And if St. Oran’s Chapel be indeed the building erected

by Queen Margaret, it is not without interest to think that in that low,

round archway, which still remains, we may see the door from which the

fierce King Magnus is said to have recoiled with awe when he had attempted

to enter the sacred building.

But already we have been carried

down the course of centuries far—too far—from the time in which all the

real interest of lona lies. Or if it be indeed part of that interest to

look on the ruins of St Oran’s Chapel, and to think that it may possibly

be the very building erected by the wife of Malcolm Canmore, at least let

us not forget that the long, long period of 500 years lay between that

date, which now seems so old to us, and the date of Columba’s ministry.

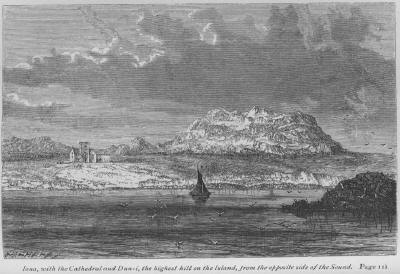

The grey tower of the cathedral, standing "four square to all the winds

that blow," ancient and venerable as it looks, is of still more modern

date. The oldest portion of it may belong to the close of the twelfth

century—that is to say, more than 600 years nearer to us than Columba’s

day. All these buildings before us are the monuments, not of the fire, the

freshness, and the comparative simplicity of the old Celtic Church, but of

the dull and often the corrupt monotony of mediaeval Romanism. After all,

the real period of lona’s glory was not a long one. It is almost confined

to the life of one man, and to the few generations which preserved the

impress of his powerful character.

Let, us then for a moment go back to

his time, let us look on the Island, as it was before one stone of the

churches now ruined had as yet been laid upon another, and let us fill in

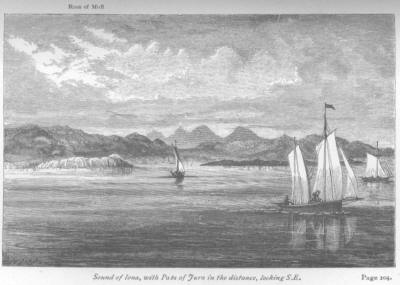

the background of the picture before us as it is and as it was. Across the

narrow strait lie the low, rounded, but rocky hills of red granite which

here constitute the Ross of Mull. These, broken up into innumerable rocks

and islets, stretch from one, entrance of the Sound in the N.E., to the

other entrance in the S.W. Looking down the .vista of the Sound in this

last direction is the comparatively open sea,—with the blue mountains of

Jura appearing in the far distance to the left over a depression in the

hills of the Ross. Towards the other, or north-eastern entrance of the

Sound, the horizon is entirely bounded by the coast of Mull, and of the

smaller Islands of Ulva and Inch-Kenneth. But these coasts are receding

and fore-shortened shores, reaching far up Loch-na-Kael, an arm of the sea

which nearly divides the Island of Mull into two parts. Another similar

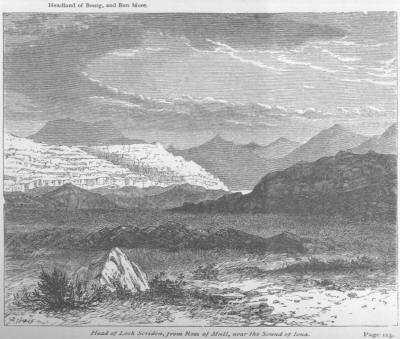

arm of the sea called Loch Scriden branches off to the eastward; and

although its line of coast is concealed from the Monastery of lona by the

low granites of the Ross, yet the mountains along its sides and at its

farther end give additional variety to the sky lines as seen from

Columba’s cell. These two arms of the sea clasp round the base of Ben

More, whose summit appears rising above a great precipitous headland

called Bourg. The upper portion of this headland is a great mass of nearly

horizontal terraces of trap rock, diminishing pyramidally to the top;

