Alastair,

There

are quite a few references to Dr John Brown of Edinburgh and his great

short story ‘Rab and his Friends’ when one uses the ES Internal Search

Engine …. But the story itself does not seem to be anywhere on ES.

[Nor is it in The Book of Scottish Story that I

am currently OCR..ing]

Thus,

I have transcribed it for ES because I agree with Francis R. Packard M.D.,

when he wrote of the short story ''Rab and his Friends, in 1903,

"For simplicity, sincerity and obvious

truthfulness; for deep pathos and human sympathy; for pure humour and

insight into human nature, this little story is almost unexcelled."

I

attach here it, as usual in txt format Arial 10, with a jpeg of Dr Brown

to be inserted after the title on the web page …

Aye

yours,

John

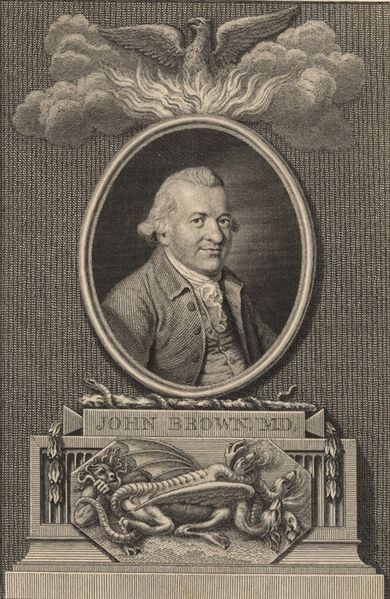

Dr John Brown

Author of ‘Rab and his Friends’

Dr John Brown (September 22, 1810 – May 11, 1882) was a Scottish

physician and essayist. He was the son of the clergyman John Brown

(1784–1858), and was born in Biggar, Scotland. He is best known for his

dog story, ‘Rab and his Friends’, of which it was said, “For simplicity,

sincerity and obvious truthfulness; for deep pathos and human sympathy;

for pure humour and insight into human nature, this little story is

almost unexcelled.”

Biography

He was educated at the High School and graduated as M.D. at the

University of Edinburgh in 1833, and practised as a physician in that

city. He was revered and beloved in no common degree, and he was the

cherished friend of many of his most distinguished contemporaries,

including Thackeray; his reputation, however, is based on the two

volumes of essays, Horae Subsecivae (Leisure Hours) (1858, 1861), John

Leech and Other Papers (1882), Rab and His Friends (1859), and Marjorie

Fleming: a Sketch (1863).

The first volume of Horae Subsecivae deals chiefly with the equipment

and duties of a physician, the second with subjects outside his

profession. He was emphatic in his belief that an author should publish

nothing unless he has something to say. Acting on this principle, he

published little himself, and only after subjecting it to the severest

criticism.

Brown wrote comparatively little; but all he did write is good, some of

it perfect, of its kind. In the mingling of tenderness and delicate

humour he has much in common with Lamb; in his insight into dog-nature

he is unique. He suffered during the latter years of his life from

pronounced attacks of melancholy.

Francis R. Packard M.D. wrote of the short story ''Rab and his Friends,

in 1903,

"For simplicity, sincerity and obvious truthfulness; for deep pathos and

human sympathy; for pure humour and insight into human nature, this

little story is almost unexcelled."

‘RAB AND HIS FRIENDS’

1859

By Dr. John Brown (1810-1882)

Four-and-thirty years ago, Bob Ainslie and I were coming up Infirmary

Street from the High School, our heads together, and our arms

intertwisted as only lovers and boys know how or why.

When we got to the top of the street and turned north we espied a crowd

at the Tron Church. "A dog-fight!" shouted Bob, and was off; and so was

I, both of us all but praying that it might not be over before we got

up! And is not this boy-nature, and human nature, too? And don't we all

wish a house on fire not to be out before we see it? Dogs like fighting;

old Isaac says they "delight" in it, and for the best of all reasons;

and boys are not cruel because they like to see the fight. They see

three of the great cardinal virtues of dog or man-courage, endurance,

and skill in intense action. This is very different from a love of

making dogs fight, and aggravating and making gain by their pluck. A

boy, be he ever so fond himself of fighting, if he be a good boy, hates

and despises all this, but he would have run off with Bob and me fast

enough; it is a natural, and a not wicked, interest that all boys and

men have in witnessing intense energy in action.

