|

IN the beginning of the present century the

enthusiastic coterie of artists, mostly emanating from the Trustees'

Academy and the class of Alexander Nasmyth, felt themselves strong

enough to venture on a public exhibition of their works in r8o8, under

the title of the Society of Incorporated Artists.' This was the first of

the kind held in Scotland of any pretence, if we except the open- air

one held in connection with the Academy of the brothers Foulis of

Glasgow. Previous to this time several Scottish artists, as we have

seen, had exhibited at the Academy in London, notably Gavin Hamilton,

Ramsay, More, and Runciman. An attempt is mentioned as having been made

in 1791—Alexander Nasmyth renewed the effort three years later, and a

third unsuccessful attempt was made in 1797—to form an Academy with

exhibitions in Edinburgh. Although not of any high degree of excellence

compared with the later exhibitions of the Scottish Academy, that of

i8o8 did incalculable good in exciting the attention of the public, and

also in affording the artists an opportunity of showing their

productions. There being at that time very little demand for anything in

the way of pictures, except in the line of portraiture, that branch of

the art was the most strongly represented, chiefly by the works of

George Watson the president, miniatures by W. Douglas, and chalk and

medallion heads by John Henning. Carse exhibited a Tent-Preaching, a

Brawl in an Alehouse, and the Chapman; and W. Lizars, the Earl of Buchan

crowning Master Gattie. In the line of landscape, the most important

works were by Alexander Nasmyth, consisting of Stirling Castle,

Glenshira, and Windermere; Inveraray Park, by Patrick Nasmyth; and chalk

drawings by Thomson of Duddingstdn. Some flower pictures by Syrne were

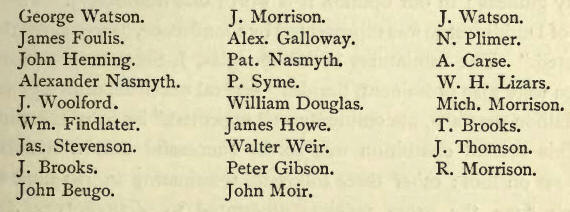

also favourably noticed. The following is a list of the artists

contributing to this exhibition

The

second exhibition was opened on the 20th May 1809, and during the six

weeks the pictures were on view, nearly 500 guineas were collected at

the door. Forty-eight artists contributed works, and in point of

excellence and variety this exhibition was greatly in advance of the

previous year's. It was reviewed in the 'Scots Magazine' and the

'Edinburgh Star,' and this gave rise to the publication of a half-crown

pamphlet, 'Strictures on the Remarks,' written in the usual complaining

style of overlooked artists. To this exhibition Raeburn, who had then

achieved his reputation, contributed five portraits, including a full-

length of Mr Harley Drummond on horseback, and a portrait of a gentleman

(Mr Walter Scott)—"An admirable painting with most appropriate scenery."

This was the well-known portrait of the Wizard of the North with his dog

Maida. Among the other portraits favourably criticised were George

Watson's portrait of an old Scotch Jacobite, and Geddes's portrait of

Mrs Eckford. J. Watson was represented by Lord Lindsay and Queen Mary;

W. Lizars, by Jacob blessing Joseph's Children; Carse, by the Wooer's

Visit ("A wonderful picture, somewhat in the manner of Wilkie, our Scots

Teniers "), and a Country Fair; A. Fraser, by a Green-Stall; and Howe,

by a Barber's Shop,—" A very spirited picture, with much character and

considerable humour," which praise, however, the critic qualifies by

noticing an absence of it and finishing, a matter of acquirement." 1 In

landscape the veteran Alexander Nasmyth was absent; but Patrick showed a

View in Westmoreland (concerning which a critic says, "We have been

informed that this picture has been disposed of for thirty guineas; in

our opinion it is worth one hundred"). Thomson of Duddingston was

represented bya landscape," most agreeably painted." The miniatures by

W. Douglas, J. Steel, and S. Lawrence were also prominent, besides

"several excellent drawings and medallion portraits, uncommonly well

executed," by John Henning.

