|

PREFACE

THE very kind reception

given to this collection by the Press has emboldened the Editor to allow

it to be republished. There are other very excellent collections of

Highland Music and Songs, but as this book contains several melodies not

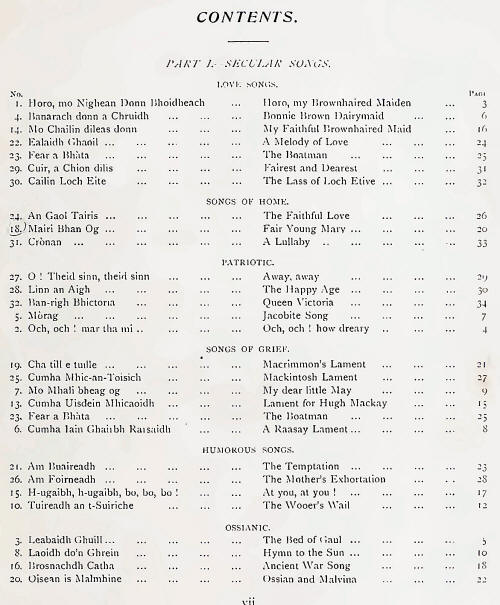

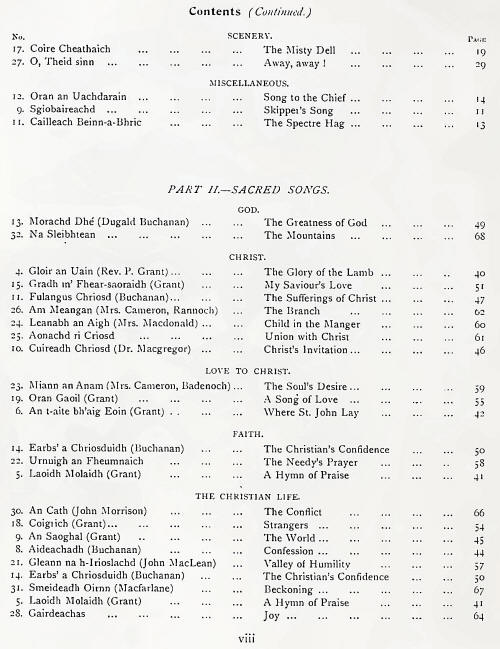

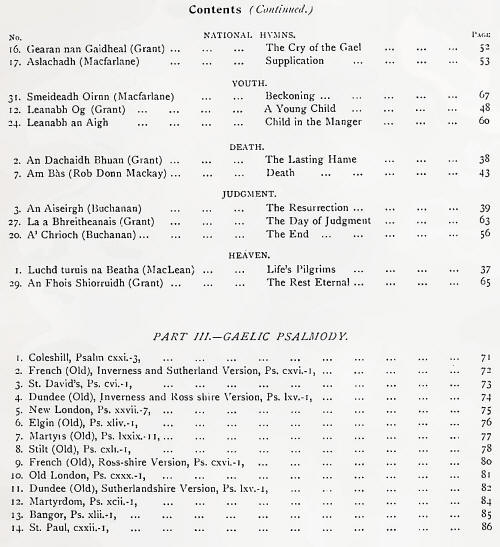

printed elsewhere (for example, Nos. 3, 8, 16, and 31 of Part I., and

Nos. 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,

28, 29, and 32 of Part 11. and as there is as yet no other collection of

Highland Sacred Music, it is perhaps not desirable that the book should

remain out of print. Cordial thanks are here tendered to the many

friends who have kindly assisted in collecting or revising either tunes

or chords.

HIGHLAND SONGS, HYMNS, AND MUSIC

THE Songs of the Scottish Highlands form a literary

heritage that will well repay study. They are remarkably rich in the

lighter graces of poetry—endless variety of metrical form, and opulence

of rhyme, and melodies that are both striking and sweet. Their

characteristic beauties and their limitations are perhaps both alike due

to their being so intensely native. The feelings expressed are simple,

and scenery and incidents are redolent of the Highlands. At a period

when the popular songs of other countries were stilted and artificial,

the songs of the North were natural and true. English versifiers might

affect longings after the myrtle groves and artificial poses of classic

times, but the Gaelic bards delineated with loving art the beauties of

the mountain landscapes, and the deep, simple emotions of Highland

hearts.

