AS might have been expected, there has gathered round the

mass of lawlessness represented by the foregoing list of detections a

cluster of stories of cunning and daring, and wonderful escapes, which casts

a ray of interest over the otherwise dismal picture. From a large number

that are floating about, I can only give a few representative stories, but

others can easily supply the deficiency from well-stocked repertories.

After a School Board meeting held last summer, in a

well-known parish on the West Coast, the conversation turned on smuggling,

and one of the lay members asked one of the clerical members, "Did not good,

pious men engage in these practices in times gone by?" "You are right, sir,

far better men than we have now," replied the Free Kirk minister. This is

unfortunately true, as the following story will prove. Alasdair Hutcheson,

of Kiltarlity, was worthily regarded as one of the Men of the North.

He was not only a pious, godly man, but was meek in spirit and sweet in

temper—characteristics not possessed by all men claiming godliness. He had

objections to general smuggling, but argued that he was quite justified in

converting the barley grown by himself into whisky to help him to pay the

rent of his croft. This he did year after year, making the operation a

subject of prayer that he might be protected from the gaugers. One time he

sold the whisky to the landlord of the Star Inn, down near the wooden

bridge, and arranged to deliver the spirits on a certain night. The

innkeeper for some reason informed the local officer, who watched at

Clachnaharry until Alasdair arrived about midnight with the whisky carefully

concealed in a cart load of peats. " This is mine," said the officer,

seizing the horse's head. "O Thighearna, bhrath thu mi mu dheireadhl"

(O Lord, thou hast betrayed me at last!) ejaculated poor Alasdair, in such

an impressive tone that the officer, who was struck with his manner, entered

into conversation with him. Alasdair told the simple, honest truth. "Go,"

said the officer, "deliver the whisky as if nothing had happened, get your

money, and quit the house at once." No sooner had Alasdair left the Inn than

the officer entered, and seized the whisky before being removed to the

cellar. I would recommend this story to the officers of the present day.

While they ought not to let the smuggler escape, they should make sure of

the purchaser and the whisky. There can be no doubt that "good, pious" men

engaged in smuggling, and there is less doubt that equally good, pious

men—ministers and priests— were grateful recipients of a large share of the

smuggler's produce. I have heard that the Sabbath work in connection with

malting and fermenting weighed heavily upon the consciences of these men—a

remarkable instance of straining at the gnat and swallowing the camel.

John Dearg was a man of different type, without any pretension to piety, and

fairly represents the clever, unscrupulous class of smugglers who frequently

succeeded in outwitting the gaugers. John was very successful, being one of

the few known to have really acquired wealth by smuggling. He acted as a

sort of spirit dealer, buying from other smugglers, as well as distilling

himself. Once he had a large quantity of spirits in his house ready for

conveyance to Invergordon to be shipped. Word came that the officers were

searching in the locality, and John knew his premises would receive marked

attention. A tailor who was in the habit of working from house to house

happened to be working with John at the time. Full of resource as usual,

John said to the tailor, "I will give you a boll of malt if you will allow

us to lay you out as a corpse on the table.'' "Agreed,'' said the plucky

tailor, who was stretched on the table, his head tied with a napkin, a

snow-white linen sheet carefully laid over him, and a plate containing salt

laid on his stomach. The women began a coronach, and John, seizing the big

Bible, was reading an appropriate Psalm, when a knock was heard at the door.

"I will call out," said the stretched tailor, "unless you will give me two

bolls," and John Dearg was done, perhaps, for the first time in his life.

John went to the door with the Bible and a long face. "Come in, come in," he

said to the officers, "this is a house of mourning—my only brother stretched

on the board!" The officers apologised for their untimely visit, and hurried

away. "When did John Dearg's brother die?" enquired the officer at the next

house he called at. "John Dearg's brother? Why, John Dearg had no brother

living," was the reply. Suspecting that he had been out-witted, the officer

hurried back, to find the tailor at work, and all the whisky removed and

carefully concealed.

A good story is told of an Abriachan woman who was

carrying a jar of smuggled whisky into Inverness. The officer met her near

the town and relieved her of her burden. "Oh, I am nearly fainting," groaned

the poor woman, "give me just one mouthful out of the jar." The unsuspecting

officer allowed her the desired mouthful, which she cleverly squirted into

his eyes, and she escaped with the jar before the officer recovered his

sight and presence of mind.