This second

exhibition was so far successful that a life-class was set on foot;

other three followed, terminating in 1813, up till which time the gross

receipts amounted to £2828, xs. 6d., leaving a clear profit of £1633,

8s. 6d. on the whole series of five. Concerning these exhibitions Lord

Cockburn in his 'Memorials' states, that owing to the want of

appreciation on the part of the public they were not a financial

success, and that the artists soon found that the money charged for

admission to their exhibitions could not be depended on to pay for their

expenditure, when most unlooked-for aid released them of this

difficulty. "A humble citizen," he adds, "called Core, who kept a

stoneware shop in Nicolson Street, without communicating with any one,

hastily built or hired—I rather think built—a place, afterwards called

the Lyceum, behind the houses on the east side of Nicolson Street, and

gave the use of it to the astonished artists." It was probably due to

the generosity of this individual that the exhibitors were in possession

of this sum of money; but unfortunately, the constitution of the Society

had not been sufficiently binding to secure its permanency, and its

success was the cause of its ruin. By a most unfortunate resolution

passed by a majority of the artists, it was determined to divide the

money among the members of the Society; and thus, by the greed of a few

selfish, and mostly unknown individuals, art in Scotland was thrown at

least twenty years backward. After the meeting at which the resolution

was carried, efforts were made to have it annulled, chiefly by the

president George Watson, Alexander Nasmyth, J. Foulis, J. Beugo, Henry

Raeburn, A. Galloway, and John Henning, but without effect. Had the

efforts of these gentlemen been successful, the Society of Incorporated

Artists might now have been one of the richest and most influential

public bodies in Scotland, and the later contentions between the Royal

Institution and the Scottish Academy would never have occurred. In the

exhibition of 1808, 178 works were exhibited by the twenty-six artists

named, thirteen of whom formed the Associated body; and in 1813, when

the Association was dissolved under the presidency of Raeburn, elected

the previous year, 209 works were exhibited by sixty-eight artists, only

twenty-five of whom were members, who thus received about £65 each.

Three more annual exhibitions followed in Raeburn's rooms in York Place,

after which they were discontinued, although several attempts were made

to carry them on, chiefly by individual artists.

The retarding influence exercised on the

development of art in Scotland by the removal of the Court to London by

James VI., had been repeated afterwards when the union of the two

kingdoms was effected. From that time Edinburgh had ceased to be the

headquarters of the Scottish nobility, who had all but entirely

abandoned it as a place of residence. Scott mentions that he never knew

above two or three of the peerage to have houses there at the same time,

and that these were usually among the poorest and most insignificant of

their class. The wealthier gentry had followed their example, very few

of whom ever spent any considerable portion of the year in Edinburgh,

except for the purpose of educating their children, or superintending

the progress of a lawsuit; and there were not likely more than a score

or two of comatose and lethargic old Indians to make head against the

established influences of academical and forensic celebrity.' Thus,

whatever efforts were being made at the time of winding up the Society

of Incorporated Artists in 1813, nothing tempted painters into any other

line than that of portraiture. Young William Allan, after having gone to

London to study, was roving through Russia while that country was in the

throes of the French invasion. Wilkie had just burst into fame in

London, where commissions from the nobility were pouring in upon him.

John Burnet had followed his old fellow-student, and when only

twenty-five years of age, was teaching the English engravers the wisdom

of reverting to an earlier and better manner. Geddes, after four years'

experience of Edinburgh, had returned to London and was then setting out

for the Continent. David Roberts was struggling for bare life, either

travelling with a caravan of strolling players, sometimes taking a part

in the performances, or painting scenes for stationary theatres at

twenty-five or thirty shillings a-week. Horatio MacCulloch was just

leaving school at the early age in which Scottish boys were put to work,

and probably flattening his nose against the print-shop windows of

Glasgow, with as unhopeful a future as could well be. Macnee, Duncan,

Dyce, Harvey, and David Scott, all of whom were about the same age, and

so eminent in their after-lives, were dividing their attention between

arithmetical sums, school-slate drawings, and stories of Wallace and

Bruce. Francis Grant, the future president of the Royal Academy, was in

his classics, and John Phillip was not yet born.