Does any curious and finely ignorant woman wish to know how Bob's eye at

a glance announced a dog-fight to his brain? He did not - he could not-

see the dogs fighting; it was a flash of an inference, a rapid

induction. The crowd round a couple of dogs fighting is a crowd

masculine mainly, with an occasional active, compassionate woman

fluttering wildly round the outside and using her tongue and her hands

freely upon the men, as so many "brutes"; it is a crowd annular,

compact, and mobile; a crowd centripetal, having its eyes and its heads

all bent downward and inward to one common focus.

Well, Bob and I are up, and find it is not over; a small thoroughbred,

white bull-terrier is busy throttling a large shepherd's dog,

unaccustomed to war but not to be trifled with. They are hard at it; the

scientific little fellow doing his work in great style, his pastoral

enemy fighting wildly, but with the sharpest of teeth and a great

courage. Science and breeding, however, soon had their own; the Game

Chicken, as the premature Bob called him, working his way up, took his

final grip of poor Yarrow's throat--and he lay gasping and done for. His

master, a brown, handsome, big, young shepherd from Tweedsmuir, would

have liked to have knocked down any man, would "drink up Esil, or eat a

crocodile," for that part, if he had a chance; it was no use kicking the

little dog; that would only make him hold the closer. Many were the

means shouted out in mouthfuls of the best possible ways of ending it.

"Water!" but there was none near, and many cried for it who might have

got it from the well at Blackfriar's Wynd. "Bite the tail!" and a large,

vague, benevolent, middle-aged man, more desirous than wise, with some

struggle got the bushy end of Yarrow's tail into his ample mouth and bit

it with all his might. This was more than enough for the much-enduring,

much-perspiring shepherd, who, with a gleam of joy over his broad

visage, delivered a terrific facer upon our large, vague, benevolent,

middle-aged friend, who went down like a shot.

Still the Chicken holds; death not far off. "Snuff! a pinch of snuff!"

observed a calm, highly dressed young buck with an eye-glass in his eye.

"Snuff, indeed!" growled the angry crowd, affronted and glaring. "Snuff!

a pinch of snuff!" again observes the buck, but with more urgency;

whereon were produced several open boxes, and from a mull which may have

been at Culloden he took a pinch, knelt down, and presented it to the

nose of the Chicken, The laws of physiology and of snuff take their

course; the Chicken sneezes, and Yarrow is free!

The young pastoral giant stalks off with Yarrow in his arms--comforting

him.

But the bull-terrier's blood is up, and his soul unsatisfied; he grips

the first dog he meets, and, discovering she is not a dog, in Homeric

phrase, he makes a brief sort of ‘amende’ and is off. The boys, with Bob

and me at their head, are after him: down Niddry Street he goes, bent on

mischief; up the Cowgate like an arrow - Bob and I, and our small men,

panting behind.

There, under the single arch of the South Bridge, is a huge mastiff,

sauntering down the middle of the causeway, as if with his hands in his

pockets; he is old, brindled, as big as a little Highland bull, and has

the Shakespearean dewlaps shaking as he goes.

The Chicken makes straight at him, and fastens on his throat. To our

astonishment, the great creature does nothing but stand still, hold

himself up, and roar - yes, roar, a long, serious, remonstrative roar.

How is this? Bob and I are up to them. He is muzzled! The bailies had

proclaimed a general muzzling, and his master, studying strength and

economy mainly, had encompassed his huge jaws in a home-made apparatus

constructed out of the leather of some ancient ‘breechin’. His mouth was

open as far as it could; his lips curled up in rage – a sort of terrible

grin; his teeth gleaming, ready, from out the darkness; the strap across

his mouth tense as a bowstring; his whole frame stiff with indignation

and surprise; his roar asking us all round, "Did you ever see the like

of this?" He looked a statue of anger and astonishment done in Aberdeen

granite.