half-way down; these terraces break into lofty precipices which run round

the headland on every side, and are seen extending along the shores of

Loch-na-Kael with little interruption for many miles, but with much

variety of height. At the foot of this range of precipices there is a

steep green slope (at the angle of rest) into the sea. After rains, a

rivulet breaks over the brow of this precipice at the point where it

fronts lona; and when strong winds are blowing from the westward, the

water of this stream is blown off in a cloud of vapour. Grand shadows are

thrown, in fine weather, along the range of cliffs, varying with the

advancing hour, and with every passing cloud. This great headland, with

all its varied and noble outlines, is the most conspicuous object in the

view from all the old ecclesiastical sites upon Iona; and during the many

years of Columba’s ministry, they must have been the most familiar of all

outlines to his eye. Far off, along the perspective of the receding shore,

and close under the point round which the range of cliff passes out of

sight, lies the little Island of Inch-Kenneth—where, in 1775, Dr. Johnson

was so hospitably entertained. To the left lie the opposite shores of

Loch-na-Kael - all hills of trap, disposed in line; heathy, and receding

towards the head of that arm of the sea. Above them, low down upon the

sky, rises a portion of the far-off Hills of Morven, lying on the other

side of the Sound of Mull.

The slope of arable land upon lona

itself, which lies between its rocky pasture-hills and the shore, rises

towards the N.E., and from the Torr-Abb shuts out farther view in that

direction. Let us therefore now come down from this point of observation,

and follow the path towards the northeastern end of Iona, along which

Columba must have often walked. It brings us presently alongside of an

elevated ridge of ground, which seems like an artificial terrace, and on

ascending it this suspicion of its origin will be confirmed. Beyond it,

lies a hollow and morass — the only one on the Island—which marks the site

of an old reservoir of water for the turning of a mill wheel. Passing

along this old mound of dry and pleasant turf, the view to the northward

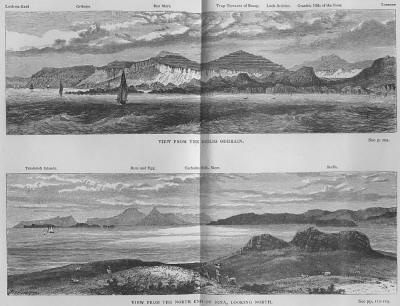

opens considerably. The northern half of the Island of Mull still bounds

the horizon with its long low hills of terraced trap covered with dark

heathy pasture. But nearer, some six miles off, there is an Island of

curious form, flat topped, with precipitous sides, sloping upwards towards

the west, and then ending in a cliff singularly sharp in outline. If the

sun be low and shining strongly, casting its glorious light on the

precipices of Bourg, and the rocky shores of Gribune, it will be seen that

this curious Island is marked with a strange band of columnar shadows,

with two dark spots on the face towards lona. This is Staffa, and one of

these dark spots is its now celebrated cave. How strange that this great

work of nature should have lain for so many ages so close to one of the

most frequented and most celebrated Islands on the shores of Britain, and

that not a whisper of its wonder and its sublimity should have been heard

among men!

Pursuing our walk towards the

northern end of the Island, we regain the road leading to the pastures

which seem to have been specially devoted to the dairy cows, and along

which Columba’s brethren brought home to the Monastery their daily pails

of milk. As we ascend the slopes which fall away from the foot of Dun-i—the

highest hill on the island —we come upon a region of "Link land"—that is

to say, of shelly sand, covered with close, soft, and springy grass. This

extends in flats, and in swelling undulations, to the rocky shore, or to

the point where stormy winds have broken in upon the sward, and scattered

the fine sand in wreaths almost as white as snow. From this pastureland a

wide view opens before us to the northward. The hills of Mull are seen

terminating in a long promontory and a rocky headland. The intervening

wide expanse of sea is dotted with Islands all of the same curious form

and shape—precipitous in the side and perfectly flat in outline, except

one Island, out of the middle of which rises a low conical hill, with a

perfectly symmetrical outline on either side. This is now known under the

name of the "Dutchman’s Cap," and is, and must always have been, an

invaluable landmark for boats navigating in stormy weather through such a

dangerous archipelago of rocks. Far beyond these islands, and far also

beyond the headlands of Mull, rises in a clear day a long ridge of sharp

and peaky mountains, sinking in noble outlines into the ocean on the west.

These are the Islands of Egg and Rum. And beyond these, again, to the

right, low down upon the horizon, may be seen, traced against the distant

sky in the faintest but purest blue, a sharp serrated range of mountains.

