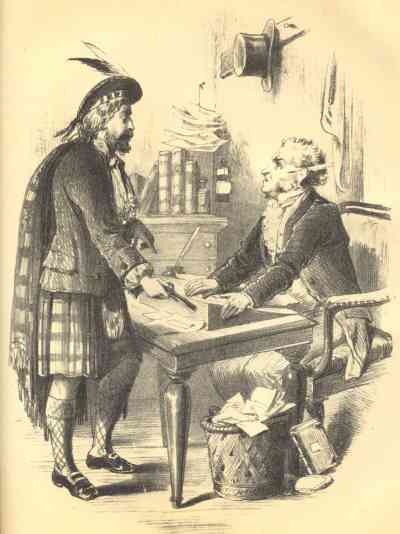

One day, in the summer of

the year 1752, a stranger of very remarkable appearance, entered a certain

banking office in the city of Glasgow. He was a man of immense stature, of

fierce aspect, and wore the full dress of a Highlander, of which country

his accent discovered him to be a native. One day, in the summer of

the year 1752, a stranger of very remarkable appearance, entered a certain

banking office in the city of Glasgow. He was a man of immense stature, of

fierce aspect, and wore the full dress of a Highlander, of which country

his accent discovered him to be a native.

In the manner in which the

stranger made his entre into the banking-office, there was a

curious mixture of boldness and timidity. In the first place, he opened

the door slowly and cautiously, almost as it were by stealth. This done,

he thrust in his head to reconnoitre before advancing a step further;

when, seeing only one person in the office, he assumed the haughty air

which seemed natural to him, stalked into the apartment, banged the door

after him with some violence, and then advanced with a firm step towards a

small desk—for banking-office establishments were then altogether on a

small scale—at which the banker himself, an elderly gentleman, was seated.

The latter, from the moment

the stranger had first thrust his head in at the door, had kept his eye

fixed on him with a look of inquiry, which, said, as plainly as if it had

been spoken, "Who, in the name of all that’s suspicious, art thou,

friend?" The stranger instantly perceived that he was looked upon with

more than ordinary interest, and he did not seem to relish the

distinction.

On approaching the banker,

who was still gazing upon him with a look of intense inquisitiveness and

curiosity, the stranger stood still; and to the inquiry of the former

regarding his business, made no other reply than by beginning to grope

under his plaid, as if in search of something concealed in its voluminous

folds, from which he at length drew a dirty scrap of paper. At this he

glanced for an instant himself, then threw it haughtily on the desk before

the banker. The latter lifted the singular looking document, adjusted his

spectacles, and proceeded to give it a deliberate perusal. This done, he

again laid it down, raised his glasses high on his forehead, with the air

of one who is about to commence a serious and important investigation into

singularly suspicious circumstances; and, addressing the stranger,

said—"Pray, friend, where got you this order?"

"Why, what does it signify

how or where I got it?" replied the former, gruffly. "It is all right, I

suppose, and I want the money for it."

"Right, oh! ay, right,"

said the banker, again lifting the paper, and looking at the signature for

at least the sixth time—"perhaps it is, but the whole matter is odd. This

gentleman," he added, pointing to the subscriber’s name, "left Glasgow

yesterday, to my certain knowledge, for the Highlands, and, previously to

his departure, we adjusted all matters between us, and of this order he

said nothing. In short, sir," he went on, "under all the circumstances of

the use, I decline paying you this money." And the old gentleman pressed

his lips together with an air of fixed resolution .

When he had done—

"So, so," replied the

bearer of the rejected draft, "you don’t like the order. It’s suspicious

you think." Here he turned suddenly round about, and threw a rapid glance

around the apartment, as if to be assured that there was no one present

but themselves. Then, again confronted the banker, "You don’t like the

order," he repeated, and, in the same instant, he plunged his hand beneath

his plaid. ‘Why, then, here’s another, a genuine one. What say you to

that draft, Mr Banker?" And he planted the muzzle of a pistol on the

edge of the little desk at which the person whom he addressed was seated.

"What, don’t you like this either?" he said jocosely, as if he enjoyed the

terror and alarm which was now strongly depicted on the countenance of the

banker. "But, come," he added, more sternly, "like it or not, down with

the money; I’ve no time to loose. Down with the money, or—" and he

completed the sentence by a significant motion of the imposing weapon

which he held in his hand.

"What, sir! what, sir!"

exclaimed the banker, leaping from his sent in the most dreadful

consternation and alarm, his lips pale and quivering with fright, "do you

mean to rob me?"

"Rob you," replied the

terrible stranger, coolly; "rob you—no, no; by no means. I only want you

to give me my own."

"I will call out for

assistance, sir; I will get you apprehended—I will get you hanged!"

exclaimed the banker, still dreadfully discomposed.

"You had better not,

replied the stranger, "else you may rue it." And he made another

significant motion with his pistol.

Perceiving now that it was

both idle and dangerous to tamper longer with his extraordinary visitor,

the banker opened a huge iron door in the wall of the apartment, close by

where he had been sitting, and proceeded to count out the amount of the

draft which he was thus forcibly compelled to honour.

"Now," said the stranger,

on putting the last handful of the coin which had been told down to him

into a large leathern purse with which he was provided, "that this little

matter is settled between us, I will tell you something that may be worth

your knowing. If you attempt to follow me one single step, or if you make

the slightest effort to have me pursued, you may rest assured of having

your house, one of these nights, burnt about your ears. If I escape any

such attempt as that I speak of, this I would do with my own hand. If I am

taken, there are certain friends of mine who will do it for me, and,

perhaps, blow your brains out to the bargain."

Having said this, the

strange; after bidding the banker good morning, stalked deliberately out

of the office, leaving the latter to his own reflections on what had just

taken place.

Fully confiding, as he had

good reason to do, in the threat which had been held out to him, he did

not attempt to follow his tremendous visitor; but stood gazing in rueful

silence, on his retiring figure as he left the office. There was another

reason, however, for the banker’s forbearance on this occasion. The draft

which he had paid, he felt assured, was genuine; he only doubted the

circumstances in which it had appeared, and was, therefore, secure from

pecuniary loss—a circumstance which had due weight with him, and which

effectually reconciled him to the escape of his customer.

And now, good reader, you

will be somewhat curious to know, we presume, whom this strange person

was. This curiosity we can easily gratify. He was the celebrated Highland

freebooter of the name of John Dhu Cameron, or Sergeant Mor, as he was

called in this native country, from his large stature. The order, whose

odd process of being cashed we have above described, was extorted from a

gentleman whom the sergeant met with in the Highlands; and who was

detained a prisoner by his gang, but treated with much hospitality, until

John Dhu’s return with the money, when he was liberated and escorted to a

place of safety. The proceeding of the sergeant, in the case just related,

was a bold one; for he was well known and ran great risk of being taken

and hanged. But fortune favours the brave; and John, as we have seen,

succeeded in bringing the dangerous transaction to a happy conclusion. |