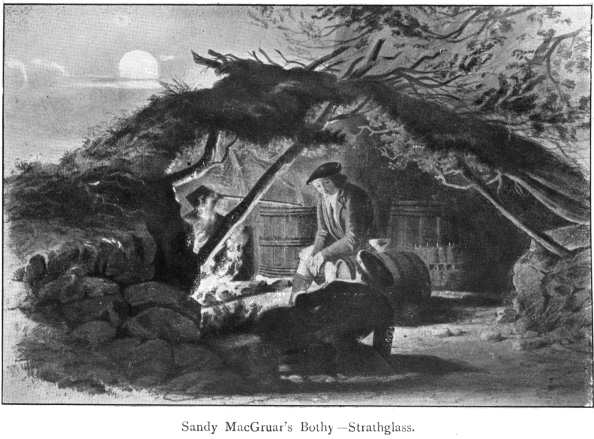

The following story, told me by the late Rev. John

Fraser, Kiltarlity, shows the persistence which characterised the smugglers

and the leniency with which illicit distillation was regarded by the better

classes. While the Rev. Mr. Fraser was stationed at Erchless, shortly before

the Disruption, a London artist, named Maclan, came north to take sketches

for illustrating a history of the Highlands, then in preparation. He was

very anxious to see a smuggling bothy at work, and applied to Mr. Robertson,

factor for The Chis-holm. "If Sandy MacGruar is out of jail," said the

factor, "we shall have no difficulty in seeing a bothy." Enquiries were

made, Sandy was at large, and, as usual, busy smuggling. A day was fixed for

visiting the bothy, and MacIan, accompanied by Mr. Robertson, the factor,

and Dr. Fraser of Kerrow, both Justices of the Peace, and by the Rev. John

Fraser, was admitted into Sandy's sanctuary. The sketch having been

finished, the factor said, "Nach eil dad agad Alasdair?" ("Haven't

you got something, Sandy?") Sandy having removed some heather, produced a

small keg. As the four worthies were quaffing the real mountain dew, the

Rev. Mr. Fraser remarked, "This would be a fine haul for the gaugers—the

sooner we go the better." It was the same Sandy who, on seeing a body of

Excise officers defile round the shoulder of a hill, began counting them—aon,

dha, tri, but, on counting seven, his patience became exhausted and he

exclaimed, "A Tighearna, cuir sgrios orra!" ("Lord, destroy them!")

A Tain woman is said to have had the malt and utensils

ready for a fresh start the very evening her husband returned home from

prison. Smugglers were treated with greater consideration than ordinary

prisoners. The offence was not considered a heinous one, and they were not

regarded as criminals. It is said that smugglers were several times allowed

home from Dingwall jail for Sunday, and for some special occasions, and that

they honourably returned to durance vile. Imprisonment for illicit

distillation was regarded neither as a disgrace, nor as much of a

punishment. One West Coast smuggler is said to have, not many years since,

suggested to the Governor of the Dingwall jail the starting of smuggling

operations in prison, he undertaking to carry on distillation should the

utensils and materials be found. Very frequently smugglers raised the wind

to pay their fines, and began work at once to refund the money. Some of the

old lairds not only winked at the practice, but actually encouraged it.

Within the last thirty years, if not twenty years, a tenant on the Brahan

estate had his rent account credited with the price of an anchor of smuggled

whisky, and there can be no doubt that rents were frequently paid directly

and indirectly by the produce of smuggling. One of the old Glenglass

smugglers recently told Novar that they could not pay their rents since the

black pots had been taken from them.

Various were the ways of "doing" the unpopular gaugers. A

cask of spirits was once seized and conveyed by the officers to a

neighbouring inn. For safety they took the cask with them into the room they

occupied on the second floor. The smugglers came to the inn, and requested

the maid who was attending upon the officers to note where the cask was

standing. The girl took her bearings so accurately that, by boring through

the flooring and bottom of the cask, the spirits were quickly transferred to

a suitable vessel placed underneath, and the officers were left guarding the

empty cask. An augur hole was shown to me some years ago in the flooring at

Bogroy Inn, where the feat was said to have been performed, but I find that

the story is also claimed for Mull. Numerous clever stories are claimed for

several localities.