Lord Cockburn has remarked that the eighteenth was

the final Scottish century, and that most of what had gone before was

turbulent and political, and all that has come after has been English.'

The manners and customs of the people were undergoing a change, and an

appreciation of art was beginning to manifest itself among the public.

Pictures were more looked at; architecture was claiming and receiving a

large amount of attention; the appearance of streets and dwelling-houses

was a matter of consideration; and a good class of illustrated

literature, in which local scenery formed a large portion, began to be

issued from the press. The author of 'Peter's Letters' gives an

interesting sketch of a curious Edinburgh character and his shop in the

High Street, a year or two later, which throws some light on the

position of art there. The shop was a clothier's, occupied by a father

and son, both named David Bridges, and was one of the great morning

lounges for old-fashioned cits, "where they conned over the Edinburgh

papers of the day or discussed the great question of burgh reform. The

cause and centre of the attraction lodged in the person of the junior

member of the firm, an active, intelligent, warm-hearted fellow, who had

a prodigious love for the fine arts, and lived on familiar terms with

the Edinburgh artists. The visitor curious in the matter of art would

see nothing in the shop but the usual display of broadcloths and

bombasines, silk stockings, and spotted handkerchiefs, but on being led

down below into a kind of cellar, would find himself in a sanctum of

art, crammed with casts from the antique, books on art, such as Canova's

designs and Turner's Liber, and numerous specimens of the art of living

painters, such as William Allan and other painters of that period."

