|

FROM a rapid view of Columba’s time,

let us pass to a closer inspection of Columba’s Home. We have seen the

place which his age occupied in the history of the world, and the

character of those events in which he bore a part, or of which he must

have heard the fame. Let us now visit the Island which is sacred to the

memory of his illustrious life, and look upon the landscape which was

familiar to his sight. Dr. Johnson, in a celebrated passage, has condemned

the "frigid philosophy" which could regard with-out emotion the scenes

which are associated with the triumph of piety or of learning; and yet in

many cases those scenes are so wholly changed that nothing of identity

remains except mere geographical position. The places where great men or

great communities have flourished and decayed, and which now "know them no

more for ever," would often be as little recognized by them, if they were

to rise again from the dead. The learned historian of "Latin Christianity"

speaks of the beauty of the situations which were invariably chosen by the

Benedictine Monks for the monastic sites in England. But when the

structure of a country is comparatively level, almost everything which is

characteristic in the landscape depends upon features which change in the

course of a very few generations. It depends on the progress of

enclosures, on the distinctive colouring of cultivated and uncultivated

ground, on the disappearance of forests, on the new disposition of woods

and trees. In such situations nothing that we see now may be as it was

seen by those whose memory has brought us to the spot. With lona the case

is very different. We may be sure that what we now see is very much what

Columba saw. Its distinctive features depend upon the enduring Hills, and

upon the still more enduring Sea. To the eye of a geologist, indeed, I

know very few situations where every outline tells so distinctly of the

most tremendous agencies of change—of volcanic heat and of glacial cold,

of upheaval and of subsidence, of rupture and of abrasion, and of the

waste of time. But all these agencies, except the last, have been so long

at rest that the human race has been slow to believe in their existence.

It is, indeed, the most difficult of all things to form any distinct

conception of the nature and the method of their works, or of the part

which each of them has had in moulding and con-figuring the world we see.

And, as regards the waste of time, not only all the centuries since

Columba’s birth, but all the centuries since the birth of man, are but "as

yesterday when it is past, or as a watch in the night." The Ocean has been

called, by Hugh Miller, "that blue foaming dragon, whose vocation it is to

eat up the land :" but the rate at which it eats up the Hebridean rocks is

very slow indeed. The singular and beautiful clearness of its waters round

those shores is a sufficient proof how infinitesimally small is the amount

of spoil. Nothing, therefore, can be more certain than that, when we look

upon lona, or when we range even the wide horizon which is visible from

its shores, we are tracing the very outlines which Columba’s eye has often

traced, we follow the same winding coasts and the same stormy headlands,

and the same sheltered creeks, and the same archipelago of curious

islands, and the same treacherous reefs—by which Columba has often sailed.

A few changes, of a very superficial kind, may have been brought about.

Forests can never have flourished on those outward slopes which front the

Atlantic blasts. But some shaggy brushwood has doubtless disappeared,— the

introduction of sheep has made the pastures greener—to some extent the

heather has given way to grass. But this is the whole amount of change.

All the great aspects of nature upon and around Iona must be the same as

they were thirteen hundred years ago.