These are the Cuchulin Hills, in Skye. To the extreme left—that is, to the

west—the horizon is occupied, across some twenty miles of sea, with a low

hummocky outline, ending in detached spots of hill, which only appear at

intervals above the waves. These indicate the Islands of Tyree and Coll.

To the south-west is the open Ocean, with all its vastness, its freshness,

and its power.

From this part of the Island also

the view to the eastward is finer than from the old monastic sites,

because lona here overlaps the end of the Ross of Mull, and the eye ranges

along its northern coast, thus commanding the mouth of Loch Scriden, as

well as the receding shores of Loch-na Kael. On a calm fine evening in

autumn, when the atmosphere has that singular clearness which is then

often to be seen in the Hebrides, I know no view in any part of Scotland

more beautiful or varied than the view from the north end of lona. The

distance on the map from the Cuchulin Hills, in Skye, to the Paps of Jura,

is 96 miles. Both are clearly visible, the one to the extreme north, the

other to the extreme south. This is indeed a wide horizon, with such a

wealth of Cloud and Sea and Mountain as belongs to very few spots in any

country.

Returning to the Torr-Abb and the

Reilig Odhrain, there is another walk which is of much interest as

connected with the detailed account left us by Adamnan of one of the last

days of Columba’s life.

This account is so characteristic in

its combination of incidents, some of which are perfectly natural and

others of which are highly imaginative, that it may be well to give a

short abstract of it here.

One day in the thirtieth year after

Columba’s landing on lona, a sudden flush of colour and a joyful

expression were seen by his attendants to overspread the Abbot’s face. In

a few moments the indications of joy were turned into looks of sadness.

Two brethren who attended at the door of his cell inquired the cause. At

first he refused to tell them. He loved them too well to wish to make them

sad. But at last he told them how he had long prayed that at the close of

this thirtieth year he might be relieved from his labours. And this was

the cause of his sudden joy—that he saw angels sent to lead out his spirit

from the flesh. But, again, suddenly he had seen those heavenly messengers

arrested on the opposite shore; and there they were still standing on the

rocks, unable to reach the Holy Isle, because his Lord, who had been

willing to grant that for which he fervently prayed, had yielded to the

more prevailing intercessions of many Churches. And so, those angels were

about to return to the throne above. It was this that had changed his joy.

But now he knew that yet four years longer he must remain; and then

suddenly, and without previous suffering, he would join his Lord.

And so on that fourth year after

this vision, which was A.D. 597, Easter day fell on the 14th April.

On a certain day in the following month, the old Abbot was carried in a

waggon to see his brethren, who were working in the fields on the plain

called the Machar, at the western side of the Island. The road leading to

this plain winds for some distance among rocky knolls, and then opens on

the comparatively level ground, which, being composed of light soil, and

much exposed to the sun, seems to have been then considered the best for

tillage. It was now probably the seed-time of that early husbandry. On

reaching the monks who were engaged in labour, he told them that with

desire he had desired, during the late Paschal commemoration, to join

Christ his Lord; but, that the joy of their festival might not be

converted into mourning, he had been willing that the day of his departure

should yet a little longer be deferred. He then addressed to his saddened

brethren some words of consolation, and, still sitting in the vehicle, he

turned his face eastward to the holy sites, and pronounced a benediction

on the Island and on all its inhabitants. He was then carried back to the

monastery.

It was not many days after this that

on Sunday, during the celebration of the mass, the Abbot’s face was again

seen to be suffused with sudden colour. The old vision had reappeared. An

angel of the Lord, he explained to those about him, was evident to him—

sent to seek for something which was beloved of God, but which still

remained on earth. What that something was he did not say.

On the last day of that week, the

Saturday, Columba went, with his special attendant, Diarmaid, to bless the

Barn or storehouse of the Monastery. He found it so well supplied, that he

told them he rejoiced to see that, although he was about to leave them,

they would not suffer from lack of food. Then turning to Diarmaid, he

said, "This Saturday (the old Sabbath) will be a Sabbath indeed to me; for

it is to be the last of my laborious life, on which I shall rest from all

its troubles. During this coming night, before the Sunday I shall,

according to the expression of the Scriptures, be gathered to my fathers.