An incident of a less agreeable nature ended fatally at

Bogroy Inn. The officers made a raid on the upper end of Strathglass, where

they discovered a large quantity of malt concealed in a barn, which the

smugglers were determined to defend. They crowded behind the door, which was

of wicker-work— dorus caoil—to prevent it being forced open by the

gaugers. Unable to force the door, one of the officers ran his cutlass

through the wicker-work, and stabbed one of the smugglers, John Chisholm,

afterwards called Ian Mor nan Garvaig, in the chest. Fearing that

serious injury had been done, the officers hastened away, but, in the hurry,

one of them fell over a bank, and was so severely trampled upon and kicked

by the smugglers, that he had to be conveyed to Bogroy Inn, where he died

next day. Ian Mor, who only died a few months ago, showed me the scar of the

wound on his chest. He was another man who had gained nothing by smuggling.

One of the most complete detections and seizures made in

my time took place in Achanalt deer forest. The Beauly officers discovered a

quantity of malt and a bothy in course of construction in Coulin forest,

between Kinlochewe and Torridon. On an early return visit they found that

the malt had been removed, and that the bothy was still unfinished, the

inference being that the smugglers had become aware of their first visit and

had taken alarm. Careful searching failed to discover the malt, and the

officers suspected that it had been conveyed across the hills to Achanalt, a

considerable distance. The Dingwall officers, under pretence of fishing,

visited the locality, and, after two days' searching, discovered the bothy

in full working order in a very lonely spot high up in Achanalt forest.

There being only two officers, one said to the other, "Is it quite safe to

enter the bothy? There may be several smugglers, perhaps the worse of drink;

they may murder us and bury us in the moss!" " Well," replied the other

bravely, "I am quite prepared to go." To prevent escape a rush was made to

the bothy, where two men were found busy, the still being on the fire

running low-wines. Addressing the more elderly man, one of the officers

said, "Bha sibh fad' an so! " "Bha, mo thruaighe, tuilleadh is fada!"

was the sad reply. ("You have been long here!" "Yes, alas, too

long!") Pretending help was near, the officers requested the smugglers to

get ready for proceeding to Dingwall. But this they resolutely refused to

do, evidently guessing, as time passed, that more officers were not

forthcoming. Seeing they were only man for man, and that friends might at

any moment come to visit the smugglers, the officers concluded that

discretion was the better part of valour, demanded the men's names and

addresses, which subsequently proved to be altogether false, placed all the

utensils and materials under seizure, and allowed the smugglers to go. They

fled like deer over the bogs and rocks, and were soon out of sight. The

bothy contained a copper still, stillhead and worm, and a complete set of

the usual utensils. There was no whisky, but the receiver connected with the

still contained a quantity of low-wines, and there were several vessels

containing worts ready for distillation. The smugglers had actually cut and

dried peats for their own sole use, erected a kiln with perforated iron

plates to dry their malt, and set up rollers to crush it. They had a

sleeping bothy, with bags full of dried grass for beds and some blankets.

Small quantities of tea, sugar, bread, butter and "crowdie" (dried curds)

were found, and several herring hung up drying in the smoke of the

still-fire. At some distance from the bothy was a heap of draff, to which

the deer had a well beaten track. Having demolished all that could be

destroyed, the officers conveyed the still, head and worm to Auchanalt

Station, where they arrived in the gloaming, tired and wet, but quite

pleased with their exploits, regretting only that they were not able to

bring the smugglers also. The smugglers must have been at work for months in

their extensive establishment, and the officers afterwards learned that on

their way to the station they had passed close by the spot where a cask of

whisky was buried in the moss.