What, then, are those aspects? To

Montalembert they are all mournful and oppressive. He paints the landscape

in the gloomiest colours. Its picturesqueness, he says, is with-out charm,

and its grandeur is without grace. The neighbouring isles are all naked

and desert. The mountains are always covered with clouds, which conceal

their summits. The climate is one of continual mists and rains, with

frequent storms. The "pale sun of the north," when it is seen at all,

gleams only upon dull and leaden seas, or upon long lines of melancholy

foam. Those who know the Western Isles know how unreal all this sort of

language is. The appreciation of natural beauty in its various forms

depends mainly upon association, very little upon knowledge or upon

conscious thought. The scenery of the Hebrides is altogether peculiar, and

to those whose notions of beauty or of fertility are derived from

countries which abound in corn and wine and oil, the charms of that

scenery can perhaps never be understood. And yet these charms are founded

on a wonderful combination of the three greatest powers in nature—the Sky,

the Sea, the Mountains. But these stand in very different relations to the

early memories of our races. As regards the Sky there is no speech or

nation where its voice is not heard; there is no corner of the world where

the sweet influences which it sheds do not form, consciously or

unconsciously, an intimate part of the life of men. But it is not so with

the Ocean. There are millions who have never seen it, and can have no

conception of the aspect of the most wonderful object upon earth. To many

who have seen it, it inspires nothing but dislike. By the Prophet of

Patmos,—although no image is more frequent in his visions as an emblem of

glory and of brightness,—the Ocean is classed in a sublime passage along

with Death and Hell, as among the Holders of the Dead (Rev. xx 13).

And so, in this character at least, we are told that it is to have no

place in the New Heavens and the New Earth, where "there shall be no more

Sea" (Rev. xxi. 1). The gentle spirit of Mrs. Hemans was troubled by the

same aspect of the Ocean, and few more touching verses have been left us

by her pen than those which she addressed to the "hollow-sounding and

mysterious Main:

"To thee the love of woman bath gone

down,

Dark flow thy tides o’er manhood’s noble head."

The feeling is natural, and, like so

many others connected with the dead, we find it enshrined in "In

Memoriam:"-

"O to us,

The fools of habit, sweeter seems

"To rest beneath the clover sod,

That drinks the sunshine and the rains,

Or where the kneeling hamlet drains

The chalice of the grapes of God,

"Than that with thee the roaring

wells

Should gulf him fathom deep in brine,

And hands so often clasped in mine

Should toss with tangle and with shells."

But, after all, the Ocean is

something more than a "vast and wandering grave." Its associations are not

mainly with the Dead. Neither is it the only power which seems to

dissipate beyond recovery this Tabernacle of the Flesh. The question,

"With what Body do they come?" is asked more often of the Forms which have

been returned to the dust of Earth than of those which have been lost in

many water’s. To eyes that have been accustomed to rest upon the boundless

fields of Ocean, there is nothing in nature like it. The inexhaustible

fountain of all the fertility and exuberance of earth—the type of all

vastness and of all power—it responds also with infinite subtlety of

expression to every change in the face of heaven. There is nothing like

its awfulness when in commotion. There is nothing like its restfulness

when, it is at rest. There is nothing like the joyfulness of its reflected

lights, or the tenderness of the colouring which it throws in sunshine

from its deeps and shallows. I am sorry for those who have never listened

to, and therefore can never understand, the immense conversation of the

Sea.

Of the third great power in

landscape—of the Mountains—there is less need to speak. This at least is

more generally understood. There are not many places in the world where

those three great voices—" each a mighty voice"—the Sky, the Sea, the

Mountains—can be heard sounding in finer harmony than round Columba’s

Isle. It is true that the climate of the Hebrides is a wet one; and hence

the perennial verdure which flourishes to the very summits of the hills,

in happy contrast with the absolute sterility of a great proportion of all

the mountain ranges in the south of Europe. Hence also the wonderful

beauty of the skies. "Cloudland, gorgeous land," is a truthful exclamation

of the poet. For nowhere is the face of heaven more various in expression

than along that line of coast where the vapours of the Atlantic are first

caught by the Highland hills. Byron’s famous lines, in which he touches on

the difference between the sunsets of the south and of the north, give by

no means an accurate idea of that in which the difference really consists.