The Love of Nature in all her moods is indeed the deepest

characteristic of Highland song, which in this anticipated the loftier

flights of Burns and Wordsworth. A good example of Duncan Ban

Macintyre’s appreciation of Nature will be found in No. 17 of this

collection, “Coire Cheathaich,” and it pervades the muse of his

contemporary, Alexander Macdonald, whose praise of the moorland heather

is worth translating—

The bonny, clinging, clustering

Dear heather growing slenderly,

With snowy honey lustering

And tassels hanging tenderly;

In pink and brownish proud array,

With springy flexibility,

With scented wig all powdery,

To keep up its gentility.

In more dignified strain we have the ode to the sun by

Ossian, or some unknown bard—

Thou movest in thy might alone,

For who hath power to travel near?

The ageless oak shall yet fall prone,

The hoary hills shall disappear.

The changing main shall ebb and flow,

The waning moon be lost in night,

Thou only shalt victorious go,

Forever joying in thy light.

The Love Songs, numerous, full of headlong passion, and

set to very attractive melodies, form the largest class, and their

fervour and naivete give them a certain piquancy which is not

unpleasing. But the graces and felicities of the Home are not forgotten;

there are many poetic addresses to newly-made brides and frolicking boys

and girls, and lullabies to the babies. One of the most popular songs in

the Highlands is a lilt to a little Highland lassie—

O, my darling Alary, O, my dainty pearl!

O, my rarest Mary, O, my fairest girl!

Lovely little Mary, treasure of my soul,

Sweetest, neatest Mary, born in far Glen Smole.

The Patriotic Songs are a large class, for the

Highlanders love their barren land- — her very dust to them is dear.”

Her historic scenes and the Highland dress, language, and music are

never-failing themes, in discoursing on which the bards occasionally

added such half-serious and wholly forgiveable touches of exaggeration

as the following—

Now, let me tell you of the speech and music of the Gael,

For Gaelic is a charming tongue to tell a bardic tale,

Fain would I sing its praises—pure and rushing, ready, ripe,

For Gaelic’s the best language, the best music is the pipe!

But of all the Northern songs the elegies and other Lavs

of Sorrow are the most striking and characteristic. The Highland Lament

is a thing by itself, having no exact counterpart in any other language,

its wild, rich music presenting a perfect picture of the weird and grand

scenery in which it had its origin. The Gaelic race has been cradled

into poetry by suffering, and its spirit has been bathed in the gloom of

lonely glens and northern skies. Hence its songs have always given

superb expression to what Ossian calls “the joy of grief.” There is,

however, this difference, that while in the older songs the sadness is

unrelieved and oppressive, the more modern introduce a chord of

sweetness to form a very luxury of sorrow. Thus a bard laments the death

of a child—

She died—as dies in eastern skies

The rosy clouds the dawn adorning;

The envious sun makes haste to rise

And drown them in the blaze of morning.

She died—as dies upon the gale

A harp’s pure tones in sweetness blending.

She died—as dies a lovely tale

But new begun, yet sudden ending.

In bright contrast to these lays of grief are

the Humorous Songs—serio-comic ballads, parodies, and biting satires,

the latter being far too numerous.

With the exception of the wickedness in these satiric

outbursts and a passing wave of depravity that swept over Highland poesy

in the end of last century, the songs are pure and noble.

Their Ethics are remarkably high, and their continued popularity and

influence among the Gaelic population must be regarded with

satisfaction.

The Language in which these lyrics have been composed is

one that is unusually well fitted to be the vehicle of sentiment,

readily lending itself to those little garnishments in which Celtic

poets delight. It is rich, mellifluous, and copious in poetic terms,

especially adjectives, which the bards used with lavish but discriminate

profusion. Of its expressiveness and natural poetry, these bards had the

highest opinion—

This is the language Nature nursed

And reared her as a daughter;

The language spoken at the first

By air and earth and water,

In which we hear the roaring sea,

The wind, when it rejoices,

The rushes’ chant, the river’s glee,

The valley’s evening voices.