We soon had a crowd; the Chicken held on. "A knife!" cried Bob; and a

cobbler gave him his knife; you know the kind of knife, worn obliquely

to a point and always keen. I put its edge to the tense leather; it ran

before it; and then! - one sudden jerk of that enormous head, a sort of

dirty mist about his mouth, no noise, and the bright and fierce little

fellow is dropped, limp and dead. A solemn pause; this was more than any

of us had bargained for. I turned the little fellow over, and saw he was

quite dead: the mastiff had taken him by the small of the back like a

rat and broken it.

He looked down at his victim appeased, ashamed, and amazed; sniffed him

all over, stared at him, and, taking a sudden thought, turned round and

trotted off. Bob took the dead dog up, and said, "John, we'll bury him

after tea." "Yes," said I, and was off after the mastiff. He made up the

Cowgate at a rapid swing; he had forgotten some engagement. He turned up

the Candlemaker Row, and stopped at the Harrow Inn.

There was a carrier's cart ready to start, and a keen, thin, impatient,

black-a-vised little man, his hand at his gray horse's head, looking

about angrily for something. "Rab, ye thief!" said he, aiming a kick at

my great friend, who drew cringing up, and, avoiding the heavy shoe with

more agility than dignity and watching his master's eye, slunk dismayed

under the cart--his ears down, and as much as he had of tail down, too.

What a man this must be - thought I - to whom my tremendous hero turns

tail! The carrier saw the muzzle hanging, cut and useless, from his

neck, and I eagerly told him the story, which Bob and I always thought,

and still think, Homer, or King David, or Sir Walter alone were worthy

to rehearse. The severe little man was mitigated, and condescended to

say, "Rab, ma man - puir Rabbie," whereupon the stump of a tail rose up,

the ears were cocked, the eyes filled and were comforted; the two

friends were reconciled. "Hupp!" and a stroke of the whip were given to

Jess, and off went the three.

Bob and I buried the Game Chicken that night (we had not much of a tea)

in the back-green of his house, in Melville Street, No. 17, with

considerable gravity and silence; and being at the time in the Iliad,

and, like all boys, Trojans, we of course called him Hector.

Six years have passed - a long time for a boy and a dog; Bob Ainslie is

off to the wars; I am a medical student, and clerk at Minto House

Hospital.

Rab I saw almost every week, on the Wednesday, and we had much pleasant

intimacy. I found the way to his heart by frequent scratching of his

huge head and an occasional bone. When I did not notice him he would

plant himself straight before me and stand wagging that bud of a tail,

and looking up, with his head a little to the one side. His master I

occasionally saw; he used to call me "Maister John," but was laconic as

any Spartan.

One fine October afternoon I was leaving the hospital, when I saw the

large gate open, and in walked Rab, with that great and easy saunter of

his. He looked as if taking possession of the place, like the Duke of

Wellington entering a subdued city, satiated with victory and peace.

After him came Jess, now white from age, with her cart; and in it a

woman carefully wrapped up - the carrier leading the horse anxiously and

looking back. When he saw me, James (for his name was James Noble) made

a curt and grotesque "boo," and said, "Maister John, this is the

mistress; she's got a trouble in her breest - some kind o' an income,

we're thinkin'."

By this time I saw the woman's face; she was sitting on a sack filled

with straw, with her husband's plaid round her, and his big-coat, with

its large, white metal buttons, over her feet.

I never saw a more unforgettable face--pale, serious, lonely, delicate,

sweet, without being at all what we call fine. She looked sixty, and had

on a mutch, white as snow, with its black ribbon; her silvery, smooth

hair setting off her dark-gray eyes - eyes such as one sees only twice

or thrice in a lifetime, full of suffering, full also of the overcoming

of it; her eyebrows black and delicate, and her mouth firm, patient, and

contented, which few mouths ever are.

As I have said, I never saw a more beautiful countenance, or one more

subdued to settled quiet. "Ailie," said James, "this is Maister John,

the young doctor; Rab's friend, ye ken. We often speak aboot you,

doctor." She smiled and made a movement, but said nothing, and prepared

to come down, putting her plaid aside and rising. Had Solomon, in all

his glory, been handing down the Queen of Sheba at his palace gate, he

could not have done it more daintily, more tenderly, more like a

gentleman than James, the Howland carrier, when he lifted down Ailie,

his wife. The contrast of his small, swarthy, weather-beaten, keen,

worldly face to hers - pale, subdued, and beautiful - was something

wonderful. Rab looked on concerned and puzzled, but ready for anything

that might turn up, were it to strangle the nurse, the porter, or even

me. Ailie and he seemed great friends.

