|

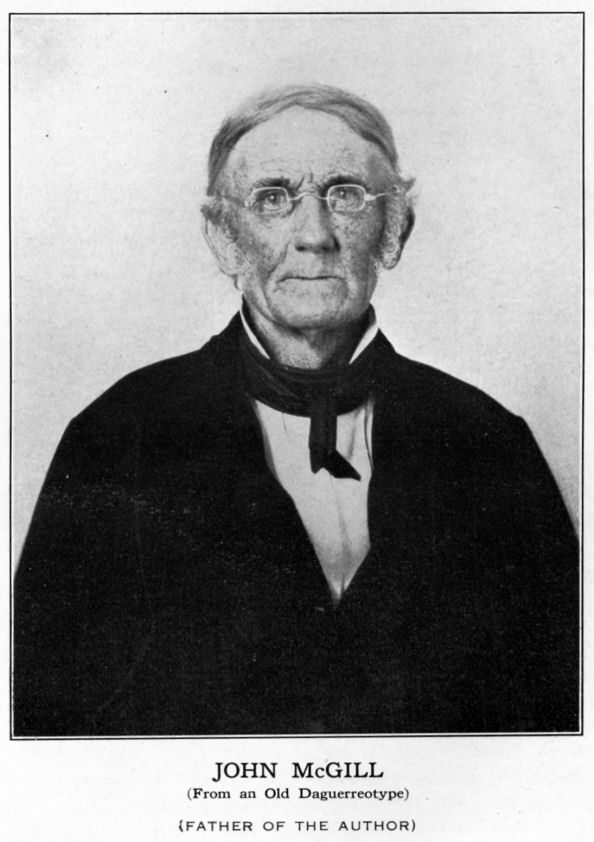

McGill, John—Son of Patrick.

John McGill, the eldest son

of the family of the Pioneer, was born at Duncan’s Island on the

Susquehanna, in Northumberland county, Pa., Oct. 19, 1795, and in December

of the same year was domiciled on the banks of French Creek on the McGill

Patent "Good Intent," whereon his father established his abode and permanent

dwelling place.

John grew to manhood in

surroundings and under conditions already described; and June 12, 1822,

married Isabella Ryan, daughter of John and Catherine Ryan of Woodcock

township, Crawford county, Pennsylvania.

Isabella, aforesaid, was born

Oct. 28, 1800.

They established their home

on the North Hundred of the Good Intent Patent, where they passed the

remainder of their days, and raised a family of two sons and six daughters;

two daughters died in infancy.

Isabella McGill; died March

26th, 1876; aged 76 years.

John McGill; died Oct. 27th,

1878; aged 83 years.

Their life during the

fifty-four years they lived together was entirely and happily harmonious,

though each bore a strong personality independent of the other. There was no

incompatibility; their purposes ran parallel and they moved steadily to

accomplish the ends in view harmoniously and without friction of any kind.

The result was a well regulated household.

John McGill was five feet

eleven inches high - of compact, well knit frame - symmetrical mold - quick,

easy motion, and active as a deer. In the athletic sports of his youthful

days he had few, if any, competitors who could excel him. He could jump

higher and leap farther than most of them and was a sprinter of wonderful

agility, as well as a wrestler whose back seldom touched the ground. These

sports were common with the young people of his day and came in as an

interlude between rolling logs and clearing the land.

They - John and Isabella -

had moved into their new house on the North Hundred. "The clearing" was in

front, many broad acres covered with the debris of the forest extending

almost to their door. The outlook was wild and jagged, but the workers were

looking beyond to the waving fields of golden grain that in after years

spread a gorgeous mantle over the scene.

The rain was coming down in a

steady pour, and John was standing in the door leaning against the jamb

looking out toward the dripping forest.

Isabella came into the room

from the pantry and in her businesslike way remarked, "John, we are nearly

out of meat!"

John answered not a word, but

glanced up toward his rifle that hung on the wall, then went out to the

south end of the porch - scanned the outlook to the southwest - returned -

took down the rifle and thoroughly cleaned and carefully loaded it. He then

resumed his place, leaning against the door jamb with his rifle by his side,

looking out at the falling rain.

The deluge ceased and only

drops were pattering down from the tops of standing trees. Away to the

northeast a magnificent buck bounded into the opening and took its way

across the clearing. It was a long shot from the porch to the course of the

fleeing deer, but without changing position the rifle came to his shoulder -

his keen, brown gray eye, like a flash of light, glanced along the sights -

"Crack!" and Isabella had her answer; the problem of the empty meat barrel

was solved, for the time being, at least.

Years passed. The clearing in

front of the house had lost all of its repulsive features, and in place of

brush and logs and stumps was now embossed with the emerald green of the

growing crops. The forest was creeping backward on the slope of the next

plateau. The sound of the woodman's ax was ringing along the verge of the

dying woods.

