|

Our thanks to David Wilson for

letting us publish this on our site. Here is what he said when he

emailed about this...

"I recently put an out-of-copyright

book online, which I thought Electric

Scotland might be interested in. It's The Book of Saint Fittick,

which deals

with the history of St. Fittick's church, its locality; Torry,

Aberdeen, and

Scotland as a whole. Amongst other things, it contains excerpts

from

records, written in Middle Scots, folklore, and local accounts,

sometimes in Doric.

As well as having a long and fascinating religious and social

history, St.

Fittick's is also the place that William Wallace, or part of him

(the part

sent to this corner of Scotland), is said to be buried.

I would, of course, be making it available for free.... to a good

home :-) I

very much enjoy the Electric Scotland website and feel this book

is a

wonderful testimony to St. Fittick, the people of Torry and

Scotland. As

you'll see, if and when you read it, it's one of those wee old

books that

were a labour of love, written in almost poetic prose, yet giving

much

valuable and fascinating information.

I hope you'll enjoy it and will consider putting it on you

website, bringing

it, I hope, to a wider audience."

David Wilson

the_howlat@yahoo.co.uk |

This edition copyright

© 2003 Ogmios Press

and David Wilson

(all rights reserved) |

Here is an

Introduction to the Author from his book "Poems" (1911)

THOMAS WHITE OGILVIE

was born at Keith, Banffshire, on the 23rd January, 1861. His

parents were the late John Ogilvie, a highly respected merchant of

Keith, and his wife, Elizabeth White, daughter of John White,

farmer, Morayshire. There was a family of eight, of whom only two

now survive, the Rev. John Ogilvie, the Manse, Slains, and Mr.

Charles George Ogilvie of Delvine, Perthshire, and of Earlsmont,

Banffshire. Thomas was educated at the Public School, Keith, and

afterwards spent a few months in a law office there, but not being

enamoured of the law, he entered a local chemist’s shop. After a

brief sojourn there, he migrated to Aberdeen in 1876, and became an

apprentice to the well known firm of Davidson & Kay, chemists, where

he remained ten years, latterly as their principal assistant. He

then decided to graduate in medicine, and accordingly matriculated

at Aberdeen University.

His career at the

University was exceptionally brilliant, as may be seen from the

following record:—

First Bursar in

Medicine.

First Prizeman and Medallist in Zoology.

First Prizeman in Botany.

First Prizeman in Junior Anatomy.

First Prizeman in Senior Anatomy.

First Prizeman in Histology.

First Prizeman in Comparative Anatomy.

First Prizeman in Practical Chemistry.

He graduated M.B.,

C.M., with Honours, and during his undergraduateship, he occupied

the following important posts at his Alma Mater:—

University Extension

Lecturer in Biology.

Two years Demonstrator in Zoology, and

Prosector in Anatomy.

During his University

career he began the important work of the re-organization of the

Natural History Museum at Marischal College, and succeeded in

effecting many important improvements in this department, a work

which was much appreciated by the University authorities. As one of

the editorial committee of Alma Mater, he took his share in the

literary activities of that department of student life. In addition

to his University work, he successfully carried on evening classes

for teachers in such subjects as Botany and Natural History. His

abilities were undoubtedly of an exceptionally high order, and, as

will be obvious from the above, he was no ordinary student. He was,

in fact, what is sometimes called a many-sided man, and was

possessed of a personality the charm of which it is not easy to

over-estimate. Naturally his friends anticipated for him a brilliant

future. That these hopes were not fully realized must at once be

conceded, and this may be accounted for in a great measure by

indifferent health.

Long after our Author

had left the service of Messrs. Davidson & Kay, they wrote of him as

follows:—

“His business

capacity, scientific attainments and devotion to work and duty,

gained for him the confidence of employers and the respect and

esteem of everyone he came in contact with, and his brilliant

after-career at the University gave great pleasure to all his

friends.”

During the ten years’

service with that firm, he was an earnest worker in Natural History,

Botany, and kindred subjects, and many a happy hour did he spend

botanising on the Hill of Tullos, Scotston Moor, and such-like

places in the vicinity of the city. At the same time, he did not

neglect either his ordinary work or general literature. He was an

omnivorous reader, and was, in particular, passionately fond of

poetry and history. He did not confine himself to the great or

better known writers, but loved to search out gems of poesy from the

minor poets. It was indeed the enthusiasm he displayed in this

delightful department of literature that first drew our attention to

the value of the minor poets, a lesson which we have never

forgotten. We well remember one evening, in the upper room of

Davidson & Kay’s, reading with him the chapter in that deeply

interesting volume of Hill Burton’s “The Book-Hunter,” titled “Some

Book Club Men.” When we came to the description of some of the fine

songs of Sir Alexander

Boswell, such as,

“Jenny’s Bawbee," “Guid Nicht and joy be we ye a’,” and “Jenny dang

the Weaver,” the expression of delight that flashed across his

intellectual face, and the intense interest with which he followed

the extracts from “Skeldon Haughs, or the Sow is flitted,” remain to

this day imprinted on our memory. The next night we met, he had

obtained a copy of and was quite familiar with Boswell’s poems. The

above anecdote may appear trifling, but it is illustrative of the

enthusiasm and energy which he threw into all he did, and of his

usual occupations in his spare time. He was either deeply engrossed

with “Darwin” or “Huxley”; working with a microscope; classifying

botanical specimens; or, with a congenial friend, studying some of

the masterpieces of literature.

Ogilvie’s subsequent

professional career may be briefly told. Immediately after

graduation, he accepted an appointment as Medical Officer to the

Rubies and Sapphires of Siam, Ltd., and, while in Siam, his devotion

to duty and to the interests of his employers, at a time of great

trial, earned for him the highest commendations; but the strain was

too much for his not over-robust frame. He was prostrated with

malarial fever, and had to be carried through the jungle to Bangkok.

At one time he was dropped in the jungle by the native bearers and

left to his fate, but he was, fortunately, near a Buddhist temple,

to which he was able to crawl, and a priest there, gave him the

succour he needed. Soon afterwards, the bearers, somewhat afraid for

the consequences of their cruel desertion, returned, and taking

leave of his kind friend the Buddhist priest, he arrived at Bangkok

more dead than alive. He returned to this country in shattered

health, and although he exhibited all his old intellectual alertness

and enthusiasm, his health was never so good after that unfortunate

experience. When it is added, that he lost the most of his personal

and medical belongings during that terrible journey through the

jungle, and that the Company was unable— in consequence, mainly, of

the occupation by the French of the territory within its sphere of

influence—to implement its obligations to him, it can readily be

understood that he was injured not only in health but in pocket.

A two years’ spell of

fairly easy work at Longhope, Orkney, somewhat restored his health,

and on the suggestion of a friend, Dr. Ogilvie came to Aberdeen in

1895, and commenced practice in Torry, then a small but rapidly

rising suburb.

Little need be said

of the seven years during which he practised in Torry, as the events

in the life of an ordinary medical practitioner, in a working-class

locality, do not usually present features for stirring narrative. He

threw himself into his work with characteristic energy, and in that

brief period, by dint of sheer hard work, he not only built up a

large and lucrative practice and made himself prominent in the

public life of the locality, but also established a reputation as a

writer of elegant verse, as a versatile lecturer, and as a raconteur

of no mean order. It was during this time that the most and the best

of his poems were written, and they appeared in Brown's Book-Stall,

Bon-Accord, and the evening press of the city. Though those engaged

in public life invariably make enemies as well as friends, Dr.