Even now my Lord Jesus Christ deigns to call me; to whom, this very night,

and at His call, I shall go. So it has been revealed to me by the Lord."

Having so said, Columba moved from

the Barn, and walked back towards the Monastery. In the middle of the way

he sat down to rest, at a spot which, in Adamnan’s time, was marked by a

cross, and which is very likely indicated by M’Lean’s Cross at the present

day. At that point the old traditional path takes a turn, and begins a

slight ascent. Whilst the Abbot was sitting here, the old white horse

which was wont to carry the milk-pails to the Monastery, is recorded to

have come up to his old master, and, putting its head into his lap, really

seemed to weep. It was after this rest by the wayside that Columba

ascended the Torr-Abb, and uttered that prophecy on the future fame of

lona which has been already quoted. After this he returned to his cell,

and was occupied for some time in his favourite work of transcribing the

Holy Scriptures. He was engaged on the 34th Psalm, and had reached the 9th

verse, and the words, "There is no want to them that fear Him." These

brought him to the foot of the page. "Here," he said, "I must stop. Let

Baithune write out the rest." He then repaired to the church, and attended

the vesper services. Returning to his cell, he lay for some time on his

bed with its stone pillow, which in Adamnan’s time was preserved beside

his tomb. Thence he dictated to his one attendant his last orders to his

brethren. It was in substance the old message which men like Columba give

when the storms of life are over, and when charity and peace are seen to

be the great needs of earth.

After this, Columba lay for a while

in silence, until, called by the matin-bell before the dawn on Sunday

morning—as it has been calculated, the 9th of June,—he rose, and running

before all others, entered the church alone. The building, as the Brethren

approached, seemed to be filled with an angelic light, which, however, had

disappeared ere his attendant entered. "Where art thou, father!’ said

Diarmaid—for the Monks had not yet come with lights, and he had to grope

his way in darkness. There was no reply. Columba was at last found lying

before the altar. Then followed that last scene of all, which so many

generations of men have been called to see—the lifted head, the voiceless

movements, the sinking powers, —all the visible approach of death. A crowd

of weeping Monks, holding up their lanterns, soon stood around the dying

Abbot. Once more his eyes were opened, and visions of glory seemed to pass

before his face. His limbs were now powerless; but his right arm was

raised by Diarmaid. With his hand, although speechless, Columba was still

able to give the sign of Blessing. When this was given, he ceased to

breathe.

Can anything be recalled of the

aspect of that man who then lay dead, now twelve hundred and seventy-three

years ago? Adamnan has preserved many particulars which assure us that

Columba had all those physical characteristics which have a powerful

influence among rude nations. He was of great stature. He had a splendid

voice. It could be heard at extraordinary distances, rolling forth the

Psalms of David, every, syllable distinctly uttered. We are told by his

biographer that his singing, with a very few of his brethren, of the 45th

Psalm, made a profound impression on a Pictish king, whose priests had

attempted to arrest his worship. He had a grey eye, which could be soft,

but which could also be something else. He had brilliant gifts of speech.

With ceaseless energy he worked at all hours in prayer, or in reading, or

in writing, or in some other holy labour. He seemed to have almost

superhuman strength. In vigils and in fasting he was equally

indefatigable. And with all these exercises and labours his countenance

shone with a holy joy—as if in his heart of hearts he was gladdened by the

abiding spirit of his Lord.

Such is the noble picture left us by

Adamnan of Columba’s character and of his appearance. But the details of

his life prove that his character had mellowed and ripened towards its

close. Beyond all doubt his natural disposition was fierce and passionate;

and when he came across deeds of violence or injustice, his indignation

was uttered in terrible denunciations. But he was also affectionate,

grateful, compassionate—easily moved to tears. He is repeatedly described

by Adamnan, as of angelic countenance. In all probability, it was a face,

like the skies of the Hebrides, of various and intense expression.

Perhaps some of those who visit lona

may desire to know the place it occupies in that more ancient History

which was a hidden manuscript in Columba’s days. His voice must often,

indeed, have sounded from before the altar the words of the 95th Psalm:

"The Sea is His, and He made it: and His hands prepared the dry Land." But

it probably never entered into his mind to conceive that man could ever

attain to any knowledge of the methods of creation, or of the steps by

which, through unnumbered ages, the world we live in has been moulded into

the forms we see. Yet this knowledge, in some measure at least, has been

attained.