The Institution for the Encouragement of the Fine

Arts in Scotland was formed on the 1st of February 1819, under the

auspices of twenty-four directors, headed by the Duke of Argyll,

followed by the names of the Marquis of Queensberry, the Earls of

Haddington, Elgin, Wemyss and March, Hopetoun, Fife, &c. The first

exhibition of the Institution was opened on the 11th March 1819, in

Raeburn's gallery in York Place, and consisted of ninety-two pictures on

loan, including works by Vandyke, Titian, Velasquez, Rubens, &c., with

two or three British pictures by Richard Wilson, Reynolds, Alexander and

John Runciman. With regard to this movement, the late Lord Cockburn

remarks that "it introduced itself to the public by the best exhibition

of ancient pictures ever brought together in this country, all from the

collections of its members and their friends. Begun under great names,

it had one defect and one vice. It did little or nothing for art, except

by such exhibitions, which could not last long, as the Supply of

Pictures was soon exhausted. Its vice was a rooted jealousy of our

living artists as a body by the few who led the Institution. These

persons were fond of art, but fonder of power, and tried indirectly to

kill all living art and its professors that ventured to flourish except

under their sunshine." The subscribers to this Institution contributed a

single payment of £50, which constituted life-membership, and is

management was exclusively confined to the subscribers, no artist being

by its constitution allowed to serve on any committee, or to vote as one

of the governors while he continued a professional artist. A second

exhibition followed in 1820, but it did not fulfil the anticipations of

its promoters, and besides having drained most of the available

collections, the receipts drawn barely covered the expenses. The

dissatisfaction of the artists which existed at the commencement of the

Institution now began to be openly expressed, and the directors made

proposals that the artists should contribute to the next exhibition

under their auspices, and that the free proceeds would be set aside for

the benefit of the artists and their families—a plan which the artists

at the time accepted as a feasible one, the more particularly as it got

over the presidential difficulty with reference to the claims of Watson

and Raeburn, which had stood in the way of the three last modern

exhibitions.' The exhibition of 1821 was thus constituted a modern one,

and was opened on the 12th of March. Among the more prominent

attractions were Raeburn's portraits of Lord Hopetoun, and Lord

Kinnoull's gamekeeper; Geddes's portrait of Mr Oswald of Changue (a

lover of literature and art, secretary to the Institution, and who died

in April of the same year); a head of a boy with skins, by George

Simpson; an Ancient Procession and a Scene from 'Don Quixote,' by a

promising young artist named Wright; and sketches by Geikie. The

strength of the exhibition, however, lay in the landscapes, prominent

among which were A. Wilson's Evening in an Italian Harbour; Ruins of

Warwick Castle, by Patrick Nasmyth; the Pass of the Cows, by Alexander

Nasmyth; an Evening Landscape, by P. Gibson; Sea-pieces, by John Wilson,

then in London; the Castle of Heidelberg, by J. F. Williams; and

Edinburgh Castle, by Clarkson Stanfield. In the department of sculpture,

Chantrey was represented by busts of Lord Meadowbank and Mr Home of

Paxton; Josephs' and Scoular being also represented. A considerable

number of the pictures in this exhibition found purchasers, and a critic

of the time mentions, as indications of an increasing taste on the part

of the public, the numerous attendance at the exhibition, and the number

of pictures generally sold at that time in Edinburgh, stating that

within the few previous years London dealers had sold in Edinburgh old

pictures to the value of £5000. The directors at this time made known

their intention, if funds would ever permit, to build a suite of three

rooms for exhibition purposes, one of which would be devoted to the

works of ancient masters, and the other two appropriated to modern

pictures and sculpture.

Within the

following year (1822), an exhibition of beautiful and interesting

drawings in water-colours of Grecian scenery, by Hugh W. Williams, was

open in Edinburgh. It was highly appreciated, and, in consequence, well

attended; the catalogue was illustrated by quotations from the classical

authors appropriate to the subject of each picture.

The Institution's exhibitions thus constituted were

continued annually up till 1829, and in addition to those already

mentioned, the catalogues for the various years contain the names, among

others, of Wilkie, Thomson of Duddingston, John and George Watson,

Ewbank, Copley Fielding, Fraser (the elder), Howard, and Turner. The

discontent, however, on the part of the artists, instead of diminishing,

had gone on increasing, in consequence of the high-handed conduct on the

part of the directors still ignoring the artists in the management, and

culminated in 1826, when a movement was set on foot for the commencement

of a separate Scottish Academy. It was probably in anticipation of such

a movement that the Institution catalogue of that year sets forth the

objects of its promoters at considerable length, and which may be worth

extracting. "These objects embrace whatever may at any time appear

calculated to promote the improvement of the fine arts, by exciting a

more lively interest in their successful progress, by providing the

means from which a more general diffusion of taste in matters of art may

be expected to result, and by tending thus to increase the honour and

the emoluments of our professional artists. The Institution being

formed, not as a society of artists, but for their benefit, and for the

encouragement of art generally, it is proposed to have periodical public

exhibitions for the sale of the productions of British artists; to

purchase the works of modern artists, which, it is hoped, may of

themselves eventually form a most interesting exhibition; to excite

emulation and industry among the younger artists, by offering premiums

for their competition, and, by facilitating their exertions, putting it

in their power to visit London or other places, affording particular

means of improvement; to obtain, from time to time, for the study of the

artists and the gratification of the public, exhibitions of some of the

best works of the old masters that can be procured ; to establish a

library of engravings and books on art— an object which has already in

part been attained, and which is recommended to the Institution both by

the unquestionable utility of such a collection, and by its being one of

too expensive a description to fall easily within the reach of purchase

by private individuals; and finally, to serve the means of affording

relief to artists suffering under unavoidable reverse of circumstances,

or to their families when deprived by their death of the benefit of

their talent and exertions, and for which object also some provision has

already been made."

About the time at

which this long-winded explanation appeared in the catalogue, the

Institution was aided by a further notice in the 'Scots Magazine,' the

evident intention of which was to bias the public against the movement

being set on foot for the starting of the Scottish Academy. The article

tried to prove that the Institution was established on a basis superior

to that of the Continental academies. Referring to the latter the writer

says: The students who attend these are maintained at the public expense

till their education be completed, and their skill and reputation such

as are adequate to their support. This is not the way to breed either

original or liberal-minded artists, or to elevate the profession in

their own estimation or that of the public. But it is the way to breed

an esprit de corps and a peculiar style of art. The Royal Institution is

not founded on such a plan; it is not an association of artists; it is

an endowment merely of the means of improvement, of which the artists

may avail themselves if they incline. It is an emporium, in short, for

the exhibition and sale of their own works, and for the collection of

masterpieces for the improvement of their taste."