Ogilvie had the art, and that in no ordinary degree, of making

friends, and we believe that his enemies, if any, were few and far

between. When, therefore, in 1902, he decided, mainly on account of

his health, to leave this country for South Africa, the efforts that

were made by the people of Torry to retain his services, and the

expressions of regret that his departure evoked, were too widespread

and spontaneous amongst all classes of the community, to be other

than sincere. His public work had already been formally recognized

by his being made a Justice of the Peace for the County of the City

of Aberdeen. A brief sojourn in Kimberley; three years in practice

at Gringley-on-the-Hill, near Doncaster; an attempt to establish a

new home in British Columbia, which failed in consequence of another

collapse in health; then about a year of hard work as a locum in

London, bring us near the end. In 1908 he purchased a practice at

Willesden, North London. On the 17th October he took possession of

the practice and house, and on the following morning he was found

dead. The ill health from which he had suffered more or less for

years, had, notwithstanding his indomitable courage, told on his

somewhat enfeebled body, and hastened the end. So at the early age

of forty-eight, and when just about to enter on what promised to be

a congenial sphere of usefulness, died one of the staunchest of

friends and most kindly and loveable of men, leaving behind him a

widow with five young sons, and also a memory that will long be

cherished by all who had the good fortune to own his friendship.

As yet, little has

been said of our Author as a writer of verse. That he was a keen

lover of nature goes without saying. One has but to read some of the

pieces written when still a youth, to appreciate at once that from

boyhood, nature had claimed him for her own. In fact, nature in her

varying moods was the dominating note of his life, and is the

dominating note of the best of his poems, and these will doubtless

have a charm for most readers: but the strong sense of humour which

permeates some, and which made him so ideal a companion, will

undoubtedly appeal to others. That he was a charming lecturer many

audiences knew well, but that he had the gift of poesy was known to

only a small number even of his friends. This is accounted for by

the fact that he usually wrote over the initials “T. W. O.,” varied

occasionally by “O. W. T.”; latterly adopting the French numeral

“Deux”—a play upon his initials—as a noom-de-plume, and by that he

was known as a writer. We do not feel justified, even if qualified,

to enter on either an appreciative, an analytical, or a critical

survey of his poetry, but we venture to say that one who was

capable, at the age of sixteen, of writing “Art and Nature,” “Autumn

in the Duthie Park,” and “Tullos Hill,” and again to produce

“Anxious,” “Saint Fittick’s,” and “Waiting for the Nightingale”—in

all of which there is expressed, so exquisitely, such a variety of

feeling—could, given the opportunity and the leisure, have written

much more of a quality of which any writer might well be proud. The

charming ode “ The Bards of Bon-Accord ” (with the capital portraits

of William Carnie and William Cadenhead by Mr. William Smith, Jun.),

was, like the ode to Cadenhead himself, written on the impulse of

the moment, and we have the best of reasons for knowing how much

both bards appreciated the compliment paid them by their young

compeer.

We should not omit to

mention the “Book of Saint Fittick,” a history of Torry, written and

presented as a Bazaar Book to Saint Fittick’s Church, Torry, in

December, 1901. This book was profusely illustrated with drawings by

the following local artists:—Messrs. George Davidson (now deceased),

J. A. H. Hector, Stephen Reid, and William Smith, Jun. An excellent

sketch of the proposed Well of Saint Fittick was also contributed by

Mr. William Kelly, architect, and pity ’tis that the well, as

designed, was not erected. This was his last public service to the

district, and in that delightful volume he has made live again, with

all their quaint and curious customs, the fisher folk of the

long-forgotten past. We do not profess that it possesses absolute

historical accuracy. It could hardly do so, written as it was at

high pressure and in the midst of so busy a life, but we do claim

for it literary ability and taste, in both prose and verse. One has

but to read the verses at the beginning of each chapter, in

imitation of Sir Walter Scott’s quotations from old authors, to see

that Ogilvie had in him the gift of true poetry. Although we have

only referred to poetry, it should in justice be added, that Dr.

Ogilvie made occasional contributions of short stories to the press,

and these were in no way inferior to his poems.

A well-known local

journalist (U.U. S.), writing of our Author after his death, said:

“While in Aberdeen Dr. Ogilvie was a frequent and valued

contributor, both in prose and verse, to the local press. His

writings— one and all—displayed great literary grace and poetic

fervour and imagination, and withal, he had a rare gift of

spontaneous humour. For several years nearly every monthly issue of

Brozun’s Book-Stall contained something from his pen, over the

signature of ‘Deux.’ He was a ripe scholar in the true sense of that

term, and his books to him were full of living friends with whom he

could not only pass the time, but so to say, ‘pass the time o’ day ’

as with an everyday acquaintance, as exemplified in his dream-poem,

‘Storylanders.’ Dr. Ogilvie’s most complete work was ‘The Book of

Saint Fittick.’ It was a gathering together, as the Author puts it,

of some fragments of history relating to the Torry district, and

what is inseparable from it, the harbour and river-mouth. To this

work the doctor’s many young artistic friends lent a willing helping

hand, and the volume is enriched with between thirty and forty

pictures and plates of the district. It is an ideal work in every

respect, and its success was immediate and phenomenal, and

fortunate, indeed, is the collector who possesses a copy. A kindlier

soul, or one more richly endowed with the graces that make

friendship valued and enduring, never ‘passed out from the crowd.’”

The task of

collecting, and the process of selecting the poems suitable for

publication from amongst many that were of a semi-private nature,

have been to us a pleasure, although in many respects a somewhat sad

one. Memories of the past seem to jostle each other as one reads the

lines, and although it may well be that in our affection for Thomas

White Ogilvie we may be accused of over-rating the literary value of

his writings, yet we presume to believe that many of his poems will

rank as among the best that have been given to Aberdeen by her

honoured list of minor poets; that they will stand both comparison

and the test of time; and that readers will heartily endorse our

opinion, that in presenting this volume to the public, we are only

doing justice to the talents of one who was a distinguished graduate

of our University, and who, although a Banffshire “loon” by birth,

is, we believe, well worthy of a place amongst the Bards of

Bon-Accord.

D. S.

Aberdeen, October, 1911.

Here is a sample

Poem...

A Ballad

THE GOLFER AND THE BRICKLAYER

by Thomas White Ogilvie M.B., C.M. (1861-1908) of Aberdeen, Scotland

[This ballad first appeared in Brown's Book-Stall, Aberdeen, in

April, 1899.]

Jim Jolly was sound in both body and mind,

But his friends have their doubts if he still is;

Some subtle infection, 'tis perfectly plain.

Has scattered the germs in his blood or his brain

Of the Golfi-gum-gutty Bacillus.

Jim J. is a townsman of credit and weight,

Quite a model of sensible bearing,

But now when he's mentioned there's noddings and winks

Since this direful zymotic he caught on the Links,

And is bent on the red jacket wearing.

One Saturday morning, quite innocentlie,

Jim went down to see what the game was,

He saw a white ball on the tip of a "tee,"

Then a swing and a swish and afar o'er the lea

Like the flight of a swallow the same was.

Away over bent and away over sand,

Over hazard and whinbush and bunker,

Jim followed that ball over acres of land

As it skimmed, skipped, or soared from a lofting shot grand.

And he reckoned the game was a clinker.

Then Encyclopedias of sport having got.

And a " Badminton " sought for to borrow.

He longed for the morning to practise the shot,

Resolving at daybreak to be on the spot—

But it rained cats and dogs on the morrow.

Of expense quite regardless he gathered the tools

In a slender bag brand-new and brown.

And the weather still raining he read up each rule.

Too proud he to go with a caddy to school.

And he spoke golf all over the town.

He learnedly talked of his mashie and cleek,

He knew all the points of a putter,

Where the niblick was strong, where the driver was weak.

And the best build and brand of a brassie to seek,

And all technical terms he could utter.

But day after day the barometer fell.

And the weather got wetter and wetter.

Till Jim wished the clerk of the weather in ----well ;

He was dying to golf, could you honestly tell

That your words had been wiser or better?

But Jim J. must die of this fever or "swing,"

So he cleared out the chairs and the table,

And into the parlour his driver did bring.

And he tethered a ball to a bundle and string,

And hit it as hard as he's able.

When that curious game on the carpet was done,

Of the holes made he rarely has spoken ;

His first in the mirror he got with a "one,"

Then two in the window he had with a run.

And a bust with this record was broken.

Mistress Jolly thought golf such a beautiful game,

No sport she was sure could be finer;

But withering sarcastic she spoke all the same,

When she said that if often to such " tees " he came,

He would make some good holes in her china.