I have seen from Athens "morning spread upon the mountains" along the

opposite range of Parnes, and the low sun streaming up the Gulf of Corinth

upon the hills of the Morea. Those tints are certainly beyond measure

beautiful. But the sunsets which are to be seen constantly among the

Western Isles are not, as compared with those of the Mediterranean,

"obscurely bright." It is true the colouring is darker, but it is also

deeper—richer—more intense. Nothing indeed can exceed its splendour. And

so of the Sea: its aspects around lona are singularly various and

beautiful. On one side is the open Ocean, with nothing to break its fetch

of waves from the shores of the New World. On the other side, it is

divided into innumerable creeks and bays and inlets, which carry the eye

round capes and islands, and along retreating lines of shore far in among

the hills. Its waters are exquisitely pure—of a luminous and transparent

green, shading off into a rich purple—where the white, sandy bottom is

occupied by beds of Alga. Into these greens and purples on the opposite

side of a narrow Sound, dip granite rocks of the brightest red. Then there

is the busy population of the teeming Sea—its shoals of fish—its great

mammalia, which are the hugest of living things—its snowy and its swarthy

birds, with all the movement of their wings, the arrowy flight of the wild

Rock Pigeon (the origin of all our domestic doves), and the occasional

sweep of the Peregrine. Whatever a modern Frenchman— even a man of genius

like Montalembert— may think of such things as these, there is every

reason to believe that they were not repugnant to Columba. He was an Irish

Celt. His own early home was in the wilds of Donegal, where the climate is

not less weeping, and where a coast of far more frowning aspect fronts the

Atlantic Ocean. Some poems in the Erse language have been handed down as

written by Columba; and although they may not be actually his, they are at

least very ancient, and represent the kind of imagery which was familiar

to his race, and those aspects of nature in which they took delight. There

is no melancholy moping over the Sea because it is not always blue, nor

over rocks and mountains because they are not rich in foliage.

"Delightful to be on Benn-Edar,

Before going o’er the white sea:

The dashing of the wave against its lice,

The bareness of its shore and its border.

"Delightful to be on Benn-Edar,

After coming o’er the white-bosomed sea,

To row one’s little coracle,

Ochone! on the swift-waved shore.

"How rapid the speed of my coracle,

And its stem turned upon Derry:

I grieve at my errand o’er the noble sea

Travelling to Alba of the Ravens.

* * * * *

Beloved to my heart also in the West,

Drumclift at Culcinne’s strand:

To behold the fair Loch Feval,

The form of its shore; is delightful.

"Delightful is that, and delightful

The salt main on which the seagulls cry

On my coming from Deny afar;

It is quiet, and it is delightful.

Delightful."

Reeve’s "Adanman," p. 285-9.

Columba may indeed have missed the

"oaks of Derry," and that intense love of place which is a passion with

the Celt doubtless made all lands but Erin appear to him as lands of

exile. But if his eye rested with delight on the "dashing of the wave,"

and on the "form of shores," no spot could have been better chosen than

that on which he lived and died.

lona is situated at the southern

apex of that long triangular tract of mountain-land which lies to the

north-west of the great Caledonian valley, and which, stretching from

Inverness on the one side, and from Cape Wrath on the other, terminates in

the lofty summit of Ben More, in Mull. In approaching lona along the south

coast of Mull, we see the massive hills of igneous rocks which constitute

the great bulk of that large Island, subsiding somewhat suddenly into a

long promontory of comparatively low elevation, at first with sharp and

broken outlines, due to mica slate, and then with rounded knobs and knolls

of granite, swept naked by the blast along the margin of the sea, but

farther inland covered with sheets of moss and heather. Off the point of

this long promontory, called the Ross, and separated from it by a Sound of

shallow sea about one mile broad, lies Columba’s Isle.

The causes which determined Columba

in his selection of Iona are not mysterious. Some of them have, been

preserved in traditions, which are as poetical as they are probably true;

