|

IN 1884, I was appointed by

the Free Church of Scotland to work as a medical missionary amongst Jews and

others around the Sea of Galilee. My first months were spent with Dr. Vartan

of Nazareth. He had been in the country since about 1860, and being the

only medical man in Northern Palestine, he had often been called to minister

to the sick in Tiberias. His services were gratefully appreciated; and it

was through his influence that I was able to rent a house from one of the

chief rabbis, and so to establish myself as the first resident missionary at

the Sea of Galilee.

I had been well warned

regarding the unhealthiness of the place, [The deaths that have taken place

in the mission circle have not been due to any special condition of Tiberias.

Apart from the intense heat in summer, Tiberias is as healthy as most

Eastern towns, and quite bearable by Europeans. except during the three or

four hottest months.—D. W. T.] and the fanatical nature of the inhabitants,

Jewish and

Moslem; but the needs of the

place appealed to me in a way that I could not resist. Crowds soon came and

besought me to heal them and their sick friends; but when they understood

that I was a Christian missionary, and commended to them Jesus of Nazareth

as the Messiah and as the Lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the

world, their indignation was roused, and they determined to rid their holy

town of this deceiver of the people." The rabbi who had let me the house was

denounced in the Hebrew newspapers, and he tried to get me to leave. Once

when very ill I was taken by night by Dr. Vartan to Nazareth. I soon

recovered, but a report that I had died was spread in Tiberias by some of

the Jews, evidencing what they hoped or anticipated. "Cherems " or bans of

excommunication from the synagogue on any who, whether sick or not, visited

the missionary were publicly proclaimed from the various synagogues. The "haluka,"

or alms from Europe, etc., would not be distributed amongst any who

disobeyed the order of the rabbis ; and so for a time the mission was

boycotted by the Jews.

There were, however, Moslems

and a few Greek Catholic Christians in Tiberias who continued attending the

dispensary, and in many cases they were greatly benefited. So some sick

Jews, and especially some Jewesses with sick children, braked the bans of

the rabbis, and sought the aid of the Christian doctor. Now was the critical

time; but the devotion of the mothers to their children proved strongest,

and the bans began gradually to be forgotten, though now and then there

would be a fresh outburst of opposition. Very gradually the opposition was

overcome, and on passing through the streets grateful patients would take

off their hats, children would run to kiss the doctor's hand, and many would

entreat him to step aside and see their sick ones.

One of the Jewish rabbis had

been specially bitter and stubborn in his opposition, but it was removed in

the following way. His daughter-in-law got somewhat disturbed in mind, and

she was taken to the great synagogue of Rabbi Meir, near the warns baths of

Tiberias. There she was kept within the iron railing around the tomb of the

late `yonder-working rabbi, that his good spirit might drive out the evil

spirit that was in her. Her husband grew tired of this procedure, as there

were no signs of improvement, and he sought my advice. Rational treatment

restored the poor woman to a sound mind.

Some time later the rabbi

himself fell ill with an inflamed sore throat. He would not deign to send

for me; but one morning, when he was almost suffocating, his son (whose wife

had formerly been my patient) rushed into my house, and frantically besought

me to come to his father. I was able to give him immediate relief, for which

he has never ceased to be grateful, and, as far as I know, he has never

since opposed the medical mission.

Great difficulty and

discomfort were experienced in working in native hired houses. Tiberias,

from its low position (682 feet below sea-level), is excessively hot, and

has the reputation of being the scat of the "king of the fleas!" Most

probably every Eastern town has such a king of its own. Unfortunately there

were other discomforts than vermin of various kinds and occasional snakes.

Worst of all, perhaps, were the insanitary odours all around.

The only suitable site for

mission buildings was to the north of the town, adjoining the boundary wall.

It was owned by the mufti, the religious head of the Moslems. We had coveted

it from the first time we visited Tiberias; but to have asked for it would

probably have been to lose it, considering the opposition of the government

to all foreigners, and especially to missionaries. After waiting a few

years, the owner, becoming a friend, offered to sell it, and we bought it

for £60. Very great difficulty was experienced in obtaining title-deeds,,

and before receiving them an understanding had to be signed that there would

not be erected on the ground either a hospital, school, or church without

express permission from. the Sublime Porte. Again, when receiving local

permission to erect the two dwelling-houses that now adorn the plot, another

undertaking had to be signed that they would not be converted into either

churches, schools, or hospitals, or any other building for which sanction is

previously required from Constantinople. In 1890, the first mission house

was occupied by the Rev. William Ewing, who in 1888 joined me as clerical

colleague, the second or medical missionary's house being occupied in 1892.