From a literary point of view one great charm of Gaelic

verse lies in the extraordinary diversity and complexity of

its Metres. Abundant use is made of the ordinary measures familiar in

English poetry —the iambus and the trochee—but recourse is also had to

the difficult anapaest and the high-strung dactyl, and all four are

woven into numberless combinations, such as would delight the soul of an

English poet, but of which English itself is unfortunately incapable on

account of its limited selection of dissyllabic and trisyllabic rhymes.

A common device of the Gaelic bards was to make the latter half of each

stanza the first of the next stanza, as in No. 12, Part I., of this

collection. Gf course, that arrangement required the same rhyme to be

maintained throughout the whole song, but such is the wealth of Gaelic

assonance that this was accomplished with ease. Indeed, it is no unusual

thing for eleven out of twelve lines to rhyme, and sometimes one rhyme

is carried through twenty verses. The most common form of verse in all

Gaelic poetry—Scottish and Irish, ancient and modern—is one in which the

close of one line rhymes with an accented syllable in the middle of the

following line. This leonine rhyme may be exemplified by the opening

verse of the ancient poem known as “The Aged Bard’s Wish ”—

Oh, lay me by the burnie’s side,

Where gently the limpid streams,

Let branches bend above my head,

And round me shed, O Sun! thy beams.

But in many songs every line bristles with rhymed words,

often words of more than one syllable, as in the song No. 16 or hymn No.

4. This free use of intricate rhymes, combined with the headlong sweep

of rhythm found in the best songs, can only be imperfectly reproduced in

English, but an imitation of one of Macdonald’s stanzas may illustrate

some points of the literary structure of Gaelic verse—

Clan Ranald, ever glorious, victorious nobility,

A people proud and fearless, of peerless ability,

Fresh honours ever gaining, disdaining servility,

Attacks can never move them but prove their stability.

High of spirit, they inherit merit, capability,

Skill, discreetness, strength and featness, fleetness and agility ;

Shields to batter, swords to shatter, scatter with facility

Whoever braves their ire and their fiery hostility.

Neither is the aid of apt alliteration neglected in the

adornment of these songs, which indeed possess, in an unusual degree,

all the attractions of form and colour found in the best lyrical poetry.

The Music of Gaelic Songs bears a family resemblance to

that of the Scottish Lowlands, but with all its peculiarities

accentuated. In point of fact, the music of South and North was

originally the same, for the Scottish Lowlanders in discarding the

ancient language of the Scots had the good sense to retain their

melodies. Further, it is well known that from the days of Burns, and

probably from a much earlier date, the national music of Scotland has

been increasingly enriched by the adaptation of Gaelic tunes to Scotch

or English words. These tunes follow closely the rhythm of the Gaelic

words, and therein lie much of their undoubted power and originality.

But this very connection has a peculiar effect on the English songs, to

which many of the airs are wedded. All Gaelic words are accented on the

first syllable, and in consequence lines end with an unaccented, or

sometimes two unaccented syllables. Of course, the melodies follow this

pecularity—the tunes, or parts of a tune, seldom ending on the note

after the bar. In the English and Scotch dialects, however, the range of

dissyllabic and trisyllabic rhymes is extremely narrow, and Scottish

poets have been compelled to eke it out by using diminutives and

plurals, and adding numerous “O's” at the ends of lines, in their

efforts to bend the intractable Saxon tongue to the cadences of Gaelic

music. Similarly the characteristic of Scottish airs, known as “the

Scotch snap,” is to be attributed to the greater difference made in

Gaelic between vowels that are long and accented and those that are

short and unaccented. The absence of the seventh note, B (te), in the

ancient Scottish scale no doubt added to the quaintness of the national

airs, but a much more striking feature was, and is, its modal character.

The old harpers are said to have been extremely fond of the major

mode, an lit, but that mode does not obtain in Gaelic tunes, as now

sung, the predominance which it has in other modern music. One of the

stumbling-blocks which the ordinary musician finds in Scottish music is

that, not content with the ordinary major or even the more uncommon

minor, it must wander away into the rough and unfamiliar Dorian mode.

But in Gaelic music this peculiarity is emphasised, the tunes in the

mode of the second (ray) being, if anything, more numerous than those in

any other mode, while it is not unusual to meet with melodies in the

modes of the third, fourth, and fifth notes of the scale. Probably,

however, the intrinsic beauties of Gaelic airs will be found sufficient

recompense for these and other singularities which, in the eyes of many

admirers, are but additional beauties.

