|

A PASSAGE FROM THE HISTORY

OF THE REBELLION.

Many of the Maxwells of

Galloway were out in the forty five, and, after the disaster which put an

end to the Stuart cause for ever, few felt more severely the royal

displeasure than the catholics of the stewartry. The last of the Maxwells

of Orchardtown, in that district, having fought with desperate courage in

the ranks of the Pretender, was pursued by the king’s troops with the

sanguinary spirit of the blood-hounds. His activity and the knowledge of

the country afforded him, however, advantages which set for a long time at

defiance all the efforts of his pursuers; but the hardships he

encountered, and the privations he suffered, purchased, at a high price,

the short respite his ingenuity gained from a melancholy fate. Many of the Maxwells of

Galloway were out in the forty five, and, after the disaster which put an

end to the Stuart cause for ever, few felt more severely the royal

displeasure than the catholics of the stewartry. The last of the Maxwells

of Orchardtown, in that district, having fought with desperate courage in

the ranks of the Pretender, was pursued by the king’s troops with the

sanguinary spirit of the blood-hounds. His activity and the knowledge of

the country afforded him, however, advantages which set for a long time at

defiance all the efforts of his pursuers; but the hardships he

encountered, and the privations he suffered, purchased, at a high price,

the short respite his ingenuity gained from a melancholy fate.

Maxwell observed that his

companions in misfortune generally fled as far as possible from their

respective counties, conceiving that the investigations of the soldiers

would be directed, in the first instance, to the places of their abode.

This, it is well known, was a great error; for the seizures of the

fugitives that took place were much more frequently the consequence of the

unfriendly character of the persons who concealed them, and who had little

interest in their security, than any suspicions of the soldiers directed

to localities. Taking advantage of that error, Maxwell went direct to the

parish of Urr, where he knew there were many catholics who would lay down

their lives for his salvation.

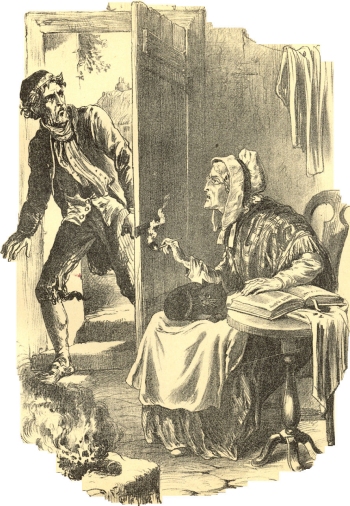

Clothed in the garb of a

common labourer, the proprietor of the large estates of Orchardtown

hastened his progress to the place of his hope. It was late at night when

he arrived at the little, but beautiful village of Dalbeatie situated on

the banks of the angry Urr. He was in a state of great exhaustion as well

as of solicitude—fear he knew not—for he had heard, at several periods,

behind him, the tread of horses, which his heated imagination at once

converted into those of troopers. Taking no time to select the dwelling of

a catholic, he ran up to the nearest door that presented itself; and,

lifting the latch, stood before an old woman, who sat at a clear crackling

fire, smoking a short cutty pipe, as black as the cat that sat on her

knee, and reading her Bible. There was nothing for it but to dash at once

into the question whether she was catholic or protestant.

"A very odd question that,

in these strange times," answered the old woman, "and ane I’m no inclined

to answer, till I am informed what use ye intend to mak o’t."

"I am a fugitive from the

king’s troops," said Maxwell, "and claim the protection of a christian,

whether of the one persuasion or the other."

"And that ye shall hae,"

answered the woman with briskness, "but only upon ae condition."

"What is that?" said

Maxwell.

"It is just that ye dinna

ask me to deny you," answered the old woman; "ye hae my house at your

command, everything in it that may assist ye in concealing frae Geordie’s

hounds, except my conscience."

At this moment, Maxwell

thought he heard the sound of the troopers, and taking advantage of the

qualified consent of the old woman, stept forward, with a view to explore

the recesses of the humble apartment. His first resolution was to get

beneath the bed; but that was objected to by the old woman as unwise, for,

as she remarked, that was the very first place his pursuers would likely

search. The quickness of the woman vindicated the superiority of her sex

in devising expedients.

"Tak that ladder and mount

up to the skylight," she cried; "open it, and try if it is big enough

toyou’re your body out. The roof o’ the house is the safest place in

it. Ye can lie there and crack to me through the window, and maybe I

may hand ye up something to cheer your sorrowfu’ heart."