whilst others are obvious on a moment’s consideration of the position and

of the character of the spot. In the first place, it was an Island; and

Islands have been always popular with the Monastic Orders. They give

seclusion, and, with seclusion, they afford facilities for the enforcement

of discipline. Is it wrong to conjecture, also, that they satisfy that

sense of possession which lies deep in human nature, and which has made

even hermits rejoice in some rock which they could call their own? And

then comes that ground of preference which has lived in the. memory of the

place for thirteen hundred years, and which must be true, for it stands in

unmistakeable harmony with the earlier events of Columba’s life, and with

a natural character which was full of strong and fierce emotions. He had

been the cause—and by no means the innocent cause—of war and bloodshed in

his native land. It was the censures of the Church and the contrition of

his own soul which drove him ‘into exile, and to the undertaking of some

great labour in the cause of Christ. But the passionate love of an Irish

Celt for his native Ireland seems to have burned in him with all the

strength which is part of a powerful character. It is most true to

nature—that which is related in the memories of his race—that he could not

bear to live out of Ireland and yet within sight of her shores. On his

voyage northwards in his boat of hides, he must have passed many islands—Islay

first, but that, probably, was too large and too near; Jura next, but this

also was no place for a hermitage, and the rocks of Antrim were still too

close at hand. Colonsay, with its little outlying islet, Oronsay—here was

an island of the fitting size. Columba landed; but on his ascending the

heights, the blue land of Erin was still above the Sea. On, then,

northwards, once more; and, as the same old poem represents him saying—

"My vision o’er the brine I stretch

From the ample oaken planks;

Large is the tear of my soft gray eye

When I look back upon Erin."

The next land he touched was the

land which he has made his own. If he landed, as no doubt he did, at the

spot which continuous tradition has pointed out, he cannot have known, or

he must have missed, the entrance to the Sound. Passing through a

labyrinth of rocks, his boat was received into a creek which to this day

retains the name of the "Port of the Coracle" (Port-na-Churaich)—a port

guarded round by precipitous rocks of gneiss, and marked by a beach of

brilliantly coloured pebbles of green serpentine, green quartz, and the

reddest felspar. Again he mounted the nearest hill, and here at last the

southern horizon was nothing but a line of Sea. And so this hill has ever

since been marked by a cairn, which is known to the Gael as "Cairn cul ri

Erin," or, the "Cairn with the back turned upon Erin." Farther exploration

must soon have discovered to Columba that the Island on which he had now

landed had other and more substantial recommendations. On the eastern side

was the channel which he had missed, giving much-needed shelter from

prevailing winds. Above all, it was—

pace Montalembert — a fertile Island,

giving promise of ample sustenance for man and beast. It is true lona is a

rocky island, the bones protruding at frequent intervals through the skin

of turf. Even there, however, Columba must have seen that the pasture was

close and good; and not far from the spot on which he first swept the

southern sky, he must have found that the heathy and rocky hills subsided

into a lower tract, green with that delicious turf which, full of thyme

and wild clovers, gathers upon soils of shelly sand. This tract is called

in Gaelic, "The Machar," or Sandy Plain. A little farther on, he must soon

have found that the eastern or sheltered side presented a slope of fertile

soil, exactly suiting the essential conditions of ancient husbandry. At a

time when artificial drainage was unknown, and in a rainy climate, the

flats and hollows which in the Highlands are now generally the most

valuable portions of the land, were occupied by swamps and moss. On the

steep slopes alone, which afforded natural drainage, was it possible to

raise cereal crops. And this is one source of that curious error which

strangers so often make in visiting and in writing on the Highlands. They

see marks of the plough high up upon the mountains, where the land is now

very wisely abandoned to the pasturage of sheep or cattle; and, seeing

this, they conclude that tillage has decreased, and they wail over the

diminished industry of man. But when those high banks and braes were

cultivated, the richer levels below were the haunts of the Otter, and the

fishing places of the Hern. Those ancient plough-marks are the sure

indications of a rude and ignorant husbandry. In the eastern slopes of

lona Columba and his companions found one tract of land which was as

admirably adapted for the growth of corn as the remainder of it was suited

to the support of flocks and herds. On the north-eastern side of the

Island, between the rocky pasturage and the shore, there is a long,

natural declivity of arable soil steep enough to be naturally dry, and

protected by the hills from the western blast.

And so here Columba’s tent was

pitched, and his Bible opened, and his banner raised for the conversion of

the heathen.

