A SHIELING is a quiet, dreamy thing;

and the memories of hours and days passed at an

island shieling are as fresh and as fragrant as the winds that are wont to

blow over a June garden at noontide.

The old-fashioned agricultural methods which still

obtain in the Western Isles certainly have their disadvantages in this age

of opulence and ugliness, because the little croft is no longer what we

would term an economic unit in the modern sense. And so all the minor

activities associated with it must be earnestly and diligently attended to

if the crofter, whose lot under present circumstances seldom errs on the

side of ease and comfort, is to make ends meet at all. His return is

invariably small and disappointing; and, if he means to accumulate a

little produce in his mean store-house, so as to tide him over the cold,

wet winter months, he must needs labour exceedingly hard on a soil which

is as barren as it is cumbersome to till.

And yet those whom from the lone shieling and the misty

island mountains divide, and a waste of seas, never forget their

island-homes and the memories of their peat-reeked shielings.

Cattle left to graze in a large, fenced enclosure may

give little labour and anxiety, because they cannot go astray and need not

be attended to except at regular intervals; but the well-fenced farm

possesses neither the poetry nor the interest of a Hebridean shieling,

where there are no fences, and only a few dilapidated dykes here and

there. As a rule, however, there are no boundaries for miles and miles,

and one can wander on indefinitely without seeing any signs of a dyke

where two or more common grazings may impinge upon one another.

In Gaelic the shieling is called an airidh.

Strictly speaking, it refers to the driving of the cattle to the hills in

the early summer, and remaining there with them during the warm months,

for, when they have cropped the grazing grounds nearer home, it becomes

necessary to take them where pasturage is rich and more plentiful. After

the summer is over, the cattle are again driven home to their respective

townships.

It is the young women who usually accompany them to the

shieling, because they are better adapted to the work connected with cows,

such as milking and the making of cheese and butter. At night the women of

the shieling shelter in little huts scattered here and there on the moor.

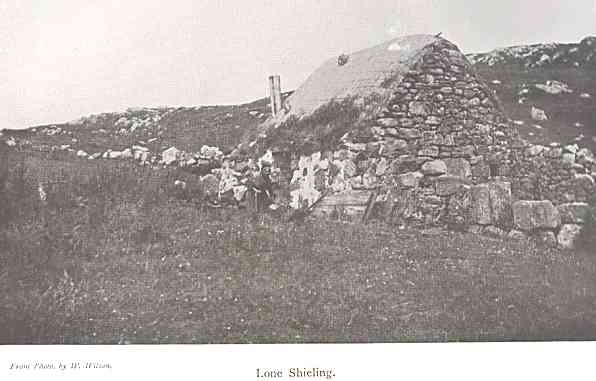

These summer homes are constructed of turf or of stone, because,

unfortunately, many of the islands are entirely wanting in trees.

A shieling house is as simple and unpretentious within

as it is without, for the women-folk only bring with them such necessary

utensils as may be required in the preparation of their food. Of course,

they take with them milk-pails and churns, and cogues, and cheese vats,

and such like things; but ordinary household furniture at a shieling can

be dispensed with. The seating requirements, for example, are often

supplied by a plank stretched between a couple of large, flat stones;

while meals are eaten at a readily improvised table.

The fire is of peat, and is laid on the floor. It is

never allowed to go out because, when it is not needed for cooking

purposes, a few peats are placed on it, and it is left to smoulder away

quietly. As every one is aware, a peat fire will keep in for hours if not

disturbed; and it is easily kindled when attended to. There is seldom any

scarcity of fuel at the shieling, for the peat-moss is often within a

short distance; and indeed it is customary to cut and stack peats at

shieling-time, and to build a small heap of peats on the leeward side of

the shieling hut, so that an adequate supply is always ready at hand. It

may be of interest to you to know that in some of the Islands it is usual

for one member of the party to carry a smouldering peat all the way from

the township, in order that the fires may be lit from it on arrival at the

shieling.