Meanwhile, a kind of hospital

work was being carried on in a native house, where serious cases, especially

those requiring operative treatment, were attended to. It began in this way:

I had already frequently performed operations, and allowed the patients to

sleep on the floor in the waiting-room, so as to be under my constant

supervision. One day there was brought to the waiting-room a poor Moslem

woman from a distant village, who was suffering from a diseased bone in her

leg. The smell was so offensive that she was obliged by the other patients

to wait in the court outside. The painful part had been cauterized by native

practitioners, and was now gangrenous. I informed her that it would need

daily attention for a long ` time and advised her to get a lodging in town,

where I would visit her. An hour or two after, the poor woman returned

exhausted, carried on the back of her mother, and begged to be allowed to

lie and die at peace under a low archway in the dispensary court. She had

sought in vain for a lodging. Even in the khans, or stables, she was not

allowed to remain, on account of the smell from her leg. I sent my Jewish

servant, who was full of sympathy for her, to try to hire a whole room, in

which I might place her. We got one from the chief rabbi, who had been my

patient; and here, after an operation, the poor woman was tended till she

made a good recovery, and left with feelings of gratitude in her heart that

no words could express.

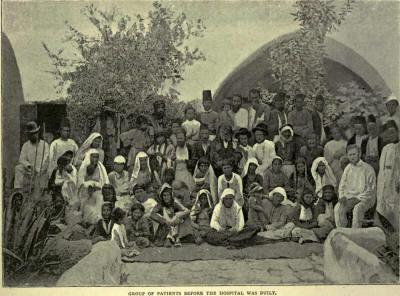

In this room (about sixteen

feet square, which by an upright and a horizontal partition was divided into

three apartments, and hired for ten francs a month), with one Jewish woman

as nurse, cook, cleaner, etc., we had our first hospital, containing

sometimes as many as eight patients. (A group of some of these patients may

be seen in the accompanying picture.) Jews as well as Moslems were treated

here; but several required operations that could not be undertaken unless in

proper premises, with skilled nursing. Hence I applied to the local governor

for advice as to how to procure a firman or permit from the Sublime Porte to

erect a proper hospital. He was afraid to have anything to do with the

matter, and advised me to apply directly to Constantinople. I visited

Constantinople. The application was sent in through the British Embassy, and

the petition, some months afterwards, was submitted to the local authorities

at Tiberias for their verdict. A new local governor was then in Tiberias;

but,

fortunately for us, he and

several of his predecessors and associates who had been ailing were indebted

to us for medical aid. Some native gentlemen, one especially, used their

influence with the court, and a favourable reply was returned. The firman

was granted, to the astonishment of all who knew the usual delays and

difficulties encountered in such matters.

As originally planned, the

hospital was to be built on part of the first plot of ground bought. On that

site a large sum of money would be required to raise the foundations to the

level of the road, but there seemed no alternative. An adjoining piece of

land was much more suitable; but there seemed no hope of obtaining it, as it

was public ground, and often used by travellers for camping. In God's

providence, a high military official, the agent for the Sultan's private

property in the district, visited Tiberias, and saw our dwelling-houses so

nice and clean and airy. He expressed a desire to build one for himself

something like them, and asked if he could have the adjoining piece of

ground. It was at once given to him, with the best title-deeds, at a merely

nominal sum. While residing in Tiberias he had several tinges been our

patient, and was very friendly. Later on, at a most opportune* moment,

whether frightened by the extreme heat of summer, or for other reasons, he

gave up the idea of building or living in Tiberias, and offered the ground

to us for one hundred Turkish pounds. The title-deeds iii our naive were

placed in our hands several days before we were able to collect the money

for payment.

The original plans of the

hospital were modified to suit the new site in time to be sent to

Constantinople and embodied in the firrnan afterwards issued. Not only had

we thus obtained a better site, but the cost of the site was far more than

covered by the saving in the foundations in the new site, as the rock was on

the surface, and much material was obtained from a quarry which was opened

within the ground.

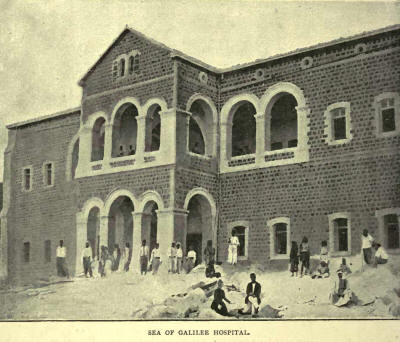

In the spring of 1893, the

ceremony of digging the first sod (or rather, of excavating the first

basketful of earth) for the foundations of the hospital was performed by

John R. Miller, Esq., of Glasgow, a member of the Jewish Committee, and an

intimate friend of the late Dr. Andrew Bonar, so much associated with' the

beginning of this mission. The governor, who was present, read aloud the

firinan sanctioning the building in the hearing of the large crowd gathered

around. The hospital was erected without a hitch or interruption, in a

remarkably short tinge, and by native workmen superintended by Germans. By

the end of 1893, the building was finished.