The idea was excellent.

Maxwell immediately mounted got out at the skylight, and, laying his body

along the thatched roof, looked down upon his conditional protectress with

gratitude.

"Now," said the old woman,

"I can safely say ye’re no in my house. Dinna ye see how meikle ye

women hae improved, sin’ the days o’ our common mither, wha, if she had

but a tenth pairt o’ the wit o’ her dochters, might easily hae saved us

frae the burden o’ our original sin. Dinna ye see, that I can, by denying

your being in my house, save ane o’ my ain faith and my conscience, at the

same time."

Maxwell saw the importance

of the judicial construction which the woman was inclined to put upon her

answer, and it cheered his drooping spirits;--but he suspected the

possibility of the soldiers putting such a question as would place the old

woman’s conscience, whose sensibility might out strip the ingenuity of her

mind as well as himself, in jeopardy; and he therefore endeavoured to

prevail upon her to give up all her scruples, and deny him out and out.

Putting his hands to the sides of his mouth to prevent the sound from

escaping outwardly, and direct it down into the house, he said—

"I suppose you are well

acquainted with your Bible; and. no doubt it is from that precious volume

that you draw your reasons for not denying me to the soldiers. But, if I

recollect rightly, there is no express commandment against telling a white

lie to save a friend; for the ninth only forbids the bearing of false

witness against our neighbour, and I am only asking you to say a

word against truth for a friend."

"And a guid friend, in

troth," replied the woman, "ye are to come and. sit on my roof and try to

persuade me that a lee is no forbidden in the Bible. Did ye never read

that Ananias, and Sapphira his wife, were both, by the vengeance of the

Almighty, struck dead for telling a lee, far whiter in its complexion than

what ye sae cunningly would ha me to tell."

Caught by the biblical lore

of the woman, Maxwell changed his tactics, and endeavoured to maintain,

that, although lies were forbidden, there were some instances where they

were permitted.

"You are right, my good

lady," rejoined Maxwell, "but you must admit that, in some cases, even on

Bible authority, the end justifies the means, and untruths have, for

certain purposes, been permitted. It is, moreover, very remarkable that

you women have been selected, in preference to us men as the agents in

those instances where lies are permitted in Scripture."

"I dinna like flattery,"

interrupted the woman, with a quaint coquettish tone.

"For you are aware,"

continued Maxwell, "that Rahab received and concealed the two spies sent

from Shittim, and denied that she had seen them; and Rachel sat upon the

images, and said to her father, who searched for the same, that she could

not rise up, and therefore denied that she had taken them."

"Ay, and there is anither

instance ye micht hae mentioned," said the woman; "but I’m no sic a fule

as tell ye what it is; for I think it is mair against my sex than the

cases that hae enabled ye to pour down sae meikle abuse on us, wha are the

very fountains o’ mankind. But a’ thae lees werena justified, freend, nae

mair than were those tauld by Peter and Abraham."

This opposition on the part

of the woman, disconcerted Maxwell greatly; for at that very moment the

whole village was disturbed by the noise of the soldiers, who had arrived

and were searching every house in it. He, therefore, clung to the

concession already made by the woman, reminded her that he was not in

her house, and suggested the improbability of any question being put

as to his being on it.

In a little time the door

opened, and Maxwell could see, without being discovered, the men who were

thirsting for his blood, at least for the reward which the spilling of it

would yield them, enter the house, and search every corner of it for

himself. They repeatedly asked the woman if she had any person secreted in

it. To this she uniformly answered "No."

"Art thou sure, old lady,"

said the Lieutenant of the company, "that thou hast no man secreted in thy

house?"

"Sure am I o’ that,"

replied she; "and for the truth o’ what I say, I can appeal to a’ abune,"

giving a wink to Maxwell, who trembled at her bold indiscretion.

"But hast thou not this day

seen Maxwell of Orchardtown, the king’s outlaw, or heard of him, or

suspect where he is, or has been?"

"I hae seen nae man wham I

kenned to be Maxwell o’ Orchardtown," replied the close-sailing casuist.

After searching the house,

the men departed, but the noise in the village, still continued. Maxwell

felicitated himself on his escape; and the good woman proposed to give her

guest some porridge, provided she could devise any means of getting it up

to him, being unable to mount the ladder. This difficulty was overcome by

throwing a string up to Maxwell, who held the one end of it, while the old

woman tied the other to the dish. A good warm supper of our national meal

assuaged the pangs of a two day’s hunger, and the dauntless feaster

enjoyed, in the very midst of an uproar produced by the baying of the

bloodhounds tracking his course, that humble dish, with all the relish of

a professor of gourmandize picking the bones of an ortolan.