There are, as a rule, no feather mattresses and pillows

at a shieling; the beds are made of fragrant heather and bracken, and

sometimes of dried moss gathered around the door of the hut. During the

day the maidens of the shieling are engaged in making dairy produce, or in

watching the kye lest they should wander away across the moors. Their idle

moments are occupied in preparing wool, or at the spinning-wheel. These

are the scenes from which many of our most beautiful melodies have

emanated, for the Hebridean weavers and spinners are wont to sing at their

work.

At the shieling even the tiresome duty of washing-up

after meals is made easier, because this can be done in a ready fashion at

the little mountain-stream near-by, from which the shieling receives its

water-supply.

It ought to be mentioned, too, that while the women and

children are absent at the shieling, the men who are not at the fishings

are busily repairing the thatch, and otherwise redding up the crofts in

preparation for the winter storms.

In bygone days some parts of the Hebrides were noted

for their shielings. Dean Munro, who travelled through most of the Islands

about the close of the sixteenth century, tells us of the shieling on the

Island of Lingay. ‘Narrest to Gigay,’ he writes, ‘lyes ane ile callit

Lingay haffe a myle lange ane verey guide ile for gressing, pastures, and

for a shieling, appertaining to the M’Neill of Barray.’

Raasay long ago was famous for its shieling; and Martin

tells us that the islanders flocked thither with their families in the

summer-time for conveniences of grazing and fishing, and sought shelter in

the great caves on the west side of the Island, having been able thus to

dispense with turf-built huts.

A shieling in Uist in the fifteenth century

was remarkable not only on account of the

excellent summer pasturage it afforded, but also because the deep valley

in which it lay was reputed by the natives to be haunted by ghosts, whom

they called the ‘Great Men.’ This belief still lingers among many homes in

the neighbourhood. In the olden days it was held that whatsoever man or

woman entered the valley without having first completely resigned himself

or herself, would assuredly go mad. Those who were accustomed to sojourn

there renounced their claims to earthly things by repeating a short

invocation to the ‘Great Men’ who ‘spirited’ the valley, and under whose

guidance and protection they immediately placed themselves upon entering.

When Martin visited Uist he tried hard to persuade the

inhabitants to abandon this silly piece of credulity, explaining to them

that their imaginary protectors were deserving of no such extravagance.

But they assured him that their belief had been confirmed by a woman who

entered the valley unawares and instantly became mad, having failed to

resign herself. He tells us, too, that the Protestant minister often

endeavoured to expose their deception but without avail, partly because of

the implicit trust they had in their priest, but chiefly because ‘when

topics of persuasion, though never so urgent, come from one they believe

to be a heretic, there is little hope of success.’

The shieling which is in my mind as I write is situated

in the Lews, far away among the Bens of Barvas. I want you to imagine

yourself there on a midsummer day, surrounded by warmth and sunshine and

peacefulness, where

Bog myrtle swings across the dreamy hour,

Its noontide fragrance like an incensed flower.

Picture yourself lolling around a shieling hut where a

lovely sheep-collie basks in the sunlight at the doorstep; and imagine

that the soft breezes are filling your nostrils with the scent of gorse

and clover and sweet grass. Such is the atmosphere of a Hebridean shieling

on a summer day.

But to appreciate a shieling to the fullest one ought

to visit it as the daylight fades and the sun dips low beneath the hills,

for it is then that the cattle softly wend their way across the sleepy

moor, because milking-time draws near.

The shieling is often in the vicinity of a loch or

mountain tarn; and the little herd wades round the edges and drinks of the

cool water after the glory of the summer day is over. And, when darkness

falls, the moonbeams trace their silvern paths of light across the loch

where, I suppose, the little gnomes and fays are wont to play.

Now construct in your mind’s eye the picture of a cosy

shieling house nestling quietly among the hills, where the light of a

lantern, or of a flickering candle, streams through the open doorway

across a benighted moor. No whiff of wind is breathed upon the listless

gloom of the shieling; nor is any sound heard except, perhaps, the faint

tinkling of some crystal burn, or the screech of the cailleachoidhche—’

the old woman of the night,’ as the owl is called in Gaelic—that hides

in the peat-moss close at hand.

And in the dead of night the great ships in the

Atlantic pass far beyond the shieling; and through the darkness they

whisper a word in passing...