The Institution which thus made known its objects

consisted then (1826) of a hundred and thirty-one ordinary members,

thirteen honorary members, five of whom were artists, besides twelve

artists denominated Associate members.' The exhibition of that year was

held in the building known as the Royal Institution, which had recently

been erected at a cost of forty-five thousand pounds, defrayed from the

surplus granted at the Union. This grant, as already said, was placed in

the hands of a body of trustees in order to develop the industries of

Scotland, the leading members of which body were identical with those of

the Institution. Accommodation was provided for the School of Design

which the trustees had commenced in the Edinburgh College, and also for

the Royal Society and the annual exhibitions, both of which paid a

rent—the last-mentioned, £380.

The

movement for the commencement of the Scottish Academy was begun by the

circulation of a document by William Nicholson the portrait-painter, for

signature among the artists; and a meeting was held on the 27th of May

1826, Patrick Synie being in the chair, when a scheme was proposed, and

the Academy constituted by twenty-four artists : these were divided into

thirteen Academicians, nine Associates, and two Associate engravers. Of

these, however, nine resigned when they realised the responsibility

which they had incurred in joining the new body, and in consequence

another meeting was held on the 26th of the following December, when the

remaining fifteen courageously determined to risk an exhibition in

February. "The minutes of this meeting in the records of the Academy are

gratifying to peruse: no sign of quailing is shown by those present,

but, on the contrary, there is the expression of a quiet but resolute

determination to persevere as if all things were going on well. This

manly spirit was due very much to the firmness of purpose shown by Mr

William Nicholson and Mr Thomas Hamilton, who were the real founders and

promoters of the Academy." A council of four was now elected, consisting

of Thomas Hamilton, treasurer; William Nicholson, secretary; James

Stevenson; and Patrick Syme. For the three months required for the

exhibition, two large galleries, one somewhat smaller than the other,

were engaged in Waterloo Place for eighty guineas, but afterwards rented

at £130 per annum. After great efforts, not only to contribute

themselves, but also to obtain pictures from other artists in London and

elsewhere, the first exhibition of the Scottish Academy was opened

concurrently with that of the Institution, on the 1st of February 1827,

to which latter the majority, and, it may safely be said, the best of

the artists, still adhered, among whom were William Allan, Alexander

Nasmyth, Watson Gordon, and Grecian Williams. In the preface to the

catalogue it is stated that "it may no doubt be said that an Institution

for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Scotland already exists in

Edinburgh ; but while the intentions of its promoters are entitled to

every praise, it can only be regarded in the light of an auxiliary, and

ought not to supersede or repress the combined efforts of the artists

themselves. The Royal Institution, from its very nature, never can

supply the place of an Academy composed of professional artists, and

entirely under their own management and control. By confining itself,

however, to its original and legitimate objects, it may undoubtedly

render very essential services to the fine arts, whilst it may still

leave an ample field beyond the sphere of its operations which

professional men alone can occupy with advantage. . . . The members

declare they are actuated by no feeling of hostility to any existing

institution, and consider that the objects in view in which their own

interests are so deeply concerned, will be best attained by their own

exertions." The following notice also appears on the cover of the

catalogue :-

"I. Each Academician shall

give on his appointment 25 guineas to the funds of the Academy, and each

Associate io guineas. On an Associate being elected an Academician, he

shall give 15 guineas more to the same fund.

"II. Each subscriber of 25 guineas or upwards to be

called an Honorary Member, and to have free admission to all

exhibitions, and three friends, for life. Also access to the library,

collection of casts, &c., at certain periods to be afterwards specified.

"III. A subscriber of io guineas will be entitled

to free admission for himself and one friend to the annual exhibitions

of the Academy for life.