The ancient ecclesiastical buildings

which are now slowly mouldering to decay, and which are all grouped within

a short distance of each other, mark beyond all question the few acres of

ground on some part of which Columba’s cell and church were built. And yet

the first thing we must do in standing on the spot is to imagine it

denuded of all these buildings. They have their own interest and their own

beauty. But one and all of them belong to a very different age from that

in which Columba lived. One of them—the least and the most inconspicuous,

but the most venerable of them all—St Odhrain’s Chapel, may possibly be

the same building which Queen Margaret of Scotland is known to have

erected in memory of the Saint, and dedicated to one of the most famous of

his companions. But Queen Margaret died in A.D. 1092, and therefore any

building which she erected, must date very nearly five hundred years after

Columba’s death; that is to say, the most ancient building which exists

upon Iona must be separated in age from Columba’s time by as many

centuries as those which now separate us from Edward III.

But St. Odhrain’s Chapel has this

great interest—that in all probability it marks the site of the still

humbler church of wood and wattles in which Columba worshipped. There are

some things for which tradition may be safely trusted. The succession of

generations among men has been compared to leaves of the forest; but,

unlike forest-leaves, which all die about one time, and reappear at

another time after a long interval that cuts off the seeming continuity of

life, the generations of mankind are renewed from day to day and from year

to year; so that the young hold fast the memories of the old, and that

which was dear to the fathers is dear to the children also. And thus it is

difficult to conceive that the site of Columba’s church could ever have

been forgotten. It must have been always a sacred spot. Nor is it probable

that when Queen Margaret built, she would leave the place which was

hallowed by associations so dear to her. We are indeed expressly told by

the annalist from whom our information in this matter is derived, that

Queen Margaret’s work was a restoration of St. Columba’s church, which had

fallen into decay. But if there be any doubt as to the identity of that

spot, there is none as to another spot which is close at hand. This is the

"Reilig Odhrain," the ancient burying-place of lona. Among the tenacious

affections of the Celt, there is none more tenacious than that which

clings to the place which is consecrated to the Dead. Hither, during more

than a thousand years, were carried Kings and Chiefs, even from the

far-off shores of Norway, with other men of high and low degree, that

their bodies might mingle with the dust of the Holy Isle. And close beyond

the Reilig Odhrain, a little to the north-east, and nearly opposite to the

western front of the cathedral church, there is a natural hillock of rock,

but covered on most sides by turf, which is perhaps the most interesting

spot upon lona. From its isolated position—from its close proximity to St.

