Many of the victims of these persecutions, as we have

seen, took refuge in England. Let us follow them thither, and we shall

find that many of them repaid the hospitality which they received in

their exile, by rendering important services to the early reformation of

the English Church. It is not generally known how very early, and in how

many instances, and in what important posts the Scottish

reformers had an opportunity of aiding the efforts of their English

brethren in diffusing a knowledge of the Gospel among all ranks and

classes of the people of England.

The first of these numerous refugees was Alexander

Seyton, whose exile, as we before saw, commenced as early as 1530 or

1531. He lived ten years in England, during which he became a popular

occasional preacher in several of the churches of London, and was taken

into the family of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, brother-in-law of

Henry VIII., in the capacity of domestic chaplain. In 1541, his eminence

and influence as a Protestant teacher drew upon him the persecution of

Bishop Gardiner, who succeeded in inducing him to make a public

recantation of some points of his doctrine at St. Paul's Cross; and he

died in the house of his noble patron the following year.

He was succeeded in his influential post by another

Scottish refugee, John Willock; who had been a Dominican friar in the

monastery of Ayr, and was driven into exile in 1534. He, too, was a

favourite preacher in the churches of London, where he went by the name

of the Scottish friar, and was held in high esteem by the reforming

bishops and royal chaplains of Edward VI. At

one time we find him preaching to the rude soldiers of the Duke of

Suffolk in the north of England; at another time enjoying the learned

society of the doctors of Oxford. He preached by turns in the court, the

mansion, the city, and the camp. He was no doubt one of the religious

instructors of the accomplished and unfortunate Lady Jane Grey, the

daughter of the Duke. He remained in England till the accession of Mary,

when persecution obliged him to seek refuge on the Continent; where he

found a new patron in the Duchess of Friesland, to whom he recommended

himself by his skill in physic.

In the same year, 1534, were driven across the border

two other remarkable men, John McAlpin, and John McDowal, both friars,

like Seyton and Willock, of the Dominican order. McAlpin was of a

respectable highland family, and after being educated at Cologne, where

he took the degree of Bachelor of Divinity, he entered the monastery of

the Black Friars in Perth. In 1532, he rose to be prior of his house,

and soon after fell under suspicion of heresy. Having escaped into

England, he conciliated by his talents and learning the favour of

Nicholas Shaxton, the first Protestant Bishop of Salisbury, who made him

a prebendary of his cathedral, and rector of the parish of Bishopstowe

in Wiltshire. Here he laboured for some years, and was probably the

first preacher of the Reformation in that part of England. Having

married an English lady, the sister of the wife of Coverdale, his

position became one of great peril in 1540, under the severe statute of

the six articles, one of which was directed against married priests; and

he fled into Germany, where we shall meet with him again in a subsequent

part of our narrative.

John McDowal had been sub-prior of the Dominicans of

Glasgow in 1530, and was incorporated in the same year with the

university of that city—a fact which, in a friar, may be taken as a

proof of his intellectual activity and love of learning. Sharing the

exile of McAlpin, he shared also with him the friendship of the Bishop

of Salisbury, who made him his chaplain, and sent him down to Salisbury

in 1537, to preach in the pulpit of the cathedral against the supremacy

of the Pope, and in favour of the changes recently introduced by the

king. McDowal, in fact, was the first preacher of the Reformation in

that city; and he was roughly handled by all parties there for the zeal

he displayed in executing his invidious commission. Neither the king's

name nor the bishop's authority could protect him from the wrath of the

cathedral clergy and the city magistrates. He was apprehended and thrown

into prison; and several letters are still extant which he wrote from

the city-goal to Shaxton and Lord Cromwell, in which he informed them of

the hard usage which had befallen him at the hands of a people who were

still too blindly loyal to the Pope to remember their duty either to

their king or bishop. He remained in England till 1540, when he sought

refuge in Germany.