"IV. A subscriber

of 5 guineas will be entitled to free admission to the annual exhibition

for life."

The first exhibition contained

282 works, contributed by 67 artists. As great efforts had been made,

some of the artists, numerically at least, were well represented. J. B.

Kidd showed 15 works; W. Nicholson, 26; Ewbank and W. S. Watson, 13

each; D. Mackenzie, J. Syme, xi; T. M. Richardson, Newcastle, 9; J.

Stevenson, 8; George Harvey, Patrick Syme, and Miss Patrickson, 7 each;

the president G. Watson, Patrick Gibson (Dollar), A. Carse, and W.

Shiels, 6 each; J. Stewart (Rome), Geikie, and W. H. Lizars, 5 each; and

J. Graham sent one from Glasgow. The total amount of the pictures sold

reached the modest sum of £506.

Some

little animus was now shown on the part of the Institution, and in order

to strengthen its influence, the directors personally gave commissions

for pictures to those artists who were still its adherents. In point of

quality, as was to be expected, the exhibition of the Institution had

the best of it; but the new society of artists, finding the profits of

their first exhibition amounting to £317, 13s. 11½d., determined to

persevere, and the following year found them more equally matched, the

succeeding exhibition of 1829 fairly driving the Institution off the

field with William Etty's great picture of Judith and Holofernes (which

the Academy purchased), contributions from John Linnell, John Martin,

Sir Francis Grant, and the great picture of Rubens' Adoration of the

Shepherds, lent by Lord Hopetoun, and hung during the exhibition. This

picture being too large for admission by the door, had to be swung

through the cupola space—the cupola having been removed for the purpose.

The exhibition rooms in Waterloo Place were crowded, while those in the

Institution were so empty that a visitor one day surprised the officials

in charge utilising the vacant floor for a game at pitching pennies. The

artists who still adhered to the Institution, after for some time

maintaining the idea of forming with some others another association,

made a proposal through Henry (afterwards Lord) Cockburn that they

should be received into the membership of the Scottish Academy on the

rank of Academicians, submitting to the already constituted

rules—William Allan, R. Scott Lauder, and W. J. Thomson being willing,

however, to rank only as Associates. On receiving this proposal the

Academy, fearing that their constitution might be overturned by so many

full members entering at once, and being at the same time unwilling to

shut the door in the faces of their fellow-artists, consulted Mr Hope,

the Solicitor-General, on their part. And these two lawyers, after some

consulting and negotiating, "married them in a week." The new members

were now admitted, and the permanence of the rules and constitution was

ensured by an able and ingenious arrangement, which was unanimously

approved on the 10th July 1829; Mr Lizars, the engraver, resigning at

this time, in consequence of a rule which was afterwards abolished, by

which engravers were limited to the rank of Associates.

The directors of the Institution being unwilling to

abandon the field altogether, now proposed to the Academy that its

members should contribute to their exhibition in the following February—

a proposal which, of course, was rejected; the members of the Academy,

however, expressing their willingness to do so to one for the sale of

works by living artists during the summer months. An exhibition of this

nature was accordingly opened by the Institution on the 1st May 1830,

but was not successful; on which the Institution as an exhibiting body

sank into obscurity, after having by its tyranny produced the Scottish

Academy. Under the new arrangement the

first general meeting of the Academy was held on the 11th of November

1829, at which the office-bearers required to be elected. The arbiters

had recommended that the existing office-bearers should retain office

for some time, on account of the great number of acceders recently

admitted, so as to weld together the new and the old elements of the

Association; but the ballot substituted the name of John Watson Gordon

as treasurer for that of Thomas Hamilton. This was at the time thought

rather ungraceful, Mr Gordon being one of the newly admitted members,

while Mr Hamilton had from the very commencement of the movement been

one of the most energetic promoters of the Academy. In the following

year Mr Nicholson resigned his office as secretary, on account of the

great amount of time required for his now considerably augmented duties.