Odhrain’s chapel, and to the ancient place of sepulture—from its rising

beside the old path which runs along the foot of the rocky hills, and

divides them from the cultivated grounds—from the splendid view it

commands over the sacred objects close at hand, over the sloping fields,

the Sound, the opposite coast, and the distant mountains,—this knoll must

have been a favourite resort of all the generations of men who lived and

worshipped on lona. Tradition, too, has faithfully preserved in its Gaelic

name the identity of the spot. It is called the "Torr-Abb," or the

"Abbot’s Knoll." I cannot doubt that it is "the little hill" respecting

which Adamnan gives perhaps the most remarkable anecdote in his account of

Columba’s life. On the last day of that life, Columba, we are told, being

now very infirm, ascended a "little hill" (Monticellulum) which overlooked

the Monastery and here, standing for a short time upon the top, and

lifting up both his hands, he blessed his now long-adopted home, and he

pronounced this prophecy of its fame: "Unto this place, albeit so small

and poor, great homage shall yet be paid, not only by the Kings and people

of the Scots, but by the rulers of barbarous and distant nations, with

their people also. In great veneration, too, shall it be held by the holy

men of other churches." Considering that this prophetic benediction was

recorded within the lifetime of men who had seen Columba, and considering

the long course of later centuries through which it has been literally

fulfilled, we cannot doubt that this is one of the many instances in which

men who have left their mark upon the world have exhibited a proud and

grateful consciousness of the life they were yet to live when dead, in the

memory of mankind. But St. Odhrain’s Chapel has this

great interest—that in all probability it marks the site of the still

humbler church of wood and wattles in which Columba worshipped. There are

some things for which tradition may be safely trusted. The succession of

generations among men has been compared to leaves of the forest; but,

unlike forest-leaves, which all die about one time, and reappear at

another time after a long interval that cuts off the seeming continuity of

life, the generations of mankind are renewed from day to day and from year

to year; so that the young hold fast the memories of the old, and that

which was dear to the fathers is dear to the children also. And thus it is

difficult to conceive that the site of Columba’s church could ever have

been forgotten. It must have been always a sacred spot. Nor is it probable

that when Queen Margaret built, she would leave the place which was

hallowed by associations so dear to her. We are indeed expressly told by

the annalist from whom our information in this matter is derived, that

Queen Margaret’s work was a restoration of St. Columba’s church, which had

fallen into decay. But if there be any doubt as to the identity of that

spot, there is none as to another spot which is close at hand. This is the

"Reilig Odhrain," the ancient burying-place of lona. Among the tenacious

affections of the Celt, there is none more tenacious than that which

clings to the place which is consecrated to the Dead. Hither, during more

than a thousand years, were carried Kings and Chiefs, even from the

far-off shores of Norway, with other men of high and low degree, that

their bodies might mingle with the dust of the Holy Isle. And close beyond

the Reilig Odhrain, a little to the north-east, and nearly opposite to the

western front of the cathedral church, there is a natural hillock of rock,

but covered on most sides by turf, which is perhaps the most interesting

spot upon lona. From its isolated position—from its close proximity to St.

Odhrain’s chapel, and to the ancient place of sepulture—from its rising

beside the old path which runs along the foot of the rocky hills, and

divides them from the cultivated grounds—from the splendid view it

commands over the sacred objects close at hand, over the sloping fields,

the Sound, the opposite coast, and the distant mountains,—this knoll must

have been a favourite resort of all the generations of men who lived and

worshipped on lona. Tradition, too, has faithfully preserved in its Gaelic

name the identity of the spot. It is called the "Torr-Abb," or the

"Abbot’s Knoll." I cannot doubt that it is "the little hill" respecting

which Adamnan gives perhaps the most remarkable anecdote in his account of

Columba’s life. On the last day of that life, Columba, we are told, being

now very infirm, ascended a "little hill" (Monticellulum) which overlooked

the Monastery and here, standing for a short time upon the top, and

lifting up both his hands, he blessed his now long-adopted home, and he

pronounced this prophecy of its fame: "Unto this place, albeit so small

and poor, great homage shall yet be paid, not only by the Kings and people

of the Scots, but by the rulers of barbarous and distant nations, with

their people also. In great veneration, too, shall it be held by the holy

men of other churches." Considering that this prophetic benediction was

recorded within the lifetime of men who had seen Columba, and considering

the long course of later centuries through which it has been literally

fulfilled, we cannot doubt that this is one of the many instances in which

men who have left their mark upon the world have exhibited a proud and

grateful consciousness of the life they were yet to live when dead, in the

memory of mankind.