Next morning at daybreak Jim went to the green

At the back, where his wife dries and bleaches,

With the ball and the bundle all smiling serene,

The rummiest golfer that ever was seen,

In a smoking-cap, braces, and breeches.

Just over the way on a neighbouring feu

A tenement mansion was rising.

And up and down ladders there went one or two

Of the workmen with bricks on their heads, quite a few.

All balanced with skill most surprising.

Jim studied his grip and he practised the swing,

Oft foosled the ball, sometimes hit it,

When the gutty would fly to the end of its string,

And Jim with the air of a golfer would sing

As he strode up the green to get it.

Replaced on the tip of a conical tee,

Jim touched his left ear with the whipping.

Then swinging his driver right vigorouslie,

Got the ball by a fluke just as clean as could be,

Broke the string, and away it went skipping.

Like a ball from the mouth of a musket it sped,

As it passed on its path parabolic.

But a blind hazard came in the shape of a head

With bricks on the top, and with hair just as red.

And a tongue with a speech diabolic.

Like a hundred of bricks that dozen came down.

Some language was mixed with the clatter,

And that bricklayer's face wore a terrible frown.

As he clenched up a ponderous fist hard and brown,

While blandly Jim asked "What's the matter?"

There were compliments passed which I will not repeat,

In that conference over the wall,

But a modus vivendi was found in a treat

For the mason consisting of whisky and meat.

And for Jim—he recovered his ball.

You can download a

copy of his book "Poems"

in pdf format here

PREFACE

SAINT FITTICK, the

ruins of whose church stand by the mouth of the "Cheerful Vale of

Tullos," was the Patron Saint of Torry. The "Book of St. Fittick" is a

gathering together of some fragments of history relating to the Torry

district and what is inseparable from it—the harbour and the river

mouth.

The writer of this

sketch makes no claim to be a historian of the district, or to have

made any original research on the subject; but as a lover of this

river mouth, and craggy shore, and hill-girt hollow, he has strung

together such items of local interest as he may have gleaned in

reading our local literature or picked up in converstation with old

inhabitants.

Such a subject bristles

with controversial points—these are not discussed here; the writer has

tried to make only such statements as are supported by respectable

authorities.

The name of the Patron

Saint illustrates the difficulties the historian of Torry has to

encounter. S. Mofutacus, S. Monfutacus, Sanct Mofette, Sanct Musset,

Sant Mufott, S. Futtack, San Fittick, St. Fiacre, S. Fotinus, S.

Fithack, S. Fittick, and—Blessed Thistle!—Sandy Fittick, are some of

the numerous aliases of this much mis-spelt Saint. What interest the

narrative lacks, it is hoped the illustrations will supply.

T.W.O.

OLD KIRK OF ST.

FITTICK

THE KIRK

Out from the city's boom

and flare,

Dim-eyed and dazed the soul in me,

I wearied seek for thought and prayer

The lonely church beside the sea.

|

N a quiet hollow, brown

and green and golden as the seasons of verdure pass, within the reach

of the sea-foam, blown landwards when a south-easter fills the bay

with crescents of surging white, stands the old church of St. Fittick;

roofless are the walls within which the voice of living man has long

ceased to plead and to urge, but within and without are gathered the

worshippers of old; the clamour of the bell, still musically sonorous

from its quaint belfry, rouses them no longer, their last sin is

committed, the final word of grace is spoken, and in the silence they

wait till the dawn of a last day breaks on yonder bay that frets and

murmurs at the hollow's mouth, as it murmured in their ears in the

quiet Sabbaths of yore, when their psalms mingled with the eternal

chant of the sea—of that sea which itself is a graveyard to their

people, for the lives of the dwellers by the shore, whose work is on

the waters, are wrapped in an atmosphere of tragedy; their traditions

are of wrecks, and the events of their lives are dated from disasters.

Six and a half

centuries have come and gone since, with all the imposing ceremonial

of the Church of Rome, Bishop David de Bernham dedicated this little

church, and part of the walls now standing are believed to have been

raised by the masons of those early thirteenth century days ere Bruce

had arisen to fight for the crown, and Wallace for the independence of

their country. For over three hundred years the priests of the Church

of Rome ministered within its walls. Then came the Reformation, when,

what came to be considered the superstitious rites and blasphemous

claims of the priests were swept away, and another worship guided the

lives of the people who gathered to their devotions in the Tullos

valley. For a century and a half after the Reformation, Bishops and

their kindred ruled over the Church of St. Fittick, until early in the

eighteenth century Richard Maitland, the last Episcopal minister of

Nigg, whose initials are seen to this day cut on the sandstone of the

belfry, was deposed for praying for James, called the Pretender, in

those wild days when the standard of rebellion was raised on the Braes

of Mar, in the fruitless struggle that ended at Culloden. Since that

day in July, 1716, Presbyterian clergy ministered in the old church to

the spiritual needs of the people of Nigg, until 1829, when St.

Fittick was abandoned to the dead and the people gathered under that

picturesque tower, seen, from the old churchyard, standing out against

the western sky from among the dark firs of Tullos and Kincorth. Well

has it served and serves, but the river is spanned and the city grows

on its southern bank, and a new St. Fittick's arise to share in the

guidance Godwards.

' Tis a sweet little

old ruin this old church with its simple but finely proportioned

lines, its sharp east gable surmounted by the quaint belfry in which

hangs a bell still rung at funerals "Sabata pango, Funra plango,"—"Sabbaths

I proclaim, at Funerals I toll,"—says the legend on the bell. This

bell was made by John Mowatt, and Old Aberdeen blacksmith, who had

learnt the craft and mystery of bell-founding from the French

bell-maker, Gelly, who, half a century before, sojourned several years

in the Old Town, casting and re-casting many of the city bells. It is

now over 140 years since it was hung in the little steeple, and many a

curious crowd of red-cloaked and snowy-mutched woman it has drawn in

the old days from the villages on the cliffs, from Downies and

Burnbanks and Cove.

Time has obliterated

many an old inscription and relic from church and graveyard, which

might have recalled the habits and interests of the old dwellers by

the mouth of Dee and Tullos hill and hollow, but there yet remain some

vestiges on the walls which are eloquent of beliefs that have faded

and of customs that are extinct. By the open doorway, in the south

wall, hang a few rusted links of chain, all that remains of the

ancient jougs in which the scolds, the story-tellers and other minor

offenders were fastened up at the church door to do penance in sight

of the congregation, as it passed into worship. The ecclesiastical

tribunals of the days when the jougs held their culprit, inflicted

many a punishment which, if wholesome and necessary then, have long

since been condemned and fallen into disuse. "Expose in sackcloth on

the high and low stools of repentence in the church, imprisonment in

the steeple and the noisome dungeon under the vestry, flogging at a

stake after conviction and sometimes before it, ducking in the river,

pillorying in the public streets, carting through the town with a

crown of paper," and many another curious infliction not likely to be

revived, although the offences still linger with us.

There were lepers in

the Tullos Valley in the days when the priests swung the censers in

the church of St. Fittick. Outcast and miserable, they might not

mingle with the people as they worshipped, but in the church wall,

within sight and hearing of the priest, there was a little oblong

opening, through which, himself unseen, the leper could join in the

service. On the north wall, near the ground, we can to-day see this

"Leper's Window," and over against it on the south wall the doorway,

now built up, by which the priest approached the altar. Rich and poor

suffered from this loathsome disease, and in Aberdeen there was a

"Lepers' House" in the vicinity of our present Nelson Street, and

certain curious provisions were made for their maintainance, such as

that every load of peats that came to town had to yield up one peat to

the lepers.

The old Baptismal Font

of the church is now preserved in Marischal College. Could some old

priest who blessed and banned in the days when holy water filled this

great rude bowl, but know its history since his reverent congregation

crossed themselves before it, how might he cry with Hamlet

"To what base uses we may return."

For, until rescued from its degradation by its

present custodian, it served for many years as the trough in a poultry

yard.