While the noise in the

village continued, Maxwell could not move. The fatigues of the day had

produced a lassitude which soon lulled him to sleep. As he was gently

falling into the arms of the drowsy god, he heard the old woman offering

up, with the greatest devotion, a prayer for his safety. Never did

religion appear to him so fascinating. The Castle of Orchardtown, with all

its grandeur, never presented to him a scene so full of picturesque

beauty, as this poor old woman in her little mud hut, addressing the

Almighty in her own simple terms, speaking the language of the heart, and

breathing the uncontaminated aspirations of a contrite spirit. Far less

did ever anything occur there to fill his heart with so engrossing an

interest. A stranger, unseen by her before, unknown to her, and liable to

be suspected by her, formed the subject of her devotional thanks and her

humble petitions—and that person was in the lion’s mouth—an

outlaw—proscribed by his king, and in the power of a poor old

woman--exposed to every privation, lying on a house top, and denied a

vision of the faintest ray of the rainbow of hope. In the devotional

contemplation of this subject, and with such feelings of satisfaction, the

persecuted owner of thousands lay down and slept on a roof of thatch.

A little before dawn,

Maxwell awoke. The sounds of the horsemen had ceased, and as yet the

inhabitants were asleep. He cried down to the old woman that it was time

he was off to the woods, where he knew a cave which would afford him

secure shelter during the day. His protectress requested him to remain

until he got something to eat; and, with all the expedition in her power,

proceeded to get something prepared for him. While engaged in this

occupation, the door opened, and a neighbour entered, requesting a light

wherewith to kindle her fire. Ignorant of the ingress of this visitor,

Maxwell asked, through the sky-light, if his breakfast was yet ready; and

the woman, who was in the act of lighting her peat, alarmed and terrified

at the supernatural voice coming from above, flew out of the house, with

the burning torch in her hand, exclaiming that the devil was in the house

of Betty Gordon, who was busy making his porridge. It was yet dark, and

the woman’s high tones—for she was truly alarmed—with the unusual

appearance of a lighted torch flaming in the street, roused the troopers,

who had taken up their quarters in the village for the night.

The sounds of the

collecting soldiers commenced—the supposed devil was sagaciously thought

to be the object of their search; and they hurried to the house. Maxwell,

however, had seen his danger, and coming down from his hiding place by the

back part of the house, crossed the Urr, and flew with the greatest speed

down to the Solway. The soldiers repeated their search. Everything was

examined, and one of them taking up the dish out of which Maxwell had

taken his supper, and to which the string was still attached, held it up

to his companions, as an evidence that the object of their search had been

on the roof of the house. As he held up the dish, something fell out of

it, which, on being examined, was found to be a diamond ring, which the

gratitude of the unhappy outlaw had induced him to give, in this delicate

manner, to his protectress. The valuable trinket was immediately laid hold

of by the officer of the company, who, placing it on his finger, held it

up, and asked how an outlaw’s ring looked on a loyal hand. Betty

vindicated her right to the ring, with all her powers of oratory, but to

no purpose. The only reply she got was, that, if she did not remain quiet,

she would be removed to Dumfries, and punished for harbouring a traitor.

The critical accuracy of this charge appearing to Betty to be exceedingly

doubtful, she defied the officer to his proof, arguing, with considerable

show of reason, and in her own particular style, that as, even by his own

allegation, the fugitive had lain on the top of her house, she could not

be said to have harboured him, any more than she did the rooks, who often

selected her roof to sit on, and caw their omens over the village. She

would not go the length of denying that he had been there; for she found

her conscience had now taken up the case, and casuistry had little effect

on that sturdy champion of the cause of truth.

Being able to procure no

trace from Betty, of the direction the fugitive had taken, the soldiers

betook themselves to a chance pursuit, which turned out to be well

scented; for Maxwell soon heard his relentless pursuers at his heels. It

was now grey dawn, and he had got to the water’s edge. The sounds

approached nearer and nearer to him, and his choice seemed to lie between

fire and water. Impelled by the keen spur of the fellest necessity, he

sprung into the water; and just as he had waded as far as to cover all his

body excepting his head which, in the dawn, could not be distinguished, he

saw the company of troopers dash at full speed along the edge of the bank.