The Hymns of the Scottish Highlands have hitherto

attracted little notice; nevertheless they are fairly numerous and many

of them possess great merit. They are never used in public worship now,

but they were certainly used in early times, and a few hymns o! the

ancient Columban Church have been preserved in monastic

libraries—antique compositions in Latin or Gaelic, or both. In the

middle ages the sacred poetry would seem to have been of a lower lype—imaginary

conversations like the so-called “Prayer of Ossian," preserved in the

Dean of Lismore’s Book (1512), and verses to he used as charms. The

modern sacred poetry of the North began with Dugald Buchanan by the

shores of Loch Kannoch about the middle of last century, but the most

voluminous and popular writer of Gaelic hymns has been the Rev. Peter

Grant of Strathspey, whose collection, first issued in 1809, is highly

esteemed throughout the Highlands and the Gaelic districts of Canada,

under the name of the lays of l'adruig Grannd. Besides these poets there

have been many hymn-writers in the North. MacGregor, MacLean, Morrison,

and others, some of whom have contributed but one successful hymn to the

sacred anthology of their country. In that anthology it will be found

that, along with undoubted orthodoxy, there is a certain echo of the

secular songs, which is particularly noticeable in the use of poetic

phrases such as Din nan tin “God of the elements,” Dia nam feart, “God

of (many) attributes,” Slanuigkear nam bitadh, “Saviour of (many)

victories.” The hymnology of the Highlands shows little trace of the

religious currents of the present century, and its chief characteristic

is a sad earnestness, rising at times into a passionate pessimism. A

stern theology harmonises well with the environment and history of the

Highlander, and whether as Pagan or as Calvinist he is most like himself

when chanting eternal “Misereres” of unutterable pathos. The three great

themes of Highland hymns are Sin, Death, and Judgment a trinity which is

very real to the sacred bard, and whose shadow lies across all his

thoughts. Hence the solemnity and awe of many of the hymns. What English

poet would think of presenting for our meditation a picture such as

this—

For mortal man life is quickly past,

The King of Terrors shall hold him fast,

When sick and dying, behold him crying—

“Ah! tell me, friends, is this death at last?”

“What throes of anguish are these,” he saith,

“That rend my bosom and stop my breath?

New terror thrills me, strange horror chills me —

Oh, tell me truly, can this be death?”

Yet the pages of Buchanan and Grant contain verses even

more terrible than these. At the same time it would be a grave

misrepresentation to say that all Highland hymns are of this gloomy

cast; even in the present collection will be found many Christian songs

of the brightest and happiest description, though, happily, the language

contains no hymns that show the levity frequently found in popular

English hymn-books.

The Sacred Music of the Highlands has a close affinity to

the secular melodies, and in some cases Gaelic and other suitable tunes

seem to have been adapted to sacred words. But numbers of the hymns have

their own proper tunes, many of them sweet, expressive, and in every way

worthy to be the exponents of religious feeling.

Besides the hymn tunes, there is another class of sacred

melodies in the Highlands which is very interesting—the Psalm tunes,

which differ widely from those familiar to the English-speaking world.

This is specially true of the small number of very long and elaborate

tunes that have been used in the North for many generations, and which

are known as the “old” tunes. Their origin is unknown, for though there

is a tradition that they were brought into Scotland by devout Highland

soldiers returning from the Protestant wars of Gustavus Adolphus, they

bear little resemblance to the Psalm tunes of Sweden and Germany. If,

indeed, any such imported foreign music formed the basis of Gaelic

psalmody, the superstructure has probably been moulded by the chants

used in Highland worship before the importation took place. In the Psalm

tunes as we now have them, the predominance of local colouring is very

marked, and it may be said that, even more than the unquestionably

native music of the hymns, these Psalm tunes express the deep

seriousness of Highland religion.

The present collection contains the six “old” tunes, as

well as the Highland forms of the modern Psalm tunes, and in preparing

it the editor has had the intelligent and valuable assistance of

Gaelic-speaking ministers and precentors.

You can download

this book here |