|

The sacred yew

in Fortingall, central Scotland, reputedly the oldest tree in Europe

by Barry Dunford

The Fortingall Yew tree

© Copyright Barry Dunford

Located close to the

geographical centre of Celtic Scotland is to be found a remarkable yew

tree which is currently believed to be around 5,000 years of age, thus

dating its origins to about 3,000 B.C. This yew is to be found in

Fortingall, Perthshire, which lies at the entrance or portal to Glen

Lyon, the longest and arguably the most spectacular glen in Scotland.

When the 18th century traveller and naturalist Thomas Pennant (1726 -

1798) visited Fortingall, he reported that the girth of this age old yew

was fifty six and a half feet. One can but wonder what is giving life

force to this extraordinary aged yew tree which can still be seen to be

thriving at the present time, and from whence came the mother yew which

gave birth to this archaic tree sited at Fortingall?

In a land which is

permeated with an ancient Celtic mythos relating to fairy realms and

other worldly devic entities, such an elderly yew tree would have been

highly venerated during the remote ages of past antiquity. Indeed, it

has been said that Beltane fires celebrating the old Mayday festival

were at one time lit at this site. Moreover, this ancient yew may have

been 3,000 years old when, according to a local oral tradition, Pontius

Pilate was born at Fortingall, which translates from the gaelic

placename 'Feart-nan-Gall' as the 'Stronghold of the Strangers'. Nowhere

else in Scotland, or for that matter in the British Isles, has an oral

tradition and association with the birth of Pontius Pilate; so why

should the tiny and obscure hamlet of Fortingall lay claim to this

tradition, unless there is an intrinsic element of truth in what would

otherwise be deemed as an audacious presupposition.

The yew is a primordial

tree and it is believed to date back for at least two hundred million

years, which considerably antedates the era of the human race. It is no

wonder that from time immemorial the eternal yew appears to have been

seen as the immortal tree of life and held with sacred reverence

throuthout the ages. According to ancient lore it would appear that the

yew was seen as an arcane repository, i.e. a tree of knowledge. It has

also been noted that yew trees were often associated with ancient hill

forts and, true to form, on an elevated position close by the Fortingall

Yew is to be found the remains of an old hill fort called Dun Geal which

translates from the gaelic as 'the white fort'. At the time of Christ,

Dun Geal was the residence of the Caledonian King, Metallanus, of whom

local tradition claims Pontius Pilate was a relative.

Commenting on the

Fortingall Yew, Vaughan Cornish, D.Sc., in his book The Churchyard

Yew & Immortality (1946) remarks: "Of Yew trees in the churchyards

of Scotland the most celebrated is that of Fortingall in Perthshire. The

tree as measured in A.D. 1771 by Thomas Pennant was 56 1/2 feet in

circumference and as measured by Daines Barrington in A.D. 1769, 52

feet, thus being greater than that of any churchyard Yew of England or

Wales. This led to the supposition that of all the trees in Britain the

Fortingall Yew was monarch of antiquity. Upon this belief legends grew.

One of these was embodied in a poem by W. Cowan, from which the

following is a quotation:

'Here Druid priests their

altars placed,

And sun and moon adored.

* * * * * * *

A tree - the sacred Yew,

Symbol of immortality -

Beside their altar grew.'

Another legend is of

special interest because it links the Yew with the life of Christ, as

the Thorn of Glastonbury is linked by the legend of Joseph of Arimathea.

Near Fortingall are the remains of a Roman station, where the tradition

is that the father of Pontius Pilate was a Roman legionary, and that

here his son was born, and that the child played under the Yew, which

was already of venerable age."

Aerial photographs of

Fortingall reveal a marking in the landscape which is believed to

indicate the enclosure of an early Christian monastic site.

Interestingly, this monastic settlement appears to have been centered

around the Fortingall Yew tree. Such is the reputation of this

remarkable Yew that in 1993 a sapling from this archaic tree was planted

in Glastonbury Abbey, while concurrently monks from the Tibetan Buddhist

monastery, Samye Ling in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, planted another

sapling on Holy Island, off the coast of Arran, Scotland. More recently

cuttings were taken from the Fortingall Yew to be grown by the Forestry

Commission at Roslin, another historical sacred site in Scotland. These

yew cuttings will eventually be planted around the country at such

places as the arboretum at Scone Palace. Interestingly, Scone was at one

time home to the famous "Stone of Destiny" which was central to the

Coronation ceremony of the old Scottish Kings.

There has been a

traditional association with the mythos of the sacred yew and the

natural philosophy of the Celtic Druid Magi. "Without doubt the yew

stood for sacred mystery in the Druid tradition; yews were planted

systematically about the places, often wells, that held sacred truths,

perhaps to awe votaries as much as because the trees themselves held

sacred properties....In Druid tree language it stood for the Ovate

grade, one who specialized in learning concerning the mysteries." (The

Book of Druidry by Ross Nichols, 1990). In both the Druidic

tradition of reincarnation, and the later Christian doctrine of the

resurrection, the yew was viewed as a natural emblem of everlasting

life.