Mr D. O. Hill being elected in his stead, filled that office till his

death, which occurred nearly forty years later.

The important picture of Judith and Holofernes,

already mentioned as having been purchased from Etty in 1829, was paid

for before the close of the exhibition, and an arrangement was further

made with the same artist to paint two side-pieces for that picture. The

series being completed on very liberal terms on the part of Etty, the

members of the Academy resolved to exhibit them in December 1830, along

with their own diploma pictures, and others borrowed from Etty. In

accordance with their request, he sent his Benaiah, and the

Combat—borrowed from the owner, John Martin the artist—besides three

small pictures, consisting of a Venetian Window during Carnival, Nymph

fishing, and the Storm. The idea of acquiring for the Scottish National

Gallery the three first-mentioned large and important pictures was

suggested by Hamilton, Macleay, and George Harvey. Hamilton having

written privately to Etty, found that the Benaiah could be had for 130

guineas, and that Martin would part with the Combat for £400 The Academy

decided UOfl the purchase, not without opposition on the part of some

dissentients, including the treasurer, who resigned in consequence.'

Even as a commercial transaction, however, the wisdom of the purchase

was soon apparent, the sum Of £2500 having been offered some years

afterwards for the Combat alone. Such was the low appreciation of Etty's

work in England at that time, that although so modestly priced, the

Combat passed unsold through the Royal Academy's exhibition, his friend

John Martin purchasing it at the last hour for £300.

The exhibitions of the Institution, which, as

already said, ceased in 1829, had been held in the main gallery of their

building, and the members of the Academy continued their exhibition in

the Waterloo Place Rooms till the expiry of their lease in 1834. During

this time the Board of Trustees acquired and placed in the Institution

rooms the greater part of their collection of pictures, towards the

formation of the National Gallery. The attendance of the public was

small, and during the time of their exhibition the valuable suite of

rooms was almost entirely vacant during the other nine months of the

year, the gloom being only broken in upon for a short time by the

exhibition of the skeleton of the great northern whale, notwithstanding

their advertisement: "To be let, for exhibition of pictures, or other

articles connected with the fine arts, the above elegant apartments." 1

On the expiry of the lease of the Waterloo Rooms, advances were made in

1835 by the Institution towards the Academy, which resulted in the

exhibitions of the latter being transferred to the Institution's

building, for which a rent of £100 was paid, and a further like sum for

the use of the Board room, which was felt to be rather severe upon the

Academy, the members having thus even to pay for permission to see the

pictures by Etty, which they had bought and deposited there, the

Institution at the same time receiving a grant from Government of £500

per annum. The exhibitions of 1836-37 were limited to the north octagon

and central gallery; in 1838 the Trustees offered in. addition the south

octagon for the ensuing exhibition, and subsequently on application the

south-west room was also added.

Things seem now to have gone on tolerably

smoothly with the Academy for a few years. In 1837 it lost its first

president by the death of George Watson; William Allan being elected his

successor, and receiving the honour of knighthood when he succeeded

Wilkie as Queen's Limner for Scotland, in 1842.

Immediately after the institution of the Academy,

and within its first year, an application was made to the Home

Secretary, Mr Peel, for a charter of incorporation, which was refused,

although warmly supported by Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A.; the Academy

meanwhile having the mortification of seeing that distinction soon after

bestowed on the Institution. Application was again made, and after much

trouble on the part of its office- bearers and friends, it received its

charter on the 13th of August 1838, as the "Royal Scottish Academy of

Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture,"—" thenceforth to consist of