Thus was erected the first

hospital that has ever stood on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. Built with

such manifest tokens of God's overruling providence, surely He looks down

Upon the undertaking with approbation, and will bless the efforts of His

servants who, striving to walk after the example of their divine Master,

"heal the sick, and say, The kingdom of God is come nigh unto you."

The hospital has

accommodation for twenty-four beds and six cots. Each bed is named after its

supporter.

Attached to the hospital

there is an outdoor or dispensary department, where, on an average, between

forty and fifty patients are attended to daily; but sometimes as many as one

hundred seek advice in one day. A lady, in memory of her sister, has given

£100 for the erection of a room to be used as a shelter for outdoor patients

who come from a distance and require to remain overnight.

The heat in Tiberias during

summer being excessive, trie hospital will be closed during the hottest

months; but it is hoped that the dispensary department will be kept open all

the year round, with the help of a native medical assistant.

In summer the missionaries

work in Safed, which is over three thousand feet above the lake, where there

is a branch station, with boys' and girls' schools, and a medical mission

under a native assistant, who is a graduate in medicine of the American

Mission College at Beyrout and of Constantinople. Here there is a very large

dispensary practice, especially in summer, the population being more than

four times that of Tiberias.

Our time is chiefly taken up

in attending to those who come to the medical mission ; but there are many

very ill in their homes in the town and in the villages and Arab encampments

around the lake who cannot come to us. If they are to be reached at all, we

must go to them.

The Jewish and Moslem homes

are now all open to us for medical and friendly visits, and when religious

topics are introduced, as a rule they are listened to with patience and

interest.

In the homes of the Jews, and

even in their synagogues, which are the only homes many •poor Jews have, we

have expounded from Moses and the prophets the scriptures concerning Christ

as fulfilled in the New Testament, and pressed Him on them for acceptance;

but it is almost impossible in the present state of affairs for a Jew to

confess Christ openly, unless he is willing to face persecution of the most

bitter kind, to leave his kith and kin, and to run the risk of starvation

and even death.

On one occasion I was called

to see a poor woman at the Moslem village of Fik (Aphek), on the uplands on

the other side of the lake. She had previously benefited by treatment at

Tiberias, but had had a relapse, and was unable to travel. I arrived late.

After partaking of the ordinary family supper of a mess of pottage, I spent

an hour or two telling the men and women of the "Good Physician," who used

to walk around the lake lying just below them, but of whom they knew

nothing. At last, quite exhausted, I begged to be allowed to sleep. A

mattress, pillow, and quilt were spread for me on the floor just where I

sat, at the side of a wooden fire, the smoke from which had to escape as

best it could from the unglazed window and broken door. I tried to sleep,

but it was impossible. The men who were in the room were snoring, and the

sheep were quietly chewing their cud, but the poor woman I had specially

come to see whiled away the time by talking to the women who were "sitting

up " with her.

"Did you hear how he spoke?"

she said. "That's how he speaks to the people over in Tiberias. He speaks to

the women as if they were men, and they don't regard it a. sin to eat such

and such things."

She tried to repeat some of

the ideas she had gathered at the medical mission and at the girls' school,

which she had also visited. She repeated the text, "God be merciful to me a

sinner," and showed she had got a grip of what sin, mercy, and a Saviour

were. My eyes were filled with tears of joy and gratitude to God that He was

apparently blessing our work, and that His word was not returning unto Him

void. On a subsequent occasion I visited some Moslem villages and Arab

encampments farther east, and was everywhere well received. One grateful

patient, Sheik Hamad, sent and shifted my camp to his village, where he

entertained me with his best. He had come to Tiberias with a diseased leg,

fearing that it would never be of any use to him ; but he returned home, not

only with a useful leg, but with a Bible which he could read, and a hunger

after the truth as it is in Christ Jesus.

At our camp we found him

still eager to learn more. He took us to the mosque, that we might exhibit

the magic-lantern to the people; but although he seemed greatly looked up to

by the people as one of the chiefs, we deemed it more prudent to have the

meeting in the large guest-room of time place. When the meeting was closed,

Sheik Hamad said that I had missed out certain portions of the life of

Joseph, which I had exhibited. This was an evidence to me that he had been

reading his Bible, which I had marked at several places, and I told him he

must tell the people the whole story. I learned that he had often read from

his Bible to a crowd of astonished hearers. He is not far from the kingdom,

but humanly speaking, it would be impossible for him to profess Christianity

and live in the land. He would likely get, unawares, a cup of coffee with a

little arsenic in it, and die what would be called a "natural death."

Our medical mission is

opening the door for the gospel among both Jews and Moslems. |