"As I was sayin', she's got a kind o' trouble in her breest, doctor;

wull ye tak' a look at it?" We walked into the consulting-room, all

four; Rab, grim and comic, willing to be happy and confidential if cause

should be shown, willing also to be the reverse on the same terms. Ailie

sat down, undid her open gown and her lawn handkerchief round her neck,

and, without a word, showed me her right breast. I looked at it and

examined it carefully, she and James watching me, and Rab eying all

three. What could I say? There it was, that had once been so soft, so

shapely, so white, so gracious and bountiful, so "full of all blessed

condition," hard as a stone, a centre of horrid pain, making that pale

face, with its gray, lucid, reasonable eyes, and its sweet, resolved

mouth, express the full measure of suffering overcome. Why was that

gentle, modest, sweet woman, clean and lovable, condemned by God to bear

such a burden?

I got her away to bed. "May Rab and me bide?" said James. "You may; and

Rab, if he will behave himself." "I'se warrant he's do that, doctor."

And in slunk the faithful beast. There are no such dogs now. He belonged

to a lost tribe. As I have said, he was brindled, and gray like Rubislaw

granite; his hair short, hard, and close, like a lion's; his body

thick-set, like a little bull - a sort of compressed Hercules of a dog.

He must have been ninety pounds' weight, at the least; he had a large,

blunt head; his muzzle black as night; his mouth blacker than any night;

a tooth or two - being all he had - gleaming out of his jaws of

darkness. His head was scarred with the records of old wounds, a sort of

series of fields of battles all over it; one eye out, one ear cropped as

close as was Archbishop Leighton's father's; the remaining eye had the

power of two; and above it, and in constant communication with it, was a

tattered rag of an ear, which was forever unfurling itself, like an old

flag; and then that bud of a tail, about one inch long, if it could in

any sense be said to be long, being as broad as long - the mobility, the

instantaneousness of that bud were very funny and surprising, and its

expressive twinklings and winkings, the intercommunications between the

eye, the ear, and it, were of the oddest and swiftest.

Rab had the dignity and simplicity of great size; and, having fought his

way all along the road to absolute supremacy, he was as mighty in his

own line as Julius Caesar or the Duke of Wellington, and had the gravity

of all great fighters.

You must have often observed the likeness of certain men to certain

animals, and of certain dogs to men. Now, I never looked at Rab without

thinking of the great Baptist preacher, Andrew Fuller. The same large,

heavy, menacing, combative, sombre, honest countenance, the same deep,

inevitable eye; the same look, as of thunder asleep, but ready--neither

a dog nor a man to be trifled with.

Next day my master, the surgeon, examined Ailie. There could be no doubt

it must kill her, and soon. If it could be removed - it might never

return - it would give her speedy relief - she should have it done. She

curtsied, looked at James, and said, "When?" "To-morrow," said the kind

surgeon - a man of few words. She and James and Rab and I retired. I

noticed that he and she spoke little, but seemed to anticipate

everything in each other.

The following day, at noon, the students came in, hurrying up the great

stair. At the first landing-place, on a small, well-known blackboard,

was a bit of paper fastened by wafers, and many remains of old wafers

beside it. On the paper were the words:

"An operation to-day. J.B., Clerk ."

Up ran the youths, eager to secure good

places; in they crowded, full of interest and talk. "What's the case?"

"Which side is it?"

Don't think them heartless; they are neither better nor worse than you

or I; they get over their professional horrors, and into their proper

work; and in them pity, as an emotion, ending in itself or at best in

tears and a long-drawn breath, lessens, while pity, as a motive, is

quickened, and gains power and purpose. It is well for poor human nature

that it is so.

The operating-theatre is crowded; much talk and fun, and all the

cordiality and stir of youth. The surgeon with his staff of assistants

is there. In comes Ailie; one look at her quiets and abates the eager

students. That beautiful old woman is too much for them; they sit down,

and are dumb, and gaze at her. These rough boys feel the power of her

presence. She walks in quietly, but without haste; dressed in her mutch,

her neckerchief, her white dimity short-gown, her black bombazeen

petticoat, showing her white worsted stockings and her carpet shoes.

