|

IT may be assumed to be a generally accepted proposition

that every creature has its own appointed use and purpose, and has its place

in the whole scheme of creation; yet it is also true that we constantly hear

animals,—beasts or birds,—spoken of as belonging to one or other category of

the noxious or innocuous. We have indeed a somewhat unpleasant word to

designate the former, a word that has travelled far from its original

meaning; we call them ‘vermin.’ When, however, we give the matter closer

consideration, it will be found by no means an easy task to draw hard and

fast lines separating, as it were, the sheep from the goats. We find it to

be a matter of proportion, circumstances, and surroundings, just as ‘dirt’

was properly described as matter in the wrong place.

In India, in districts where

game is still plentiful, the tiger is looked upon by the native cultivator

as a benefactor who keeps down the wild animals that devastate his fields;

but when game is scarce or non-existent, and the tiger preys systematically

on his cattle, he is addressed with opprobrious epithets, and the assistance

of the Sahibs is invoked for his destruction. Here in our own country we

have got into a way of loosely classing certain beasts and birds as

'vermin,' to be destroyed in every way possible without further trial, and

of this habit it may be of interest to consider a few examples.

To take first our own larger

carnivora, the fox, the badger, and the otter, there is undoubtedly

something to be said on both sides of the question. It must be admitted at

once that in the sheep-farming Highlands of to-day the fox is a nuisance,

and cannot be tolerated, but in the Lowlands the case is different. Leaving

aside entirely the question of fox-hunting as a sport, the balance of

evidence on the whole seems in favour of the fox. His chief food is usually

the rabbit, and surely there are more than enough of these for him and for

us; but he is also fond of much smaller game, such as field mice and voles,

for which he hunts assiduously, as well as of beetles and other of the

larger insects ; on the whole, the verdict of an intelligent agricultural

jury will be 'not guilty.'

To turn to another of our

larger carnivora, the badger, this is a long-suffering animal which, on

account of ignorant prejudice, has been so persecuted that it is now rare in

Scotland, although comparatively plentiful in some districts of England,

where its harmlessness is probably better understood. An omnivorous feeder,

living on roots, vegetables, fruits, beetles and insects, reptiles and mice,

with a special love for honey and wasp-grubs, he is decidedly useful on the

whole; his fondness for an occasional change in the way of a nest of young

rabbits being about the sole charge that can fairly be brought against him.

The case of the otter, the

next of our larger animals, is not quite so plain. Where fish are plentiful

his diet consists almost entirely of them, and at times he destroys more

than he consumes. In his favour it is to be recorded that eels are a special

favourite with him, and there is certainly no worse enemy than the eel to

salmon and trout in their early stages. When fish are scarce, the otter

contents himself with frogs, young rabbits, indeed with anything he can come

by. There is on the whole, therefore, not very much to be said in his favour;

but his mode of life and nocturnal habits enable him to take pretty good

care of himself; indeed the otter is more plentiful than many people

imagine, and there is not much fear of his extermination for a long time to

come.

It must be conceded that it

is difficult to make much of a case in favour of the wild cat on the score

of usefulness, under present-day conditions ; their numbers, however, are

now so few that they can do little damage in the wild and remote localities

where they still exist. A few mountain hares or grouse are surely not too

high a price to pay for the continued existence of such a magnificent type

as a member of our Scottish fauna.

Much the same is the argument

in favour of a lenient judgment of that beautiful and graceful animal, the

marten, which one fears is still nearer to the vanishing point. Like the

wild cat, and unlike the otter, they are easily trapped, and the only hope

for them is that some of our larger proprietors may extend protection to

them in time.

For the polecat, one fears

that it is already too late to put in any plea ; but if, as seems probable,

our tame ferret is a domesticated race of the polecat, it is likely to be

with us in this form for many a day.

In the case of the stoat

there is much more and stronger evidence for the defendant. It cannot for a

moment be denied that it is a some what dangerous neighbour for game of all

kinds, yet it must be kept in mind that the stoat is a determined foe of the

rat, as well as of the lesser rodents generally, and the rat is perhaps the

worst enemy of all, both to the game preserver and to the farmer. The

growing plague of rats is becoming a very serious, and even threatening

evil, and it may be fairly urged that the stoat in moderate numbers is, on

the balance of evidence, entitled to a verdict of 'not proven,' at least.

For the little weasel the

case is stronger still; the farmer has no better friend, and those who

remember the plague of voles which not so long ago caused much damage over

large areas of Scotland, will surely agree that here we have a distinctly

useful member of the community. It may be noted in passing that few seem to

know that in the far north the weasel, like the stoat, becomes white in

winter, and is the M. nivalis of Linnaeus. This has also been known to occur

in Switzerland, although not in Great Britain. The so-called 'blood-sucking'

propensities of this family are now admitted to be altogether imaginary.