From among the many clergy who have ministered in

old St. Fittick's Church there is one character who stands out

prominently in the traditions of the parish. This is James Farquhar,

the first Presbyterian minister in Nigg. He was a man of unusual

physical strength, and on account of this qualification he was

frequently employed to preach churches vacant on the deposition of the

Episcopalian when that duty was accompanied by no little personal

danger, for many a congregation resisted the separation from their old

pastors.

On one occassion on going to preach vacant the

parish of Lochlea in Forfarshire, Mr. Farquhar learned that there was

a very vigorous opposition to the proposed change, and it was likely

that a serious attempt would be made to prevent him carrying out the

instructions of the Presbytery. Dressed as a farmer, wearing a big

round bonnet and carrying a substantial stick, he approached the

church and mingled with the crowd, discussing with the intimate

knowledge of his apparent class the crops and the weather. The

appointed hour passed and the crowd became impatient. At last Farquhar

said, "There's little sign o' ony minister comin', would you hae ony

objections tae my gi'ein you a word." "O, nane ava," came the ready

response. Up rose James, and, mounting the pulpit, preached the church

vacant before the dumbfounded congregation.

On the occasion when he entered on his duty at St.

Fittick's he found two Episcopalian partisans pummelling the bellman,

who had ventured to ring in the first Presbyterian service. Laying his

powerful hands on the aggressors, he knocked their heads together and

stood by till the bellman finished, and then led the way to the

church.

His tongue seems to have been as direct and as

vigorous as his fist. Once a "dandy" dressed in a red-coloured vest,

embroidered with lace, made some disturbance in St. Fittick's during

the prayer. "O Lord, if it be thy holy will, hew down that scarlet-breistit

sinner wi' the gryte gully o' they gospel," thundered his reverence,

and then concluded his prayer in peace. Such a markedly popular and

plain-spoken personality would have enemies, of course. He was called

John Gilon, for nickname, and there still lingers two lines of some

forgotten lampoon

"John Gilone, the great horse leech,

When he came first to Nigg to preach."

In the "Rabblers Rabbled" of William Meston, the

poet, sometime Professor of Philosophy at Marischal College, we find a

reference to the feats of Mr. Farquhar in connection with another

Presbyterian worthy

....in Whig Kirk planting,

Where people's inclination's wanting,

And there he mighty feats had done

In company with John Gilon.

Such memorials of the dead as may have existed

before the Reformation have long since crumbled into dust, but in the

churchyard, near the S.E. corner of the church, there is a flat stone

with an inscription which vividly recalls the turbulent days of civil

war, when that military genius, "Montrose", leading the troops of the

King against the Covenanters of Aberdeen, defeated them, and let loose

his Irish mercenaries on the town, who sacked it, running mad in the

streets, plundering and slaying without distinction and without mercy.

Spalding, the local chronicler of the troublous times of the Covenant,

tells a vivid story of the fight which began at the "Twa Mile Cross."

"There was little slaughter in the fight, but

horrible was the slaughter in the fight fleeing back to town, which

was our townsmen's destruction; whereas, if they had fled and not come

near the town, they might have been in better security, but being

commanded by Patrick Lesly, provost, to take to the town, they were

undone. Yet himself and the prime Covenanters being on horseback, ran

away safely: The lieutenant follows the chase into Aberdeen, his men

hewing and cutting all manner of men they could overtake within the

town, upon the streets, or in their houses, or round about the town as

our men were flying, with broad swords, without mercy or remead. Thir

cruel Irishes, seeing a man well clad, would first tirr him, to save

his clothes unspoiled, syne kill the man.... Montrose returned to the

camp this samen Friday at night leaving the Irishes killing, robbing,

and plundering this town at their pleasure, and nothing was heard but

pitiful howling, crying, and weeping, and mourning through all the

streets."

|

WILLIAM MILNE'S

TOMBSTONE |

Under the flat stone at the S.E. corner of St.

Fittick's Churchyard lies one of the victims of "thir Irishes," the

inscription, which is in Latin, is thus rendered in "Jervise's

Epitaph's" : "William Milne tenant of Kincorth, slain by his enemies

on 10th July, 1645, for the cause of Christ, here rests in peace from

his labours, whom piety, probity, and God's Holy Covenant made happy,

fell by the sword of a savage Irishman—I am turned to ashes."

|

THE WATCHER'S HOUSE |

In the N.E. corner of the kirkyard stands the

"Watcher's House," erected in the days when the seekers after medical

knowledge were struggling for the good of humanity against the

obstacles raised by its own prejudices and distrust, and when this

lonely chuchyard was often pillaged of its newly buried dead by the

body-snatchers or "resurrectionists" to supply Marischal College with

material for dissection. When the Dee was diverted into its present

channel in 1874, on trenching the garden ground beside "Jessie

Petrie's Inn"—the foundations and part of the garden wall of which are

still standing at the foot of Ferry Road—two skeletons were found, and

tradition in the village tells how the body-snatchers, caught at their

gruesome toil, were pursued to the river, and being unable to cross

without detection, hid the bodies behind the inn, and were never able

to recover them again. Better days are with us, and now no

sacrilegious hand disturbs the bones that moulder in this "Auld

Kirkyard," where it is believed that not even a worm, man's last bosom

friend, may enter. A local tradition tells how a portion of the sacred

soil was carried from Ireland after St. Patrick had banished the worms

and snakes. Since when no worm has ever been found in the holy

precincts of St. Fittick.

THE WELL

And find where sea winds

lift the foam,

And stir the larch on Tullos hill,

As in the saintly days of Rome,

The Holy Well has healing still.

|

THE JOUGS. |

y the brink of the bay, not far from the old

church, there is another monument crusted with old associations and

traditions. In advancing from one form of religious belief to another,

there is a tendency among men to mingle with the higher and purer

worship they have attained some trace of the superstitions they have

abandoned. The golden calf is raised by the Israelites while their

leader is in the presence of Jehovah, and pagan rites creep into the

observances of the early Christians.

St. Fittick's spring still drips its mite of water

into the great sea, and it dripped and dribbled when the Old Aberdeen

blacksmith hung his bell in the belfry yonder. It still soaks through

the turf among the eyebright and sea-daisies as when, over 600 years

ago, it quenched the thirst of the masons labouring at the foundations

of the church, and it flows to-day as cool and clear, if not so

voluminous, as when the warriors of old were piling cairns on the

Tullos Hill over the bodies of their dead chiefs, ere the name of

Christ had penetrated the Grampian hills, or men dreamt of raising

temples to his name in the Tullos hollow. But the broad lawn of green

sward, which streched between the well and the bay, has been, in

recent years swept away by the encroachment of the sea.

Far back in the dark days of pagan worship each

spring by woodland and sea-shore had its peculiar spirit, believed to

have some control over human destinies and to be propitiated by rites

and sacrifices, and so ceremonies were performed by the wells and

offerings were left on their banks. When Christianity penetrated among

a rude people—prone to superstition—the saint supplanted the pagan

diety, but often the pagan rite was continued and the intercession of

the saint sought by the old offerings.

|

THE LADY WELL. |

St. Fittick's Well was in great repute in the days

before the Reformation frowned on such superstitious observances, and

long afterwards in spite in ordinance and infliction by the powers

spiritual and temporal. Down, even till within the memory of people

still living, the Well was frequented on account of its healing

powers, and people gathered from country and town to lay down their

simple offerings—a rag, a nail, a pin—and to seek some benefit. By

degrees the religious significance of the rite was lost, but the

custom of visiting the well continued, and on the first Sunday of May

great numbers of people, chiefly from the city, visited the spring and

the neighbourhood, and gave themselves up to amusement and revel on

beach and sea brae. Town Council and Kirk Session struggled by laws

and punishments to stop those Sunday wanderings and to efface those

vestiges of old superstitions, but the customs of centuries die hard,

and to-day young and old, to whom the name St. Fittick is a

meaningless term and the repute of his well quite unknown, ramble on

Sunday's and week-days to the bay once called by his name, and they

find the old power still lingers, for the beauty of the Bay, the fresh

sea-breeze, and the pure draught from the old spring still bless and

heal.