Iona is entirely composed of strata

which I believe to belong to the oldest sedimentary rock yet known as

existing in the world. That rock is the "Laurentian Gneiss "— so called

from the great area it occupies in the Valley of the St. Lawrence. It was

in this formation that, some years ago, was discovered in Canada a fossil

called the Eozoon Canadense—a name indicating the belief of

Palaeontologists that in this fossil we have a Form belonging to the Dawn

of Life upon our planet. The whole of the Outer Hebrides are composed of

this gneiss, and it is the basement upon which are piled the mountain

ranges of. the northwest coast of Scotland. In lona the formation consists

of a great series of strata, which, from a position originally horizontal,

have been tilted into a "dip" which is nearly vertical. The "strike" of

the beds—that is to say, the direction of their upturned edges— is the

direction of the longer axis of the Island, from north-east to south-west.

The strata are of every variety of character—of slate, of quartz, of

marble with serpentine and of a mixture of felspar, quartz, and

hornblende, which passes frequently into a composition closely resembling

granite. Many of the beds are traversed and permeated by veins and streaks

of a green siliceous mineral which has been called Epidote. Strangers

visiting lona, who have time to do so, should take a boat from the

landing-place to the Port-na-Churaich—the creek where Columba landed. In

passing along this part of the shore with its successive bays and creeks,

a fine view is obtained of the contorted stratification; and the colouring

of the rock near the Port itself, seen through the clear ocean water, is

singularly beautiful. It is, perhaps, vain to speculate, and yet a

geologist cannot fail to do so, as to the nature of those "metamorphic"

agencies which have converted matter, once consisting of soft marine

deposits, into rocks so intensely hard, and so highly mineralised. The

beach of the Port-na-Churaich, which consists of fragments of these rocks

rolled and polished by the surf, is almost like a beach of precious

stones.

The mountains of Mull, seen from

lona, are almost entirely composed of volcanic rocks; yet not a vestige

remains of the volcanic vents out of which those great masses of melted

matter have been poured. In all probability the volcanic action has been

prolonged at intervals through vast periods of time. Some of the trap

mountains of Mull rest on beds of the Old Red sandstone; others of them

are piled on strata of the Oolite and Lias; others, again, cover the

débris of Chalk, and belong to a period more

recent than the middle Tertiaries. In a line between lona and the headland

of Bourg there is a low basaltic promontory, called Ardtun, which has

revealed to us the fact that once there existed on this area some great

country covered with the magnificent vegetation of the warm climates of

the Miocene Age. Nothing of that country or of its vegetation now remains

except a few autumnal eaves sealed up under sheets of lava. The whole of

it has "foundered amidst fanatic storms;" and even of the new surfaces

which arose out of the volcanic outbursts only a few fragments remain,

broken up into capes and headlands and caverned islets in the sea.

From that period there is a great

gap in the geological record, which no man can fill. But at last, far, far

down the stream of Time, one other distinct and legible page of manuscript

has been left! It tells no longer of Fire, but of Ice. To the north of the

Cathedral, not far off, there lies half embedded in the soil of lona a

gigantic boulder of the granite which belongs to the opposite side of the

Sound. It contains more than 200 tons of stone. There is but one agency in

nature which can have transferred that boulder from the opposite coast and

deposited it where it now lies. Two other blocks of nearly equal mass lie

on the other shore, as if they had been arrested on their way, and as if

the icy raft on which they took their passage had failed to carry them

across the ferry. During the Glacial Epoch great masses of ice must have

descended from the mountains of Mull, and pressing over the low promontory

of the Ross, sent floating icebergs to lona, and to the open sea.