Behind her was James with Rab. James sat down in the distance, and took

that huge and noble head between his knees. Rab looked perplexed and

dangerous -forever cocking his ear and dropping it as fast.

Ailie stepped up on a seat, and laid herself on the table, as her friend

the surgeon told her; arranged herself, gave a rapid look at James, shut

her eyes, rested herself on me, and took my hand. The operation was at

once begun; it was necessarily slow; and chloroform -one of God's best

gifts to his suffering children – was then unknown. The surgeon did his

work. The pale face showed its pain, but was still and silent. Rab's

soul was working within him; he saw something strange was going on,

blood flowing from his mistress, and she suffering; his ragged ear was

up and importunate; he growled and gave now and then a sharp, impatient

yelp; he would have liked to have done something to that man. But James

had him firm, and gave him a glower from time to time, and an intimation

of a possible kick; all the better for James - it kept his eye and his

mind off Ailie.

It is over; she is dressed, steps gently and decently down from the

table, looks for James; then turning to the surgeon and the students,

she curtsies, and in a low, clear voice, begs their pardon if she has

behaved ill. The students - all of us - wept like children; the surgeon

wrapped her up carefully, and, resting on James and me, Ailie went to

her room, and Rab followed. We put her to bed. James took off his heavy

shoes, crammed with tackets, heel-capped and toe-capped, and put them

carefully under the table, saying: "Maister John, I'm for nane o' yer

strynge nurse bodies for Ailie. I'll be her nurse, and I'll gang aboot

on my stockin' soles as canny as pussy." And so he did; and handy and

clever, and swift and tender as any woman was that horny-handed, snell,

peremptory little man. Everything she got he gave her; he seldom slept;

and often I saw his small, shrewd eyes out of the darkness, fixed on

her. As before, they spoke little.

Rab behaved well, never moving, showing us how meek and gentle he could

be, and occasionally, in his sleep, letting us know that he was

demolishing some adversary. He took a walk with me every day, generally

to the Candlemaker Row; but he was sombre and mild; declined doing

battle, though some fit cases offered, and indeed submitted to sundry

indignities; and was always very ready to turn, and came faster back,

and trotted up the stair with much lightness, and went straight to that

door.

Jess, the mare, had been sent, with her weather-beaten cart, to Howgate,

and had doubtless her own dim and placid meditations and confusions on

the absence of her master and Rab and her unnatural freedom from the

road and her cart.

For some days Ailie did well. The wound healed "by the first intention";

for as James said, "Oor Ailie's skin's ower clean to beil." The students

came in quiet and anxious, and surrounded her bed. She said she liked to

see their young, honest faces. The surgeon dressed her, and spoke to her

in his own short, kind way, pitying her through his eyes, Rab and James

outside the circle - Rab being now reconciled, and even cordial, and

having made up his mind that as yet nobody required worrying, but, as

you may suppose, ‘semper paratus’.

So far well; but, four days after the operation, my patient had a sudden

and long shivering, a "groosin," as she called it. I saw her soon after;

her eyes were too bright, her cheek coloured; she was restless, and

ashamed of being so; the balance was lost; mischief had begun. On

looking at the wound, a blush of red told the secret; her pulse was

rapid, her breathing anxious and quick; she wasn't herself, as she said,

and was vexed at her restlessness. We tried what we could. James did

everything, was everywhere, never in the way, never out of it; Rab

subsided under the table into a dark place, and was motionless, all but

his eye, which followed every one. Ailie got worse; began to wander in

her mind, gently; was more demonstrative in her ways to James, rapid in

her questions, and sharp at times. He was vexed, and said, "She was

never that way afore, no, never." For a time she knew her head was

wrong, and was always asking our pardon - the dear, gentle old woman;

then delirium set in strong, without pause. Her brain gave way, and then

came that terrible spectacle,

"The intellectual power, through words and

things,

Went sounding on, a dim and perilous way";

she sang bits of old songs and Psalms,

stopping suddenly, mingling the Psalms of David and the diviner words of

his Son and Lord with homely odds and ends of ballads.

