I

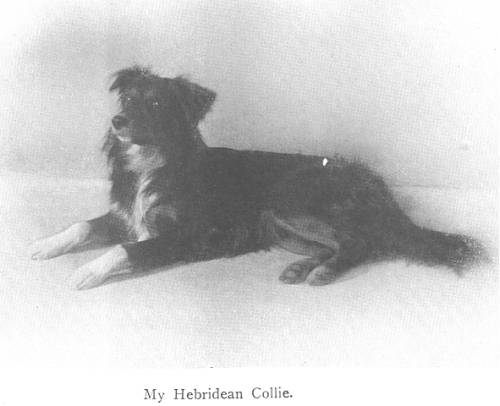

HAVE the loveliest little black-and-tan

collie. His name is Ruairaidh, or Roderic; and I brought him from the wild

Hebrides, where, as a puppy, he was wont to scamper over moor and machair,

and along the sands and wrack-covered shore at the ebbing of the tide. I

cannot adequately describe him to you, for he is far too beautiful to be

described. To enjoy him to the fullest you must really see him, and play

with him.

Although Ruairaidh is only about two years of age, he

is a splendid sailor. He and I have experienced several minor sea voyages

together; and he can stand the stormy Minch better than most human beings,

who are obliged to cross it regularly.

But the real point about Ruairaidh is that he is so

very much nicer than most of the people with whom one comes in contact. To

begin with, he is guileless and bears no malice, and is in no way subject

to moodiness. I cannot tell you how happy he is: he is by far the happiest

dog in Edinburgh, where he lives at present. And, when I see and read of

other creatures being ill-used, at least I have the consolation of knowing

that there is one dog that has never received a blow or a kick.

In the meantime it is our misfortune to be separated

from one another; and it does seem a pity that we should spend so many of

these summer days apart, when we might be roaming about together, or

paying calls. (Ruairaidh simply loves paying calls!) But they say that

absence makes the heart grow fonder; and I know that each time we meet he

pours over me all the love he has stored away in his little heart until my

return.

When I am in town, Ruairaidh and I go everywhere

together, except to church. Indeed I seldom visit where I find that he is

not welcome too; and I never give people the opportunity twice of asking

me inside, and leaving Ruairaidh sitting without on a cold, wet doorstep.

But most of my friends love him; and invitations to tea-parties are often

tendered to him in the first instance, for he is always the centre of

attraction and admiration in a drawing-room. Ruairaidh frequents all kinds

of public offices with me; and where I find it impossible to take him

inside (unless he is expressly invited), he sits motionlessly at the door

until I come out again. The point about him is that he is thoroughly

reliable, as all well-trained dogs ought to be. I know that, if I should

ask him to sit still in a certain place until my return, he will not have

moved an inch, even though I may have been absent for a couple of hours.

Ruairaidh and I have been twice in a picture-house. He

simply loves the ‘pictures,’ and becomes very enthusiastic about them,

especially when a chase or a fracas is being depicted. In fact it

sometimes requires all my strength to keep him under control when

something exciting is being shown, for he tries so hard to reach the

screen.

Both Ruairaidh and I are crazy for the water; and we

often go swimming together. When near the sea with him I have the greatest

difficulty in restraining him from rushing into it. You see, he too is a

Hebridean by birth; and the sea fascinates him, for it is in his blood. He

is also a splendid athlete. For example, he can clear an obstacle five

feet in height with the greatest ease and without turning a hair. Then we

frequently have cross-country runs together.

At the same time he is very domesticated, and will

carry brushes and brooms and other household utensils from one room to

another if requested to do so. He is also an expert carpet lifter.

We can send him for things, too, by merely naming the

objects required—e.g., a basket, boots, slippers (he knows the difference

between the latter two), a newspaper, his collar, a walking-stick, or even

bicycle clips. As a matter of fact, incredible as it may sound, he goes

regularly to the butcher’s shop, unaccompanied and carrying a basket with

a note inside it. The butcher puts in the basket what is asked for, and

places on the top Ruairaidh’s daily bone. The dog then returns with the

laden basket, holding the handle between his teeth. Then, almost every

morning he goes to the greengrocer for vegetables, and often returns with

the weekly newspapers in addition.

Ruairaidh is a bi-linguist. Of course, when in Rome we

do our best to speak as the Romans do; but to one another we endeavour to

speak Gaelic. Ruairaidh is an excellent Gaelic scholar, far better for his

age than his master is; and indeed he knows that language better than he

knows English! He was accustomed to no other tongue in Lewis; and we speak

it on every occasion when we are alone, or when we do not wish others to

understand what we are saying.

Ruairaidh has lovely glossy ears, a pair of white

spats, a sleeky black coat, and dear little brown eyes. But he has

something else—something behind those eyes. I suppose it must be his

spirit, or his soul. Whatever it is, it is that which fascinates me

most—this little personality of his. And the more I think of him, the more

I am convinced that the premises of the philosophic distinction between

reason, or intelligence, and instinct is in many respects quite erroneous.

Those who have never loved an animal can have no

earthly idea what it means to lose one.

All children should be brought up with at least one pet

about them, whether it be a dog, or a cat, or a rabbit, or even a pigeon.

I was fortunate in having had them all around me, when I was a child. Boys

and girls should be taught to respect their pets; and children who exhibit

early signs of cruelty and brutality should be swiftly dealt with.

One day Ruairaidh and I must needs part. In the natural

course of events he will leave me, and take his little personality from

me. I cannot bear to think of this parting; but, when it does come, it

will be in peace; and I shall be left with the satisfaction of knowing

that at least he understood me, and that I understood him.