Near the summit of the next

rise, on John's hundred, was a wonderful spring - wonderful in this respect;

that the other springs bubbled out at the foot of the hill, while this one

boiled directly up on top of the hill! It had there formed for itself a

little basin which retained the water to a certain point from whence the

overflow rippled off down to join the waters of the lower draft. Looking

into this basin of pure, cold water one could see the tiny jets boiling

right up out of the earth, causing bubbles on the surface, and here and

there building up little mounds of fine sand around the jet, as if forming

the crater of a mimic volcano. The water was pure, soft, cold and healthful.

Nature had shaded the spot with a growth of young maples, while farther away

stood the larger growth of oak and chestnut. Such a phenomenon as this

spring presented had not gone unobserved and the wood men had carried bark

and spawls and made a little platform on which they could lie down and drink

out of the cauldron.

It was about 10 o'clock in

the morning and John, who was splitting rails a few rods farther down the

hill, became thirsty and went up to the spring to get a drink. It was a

delightfully cool place in that alcove formed by the young maples, and he

stood there for a minute fanning himself with his straw hat, and then lay

down on the platform and took a long, cooling draught from the spring. As he

raised up on his feet he found himself confronted by a large, black bear,

and so close, that had each extended a forearm they could have shaken hands.

The situation at once became interesting and the possibilities of high

tragedy were imminent. The man and the beast looked one another square in

the eye; the hair went up erect on the back of Bruin and he exhibited a

mighty fine set of teeth. With the exception of a snarl from the bear at the

instant of surprise no words were spoken or sound uttered.

There were men in the woods

at work, thirty or forty rods away, but to call for assistance would

precipitate an onset. The young maples might afford means of escape, as John

could spring into the top of one nearest him with the agility of a cat and

could then call for help. He thought of this mode of escape and determined

to adopt it if he had to, but never for an instant did he glance toward the

maples or remove his fixed stare from the eye of the beast; like statues

they stood and stared - it was a quiet battle of the nerve force of the man

and of the beast.

Bruin had approached that

spring with no hostile intentions; he simply wanted a drink of water; he was

not on a man hunting expedition by any means and his surprise at the

encounter was very great, but it was not in bear nature to decline a

conflict when the enemy was so near at hand, and the attack would have been

inevitable had the surprise been less complete, and that, with the gleam of

the woodman's eye, caused him to hesitate, and he was lost. There was a

fascination there that paralyzed his aggressive nature and held him sternly

at bay. John saw that the bear quailed under his fixed stare and threw into

it all the intensity he could command.

He had never heard of such a

thing as hypnotism, and would not know the meaning of the word if he saw it,

and would have been greatly amused at the theory had it been explained to

him; yet, nevertheless, John hypnotized the bear.

And now began the tactics of

retreat. Stealthily Bruin, without taking his eye from that of his

antagonist, raised one foot and with scarcely perceptible motion, placed it

a few inches to the rear - he was stealing away - then followed in the same

manner another foot and minutes elapsed before the brute had moved half a

yard away, at the same time maintaining a vigilant, hostile front. John was

well aware of the danger of any precipitate action on his part at that

crisis and stood as immovable as the Sphinx. He realized that a separation

was about taking place and that such action was very desirable and he would

throw no obstacles in the way, but at the same time he made up his mind to

have some fun out of the predicament as a compensation for the strenuous

time that had been imposed upon him.

Bruin was now going backward

with accelerated speed and had half turned to flee when John sprang out

toward him, giving out a yell that would discount all "Noth Calina" rebel

yells that were ever heard. There was a whirlwind of dried forest leaves

went over the knoll back of the spring. The bear was ahead of the cloud, and

John was in it, sending forth such howls as were never before heard along

those hills. The terrorized brute now took to a tree for safety, and around

its base the woodman pranced in fantastic style, still keeping up the clamor

of those awful yells, until the outcry brought, as he intended it should,

men with dogs and guns to investigate the cause of the tumult. Bruin then

and there paid the penalty for having looked in the eye of a man, and there

was a replenishment of other empty meat barrels, but not of ours, for John

and Isabella did not care for bear's meat.

Numerous incidents are

related of the frequent and successful intervention of John McGill in

quieting riotous proceedings, and preventing personal encounters in the

whisky drinking times of his early manhood. He never drank intoxicating

beverages; he would not tolerate them on his premises, and on this account

apparently incurred the ill-will of many of his neighbors.

The lurid light from the

fires of five distilleries could be seen from his door of an autumn evening,

and the morals of the community were being debauched by drink. So uniform

was the custom that ministers of the Gospel imbibed the red ruin and fine

minds were being wrecked by the pernicious habit.

John, standing almost alone,

declared a war upon it. He gave out the mandate "Touch not; taste not;

handle not the unclean thing. I will not furnish it to my men, nor shall it

be used on my place if I can prevent it." Men cursed him, but it mattered

not, no change of program was possible.

The necessities and isolation

of the new community made co-operation indispensable, and raisings, log

rollings and sundry gatherings, where the strength of the community combined

to do the heavy work were common, and at all these whisky flowed like water

and men got drunk and fought and behaved badly.