So near were they, that he heard them mention his name, and could easily

learn, from their conversation, that they had secured the ring which he

had meant as a reward to the poor old woman who had treated him so kindly.

Maxwell now took his course

by Castle Gower, running at the top of his now diminished speed, and

producing, in the intensity of his struggles for life, such a degree of

heat throughout his body, that his wet clothes reeked. He presented thus

an extraordinary appearance, and attracted attention. Though he avoided

houses and sought the woods, he did not escape several people, who struck

with the figure of a man smoking like a kiln—out of breath and gasping,

yet still toiling on—running and stopping, and running again, and his

blood-shot eyes staring about him, as he expected every moment that death

was at his heels—concluded at once that he was a Jacobite flying for life.

The circumstance went from mouth to mouth, till it reached the soldiers,

who, making sure of the intelligence, turned and tracked their victim

through every evolution which his knowledge of the country enabled him to

make.

The race was unequal, so

long as Maxwell was obliged to keep even ground: but he soon got to the

thickets, and the troopers were obliged to dismount, and follow him

through the trees. He got now among the old woods of Munshes, striking up

to the high ground as his best refuge. He was now, however, in the view of

his pursuers, who, coming from off their horses, were comparatively fresh

and able for the pursuit. With drawn swords in their hands, which

glittered with a fearful brightness amidst the dark green leaves of the

old oaks, they dashed on, and poor Maxwell saw, with dismay, that his

career was finished.

Providence, how strange are

thy ways! At the very moment when Maxwell thought himself about to resign

his life he fell headlong into a cleft of an old quarry, which had been

opened, on the lands of Barchan, by the old Maxwell of Munshes, who

married the heiress of Tinwald. There he lay senseless and motionless, as

much beyond the fear of his foes as if he had got a free pardon; but his

relief was the insensibility of a swoon; and when he recovered his senses,

he heard the whoop of the soldiers dying away in the distance. They had

passed over him, continuing their course, in the belief that he had

doubled a corner of the rock, and proceeded in the direction of the river.

In this situation, Maxwell

considered what course he should now take. He conceived himself unsafe

where he lay, for he knew that the moment the soldiers cleared the woods

and saw no trace of him beyond, they would return and search for the place

where he lay, and, in all probability find him. The thought of dying in a

cave, without room for the play of his arms, like a badger baited by

terriers, suited not the taste of Maxwell, who was determined to sell his

life at a dear price. Climbing out of the cave, he made again for the

Solway, in the expectation of getting into a boat, which, as he passed

before, he saw lying on its banks. This expectation did not fail him—the

boat was still there—in he vaulted, and, taking the oars into his hands,

pulled away with all his strength.

In a short time he had got

a considerable distance from shore and conceiving himself now safe, at

least, for a time, the energies which the instinctive love of life had

called up, suddenly failed, and he lay down in the bottom of the boat, in

a state of exhaustion approaching to inanity. The novelty, if not the

danger of his situation, had no power sufficient to rouse his torpid

faculties—a cataleptic influence seized every fibre of his body, and an

incubus of fearful weight pressed upon him, while his imagination

wandered, and dreams of battles and blood came over him, producing

convulsive starts and deep groans.

A dawning sense of the

danger of his situation at length beamed on his reviving imagination, but,

even after he was aware of the true nature of his condition—at sea in an

open boat—his exhausted limbs denied their office, and he remained for

some time in that situation, which is so often experienced in dreams, when

the mind is awake to a supposed danger, but the energies of safety are

asleep. When he fully recovered his faculties, and looked up and around

him, he discovered that he had drifted, with a receding tide, far down the

Solway, and that an easterly wind was beginning to ruffle the waves, and

impel the boat faster in its course. A new danger now threatened him. The

wind was fast increasing in intensity, the boat was clearly in full speed

for the ocean, and he perceived, with dismay, that he had escaped from a

death on land, to be swallowed up in the waves of the Atlantic.

The horrors of this

apprehension did not, however, prevent Maxwell from using the powers the

Almighty had still left him, with a view to save his life; but all his

energies did not suffice to enable him to dispute space with the dire

enemies he had now to contend with. He was now beyond the sight of land—a

deep fog surrounded him on all sides— the wind howled, and the waves

lashed round the small boat, as if they demanded the craft to resign their

victim. Maxwell continued to pull with his utmost power, but his efforts

only made more evident the insurmountable strength of the angry spirit of

the incipient storm; yet still he toiled, determined to die at the oar

rather than resign the last flickering hope, that gilded, with its faint

beam, the verge of his imagination.