On the wayside bank to the east of the old church

there is another well, known of old as the Lady Well,

"Cooled a long time in the deep

delved earth"

roofed with an old Saxon vault, and reached by a

short flight of time-worn stone steps. It is a quaint and interesting

spring, but tradition has brought down little knowledge concerning it.

A little way south from St. Fittick's Well, or the Downies Well, as it

is also called, stands the great detached mass of cliff called " The

Downies Craig,' united to the mainland by a narrow neck, " The Brig o'

ae Hair," and shewing a curious perforation in the neighbouring cliff,

well named " The Needle E'e.' The Downies Craig is closely linked in

history with St. Fittick's Well. The Craig was the usual limit of the

wanderings of the May Day revellers. Here they crossed the "Brig o' ae

Hair," very different in those days from its present state, for the

slenderness of the connecting neck, which gave it its graphic name has

been in great part massed by the rubbish, tilted over it, when the

adjacent railway cutting was made. On the summit of the Craig there is

a stretch of fine green sward, and thereon, the brig crossed, the

youthful revellers used to cut the names of their loves.

The Craig, to the North and South of the narrow

"Brig," descends sheer to the water, a mighty pendicular wall of

gnarled and twisted gneiss. It forms with the landward cliffs a

profound chasm, and and narrow, into which in storm, the wtaer is

driven with terrific force and deafening turmoil. Eatswards to the sea

the Craig descends gradually, with mighty boulders, grey-green with

sea lichen and hacked and fissured by the tempests of many thousand

winters. Here is the haunt of the hooded crow, wariest of birds, which

perches on the inaccessible pinnacles and rears its brood in the

spray-dank hollows. There are many caves in the cliffs here, sought in

olden times by far other wanderers than May Day revellers. In the year

1640, the ranks of the army of the Covenant were filled by many a

forced recruit from the streets of Aberdeen. In this year we read that

"seven score burgesses, craftsmen and their servants were seized and

forcibly sent off to join Leslie's army for the invasion of England,

and many others, to escape the same fate, fled the city and sought

shelter about the craig of Downies and the recesses of the

neighbouring rocks."

The Old Burgh and Session Records of Aberdeen again

and again shew the paternal anxiety of minister and magistrate to

check the pilgrimages to the south side of the Dee, for, once the

religious meaning of the journey had passed away from the minds of the

people. it tended to degenerate into an opportunity for revel and

excess, and the solemn reflective quiet of the Sabbath, which the

God-fearing Fathers of the City anxiously sought to foster, was

seriously disturbed by the liberties claimed by the devotees of St.

Fittick.

The fishermen of Footdee did not object to this

popular crossing of the water; it was a lucrative custom for them, but

they were often fined and censured for hiring their boats on Sunday

and watching men were also stationed at the ferry boat to note such

persons as crossed the water to Torry, and order them before the

Session for reprimand and fine. A few extracts from the old records

will illustrate this state of matters three hundred years ago.

On the 8th May, 1603, "The said day it is thocht

expedient that ane baillie with twa of the Sessioun pass thro' the

toun everie Sabbath day, and nott sic as they find absent frae the

sermones, ather afoir or efternone, and for that effect that they pas

and serche sic houses as they think maist meit, and pass athort the

streits, and chiefly that now, during the symmer seasoun, they attend,

or cause ane attend at the ferrie boat and nott the names of sic as

gang to Downie that they may be punishit conforme to the act set doun

against the brackairs of the Sabbath."

On 1st June, 1606, four men are fined "Ilk ane o'

them in forty pence, to be payed to the puir for thair passing over

the water to Downie on Sunday last the tyme of the efternones sermon."

In 1616 there is the following municipal enactment.

"Gif ony man, womane, barne, or servand, sal be aprehendit in ony time

comin', going in the nicht, either be land or sie, to Downie, Sanct

Fittatk's Wall, or uther wyis vaiging idillie to ony superstitious

place, the persone being maister or mistress of a familie, their sones

and dochteris, sall pay furtie schillings of onlaw, totes quoties; and

the servants twenty schillings; and the maisters to be comptabill and

anserable for their wyffis, bairnies, and servandis."

Again, on the 28th Nov., 1630. "The said Margaret

Davidson, spous to Andrew Adam, was adjudjet in ane unlaw of fyve

pounds to be payed to the Collection, for directing her nurish with

her bairne thairin for recoverie of her health, and the said Margaret

and her nurish were ordaint to acknowledge thair offence befoir the

Sessione for thair fault and for laving ane offering in the well.

"The samen day it was ordaint be the haill Session

in ane voce that whatsomever inhabitant within this burgh wis found

going to Sant Fiacker's Well in ane superstitious manner for seeking

health to thameselffs or bairnes shall be censured in penaltie and

repentance."

"The belief in the Well gradually waned, but there

are still people living who remember some instances of the old rite.

One old woman in Torry, approaching her century of life, to whom the

writer of this sketch appealed for some reminiscence of her early

days, brightened up at the mention of St. Fittick's Well, the dull

eyes gleamed for a little, as a flash of recognition lit up the worn

old face. "I mind fine it was Jessie ____'s bairn, a thrivin' lassikie

till it got amo' its teeth, an' sine it dwined and dwined and naething

did it ony guid. I dinna ken fa' put it in Jessie's heid, but ae

meenlicht nicht she cut twa sheaves o' breid and put them in her

breist, and took the bairnie and gaed awa' tae the wallie at the Bay

o' Nigg, and she weish the bairnie in the wall, and syne she laid doon

the breid tae the fairies and cam' awa hame, and fae that day the

bairinie threeve and there are bairns o' that bairn in Torry the day."

Once started, this old lady gave many a glimpse of the customs and

superstitions of the Torry of a hundred years ago. "We hid ither wyes

o' curin' bairns and fouk fin I wis a lassie. I mysel' was the last

wife in Torry to cure a bairn wi' unspoken water. There wis a burnie

ca'ed the Struak ran doon oot o' far the Brickworks cam to be, past

Jessie Petrie's public-house by the waterside. The bairnie was wastin'

awa' till a shadow, an' it couldna eat an' it wouldna sleep, but just

murnt and murnt, an' its mither was sure the fairies had got at it. So

ae nicht I took a sma' pailie an' put a shillin' in't, and gaed awa'

to the stroopy at the top o' the Struak an' let the water fae the

stroopy run on the shillin', and if it turned heads up the trouble was

in the bairn's head, but if it turned tails up it was in its system,

but comin' or gaun I spak' tae naebody—for that's waht mak's unspoken

water. I met twa or three lassies I kent an' they cried to me, but I

said naething, and I met a lad I kent richt well, but I didna speak

tae him; and I got hame and weish the bairn wi' the unspoken water and

it got better. Did ye iver hear o' three times roon the crook?" she

continued. "I min' on the wives i' my mither's hoose daein' that, when

I was a bairn. They took three roon stanes fae the Bay o' Nigg, an

they ca'ed ane the heid, anither they ca'ed the heart, and the ither

ane wis the body, and they put them in the red fire, and the first

stane that crackit was the pairt the trouble was in, and then the

unweel body was carried three times roon the crook o' the big lum wi'

the unwell pairt held next to the crook, an sometimes they got better

an' sometimes they didna, jist the same as wi' the doctors noo-a-days."

THE BAY

And men may joy and men

may moan,

And generations come and go;

Eternal croons the undertone

Of tireless tides that ebb and flow.

This bay has borne other names than that familiar

to us. Saint Fiacre is the old name of the patron saint of this

district. Tradition says he was the son of Eugenius IV., an old Scotch

king of doubtful existence. The saint, leaving his native country,

retired to a hermitage on the Continent, where he died in 648, and was

buried in the Cathedral of Meaux, in France. The Bay is called after

him in many ways. St. Fittick's Bay, the common modern form of his

name, is derived from Ma Fithatk, the Celtic form of St. Fiacre; by

corruption the name Sanct Moffat's Bay is sometimes met with; while in

one old chart in the possession of Mr. Barnett, the delineator makes a

thoroughbred Scotchman of the old Saint, and calls it Sandy Fittick's

Bay.