So much has been recently

written concerning the squirrel and its malpractices that it is unnecessary

to say more than that it has been abundantly proved to be most destructive

in young plantations, and must be kept rigorously down. Sad, too, to say the

squirrel seems of late to be developing a vitiated taste for the eggs and

young of small birds, of which I have had specific proof. Mention has

already been made of rats and voles, but a plea must be recorded for the

water vole, usually and wrongly called the water rat. This pretty little

creature, more of a beaver in miniature than a rat, is a vegetarian and must

be classed as innocuous, excepting in the rare cases where his tunnelling

may endanger the embankments of streams or reservoirs, or where in severe

winters he causes damage to the osier-beds by barking their shoots.

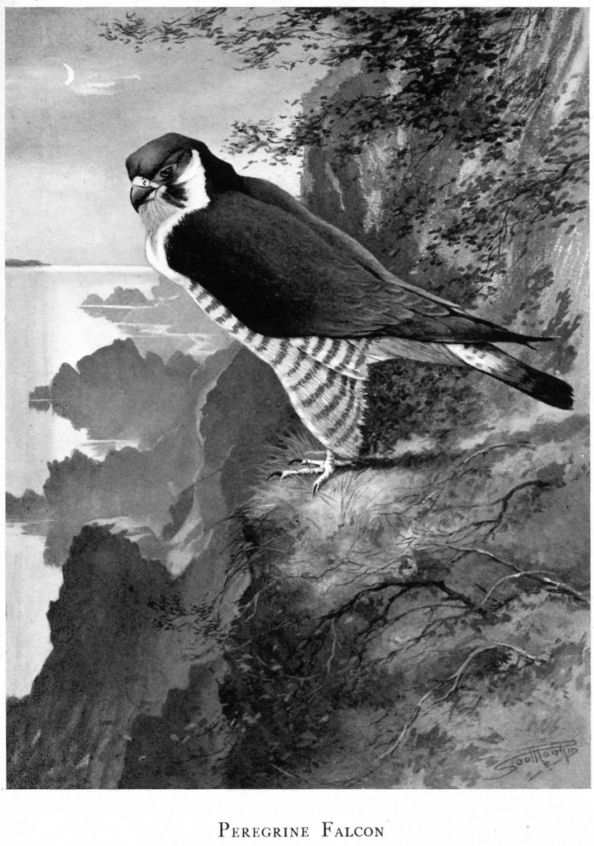

Turning now to our British

birds, we find a long list against whom sentence of death, even to

extermination, has been ruthlessly decreed. That grand bird the erne, or sea

eagle, is already gone as a breeding species; his congener, the golden

eagle, survives in some numbers owing to the protection accorded to him in

some of the larger properties in the north, and such is also the case with

the peregrine falcon. It is sad that one cannot say the same for the osprey.

One after another of its former stations have been cruelly robbed and

harried, so that it is to-day doubtful whether the osprey may still be

retained in our list of British breeding species. The kite, too, with the

exception of a very few in Wales, watched and guarded day and night, is

gone, and so also are practically the harriers.

Of those of our birds of prey

still remaining to us, the common buzzard is certainly deserving of

protection. Feeding chiefly on moles, mice, voles, the smaller reptiles and

insects, the good service it renders may well be placed against a very

exceptional delinquency in the shape of a young rabbit or hare. In quite as

great a measure is this the case with the kestrel, whose graceful hovering

flight as it pursues its constant hunt for mice and voles forms so

interesting a note in our country landscape, yet to how many of our keepers

are these useful birds merely 'hawks,' and therefore to be slain at sight?

One would think that it would

hardly be necessary to put in a word of defence for our owls, yet how often

do these, too, hang in the keeper's museum in pitiful if mute protest

against ignorance and incompetence? For the raven one would merely say that

it were a pity that so grand a bird should be exterminated, but the hooded

or carrion crow is a nuisance, with difficulty to be kept within bounds,

coming as they do in flocks on migration from the north; and the jackdaw of

late years appears to increase so rapidly that there, too, a stringent check

seems called for.

Two others of the Corvidae,

the magpie and the jay, are each so beautiful an addition to our

woodlands that, in moderation, they surely repay the little they cost. The

rook question is a much larger one. In some quarters their increase seems to

have passed all bounds of moderation. They have also developed new and

unpleasant habits and appetites, hunting and destroying nests and eggs like

their near relatives, the crows. On the other hand, their good deeds must

not be forgotten, and the conclusion seems to be that the true balance in

numbers must be sought for. The sparrow pest is another subject of much

interest to agricultural and gardening readers; if the gamekeepers would

spare a few of the sparrow-hawks, and such lovely summer visitors as that

fine little falcon the hobby, it would help; but as things are at present,

the only remedy seems to lie in the way of co-operation and destruction.

Much more might be written on

the balance of nature and man’s constant interference, but the above may,

perhaps, serve to cause some who have the power of life and death over these

creatures to pause and weigh the evidence more carefully before irrevocable

sentence is pronounced. It is pleasant to know that there is already a

marked improvement in this direction among the more intelligent keepers.

Within a few miles of where these lines are written, the peregrine, the

buzzard, the raven and the badger all breed yearly, and one can but hope

that, before long, such will be the rule and not the exception. |