MANY

PEOPLE BELIEVE leprechauns are simply a dwindled folk memory of the tall

and graceful Tuatha de Dcinann, an elvish folk said to have ruled

Ireland by magic in ancient times, before the arrival of the Sons of Mil.

This is not so. Leprechauns are a separate race, almost as ancient and as

proud in their own way as the Tuatha, and they take great offence

at being mistaken for anything other than what they are.

MANY

PEOPLE BELIEVE leprechauns are simply a dwindled folk memory of the tall

and graceful Tuatha de Dcinann, an elvish folk said to have ruled

Ireland by magic in ancient times, before the arrival of the Sons of Mil.

This is not so. Leprechauns are a separate race, almost as ancient and as

proud in their own way as the Tuatha, and they take great offence

at being mistaken for anything other than what they are.

Others say leprechauns are just a

load of old cobblers. Which is true of course because a thousand years is

a sprightly age for a leprechaun, and they are famous for their

shoemaking; but they have many other talents besides. They are also great

tinkers (partly because in the old days their shoes were made of metal)

and have proved themselves perfectly equal to much modern technology. Many

a tractor in the west of Ireland owes its survival more to the tinkering

of leprechauns than the care of the local garage, which it will not have

seen for years.

Leprechauns are generally classed

among the solitary faeries of Ireland as opposed to the far more common

trooping faeries. Most tales speak of encounters with single leprechauns

so it is clear they enjoy their own company, but they also have their

sociable moments

which are what we are more interested in. Leprechauns are less

domesticated when it comes to adopting human households than, say, the

brownies of Scotland or the kobolds of Germany, or their relations in many

other countries, but they have been known to attach themselves to human

families and even follow them when they move, which is how there come to

be leprechauns in places like North America and Australia.

Most leprechauns live in Ireland

thought where they have evolved a quite distinct identity from the Little

People of neighbouring countries. In general they are more independent of

humans, more interested in gold and more witty than other Little People.

Until a century or two ago no-one in Ireland doubted them any more than

they doubted the existence of the Pope in Rome. In the first years of the

twentieth century a famous scholar named Evans Wentz was impressed by the

stir in Mullingar over a leprechaun who had apparently been parading

himself before half the children of the parish, and many of the grown

people too. Everyone was out looking to catch it. Then the rumour spread

that it had been caught by the local police. But when the scholar,

continuing on his travels, told this rumour to an old man at Ballywillan

where he stopped for the night, the old man laughed and said: ‘Now that

couldn’t be at all, for everybody knows the leprechaun is a spirit and

can’t be caught by any blessed policeman, though it is likely one might

get his gold if they got him cornered so that he had no chance to run

away.’

In those days even judges could

still confess openly to having met leprechauns without much fear of being

laughed off the Bench. There is more scepticism now. In fact, to be

perfectly truthful, most people in Ireland today do not seriously believe

in leprechauns at all, however partial they may be to the idea of them.

And there are those who find the whole subject embarrassing because it

reminds them of aspects of the past they would rather forget. Which is

fair enough really. Each to his own. Leprechauns themselves are quite

happy with this state of affairs. It means there is that much less chance

of being rudely interrupted while working away under the hedgerow by some

great human eager to squeeze your treasure out of you. And it is easier to

play tricks when your victim is unaware of your existence.

Because they are a kind of faery,

leprechauns are often invisible. They may pass by as a swirl of dust, so

in the old days men would raise their hats and women curtsey if a pillar

of dust blew by, just in case. If you throw your left shoe at the cloud

and it is really a leprechaun, he has to drop whatever he is holding,

including any bags of gold; but if he is not holding anything, you may

just gain his ill-will from it.

In the old days people would also

leave out a dish of milk or fresh water at night for leprechauns, avoid

cutting down hawthorn or whitethorn bushes, leave the dregs in their

glasses when going to bed, and many other little courtesies to keep in

with them. That so few people now take the trouble is the cause of endless

bad luck which might otherwise be happily avoided.

Leprechauns have been known to

‘adopt’ families and move in with them, though this is rarer than with the

Little People of other countries. Often the first sign that a leprechaun

has moved in is that things start to go missing, or turn up in unexpected

places. Sometimes even a table or a chair might be thrown across the room,

and the whiskey or milk will be found to have gone down overnight, or to

have been topped up with water. If all this happens, the family will know

they must start leaving out little presents of food and drink and anything

else that might take the little fellow’s fancy. Then, with luck, instead

of doing mischief the leprechaun will go round the house and barns at

night finishing off jobs that the big people have had no time to do.

All this can happen without the

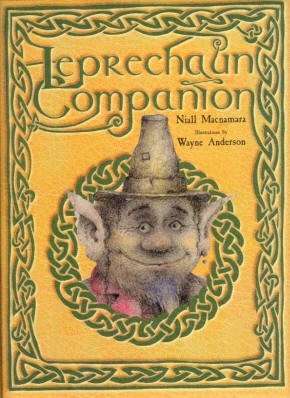

family clapping eyes on their guest. But those who have seen or met a

leprechaun most often describe him (it nearly always is a ‘him’) as being

two to three feet tall, with a wizened face, bright eyes and a red nose.

His dress varies but tends to be old-fashioned, in mainly greens and

browns with touches of bright red, and often shabby. Some people have met

leprechauns only a few inches tall while others seemed barely shorter than

humans, but usually their size falls somewhere in between. This is because

their form is more flexible than ours. They can even adopt the shape of

animals, it is said, which you can tell by the strange behaviour of the

creature, especially if it talks to you.

One sure way of seeing leprechauns

is to carry a sprig of four-leaf clover or shamrock somewhere about your

person, or a stone with a natural hole bored through it, or a piece of

wood with a knot that has been knocked out. Some say a sprig of the faery

cap flower (also known as lusmore or foxglove) conveys the same power, but

this is disputed. Often also the robin redbreast will lead you to a

leprechaun because they are great friends. In fact a robin is the most

common bird form the leprechaun will adopt, for which reason it is

especially bad luck to kill or trap a robin, even accidentally.

HERE IS A SENTIMENTAL notion abroad

of leprechauns being bright, sunny little folk only too eager to surrender

their pots of gold to passing strangers, but this is far from the truth.

It has been known to happen, but it is rare. Leprechauns are great misers,

and like all misers they do not just collect gold for the sake of giving

it away to passing strangers, not without good cause anyway. As to being

cheerful, well some leprechauns are and some aren’t, purely as a matter of

temperament. But however sunny their disposition, it may well not be

apparent to one of us. Since most humans have only ever really been

interested in leprechauns for the sake of their gold, we should not be too

surprised if they are wary of us and perhaps harbouring a few grievances.

So the thing to remember about

leprechauns should you happen to meet one is that they can be as nice as

pie, but they may also seem cantankerous, vindictive, spiteful old

curmudgeons, or anything in between. A bit like humans really. But on the

whole they tend more towards mischief. They love pranks, especially if

there is a lesson in it for the victim. So when meeting a leprechaun it is

best to be courteous and friendly. And think twice before accepting any

gift that is freely offered.