It is a pretty place, this sheltered bight in the

rugged coast line, with its fine bend of foam-frilled water and its

beach of great smooth pebbles clattering incessantly in the ebb and

flow, pent in to the north by the bold peninsula of the Girdleness

with its lighthouse, and to the south by the low broken headland of

Greg's Ness. Interesting at all times is this little bay—in calm, when

the waters heave smoothly like a bosom in sleep,

And for hours upon hours,

As a thrall she remains,

Spellbound as with flowers,

And content in their chains,

And her loud steeds fret not, and lift not a lock of their deep

white manes.

- in storm, when the breakers surge shorewards

great curving masses of dazzling white, and roar on the pebbles

At the watchword's change,

When the wind's notes shift,

And the skies grow strange,

And the white squalls drift

Up sharp from the sea-line, vexing the sea till the low clouds lift;

but most beautiful when the moon hangs low over the

sea, and a gleaming path opens out from the Bay, across the open water

beyond, and ships pass from dark to dark across the shimmering way,

and on the shore the old church is transfigured in the soft light,

while tinkling musically the castanets of the water-stirred pebbles

rattle by the verge,

On the south side of the Bay, by the old Well, the

shore is a precipitous bank rapidly crumbling away. The path along the

top of this bank is yearly retreating inland, and the old paths which

but a few years ago were safe, now end abruptly at the cliff's brink.

The old Well of the Saint, alas! is on this brink

of destruction, and another winter of fierce south-easters may

overwhelm it. About two years ago the spring was traced back a few

yards from the brink, and a temporary well, with the spring only

partially tapped, built at a safe distance from the sea, but we hope

the day is not far distant when a monument, worthy of its hoary

traditions and its fine situation, will present the cooling stream of

the old spring to the pilgrims who to-day are seeking health and

repose by the Bay of Nigg, for St. Fittick's shore is still a

favourite haunt of the townspeople, and on summer afternoons the

cheery kettle bubbles on a dozen rude hearths raised on the

sea-sward—innocent altars to the Goddess Hygeia.

There is a tradition that a stronghold called "

Wallace Castle " once stood on the north side of the Bay. There is now

no trace of it, and it is likely that this name was applied to the

ruins of one of the watch-houses which stood here. Immense quantities

of stone setts for paving the London streets used to be shipped at the

Bay of Nigg. These were prepared at the quarries in the parish, which,

when opened about 1770, used to give employment to 600 or 700 men. The

rounded oblong pebbles of this shore were also largely used as

cobble-stones, and were shipped in large quantities from the Bay.

|

BRIDGE OF NIGG. |

There were in the old days other industries by the

Bay that brought a livelihood to the people in the neighbourhood.

There may still be seen on the north side, beside the hatcheries, the

foundation of the buildings of the old salt pans, where salt was made

from the sea water, and there are living in Torry to-day old people

who worked there. Here, also, the manufacture of kelp was a lucrative

trade. The tangle and seaware were gathered at low tide, and, after

being dried in the sun, were burned in heaps on the shore. The ashes

were the kelp, very valuable for the alkalies it yielded. Dr. Cruden,

who ministered over a hundred years ago in the old St. Fittick's

Church, informs us that in one year, 33 women and an overseer were

employed at the kelp-burning in the Bay, and that 11 tons of a very

fine quality were produced, kelp, at this time, being worth about £20

a ton, but the discovery of cheaper sources of the alkalies have long

since rendered the business unremunerative. It took the seaweed three

years to grow again to that maturity which made it fit for kelp

production. Old Jessie—recalls " the string o' cairts " she " minds

windin' awa' the wye o' the Brig o' Dee wi' the last load o' kelp fae

the Bye o' Nigg."

A stream that drains the Tullos hollow enters the

Bay about the middle of its bend. The Bay side road crosses the burn

by a little bridge called the Bridge of Nigg, from which, ere the

railway embankment intercepted the view, it was said one could see

further up Deeside than from any neighbouring point. Funeral

processions from the villages along the cliffs to St. Fitticks

Churchyard used to halt on the bridge, and, doffing their hats, the

bearers would mop their brows. They did this because it was the

custom, but the tired mourners little knew that this simple ceremony

dated from the Roman Catholic days when an image of the Virgin stood

by the bridge, to which the passers-by would uncover as they crossed.

But the shore of the Bay itself is much changed within a generation.

One who played by the old well when it was a simple spring issuing

from a broad grassy bank now swept away, says, "How different the Bay

looked when I was a boy. It was pure sand from the old salt pans round

almost to the bothy, and fine small gravel higher up, which we used to

get carted for our garden walks, and in those days of wooden ships

there was mostly some wreckage drawn up on the beach. I remember going

out in the salmon-fishers' cobbles, and looking over the edge to the

pure clean bottom. How it has all changed since the stones were taken

away to make the South Breakwater."

WRECKS

Here laughs and lures

the silken sea,

And widely clasps the hill-born wave;

And croons in lulling mockery

A cradle song above a grave.

ETWEEN the Girdleness and the river mouth there is

the Greyhope Bay, memorable as the scene of the most disasterous

shipwreck ever recorded in our local annals. "On the morning of the

1st of April, 1813, five whaling vessels were riding at anchor in the

roads when a sudden tempest came on from the S.E. Two of the ships

weighed and stood out to sea; but as part of the crew of one, the

ill-fated "Oscar," had been left ashore, she was obliged to put about

and keep near the land. By the time that all her men were on board she

was far inshore. Meantime the wind had died away, and from the heavy

roll of the sea, and a strong tide setting in, she was unable to clear

the Girdleness. Soon after the gale sprang up with increased violence;

it was accompanied with a dense shower of snow, and now blew from the

N.E. The vessel in vain endeavoured to ride it out; and after dragging

her anchor she was driven ashore in the Greyhope on a large reef. The

tremendous sea which broke over her threatened instant destruction,

and the only hope of safety for the crew was that of effecting a

communication with the land. For this purpose the mainmast was hewed

down in such a manner as that it might fall towards the beach; but it

dropped alongside the vessel. A number of the seamen who had clung to

the rigging were hurled into the sea along with it, many were swept

from the deck, and others who attempted to swim to the land were borne

down by the floating wreck or overwhelmed by the fury of the surf.

Only the forecastle now remained above water, and for a short time the

master and three sailors were observed upon it, imploring that

assistance which none could give. Of a crew of forty-four men only two

were saved." The bodies recovered from the sea were laid in one long

grave at the east end of St. Fittick Churchyard. Old folks still

living in Torry recall the figure of a broken old woman wandering

among the fisher huts and seeking alms at their doors. Her "all" went

down in the "Oscar," which carried her husband and three sons, and the

poor fisher folk who had seen them done to death, almost within arm's

length of help, never refuse to share their crust with the lone woman.

GREYHOPE.

Many another good ship has perished on the jags

which lie pitiless as sharks' teeth under the waves that lap the rocks

from Greg's Ness to the mouth of the river. One of the earliest local

wrecks of which we know recalls, in its elements of poetic justic, the

doom of Ralph the Rover, who perished on the crag from which he had

previously stolen the warning bell. Three hundred and forty years ago

a band of religious zealots marched from the south to Aberdeen;

maddened by the too palpable luxury, vice, and superstitious

observances of the priests, they were inspired by a wild desire to

sweep away every vestige of idolatry from the places of worship. Their

frenzy ever increasing as they advanced, their minds were at last

dominated by a mad desire for destruction, indescriminate and

unreasoning. Like the contagion of a plague, the frenzy fastened on

the lower classes in the town, and a wild rabble attacked the

religious houses in the city, sacking and spoiling as they went. They

even sought to drag the steeple of St. Nicholas Church to the ground.

but other citizens more sane resisted, and it was saved for that time.