The 19th century

antiquary, Godfrey Higgins, in his erudite work, The Celtic Druids,

published in 1829, makes the following intriguing observation: "Perhaps

it may be thought far fetched, but, may not the name of the Yew, the

very name of the God Jehovah, have been given it from its supposed

almost eternity of life? It is generally believed to be the longest

lived tree in the world. If this were the case, when a person spoke of

the Yew-tree, it would be nearly the same as to say the Lord's tree."

Moreover, in the Himalayas the yew was sometimes called deodar which

means 'God's Tree'. There has even been a revelatory comment made that

"the Yew is as pure a manifestation of divine consciousness in our

midst, as the presence of a Buddha or Christ is!" (The Tree of

Immortality, The-Tree.org.uk)

There is a tradition that

the Cross of Christ was a yew tree probably because of its symbolism of

immortality. This may explain the following observation: "Although the

Yew was planted on temple sites, and was a survival of cultus

arborum (tree worship) yet, strange to say, it was never damaged,

but was adopted by the Christians as a holy symbol." (The Church Yew

& Immortality by Vaughan Cornish). Furthermore, the yew also figures

in the folklore of the gypsies who believe that the planting of a yew

near one's home provides protection. Interestingly, about a century ago

gypsies were found to be living in the hollow churchyard yew at Leeds in

the english county of Kent.

Legend claims that the

Fortingall Yew marks the actual geographic centre of Scotland and its

heart or 'axis mundi', although it is possible that geographically the

real axis mundi is located on Mt. Schiehallion ("the fairy hill of the

Caledonians"), the holy mountain which lies just five miles north of

Fortingall. However, there may be a connective node between this sacred

yew and the holy mountain to the north of it. In his insightful work

At the Centre of the World (1994), John Michell observes: "Every

Celtic community, tribe and national federation of tribes had its sacred

assembly place of law of justice. These were centrally placed at the

mid-point of their territories....the first thing that was needed by

those who created sacred landscapes was to locate the country's main

axis, the preferably north-south line between its two extremities,

passing through the centre. It corresponded to the world-tree, the

shaman's pole by which he ascends to the world of spirits, and all other

symbols of the universal axis....Guarding and overlooking the omphalos,

generally to the north of it in the direction from which disruptive

forces are traditionally supposed to emanate, is found a lone, conical

mountain. Its mythological prototype is the mountain at the centre of

the world. The chief god of the pantheon resides there, presiding

awesomly over the rituals in his sanctuary below." It is interesting to

note that the geographical relationship between the conical Mt.

Schiehallion and the Fortingall Yew tree correlates exactly to this

ancient mythos as described by John Michell.

Mount Schiehallion ("The

fairy hill of the Caledonians")

Following on from this,

Geoffrey Ashe in his work The Ancient Secret (1979) relates that

the shaman climbs a pole or tree into the celestial realms: "The main

feature of the shaman's universe is the cosmic centre, a bond or axis

connecting earth, heaven and hell. It is often pictured as a tree or a

pole holding up the sky. In a trance state, a shaman can travel

disembodied from one region to another, climbing the tree into the

heavens or following its downward extension. By doing so he can meet and

consult the gods." Commenting on this observation, Dr. Gordon Strachan

says: "The pole, axis or tree is in fact the axle of the cosmos which we

encountered in our discussion about the holy mountains such as Meru,

Olympus, Alborg and Aralu, of which Mount Zion and indeed Mount Sinai

were also examples. These, we established, were linked to a prototype in

the north which may well have been connected with Stonehenge or other

megalithic sites, but which was ultimately identifiable as the celestial

North Pole. This now appears to be the same pole, or axis mundi

up which the shaman climbed or rather flew in his astral body, to the

council of the gods....the implication is that Ezekiel, Daniel, Enoch

and Moses on Sinai, not only had shamanic, out-of-body experiences of

the ascent to the divine presence, but also that this was via the

axis mundi up to the celestial pole, past the phantasmagoria of the

northern lights and through the hole in the apex of the vault of heaven

which St. John in Revelation calls an 'open door'. (Rev. 4:1)". (Jesus

the Master Builder: Druid Mysteries and the Dawn of Christianity,

1998).

In this same work Gordon

Strachan goes on to say: "The unmistakable implication is also that

Jesus was himself the supreme initiate of this experience." In the light

of the foregoing one might speculate as to whether Jesus visited the

Fortingall Yew during his "lost years" which have gone unrecorded in the

Canonical Gospels. Other research by this writer suggests that Jesus may

indeed have visited ancient Alban, i.e. the Scottish Highlands and

Islands.

It has been noted that

"Yew were also often planted at the centre of a tribal territory, which

often served as a gathering place for clan meetings. The Fortingall Yew

is one such example." (The Tree of Immortality, The-Tree.org.uk).