Those who walk to the north end of

lona, or those who pass it by sea, will observe a tract of blowing sand

almost as white as snow. The origin and the effects of this sand are

curious, and are among the many illustrations which nature affords of the

power of small operations carried on unceasingly through long periods of

time. It occupies comparatively a small space upon Iona; but on some of

the other Hebridean Islands it covers many hundred acres. It is entirely

composed of the pulverised shells of two or three species of small

land-snails, particularly Helix virgata, and Helix cafterata,

and Bulimus acutus These species live and die in such countless

myriads on the short clover pastures near the sea, that their fragile

shells, yearly accumulating, gradually raise the surface of the soil,

until it attains a depth of several, sometimes of many, feet. So long as

no break of surface occurs, the grasses and clovers which flourish on it

make it useful pastureland— although there seems to be hardly any mixture

of earthy matter. But when the wind once effects a breach in the turf, the

light powdery material below is driven like snowdrifts before the gale—and

this process (unless it be stopped by artificial means, such as planting

bent-grass, and turfing over the broken surfaces) goes on until the whole

is blown away, and the bare rock or gravel which may lie below alone

remains. Then the cycle of operations begins anew—a few hardy grasses skin

over the stony surface— the snails again begin to multiply and die— until

again a calcareous soil is formed. But in the meantime the drifted

material has, perhaps, overwhelmed whole farms of better soil, and

converted them into a wavy waste of loose and barren sand. This calamity

has happened in Tyree; and one ancient church, with its burying-ground,

may be seen deserted in the middle of an absolute waste.

From these few words of description,

it will be seen that Iona itself; and the view from it, present to the eye

or to the mind at once some of the surest results and some of the most

difficult problems of geological science. There are proofs of the

succession of Life through ages which are vast and indefinite, but which

are not illimitable. There are, or there seem to be, "traces of a

beginning." But, on the other hand, there is the question raised whether

this apparent dawn is a real dawn, or whether the absence of higher

organisms be not due to subsequent obliteration. There is the certainty of

a definite order of events in the redistribution of Sea and Land, and of

whole cycles of change in the climates and in the productions of the

globe. But how those changes were brought about, and whether the agencies

producing them were always slow and gradual, or frequently sudden and

violent— all this is hidden in the thickest darkness. There is visible

demonstration that even the most enduring forms of nature round us are of

very recent date, and that it is only in comparison with the spanlike

shortness of human life that we can speak of the "everlasting Hills." But

how those Hills were raised, and their shapes determined, and the valleys

formed, and the broken remains of older lands scattered among the

waves—these are questions on which we can only speculate, and speculate

perhaps in vain.

The Magnitudes of Space and Time are

too often felt as oppressive to the human spirit. Yet in the inspired

utterances of the Old Testament they are regarded, not indeed without

emotion, but without dismay. The Prophets of Israel seem to have felt all

that we can feel of the vastness of Nature. It moved them to exclaim,

"What is man?" but it did not shake the faith with which they added, "That

Thou art mindful of him." And this triumphant faith is in harmony with

reason and with science. The Mind which is able to conceive those

Magnitudes of Space and Time, and which indeed is unable to conceive

either any limit of Space or any end of Time, is itself the greatest

Magnitude of all. We see and know that its appearance in the world has

been the crown and consummation of creative ages. Every fact which

concerns its history and its destinies is of a different and a higher

order of interest than any other fact which concerns only the preparation

of its abode. If the mere bigness, or the mere age of things, were the

measure of interest attaching to them, then the arrival of the granite

boulder on its floe of ice was a far more important event than the arrival

of Columba in his boat of hides. The boulder still lies where it lay for

thousands of years before his time. Columba’s body has been resolved into

indistinguishable dust. But what he did and said has acquired a permanent

place in the history of that Being for whom the Sea has been made and the

dry Land "prepared." The years cannot be counted which elapsed between the

deposit of the Laurentian Gneiss and the close of the Glacial epoch.

Certain it is that, compared with them, all the years of Man’s history are

few indeed. Yet half the years of a single human life have conferred upon

Iona its imperishable fame; and once more standing on the Abbot’s Mound,

we may repeat with him the words of that prophecy which has been, and is

being still, fulfilled:

HUIC LOCO, QUAMLIBET ANGUSTO ET VILI,

NON TANTUM SCOTORUM REGES, CUM POPULIS, SED ETIAM BARBARARUM ET EXTERARUM

GENTIUM REGNATORES, CUM PLEBIBUS SIBI SUBJECTIS, GRANDEM ET NON MEDIOCREM

CONFERENT HONOREM: A SANCTIS QUOQUE ETIAM ALIARUM ECCLESIARUM NON

MEDIOCRIS VENERATIO CONFERETUR.

THE END