Away they rushed to the Old Town, and the Cathedral was over-run by

the mad crowd. Everything that was beautiful, everything that was

breakable, everything that was worth lifting, was defaced, broken or

stolen. They tore the lead from the roof and the bells from the

steeple, and but for the timely arrival of the Earl of Huntly with

troops a broken wall might have been all left us of the goodly church

of St. Machar. But the jagged reefs of the Girdleness lay in wait for

some of the spoilers. One master robber, loading a ship with the

spoils of the church of the twin spires, the lead from the roof, and

the bells, set sail for Holland. But a storm arose and swept him on

the Girdleness, and, within sight of the church he had robbed, and in

the waters across which, in the quiet Sabbath evenings so often stole

the tolling of the Cathedral bells, the robber went down with those

bells he had for ever silenced, and weighted with the lead of the

church he had desecrated.

In 1637 the river Dee came down in spate, and drove

from their moorings by the Torry shore four vessels, one of which

contained a body of troops. A south-easterly gale was blowing which,

catching the vessels as they were swept across the bar, drove them on

the sands. The soldiers on the troop-ship were asleep when it struck,

lying on heather in the ship's bottom. Awakened by the shock and the

sea pouring in upon them in the darkness, a terrible scene ensued; a

struggle for life with the pitiless sea, and, in the panic of the

moment, their equally pitiless comrades. " Four score and twelve," the

old record tells us, "were wanting, or drowned, or got away."

But the river claims its victims as well as the

ocean. A summer rarely passes but some young life pays tribute to the

Dee. The crowning disaster on the river happened on the 5th April,

1876, when the ferry boat, on its journey to the Torry shore,

overturned with a load of seventy-three passengers, thirty-two of whom

were drowned.

It was the afternoon of a Sacramental fast-day. For

years these days, set apart for religious observance, had been

changing their character and had come to be largely spent as holidays,

and crowds of pleasure-seekers left the city to seek a change in the

woods and glens and by the sea shore. Torry had been from time

immemorial a favourite haunt of the townspeople, and on this day many

hundreds had crossed the river and wandered to St. Fittick's, the

Downies, and Tullos Hill. As the afternoon advanced the crowds seeking

the ferry became more numerous and more impatient. About three o'clock

over seventy passengers crowded into the boat before all its freight

from the south shore had been able to disembark. One poor girl, who

had just crossed from Torry, was obliged to return with the doomed

boat, and she was among the drowned. The boat, propelled by a wheel

round which a steel rope fixed on each bank worked, set out on its

fateful journey. The gunwales of the over-loaded craft were within an

inch or two of the water; the tide was ebbing ; the river, swollen by

the snows melting on its upper reaches, was in flood, and the boat was

swept down stream until the rope, stretched to its utmost limit,

formed a sharp bight beyond which the boat found itself unable to

advance. Tilting to the west side, the water began to flow in. The

passengers, who till now had been quiet and orderly, became panic-striken.

Many lept from the boat and saved themselves; but with the intention

of relieving the boat the rope was slackened at the north end. The

boat swept down, the rope tightened again and snapped, and at the same

moment the boat turned keel upwards and thirty-two of the

seventy-three passengers were drowned.

THE FERRY.

And so on down the years comes again and again the

great storm, when the sea rises, and roars, and swallows the ship and

its crew, and then the calm comes and the sea smiles and prattles with

the pebbles and fondles the seaweeds, and the loiterer by the summer

shore hears tell of wrecks that have been, but the sea is insatiable

and the by-and-by will rise up again in its fury, and claim more

victims. Many a wandering sailor, tossed dead and sea-chafed on beach

and in rock pool, sleeps in the churchyard of St. Fittick's by the

Bay, laid reverently there by the fisher folk who reck not how soon

that sea which yields them a livelihood may claim the life it

supports.

THE CAPSTAN.

TULLOS VALE

No fortress guards the

little vale,

Between the ocean and the Dee,

A church its castle on the hill,

A church its bulwark by the sea.

T is full of quiet charm, this little glen, with

its kirk on the height and its kirk in the hollow, extending from the

great gap in the cliff, which forms the Bay, up to the river, where,

with majestic bend, it sweeps glittering and gurgling by Allenvale and

Duthie Park, sweetest of resting places for the quick and the dead.

The valley is hemmed in to the south by that rigged ridge which Parson

Gordon, two and a half centuries ago, quaintly called the Grangebeen

Hills, and familiar to the city urchin to-day as " The Gramps," or

Tullos Hill. A miniature mountain chain in itself, studded with

hillocks which are its outliers, and cairns which are its peaks, and

for tarns and lochs the little water-filled hollows choked with water

sedge and cinquefoil, and carpeted around their swampy margins with

the green and crimson plush of bogmoss and sundew, a carpet spangled

with the orange stars of the bog asphodel, and beyond that the heather

and whin, blazing in bloom of gold in spring, dark green, and purple

in the fall, whilst a strip of woodland

"That just divides the desert from

the sown"

|

THE OLD KIRK

ROAD. |

yields a succession of greens throughout the year.

For there, while the snow still covers the distant Mount Battock and

Lochnagar, seen white from this hillside, the dainty tassels of the

larch swing out in the spring winds sprinkled with the rubies of the

young cones ; then comes the darker birch, and last of all, along the

old hill kirk road, the beech unfolds its fragile leaves, most

brilliant of woodland greens, and over all looms the gloomy fir as

surly to the touch of spring as it is sullenly unyielding to the

season of frost and tempest. Tullos Hill was planted in 1799. The

trees flourish along its northern border, but have almost disappeared

from the rest of the hill. The access to it is by an old road entering

the hill east of Tullos House by the beech row, but soon lost in whin

and bramble; one branch of it used to go straight south over the hill

to join the road to the coast, the other turned to the right, and

winding westwards, by the elf hillock, led to the Church of Nigg. What

is left of this old kirk road is now as waterworn and rugged as the

dry bed of a torrent, and bordered with a tangle of rasp and rose,

bramble and honeysuckle. Near by, where it used to wind westwards,

there are some curious circular trenches long hidden among

impenetrable whin, but revealed by recent hill fires. Immediately

behind Tullos House, on the borders of the wood there is the curious

mound known as the Elf Hillock, now covered sparsely with trees. This

is doubtless a place of sepulture. To the west of the hillock there is

a little crossing, long called " The Fairies' Briggie," for the keener

fancies of our forbears saw here a fit meeting-place for the children

of the moonlight, the local representatives of Oberon and Titania, and

Puck, and many another merry elf. Joseph Robertson conjectures that

our Elf Hillock may have been the scene of a fine ballad given by

Scott in his Minstrelsy of the Border, and reproduced in this book.

Beyond the strip of woodland, the hill on its

western half is chiefly covered by dense whin, which springs up

rapidly, and year by year is still more rapidly destroyed by the

frequent fires which careless folk kindle on the hill. From the old

road as it enters the hill a path winds up to a great cairn of stones

set on the sky-line; this is the Baron's Cairn. The stones are now

scattered about by many a young vandal, but formerly they were laid

down with care and regularity. It was at this cairn the beacons were

lit to warn the warders at the harbour that an enemies' ship

approached, in order that the river mouth might be closed by the great

boom, and that the block-house cannoniers stand to their guns. The

foundations of the watchman's house are to be seen close by the

Baron's Cairn. Further west there is another great pile, "The Cat's

Cairn," also on the sky-line, and at the east end of the hill a

smaller cairn stands, " The Crab's Cairn," while on the northern face,

N.E. of the Baron's Cairn, and far below the sky line, there is a huge

stone heap known as the "Tullos Cairn." These cairns were probably

intended to be commemorative of great events in the sturm und drang of

the fierce old days. The monuments remain, characters of a lost

tongue, the signification of which we cannot decipher. The cairns were

of great importance to the old navigators, and we find the most

precise directions given for employing them as guides and landmarks,

but it is very unlikely that they were originally piled up for this

purpose any more than were the twin spires of Old Machar Cathedral,

which were also taken as leading points by sailors. Between the Tullos

and Crab Cairns there is a hill-well, far removed from all source of

contamination, called Jacob's Well, a rillet from which soaks through

a little valley, among the bog moss and pennywort and sedge, to

collect in a neighbouring hollow as a broad reedy pool. Along the

course of this water trickle a kind of rush known as "sprots'' grows a

fine annual crop; these werel argely used for "raips" and thatching.