With his entire force, John

was always on hand rendering efficient service on these occasions, but

standing aloof when the drunken orgies began. Maddened with drink, good men

would quarrel and strip for the fight; great, strong, savage men whom no one

could pacify. John would quietly step between them, and with a few words

subdue their angry passions, the belligerents often shaking hands and

parting in the best of humor. This was so common that his reputation as a

peacemaker became widely known, and as long as that generation lived it was

a part of the unwritten history of the times.

He as well as others had to

call on his neighbors for help, even as they called on him. He was about to

erect a large frame barn. The timbers were on the ground, ready to raise,

and all the men along the wayside were invited, and came. It was the custom

to pass the jug before putting up the first bent. Everything was ready, but

the jug did not appear.

Then came a committee who

informed him that the customs of the country must not be broken, and his

barn could not be raised without whisky. He replied, that such being the

case, the timbers must rot on the ground. "But, gentlemen," he said, "I have

as fine a supper prepared for you over there in the shade of the trees as

you ever sat down to; never mind the barn, but please come over and take

supper with me before you go." They raised the barn.

His harvest was on hand, and

it was rich and bounteous and great, and only he and a hired boy on the

premises; but he had harvesters engaged, some of whom had received part pay

in advance. He set the day on which to begin the work and rode out to notify

his men when to come. Some of them lived two or three miles away.

The first man he came to

carelessly remarked, "Of course, you will have whisky; everybody furnishes

whisky in harvest?"

"No, sir. I will not," was

the reply. "I will furnish my men everything that is good, but whisky is not

good for men and I will have none of it; and you know, Jake, the good book

says: `Cursed be he who putteth the bottle to his neighbors' lips,' and I

don't want to be reckoned with that class."

"No whisky, no work," was the

answer. He rode on, and with each one of his men substantially the same

conversation took place. The situation was becoming interesting, whereat he

was greatly amused. He saw that a combination had been effected to compel

him to recede from the position he had taken on the temperance question, and

he knew that these poor laboring men, so largely dependent on him in many

ways, had not originated the objection; that it was the work of a hidden

hand that dared not meet him openly, and he laughed audibly and rode

blithely homeward. When he arrived he looked out over his broad fields of

ripening grain with no harvesters in sight, and he laughed again and was

happy.

He told Isabella all the

happenings of the day. "The miserable curs," she indignantly exclaimed.

"Time and again you have given them food when they were hungry and filled

their meal sacks when they were empty, and for these acts have exacted

nothing on the day of settlement. Where now, do they expect to get flitches

of bacon, hunks of pickled pork and sacks of flour and meal when they have

no money and there is no work to be had? They will find that such goods will

not be handed out free at Mr. Saeger's new distillery.

"It is too bad. I will tell

you, John, what we will do. Anna and Sarah must take care of Gus, and I will

go out into the fields with you, and you and I will take care of that crop."

And then he smiled and gently

said: "No, no, Isabella. Your plans are excellent, but wait. Those men have

three days in which to think, and I left them thinking. They are not fools,

and on Monday morning they will be on hand" - and they were. The harvest was

gathered in, and never again was the question of whisky raised at gatherings

on the North Hundred of the "Good Intent Patent."

Never, within my

recollection, was there a time when homeless waifs, ranging from infancy to

tottering age, were not sheltered beneath his roof, receiving all the

kindness and care bestowed on members of his own family.

The humorous side of his

nature was always in evidence, and he would crack a timely joke with a

bishop as readily as with a farm hand, and he would extort genuine fun out

of conditions and circumstances that would have been exasperating to other

men.

Once in the night he came

upon a man with a partly filled bag, stealing grain from his bin. John

collared him, and compelled him to fill the sack full and shoulder it and

carry it home, fiercely admonishing him as a scoundrel, that if he ever

mentioned the theft to a living soul he would have him sent to jail.

He got great fun out of

compelling a thief whom he caught stealing roasting ears, to fill a bag

full, and come out into the highway and carry it home. He never prosecuted

any one, but he enforced his own penalties on pilferers by threats of the

law in case of non-compliance, and

the punishments he inflicted were of such unique character that no offender

ever repeated the offense.

He was for over fifty years an

official member of the M. E. church, and through all this strenuous life

Isabella stood by his side, fully his equal in intelligence; in moral and

intellectual force and his superior in learning; the mother of his children,

and their instructor and guide; the queen of the household unsurpassed in

the great qualities of a godly motherhood that transmits blessings that

never fade.

Many years before his death, all

animosities on the part of those who opposed him when he first marked out

his course in life, had disappeared. He never swerved a hair’s breadth from

what he considered the line of duty. His honest, unassuming,

straightforward, consistent bearing, at all times and under all

circumstances won the hearts of men, and when the time of his departure came

he was the most respected and best loved of all that strain of noble old men

who came in with the settlement and cleared away the forest wilds. |