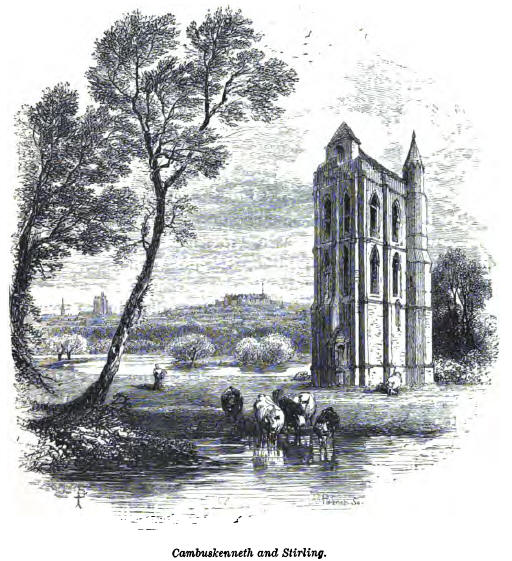

During the severe persecutions of 1539 and 1540, the

men of mark who fled from Scotland into England were numerous;

including Gavyn Logie, principal regent of St. Leonard's College, St

Andrews, and John Fife, a canon of the priory; Andrew Charters of

Dundee, a Charterhouse friar, and John Lyne, a Franciscan; Thomas

Cocklaw, John Richardson, Robert Richardson, and Robert Logie, all

canons of the Abbey of Cambuskenneth; and George Wishart of Montrose,

Florence Wilson of Elgin, and George Buchanan, tutor to the king's

sons—all distinguished for their love of classical literature and

learning. Buchanan and Wilson, or Volusenus, made no long stay in

England, but preferred to seek a refuge among the elegant scholars of

France. Of Wishart we shall have to speak in a subsequent chapter, and

of the fortunes of most of the rest we know little or nothing. But of

Robert Richardson there are still remaining three letters in the

Cromwell Correspondence, from which it appears that in 1535 and 1536 he

was employed by Lord Cromwell, who was then Vicar-General of Henry

VIII. as well as Secretary of State, as a

Protestant preacher; that he preached occasionally at St Paul's Cross;

and that he was sent down to Lincolnshire and other disturbed parts of

England to preach against the Pope's supremacy to the common people, who

were in danger of being stirred up into sedition by the agents of Aske's

rebellion.

But of all the Scottish exiles then resident in

England, the most prominent and influential was Alexander Alesius.

Having come over from Germany in 1535, upon encouragement given him by

the English agents of Henry VIII. who visited

Saxony in that year to negotiate with the evangelical princes of the

empire, he was warmly welcomed by Cranmer, to whom he brought a letter

of introduction from Melancthon, along with a copy of his celebrated

work, the "Loci Communes." By Cranmer he was introduced to Cromwell, and

by the good offices of both he was brought under the notice of the king,

to whose favour Melancthon had also recommended him. Henry was pleased

with the Wittemberg divine, made him "King's scholar," and instructed

Cromwell, who had just then been appointed Chancellor of Cambridge in

the room of Bishop Fisher, to send him down to that university as a

reader in divinity. Along with this honourable appointment, he received

a salary out of Cromwell's privy purse of twenty pounds per annum, which

was then a liberal allowance. He went into residence at Queen's College

towards the end of 1535, and commenced a series of lectures in the

public schools of the university on the Hebrew Psalter. He was probably

the first man who ever delivered lectures in Cambridge upon the original

Scriptures. But he was not suffered to continue his labours long. The

disciple of the Wittemberg Reformers was too far in advance of the

doctors of Cambridge. It soon began to be understood that he was a

Lutheran, and that it was by the recommendation of Melancthon himself

that he had obtained the favour of the king and chancellor. Heresy was

speedily detected in his teaching, and he was publicly challenged to

defend himself against that charge. He accepted the challenge, and on

the day fixed for the disputation, he awaited in the public schools the

arrival of his opponent. But the opponent failed to appear. He preferred

the safer course of plotting against him and fomenting a tumult, to the

danger of meeting so skilful a dialectician in a scholastic conflict.