Nothing more touching, or in a sense more strangely beautiful, did I

ever witness. Her tremulous, rapid, affectionate, eager, Scots voice -

the swift, aimless, bewildered mind, the baffled utterance, the bright

and perilous eye; some wild words, some household cares, something for

James, the names of the dead, Rab called rapidly and in a "fremyt"

voice, and he starting up, surprised, and slinking off as if he were to

blame somehow, or had been dreaming he heard. Many eager questions and

beseechings which James and I could make nothing of, and on which she

seemed to set her all, and then sink back ununderstood. It was very sad,

but better than many things that are not called sad. James hovered

about, put out and miserable, but active and exact as ever; read to her,

when there was a lull, short bits from the Psalms, prose and metre,

chanting the latter in his own rude and serious way, showing great

knowledge of the fit words, bearing up like a man, and doating over her

as his "ain Ailie." "Ailie, ma woman!" "Ma ain bonnie wee dawtie!"

The end was drawing on; the golden bowl was breaking; the silver cord

was fast being loosed - that ‘animula, blandula, vagula, hospes,

comesque’, was about to flee. The body and the soul - companions for

sixty years - were being sundered and taking leave. She was walking,

alone, through the valley of that shadow into which one day we must all

enter - and yet she was not alone, for we know whose rod and staff were

comforting her.

One night she had fallen quiet, and, as we hoped, asleep; her eyes were

shut. We put down the gas, and sat watching her. Suddenly she sat up in

bed, and, taking a bedgown which was lying on it rolled up, she held it

eagerly to her breast - to the right side. We could see her eyes bright

with a surprising tenderness and joy, bending over this bundle of

clothes. She held it as a woman holds her sucking child; opening out her

night-gown impatiently, and holding it close and brooding over it and

murmuring foolish little words, as over one whom his mother comforteth,

and who sucks and is satisfied. It was pitiful and strange to see her

wasted, dying look, keen and yet vague- her immense love.

"Preserve me!" groaned James, giving way. And then she rocked back and

forward, as if to make it sleep, hushing it, and wasting on it her

infinite fondness. "Wae's me, doctor; I declare she's thinkin' it's that

bairn." "What bairn?" "The only bairn we ever had; our wee Mysie, and

she's in the Kingdom forty years and mair." It was plainly true; the

pain in the breast, telling its urgent story to a bewildered, ruined

brain, was misread and mistaken; it suggested to her the uneasiness of a

breast full of milk, and then the child; and so again once more they

were together, and she had her ain wee Mysie on her bosom.

This was the close. She sank rapidly; the delirium left her; but, as she

whispered, she was "clean silly"; it was the lightening before the final

darkness. After having for some time lain still, her eyes shut, she

said, "James!" He came close to her, and, lifting up her calm, clear,

beautiful eyes, she gave him a long look, turned to me kindly but

shortly, looked for Rab but could not see him, then turned to her

husband again, as if she would never leave off looking, shut her eyes,

and composed herself. She lay for some time breathing quick, and passed

away so gently that, when we thought she was gone, James, in his

old-fashioned way, held the mirror to her face. After a long pause, one

small spot of dimness was breathed out; it vanished away, and never

returned, leaving the blank, clear darkness without a stain.

"What is our life? It is

even as a vapour, which appeareth for a little time, and then vanisheth

away."

Rab all this time had been full awake and motionless; he came forward

beside us; Ailie's hand, which James had held, was hanging down; it was

soaked with his tears; Rab licked it all over carefully, looked at her,

and returned to his place under the table.

James and I sat, I don't know how long, but for some time. Saying

nothing, he started up abruptly, and with some noise went to the table,

and, putting his right fore and middle fingers each into a shoe, pulled

them out and put them on, breaking one of the leather latchets, and

muttering in anger, "I never did the like o' that afore!"

I believe he never did; nor after either. "Rab!" he said, roughly, and,

pointing with his thumb to the bottom of the bed. Rab leaped up and

settled himself, his head and eye to the dead face. "Maister John, ye'll

wait for me," said the carrier; and disappeared in the darkness,

thundering down-stairs in his heavy shoes. I ran to a front window;

there he was, already round the house and out at the gate, fleeing like

a shadow.