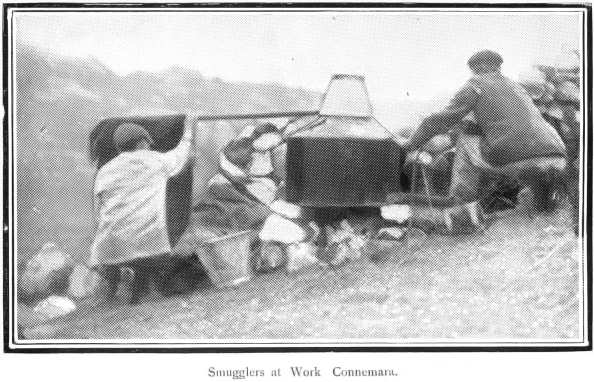

Melvaig and Loch Druing smugglers, on account of their

remoteness and the difficulty of visiting the localities without being seen,

caused the officers much trouble and anxiety. The Gairloch staff planned a

raid on the latter place, and leaving Poolewe soon after midnight, searching

suspected places at Inverasdale on the way, arrived very early in the

morning at Loch Druing, where the smugglers were in the habit of working in

the barns and outhouses which rendered detection very difficult. Clear

evidence of distilling having taken place during the night was found at one

of the dwelling-houses, but on entering the officers discovered that the

still had been removed just before their arrival. In spite of their

precautions the officers had been observed passing one of the crofting

hamlets on the way, and a friendly messenger was despatched to Loch Druing

to warn the smugglers. All the brewing utensils were discovered in a remote

outhouse, but the most careful search failed to discover the still. In

course of the search, however, fresh marks of excavation in the moss were

noticed, and after close examination a cask containing about fifteen gallons

of whisky, distilled during the night, was found buried in the moss about

200 yards from the dwelling-house. On account of the size and weight of the

cask and the distance to Poolewe, four or five miles, being only a very

rough track across the moor, the removal of the cask by the officers was

impracticable, and no help could be expected from the smugglers. It was

therefore decided to destroy the cask and its contents. After a sample had

been secured, the cask was set up on end in the hole where it had been found

buried, and as one of the officers was in the act of smashing in the head

with a large stone, half a dozen men rushed from the houses with a

terrifying yell that would have done credit to Red Indians on the warpath!

The officers held their ground, although at some risk of personal violence,

and the precious contents of the cask were destroyed, to the great sorrow of

the angry smugglers and their friends. Although only two families reside at

Loch Druing, nearly a score of men and women, several of them from

considerable distances, were assembled to assist at the smuggling, and it is

evident that much whisky must have been consumed during the operation. The

smugglers being in fairly comfortable circumstances, legal proceedings, were

taken against them and a substantial penalty was imposed. After some delay

the fine was duly paid, the cheque being actually issued by a neighbouring

Justice of the Peace ! Another proof of the tolerance with which even the

better classes regard these illegal practices.

The Loch Druing smugglers are said to have frequently

sunk their still in the loch, attaching a cord and small float, by which it

could be hauled out when required.

The following is a good example of the daring and

resource of the Inverasdale smugglers. Pressed and practically driven by the

officers from their own local haunts, they ventured to start operations on

the opposite side of Loch Ewe. While collecting the cattle in the dusk the

Inverewe herd came accidentally on their bothy. Aware of the strong aversion

of the laird, a strict temperance man, to smuggling, they became alarmed.

Pretending to give a warm welcome to the herd, they plied him with strong

whisky until he was dead drunk. They then bundled him into a corner of the

bothy, removed all their materials and utensils, and boated them back across

the loch to their own side. A party from the farm searched all night for the

missing herd, who did not waken from his drunken sleep till next morning,

when he returned and related his experiences which fully accounted for his

sudden and unexpected disappearance. Long before then the smugglers and

their belongings were safe on their own side of Loch Ewe.