Alesius was informed by his friends that his life was threatened, and

appealed to the vice-chancellor to protect him in the exercise of his

public duty. But the vice-chancellor, who was himself a Papist, declined

to interfere or to give him any guarantee. He left Alesius exposed to

the malice of his enemies. A foreigner, a Wittemberger, and the nominee

of the new chancellor, who was unpopular in Cambridge (for the

university was still lamenting the fall of Fisher the position of the

king's reader in divinity was one of great peril; and in the present

temper of the university, which was disgusted with the king's new

ecclesiastical policy, he had but a poor prospect of official

usefulness, even if he might have been sure of his personal safety. He

was compelled to yield to the necessity of the time, and to return to

London after less than a year's residence in the university.

As he still continued, however, in the service of

Cromwell, his powerful patron had soon another opportunity of employing

his remarkable learning and talents. In 1536 or 1537, there was a

convocation or conference of the bishops assembled at Westminster to

discuss some theological questions, which had been submitted to them by

the king. Cromwell, as vicar-general, presided in the conference and

managed the debates. On his way, one day, to the place of meeting, he

chanced to fall in with Alesius in the street, and invited him to

accompany him and take part in the discussion. The question in dispute

happened to be the number of the sacraments ; and after a prologue by

Cromwell, who sat at the head of the table, the debate began with an

address from Cranmer, the archbishop, who recommended to the bishops a

close adherence in the discussion to the Word of God, as the only

authentative standard in religious controversies. But it was only a few

of the bishops who were of Cranmer's mind : John Stokesley, Bishop of

London, followed on the opposite side, and contended for the seven

sacraments of Rome, on the joint authority of Scripture and tradition.

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford, spoke next, and animadverted severely

upon the reasonings of Stokesley, as a relapse to the old scholastic

method of arguing such questions, which both the king and his

vicar-general had counselled them to abstain from upon that occasion. It

was at this point of the debate that Cromwell brought in the assistance

of Alesius. He introduced him honourably to the assembly, as a man of

piety and learning ; and Alesius proceeded, with equal modesty and

ability, to deliver his opinion. The validity of a sacrament, he urged,

depended upon the promise of God's grace being attached to it: the

promise of God's grace could only be found in God's own word; the

authority of the Scriptures was the only true and infallible standard of

faith, and tried by that authority, the seven sacraments of Rome could

not be sustained. Before Alesius had finished his argument, the hour of

adjournment had arrived, and Cromwell requested him to stop, promising

that he should be heard again on the following day. But Stokesley and

the other popish bishops, smarting under the strokes of his logic,

remonstrated so warmly with Cranmer against the irregularity of bringing

in a stranger and foreigner to take part in their debates, that the

archbishop was obliged to make a representation to Cromwell upon the

subject; and the latter, not caring to increase the irritation of the

popish party by pressing the point, contented himself with requesting

Alesius to commit his whole argument to writing, and undertook to bring

it in that form under the notice of the bishops. This argument the

author afterwards published in Latin, with a dedication to John

Frederick, Elector of Saxony; and the work was so much esteemed by the

English Protestant divines, as a demonstration of the sole authority of

the Word of God in matters of faith, that it was translated into English

by one of them for popular use.

Alesius employed himself in London for several years

in the practice of medicine, which he had probably studied at Wittemburg;

but having married during these years, the statute of the six articles

compelled him, in 1540, to consult his safety, and that of his family,

by a hurried retreat to the Continent He left at the same time, and

probably in company, with his countrymen, John McAlpin and John Fyfe,

and all three experienced a warm and hospitable welcome from Alesius's

old friends at Wittemberg.

Thus early in the history of the Reformation began a

series of reciprocal good offices between the two British kingdoms,

which continued for many subsequent years, and which ended in

consolidating and securing the foundations of the Reformed Church in

both parts of the Island.