Furthermore, John Michell comments: "The powers of ancient kings,

chiefs, priests and law-givers were not of human origin but were derived

and borrowed from the symbolic centre. This was also regarded as the

birthplace of the tribe, so it belonged to the people as a whole rather

than to any ruler they might elect. Once chosen, the king was irradiated

with the mystical power of the centre and became the agent and

interpreter of its influence. Installed upon the local world-centre

rock, at the point of mediation between the law of heaven and the will

of the people, he surveyed the cosmologically ordered divisions of his

realm. Its ritual boundaries, defining the spiritual, astrological

limits of each section, may have been marked by the straight alignments

of stone pillars which converge upon Boscawen-un and other stone

circles." (At the Centre of the World)

It is known that the yew

was often used as a landmark. Writing about straight tracks or ley lines

on the landscape, Alfred Watkins in his classic work The Old Straight

Track (1925) makes an interesting observation: "There is every

reason to surmise that trees were planted in prehistoric times as

sighting marks....trees are joined with stones, water [wells],

mountain-tops, mounds, and fire as objects of ancient reverence and even

worship; all these are found as sighting points on the ley." Notably, a

number of telluric ley lines or earth energy currents have been dowsed

as passing through Fortingall, thus indicating that a major earth energy

vortex may be located here. Could this be another factor in accounting

for the specific placement and perhaps longevity of what is reputed to

be the oldest tree in Europe?

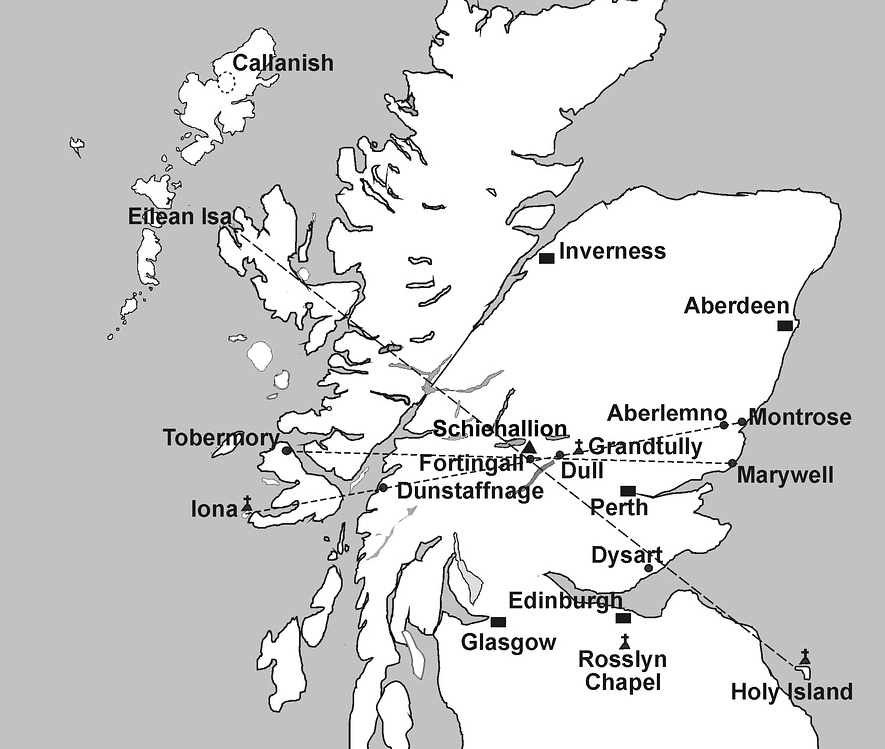

Map of Scotland showing three ley

lines and some of the ancient sites

which they traverse. 1. Between the Holy Isle of Iona and Montrose

(Mount

of the Rose); 2. Between Tobermory (Well of Mary) and Marywell; 3.

Between Eilean Isa (Island of Jesus) and Holy Island (Lindisfarne). Note

that all three leylines intersect at the central nodal point of

Fortingall.

© copyright Barry Dunford, extracted from "The

Holy Land of Scotland"

Finally, to quote Sir

George Trevelyan: "What magic is there in the ancient yew trees! What is

it in them that fires our vision and fills the soul with mystery,

touching ageless history? We associate our yew trees with our

churchyards....The great yew trees can be 2,000 years old, or 3,000, or,

in some cases, they may reach 4,000 years or more, and our churches were

mostly built less than 1,000 years ago. The yews came first, planted on

sacred sites known to the Druids. The later church builders were

sensitive to the holy places and knew where to build their churches. So

let us awaken to the wonder of the yews, planted long before the

churches were built, and linked with ancient pre-Christian ritual and

mystery." (The Sacred Yew by Anand Chetan and Diana Brueton,

1994).

The writer with

Sir George Trevelyan at the Fortingall Yew in May 1994.

Six months earlier,

Sir George planted a sapling from this yew tree in Glastonbury Abbey

, England. At the

same time monks from the Tibetan Buddhist monastery, Samye Ling,

Scotland, planted another sapling from this same yew, on Holy Island off

the coast of Arran, Scotland.

© copyright Barry Dunford

© Copyright 2004 Barry

Dunford. All rights reserved. PERMISSION FOR

USE: No part of this article may be published without the

permission of the author Barry Dunford |