Another notorious smuggling district is Alligin, on Loch

Torridon. This is the only place where the Gairloch staff was deforced. Late

in the evening they discovered a bothy near the base of Ben Alligin, and on

attempting to enter one of the smugglers rushed to the door with a spade and

threatened to cleave the head of any one who dared to come in. Knowing the

desperate character of the men, the unfriendly feeling of the whole

township, the probability of help for the smugglers being near, and the risk

of serious personal injuries, the officers desisted and duly reported the

incident, having recognised the smuggler who threatened them. A warrant was

issued for his arrest, but on a surprise visit by the Revenue and Police

Officers to his home, he could not be found. When the search was over the

aged mother, quite overcome, knelt at the door, and in eloquent Gaelic

fervently thanked the Almighty for having protected her dear boy. It was an

impressive, pathetic scene, which will not be readily forgotten by those who

witnessed it. It was afterwards ascertained that the son had not dared to

sleep at his own home for upwards of six months. Several detections and

seizures have been made in the Alligin district. A recently used bothy was

discovered on the margin of a small hill-loch in which there was a

heather-clad little island. Close search was made for the still, which could

not be found anywhere, although the worm was found concealed among rough

rocks at some distance. Suspecting that the still might be concealed on the

island, the shallowest part of the water was selected, and one of the

officers waded across some twenty yards to the island, where he found a fine

copper still buried in the moss and carefully covered with heather. The

articles were carried away in triumph, and it was said afterwards that this

clever detection caused much surprise and disappointment among the

smugglers.

On one occasion a bothy was found within two hundred

yards of Alligin Schoolhouse. Unfortunately the operations had been

successfully completed before discovery. What struck the officers was the

low moral tone which permitted of smuggling being carried on in such close

proximity to the school, where the children must have been fully aware of

what was doing, and the callous indifference which exposed the children to

the evil example and influences of such illegal practices and of the

debasing scenes which generally took place in and around these bothies.

Across the hills from Alligin is Diabaig, another

troublesome place. An important seizure of a large new copper still, with

materials and brewing utensils, was made near this place in a seaside cave

which has been frequently used for smuggling. A concealed channel was cut

from a stream on the hill-side leading water over the cliff to the cave, to

which access can only be obtained on one side. Another important seizure was

made at Upper Diabaig, where the bothy was neatly built in an old sheep "fank."

The still had been removed before the officers arrived, but all other

utensils were found and destroyed. These Diabaig smugglers are very

persistent, the locality being wild and remote and difficult of access.

Their own local saying is—"Is fada Diabaig bho lagh." (" Diabaig is

far from law.") The Tarvie and Garve smugglers have been very active for

years. A large seizure was made in Tarvie plantation, where the bothy

contained a complete set of brewing utensils and fermented worts. A

concealed channel conveyed water from a rivulet at some distance. When the

officers arrived no one was in the bothy, but the fire was burning, ready

for beginning distillation. In this bothy, which was not far from the

dwelling-houses, were found several domestic articles among them what had

never before been seen by the officers in a bothy, a bellows for blowing the

fire. Careful search failed to find the still, and when the bothy was set on

fire the young plantation had a narrow escape from burning, several trees

having to be cut down to prevent the fire from spreading. Soon after a bothy

took fire near Loch Achilty, and a large extent of wood and heather was

burning for nearly three weeks, when the fire was extinguished with some

difficulty. The damage and expense were considerable, and the occurrence

directed the attention of the Laird and of the shooting tenant to the

smugglers, who were warned and threatened, and this has led to less activity

on their part in this district.

It has been stated how frequently the officers failed to

find the stills. This is explained by the importance and value of that

utensil, especially when made of copper, and the great care taken

to remove and conceal it when not in active use. It is the invariable

practice of smugglers who generally distil at night to remove the still from

the bothy to some secure place in the morning. The following story, told to

me by Rev. Dr. Aird of Creich, is a good illustration of the ingenuity

exercised to secure the still from seizure. The Nigg smugglers were

frequently at work in the caves of the Northern Cromarty Sutor, which are

difficult of access, and the officers could never succeed in finding the

still. "Where think you," asked the Doctor, "did the rascals hide the

still?" I replied I could not guess, knowing how cunning and resourceful

smugglers were as a rule. "Under the pu'pit!" chuckled the doctor. But, I

asked, how did they obtain entrance to the Church? The beadle must have been

in collusion with them. "Of course he was, the drucken body! " answered the

doctor. Before the abolition of the Malt Tax all mills and kilns had to be

visited periodically by the Excise officers with the view of malt being

dried and ground for the smugglers. One of the Glenurquhart millers used to

tell of his narrow escape on one of these visits. The local officer came to

the mill as a parcel of malt was being ground. The miller, though much

upset, calmly engaged in conversation with him for a little, but suddenly

remarking that "the hopper was running empty," rushed upstairs and quickly

emptied a bag of oats which was standing close by on top of the malt in the

hopper. The officer followed leisurely and examined the contents of the

hopper, remarking to the miller, "Oh, you are grinding oats to-day." So the

miller narrowly escaped not only the loss of his good name for honesty, but

also the forfeiture of the malt and a heavy penalty.