The harvesting of the sprots used to exercise to the utmost the

ingenuity and "slimness" of the farmers of Nigg. The sprots are

useless until mature, so the neighbouring agriculturalists kept a

jealous eye on their growth, each man resolving to reap those sprots

for himself as soon as they were ready. Mr. X. and his men stole out

one moonlight night and with stealthy scythe cleared the little hollow

and set the sprots up in stooks, to carry home at day dawn. Home they

returned in the night, hugging themselves in satisfaction at their

strategy, and after a brief sleep returned with daylight for their

hill harvest. But Mr, XX., a rival sprot seeker, who slept while they

reaped, had risen an hour earlier to cut the much coveted rushes, and,

finding them ready stocked to his hands, gathered them up in

thankfulness of his neighbour's industry.

CRAIGINCHES WOODED BANK.

The "Cheerful Vale of Tullos," as it is called in

an old survey, is the subject of a persistent tradition that once upon

a time the Dee flowed there. Another tradition has it that a Dutchman

long ago offered to lead the Dee down this way, and still more firm is

the current belief that it will yet seek the sea in the Bay of Nigg,

when

"Doon Tullos haugh, 'mang biggins

braw

Rolls in her royal course the Dee,

And lingering, limpid, silent, slow,

From Allenvale seeks to the sea."

But no longer is the Tullos hollow the undisturbed

retreat of farmer and fisherman. It is now the main artery of

communication between north and south and daily and nightly there

thunders along the erstwhile quiet valley train after train in quick

succession, laden with men and merchandise from the south and carrying

the produce of the fertile fields that stretch northwards from the Dee

and Don, and the sea harverst gathered by the famous fishing fleet of

Aberdeen.

ELF HILLOCK.

From the Baron's Cairn we no longer scan the sea

for the men of war of our "auld enemies of England," nor for the

hostile cruisers of France. Old Mrs. Greig, who lived into our day,

would tell how she once saw, from the watchman's house by the cairn,

during the great war with Napoleon, a French privateer chasing a

British ship along the coast and firing on her, but to-day the

prospect is peace, or but the warring of the elements when the sea is

vexed and the firs roar on the hill.

"When the wind, the grand old Harper,

Smites his thunder harp of pine."

From the old watch-house by the cairn a glorious panorama is spread

out, South and East and North and West. Eastward the brown heath meets

the blue sea, and beyond that sea and yet more sea, until the blue is

the blue of the sky. Away to the North,

"Gazing north we see the water that

grows iron round the pole,

From the shore that hath no shore beyond it set in all the sea."

on its peninsula the Girdleness Lighthouse lifts

its beacon, and from the high ground there, now "The Torry Park," a

prospect of sea shore of wonderful extent presents itself. Professor

Masson, writing of this part of the coast in 1871 said: "I think I

have never seen anywhere else so vast an arch of open sea. Eastward

you gaze. Not an island or a headland interrupts the monotony of

waters to the far sky-line; and you know that beyond that sky-line you

might sail and sail, still without interruption till you reached

Denmark or Norway."

You cannot see the Deemouth from the Cairn, but

Futty is there by the water's edge, and thence, like a great bow, the

yellow sands of Aberdeen Bay sweep northwards in a curve that might be

the mould of a rainbow. Banked with bent and frilled with breakers,

the beach stretches by Donmouth, the Black Dog, and Belhelvie, with

its line of Coastguard houses set white and black on the yellow

ground, until it slips from sight where sea-shore and sky meet, and

where, when night falls, the lights of Buchanness are seen to flash

and fade in the darkness. From the hollow by the shore rise the spires

and towers of the white city, ever steadily creeping over the fields

northwards and westwards. The Deeside Valley leads up to the distant

hills from which, on a clear day, stand out the splendid masses of

Mount Keen and Lochnagar, and overhead, as evening falls o'er Tullos

Hill, the sea-mews are hoarsely calling as they seek the cliffs after

a day's foraging on land, when

"Sail on sail along the sealine fades

and flashes here on land,

Flash and fade the wheeling wings on wings of mews that plunge

and scream."

THE OLD ESTUARY

Where yester day the

field were ploughed,

And cattle strayed, and trees were green,

To-day, in dinsome streets, a crowd

Of bustling city folks is seen.

ULLOS hollow is enclosed to the north by the high

ground extending westwards from the Torry Park, parallel with the

river, and ending in the pretty wooded bank that stoops abruptly to

the river's brink by the Suspension Bridge. On the northern slope of

this ridge, where but yesterday stood a decaying farm-house with its

"green mantled pool," overhung by old willow trees, there stands

to-day a new town, with spacious streets, high buildings, and a

bustling traffic; a transformation as rapid and complete as if, but

lately, the wonderful Lamp of Alladin had been rubbed up in Old Torry

Farm.

There were fisher folks in Torry, as surely as

there were fish in the bay, long ere Aberdeen had houses enough to

make a street, and long ere centuries of making, and buying, and

selling, and eager learning had evolved that level-headed race known

to the world as Aberdonians. In fancy we may conjure up the scene that

presented itself to the prehistoric Torryman, as he returned to his

hut by the mouth of Dee, after a day of limpet-gathering about

Girdleness, by way of the shoulder of the hill we now call the

Greyhope road.

ABERDEEN HARBOUR—1661,

1867, 1901

The dotted lines in the

middle figure indicate the last diversion of the river.

The tide is full, and the sun is seeking the

western hills that loom up beyond the land where the river comes from,

untraversed by the fisher folk, and full of fierce, roving tribes, the

echo of whose feuds and battles reach the dwellers by the river mouth

but rarely. From the Torry shore a vast sheet of water spreads

northwards and westwards : the lands we now know as the Links and

Footdee are not yet above the sea, which laps the base of the

Castlehill, entirely covering that space now occupied by the low-lying

streets between its base and the Quay, Virginia Street, James Street,

Commerce Street, etc.; it reaches the foot of St. Katharine's Hill, up

which the Shiprow now winds and Market Street ascends. There is sea

over the site of the station to the base of the steep ground that

descends from Crown Terrace to the level of the Denburn, where now the

railway is laid, and it stretches a narrow arm over the site of Dee

Village, along the gorge between Ferryhill and Springbank Terrace to

expand beyond into the Loch of Dee. The river, emerging from the

forests and marshes of lower Deeside, enters this broad estuary at the

Craiglug, where now the Suspension Bridge spans the river.

From the northern shore of this inland sea a series

of forest-clad hills and marshy hollows stretch away to where Brimond

fills the sky-line, with many a brook winding through the bog and

among the eminences destined to be the site of that fair city, which

yet sleeps bound in the granite heart of the hills, for the iron is

not yet forged for that magician's wand — the chisel — at whose touch

the rocks will open, and the white city will bourgeon like a flower.

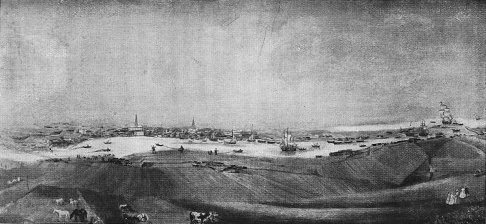

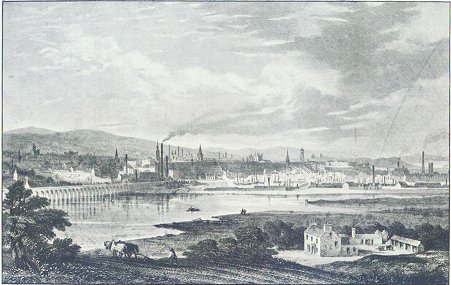

TORRY IN 1756.

From the picture by

Mossman.

Such is the scene we fancy ere written records aid

us, told by the flint weapons, the human bones, the gathered shells,