I was afraid about him, and yet not afraid; so I sat down beside Rab,

and, being wearied, fell asleep. I awoke from a sudden noise outside. It

was November, and there had been a heavy fall of snow. Rab was ‘in statu

quo’; he heard the noise, too, and plainly knew it, but never moved. I

looked out; and there, at the gate, in the dim morning – for the sun was

not up--was Jess and the cart, a cloud of steam rising from the old

mare. I did not see James; he was already at the door, and came up the

stairs and met me. It was less than three hours since he left, and he

must have posted out--who knows how? - to Howgate, full nine miles off,

yoked Jess, and driven her astonished into town. He had an armful of

blankets, and was streaming with perspiration. He nodded to me, and

spread out on the floor two pairs of clean old blankets having at their

corners, "A.G., 1794," in large letters in red worsted. These were the

initials of Alison Graeme, and James may have looked in at her from

without--himself unseen but not unthought of - when he was "wat, wat,

and weary," and, after having walked many a mile over the hills, may

have seen her sitting, while "a' the lave were sleeping," and by the

firelight working her name on the blankets for her ain James's bed.

He motioned Rab down, and, taking his wife in his arms, laid her in the

blankets, and happed her carefully and firmly up, leaving the face

uncovered; and then, lifting her, he nodded again sharply to me, and

with a resolved but utterly miserable face strode along the passage and

down-stairs, followed by Rab. I followed with a light; but he didn't

need it. I went out, holding stupidly the candle in my hand in the calm,

frosty air; we were soon at the gate. I could have helped him, but I saw

he was not to be meddled with, and he was strong, and did not need it.

He laid her down as tenderly, as safely, as he had lifted her out ten

days before--as tenderly as when he had her first in his arms when she

was only "A.G."--sorted her, leaving that beautiful sealed face open to

the heavens; and then, taking Jess by the head, he moved away. He did

not notice me, neither did Rab, who presided behind the cart.

I stood till they passed through the long shadow of the College and

turned up Nicolson Street. I heard the solitary cart sound through the

streets, and die away and come again; and I returned, thinking of that

company going up Libberton Brae, then along Roslin Muir, the morning

light touching the Pentlands, and making them like onlooking ghosts;

then down the hill through Auchindinny woods, past "haunted Woodhouselee";

and as daybreak came sweeping up the bleak Lammermuirs, and fell on his

own door, the company would stop, and James would take the key, and lift

Ailie up again, laying her on her own bed, and, having put Jess up,

would return with Rab and shut the door.

James buried his wife, with his neighbours mourning, Rab watching the

proceedings from a distance. It was snow, and that black, ragged hole

would look strange in the midst of the swelling, spotless cushion of

white. James looked after everything; then rather suddenly fell ill, and

took to bed; was insensible when the doctor came, and soon died. A sort

of low fever was prevailing in the village, and his want of sleep, his

exhaustion, and his misery made him apt to take it. The grave was not

difficult to reopen. A fresh fall of snow had again made all things

white and smooth; Rab once more looked on, and slunk home to the stable.

And what of Rab? I asked for him next week at the new carrier who got

the good-will of James's business and was now master of Jess and her

cart. "How's Rab?" He put me off, and said, rather rudely, "What's

‘your’ business wi' the dowg?" I was not to be so put off. "Where's Rab?"

He, getting confused and red, and intermeddling with his hair, said,

"'Deed, sir, Rab's deid." "Dead! What did he die of?" "Weel, sir," said

he, getting redder, "he didna' exactly dee; he was killed. I had to

brain him wi' a rack-pin; there was nae doin' wi' him. He lay in the

treviss wi' the mear, and wadna come oot. I tempit him wi' kail and

meat, but he wad tak naething, and keepit me frae feeding the beast, and

he was aye gurrin', and grup, gruppin' me by the legs. I was laith to

mak' awa' wi' the auld dowg, his like wasna atween this and Thornhill--but,

'deed, sir, I could do naething else." I believed him. Fit end for Rab,

quick and complete. His teeth and his friends gone, why should he keep

the peace and be civil?

He was buried in the braeface, near the burn, the children of the

village, his companions, who used to make very free with him and sit on

his ample stomach as he lay half asleep at the door in the sun, watching

the solemnity.

Recollections of Dr. John Brown

Author of 'Rah and His Friends,' etc. by Alexander Peddie (1894)

Rab

and His Friends

Spare Hours

First Series

Second Series

Third Series |