Standing on this old rocky mound, we

can re-animate the scene with very tolerable correctness, as it must have

appeared in Columba’s life. It is certain that the buildings of his time

were all of wood. Probably some external plaster covered the timbers and

the wattled walls of which they were constructed. Like all other works of

man, the edifices in which we live, and those also in which we worship,

have had their forms determined by a process of development that is to

say, by gradual modifications of rude and early types. It is exceedingly

probable that in the very old and ruined stone chapels of the Highlands,

we see something not unlike the shape and proportions of the wooden

structures of the Columban age. The form is that of a low and simple

quadrangular building with steep roof. The brethren of the community lived

each in separate huts or "cells," constructed of the same materials. There

was some provision for strangers, who often, though not probably in great

numbers at one time, were attracted to the place. There was a refectory

for the common meal. Columba’s own abode was erected on a rising ground

above the rest. Some brethren attended to the cattle, to the milking of

cows on distant pastures, and to bringing home the produce in dosed wooden

vessels carried upon horseback. Others tilled the soil for the raising of

oats and barley. There seems to have been an abundant dairy, a well-stored

granary, and by no means a deficient larder. The island now supports

upwards of 200 cows and heifers, 140 younger "beasts," about 600 sheep and

lambs, 25 horses, and some three-score of the pachyderms so dear to all

the children of Erin. It grows also a considerable quantity of grain. But

even these resources, ample as they might seem to be, were not enough for

the growing number of the Columban monastery. Very soon royal grants of

neighbouring islands made them tributary to the sustenance of the Abbot

and his brethren, and foremost among these came the productive

corn-bearing soil and the rich pastures of Tyree. Fish were abundant and

could be obtained at all seasons. The large flounders of the Sound of lona

are still an important item in the diet of its people. The rocks and

islets all around swarmed with Seals, and their flesh seems to have been a

favourite article of food. Their oil, also, doubtless supplied the light

with which, during many long winter evenings, Columba pored over his

manuscripts of the sacred text, or performed midnight services before the

altar.

With all these various occupations

there must have been constant life and movement both on land and sea. Nor

must we forget Columba’s own frequent embarkations - sometimes only in

little boats to cross the Sound, or to visit those adjacent islands, some

of which were soon colonized from the parent Monastery; sometimes in

larger vessels, starting on some distant expedition, to preach among the

heathen Picts. Columba and his brethren must have been skilled and hardy

seamen. How often from this very hill must the monks have watched for

their Abbot’s returning barque—rounding the red rocks of Mull from the

southward, or speeding with longer notice of approach from the north. From

the same spot, we may be sure, has Columba often watched the frequent

sail—now from one quarter, now from another, bringing strange men on

strange errands, or old familiar friends to renew the broken intercourse

of youth. Hither came holy men from Erin to take counsel with the Saint on

the troubles of clans and monasteries which were still dear to him. Hither

came also bad men red-handed from blood and sacrilege to make confession

and do penance at Columba’s feet. Hither, too, came Chieftains to be

blessed, and even Kings to be ordained—for it is curious that on this

lonely spot, so far distant from the ancient centres of Christendom, took

place the first recorded case of a temporal sovereign seeking from a

minister of the Church what appears to have been very like formal

consecration. Adamnan, as usual, connects his narrative of this event,

which took place in 547, with miraculous circumstances, and with Divine

direction to Columba, in his selection of Aidan, one of the early Kings of

the Irish Dalriadic colony in Scotland.

The fame of Columba’s supernatural

powers attracted many and strange visitors to the shores on which we are

now looking. Nor can we fail to remember, with the Reilig Odhrain at our

feet, how often the beautiful galleys of that olden time came up the Sound

laden with the Dead,—"their dark freight a vanished life." A grassy mound

not far from the present landing-place is known as the spot on which

bodies were laid when they were first carried to the shore. We know from

the account of Columba’s own burial that the custom was to wake the body

with the singing of psalms during three days and nights before laying it

to its final rest. It was then borne in solemn procession to the grave.

How many of such processions must have wound along the path that leads to

the Reilig Odhrain! How many: fleets of galleys must have ridden at anchor

on that bay below us, with all those expressive signs of mourning which

belong to ships, when Kings and Chiefs who had died in distant lands were

carried hither to be buried in this holy Isle! From Ireland, from

Scotland, and from distant Norway, there came, during many centuries, many

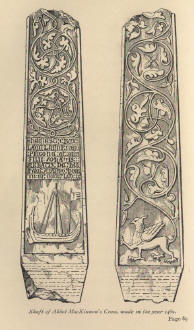

royal funerals to its shores. And at this day by far the most interesting

remains upon the Island are the curious and beautiful tomb-stones and

crosses which lie in the Reilig Odhrain. They belong, indeed, even the

most ancient of them, to an age removed by many hundred years from

Columba’s time. But they represent the lasting reverence which his name

has inspired during so many generations, and the desire of a long

succession of Chiefs and warriors through the Middle Ages and down almost

to our own time to be buried in the soil he trod. |