Some hours passed in this

dreadful struggle, and nature was again exhausted. His arms became weak

and palsied, and the oars fell from his grasp into the sea, carrying with

them the last hope of life. Resigned, at last, to a fate which he had so

often and so narrowly escaped—death, so terrible even in its mildest

aspect; but, when marshalled in, and surrounded by the dread furies that

wait on the angry spirit of the storm, how indescribably awful!—Maxwell

looked silently and sadly over the boiling waters, and waited his doom. So

certain, so near, seemed to him that consummation of his woes, that he

already conceived himself as no longer belonging to the living. The death

of hope was the dissolution of his powers of perception; and his eye was

already fixed on the ghastly forms which despair throws round its victim,

as if in preparation for the final onset of the mighty king.

"Hallo!" thundered a

stentorian voice in the ear of the entranced and already half-dead victim.

Maxwell started to his feet, and beheld a boat alongside, with people

endeavouring to throw grappling irons, to bind the boat in which he was,

to the welcome stranger. In a short time he was removed into the other

boat; which, being supplied with sails, was, in a moment, in full flight

for the land. Having recovered himself, he looked round, and saw sitting

in the stern two of the king’s troops, who had been sent off to secure

him. "Again saved, and again consigned to death," he muttered to himself:

and, folding his arms in his breasts he looked sternly at his foes.

The boat soon approached

the land. Maxwell had been allowed to remain without manacles, for the

violent motion of the boat rendered it impossible for the soldiers to fix

them, and they reserved that duty till they should get into smooth water.

The surf on the shore, however, rendered that operation more difficult

than in the open sea; and a greater obstacle still remained in the

sickness of the soldiers who, unaccustomed to such rough sailing, hung

over the gunwale, and vomited into the sea. On reaching the land, the boat

struck violently on the beach, approaching and receding alternately, and

producing great annoyance to the sick men, who, Maxwell observed, were

totally unable to bind or guard him, while the sailors seemed to concern

themselves very little as to whether he remained or escaped. Taking

advantage of this favourable state of matters, he plunged into the sea,

and in a few minutes was on dry land.

On looking round him, he

saw that he was landed near to the place from whence he had sailed; but no

rest was yet in reserve for him. The remainder of the soldiers were on

their way to the beach to meet their companions. He resolved to proceed

again to the cave, and hastened with all the quickness in his power, that

he might secrete himself before they came up. The beagles were, however,

again at his heels, and the race was again for life. He soon reached the

woods, and as darkness was fast closing in, he began to entertain a slight

hope of ultimate escape. All was quiet save the flutter of a few small

birds. The wind had fallen, and the contrast which the scene now before

him presented, to that he had witnessed so shortly before, was so

remarkable, that he stood for a moment to contemplate it, and wept for the

cause which had banished him from his domains, and filled his cup with

such bitterness of sorrow. As he dashed the tears from his eyes, on

resuming his race, the sounds of the soldiers were again recognised by

him; and, on turning round, he saw them at no great distance, while he was

yet a considerable way from the cave. The advantage they had over him, by

being fresh and vigorous, soon became manifest. They gained upon him at

every step, and he was now in the same danger as when formerly Providence

snatched him from his enemies and hurried him under the ground. It was now

impossible to reach the quarry. The eyes of the soldiers were fixed upon

him, as if determined that he should not again escape, and he now finally

resolved to take his stand. Determined to die rather than yield, he placed

his back against an oak, and waited the coming of his foes. The sergeant

of the company had been considerably a-head of his companions during the

chase, and came up to the desperate man alone. He fell in an instant, shot

by a concealed pistol which Maxwell drew from his pocket; and his sword

was immediately seized, to enable his victor to barter his life for as

many of the lives of his persecutors as he could secure. The conflict was

short but terrible. Three men fell by the hand of Maxwell, and he resigned

his life, covered with many wounds.

The body of the unfortunate

but brave heir of Orchardtown was taken first to Dalbeatie. Betty Gordon

requested that, till it was otherwise disposed of, it might lie in her

house. The request was not denied; and many people having heard of the

brave manner in which he had met his fate, assembled to see the remains of

a man who exhibited on his person no fewer than fifteen sabre cuts. The

Spartan mothers would in vain have augured, from the position of his

wounds, that he died with his back to his foes. A safer construction would

have been, that his death was doubly glorious; for he gave his breast to

his enemies, and his defenceless back received only those wounds which

that could not contain. |