Another of the Glen Urquhart millers was actually engaged

in distillation in one of the outhouses connected with the mill when the

officer, after a long tramp, arrived late in the day, looking tired and

weary. Having been observed coming, the miller met him near the house, which

was situated between the road and the mill, and with Highland hospitality

invited him to have a cup of tea after his long journey. While the tea was

getting ready the bottle was produced and the officer was pressed to take a

stiff glass of whisky, the miller apologising for the slowness of his

housekeeper in bringing the tea. By the time the tea was over, the miller's

smuggling friends had removed all the smuggling materials and utensils to a

safe place of concealment, and on his visit to the mill and kiln the officer

found everything regular, never suspecting that he had been so neatly and

cleverly outwitted.

Mr Paterson, Foulis Mains, tells a good story of a

smuggler and his daughter, Moll. In the days before the Malt Tax was

abolished, they were both in the barn putting malt into bags to be conveyed

to the kiln for drying, when an officer arrived. Failing to force the door,

which was strongly barricaded, he removed a small window and inserted his

head, when Moll seized him by the beard and held him fast. The father,

doubling his efforts to secure the malt, called to Moll, "Cum greim

cruaidh air a bheist!" (Haud a hard grip of the beast!), but shouted in

English, "Let the gentleman go, Moll!" He repeated these contradictory

orders until the malt was removed and concealed, when the redoubtable Moll

loosed her grip, and the struggling, breathless gauger was only too glad to

escape.

The neatest smuggling story I know is one I read

somewhere. An officer came unexpectedly on a bothy, and on entering the

smuggler, who was sole occupant, calmly asked him, "Did any one see you

coming in?" "No," replied the officer. Seizing an axe, the smuggler said,

"Ah, then no one will see you going out!" The officer made a hurried exit.

When I was a boy there were stories, which I have not

been able to verify, of smuggling being carried on in the vaults and

dungeons of Urquhart Castle, which we youngsters were afraid to enter and

explore. Similar stories, and better founded perhaps, have been told about

Castle Campbell, the haunted Castle Gloom near Dollar. These and numerous

stories show over what an extensive area of Scotland, and in what diverse

places, smuggling was at one time prevalent.

Time would fail to tell how spirits, not bodies, have

been carried past officers in coffins and hearses, and even in bee-hives.

How bothies have been built underground, and the smoke sent up the house lum,

or how an ordinary pot has been placed in the orifice of an underground

bothy,

so as to make it appear that the fire and smoke were aye

for washing purposes. At the Falls of Orrin the bothy smoke was made to

blend judiciously with the spray of the falls so as to escape notice. Some

good tricks were played upon my predecessors on the West Coast. The Melvaig

smugglers openly diverted from a burn a small stream of water right over the

face of a high cliff underneath which there was a cave inaccessible by land,

and very seldom accessible by water. This was done to mislead the officers,

the cave being sea-washed, and unsuitable for distillation. While the

officers were breaking their hearts, and nearly their necks, to get into

this cave, the smugglers were quietly at work at a considerable distance. On

another occasion the Loch-Druing and Camustrolvaig smugglers were at work in

a cave near the latter place, when word reached them that the officers were

coming. Taking advantage of the notoriety of the Melvaig smugglers, a man

was sent immediately in front of the officers running at his hardest,

without coat or bonnet, in the direction of Melvaig, The ruse took, and the

officers were decoyed past the bothy towards Melvaig, the smugglers

meanwhile finishing off and removing their goods and utensils into safe

hiding.

After dinner, Tom Sheridan said in a confidential

undertone to his guests, "Now let us understand each other; are we to drink

like gentlemen or like brutes?" "Like gentlemen, of course," was the

indignant reply. "Then," rejoined Tom, "we shall all get jolly drunk, brutes

never do." A Glen-Urquhart bull once broke through this rule. There was a

bothy above Gartalie, where cattle used to be treated to draff and burnt

ale. The bull happened to visit the bothy in the absence of the smuggler,

shortly after a brewing had been completed, and drank copiously of the

fermenting worts. The poor brute could never be induced to go near the bothy

again. Tom Sheridan was not far wrong.