artists by profession, of fair moral character, high reputation in their

several professions, settled and resident in Scotland at the dates of

their respective elections, and not to be members of any other society

of artists in Edinburgh." The charter ordains that there shall be an

annual exhibition of paintings, sculpture, and designs, in which all

artists of distinguished merit may be permitted to exhibit their works,

to continue open for six weeks or longer. It likewise ordains that, so

soon as the funds of the Academy will permit, there shall be in the

Academy professors of painting, sculpture, architecture, perspective,

and anatomy, elected according to laws to be framed in accordance with

those of the Royal Academy in London; and that there shall be schools to

provide the means of studying the human form, with respect both to

anatomical knowledge and taste of designs, which shall consist of two

departments, the one appropriated to the study of the remains of ancient

sculpture, and the other to that of living models.' For the school of

art thus contemplated in the Academy's deed of constitution, it was also

provided for thus: that the use of an apartment for these purposes shall

be afforded either by the Board of Trustees or the Institution, at such

seasons as may not interfere with the annual exhibitions of manufactures

or meetings of the Board; and in addition, access to the collection of

casts belonging to the Board is to be afforded, to enable the Academy to

conduct its proposed school of the antique. Thus, the class for drawing

for manufactures which the Board had long possessed, was now to be

supplemented by others for the higher branches of art, conducted under

the auspices of the great body of Scottish artists, and the supervision

of the Board. Obstructions, however, were again thrown in the way. A

wretched little room in the basement storey was pointed out to the

Academy for the life-school, which, after trial, had to be abandoned as

unfit for the purpose; while at the same time the south octagon, as well

as the west room, well fitted for the purpose, remained useless and

unoccupied nearly all the year round. In one of these apartments the

Academy's pictures had been placed according to agreement, but after a

few months, were taken down that the room might be painted, and not put

up again there, but placed among the pictures of the Institution in the

north octagon, a fee being charged for admission to see them. The

Academy was thus compelled to rent two rooms in Register Street for the

continuance of their life-school, the expenses of which, together with

their purchases for the National Gallery, library, &c., were defrayed

from the Proceeds of the exhibitions.

The

struggles of the Academy were not yet over, and the feeling so long

existing between the Board of Trustees and the Royal Institution on the

one part, and the Academy on the other, reached an extreme point of

virulence in 1846, when the latter body received intimation that only

two of the four rooms previously occupied would in future be placed at

their disposal for their exhibitions. The Academy endeavoured to show

that even the four rooms were inadequate, sculpture being almost quite

excluded, and declined to accept the limited accommodation offered for

the future. As already stated, the gentlemen constituting the Board of

Trustees and the Institution were almost identical—so intimately mixed,

indeed, that Sir George Harvey mentions that one gentleman who generally

took the lead, was heard to assert with emphasis, that he was the Board

of Trustees and the Royal Institution also. The Academy had thus to

contend with one antagonist under two names, with separate and yet

united powers. As the members of these two bodies were mostly men of

high social standing and unimpeachable character, it can only be

believed that they took little personal interest in the affairs of the

Board and the Institution; and consequently, whatever blame they may

have incurred, was due to the petty annoyances caused by the executive

and their own carelessness. The source of these annoyances has been

largely attributed to the change of position of a picture from a fair to

a worse place on the wall of one of the exhibitions, during the hanging

and before it was opened. The picture was by a son of Sir Thomas Dick

Lauder, the secretary of the Board, who made it the subject of an

official correspondence (19th Feb. 1844), expressing himself in his

first letter so bitterly as to characterise the council as a body which

allowed its judgment "to be swayed and overturned by every unworthy

intrigue that may be originated by selfish individuals in the body which

it ought to govern."' Among other hard things said, the Board described

the Academy council as "a series of individuals changed every year, and

of whose habits, and even names, they are ignorant;" while alluding at

the same time to the Royal Society, the Society of Antiquaries, and the

Royal Institution as consisting of persons of the highest

consideration.' The series of obscure individuals, consisting of Sir

William Allan, R.A., John Watson Gordon, Thomas Hamilton the architect,

&c., vindicated their action. The picture was admitted to have been

placed at first in the position from which it was moved, but one of the

members pointing out that it hurt the colour and appearance of the wall

while ignorant of the artist's name), it was moved to another place on

the responsibility of the hanging committee and council.

The result of this action on the part of the

Board was a vigorous movement in 1847 towards the erection of a suite of

rooms suitable for all the purposes of the Academy and the National

Gallery; and after many applications to the Treasury for State aid

towards this object, a commission was sent from the Treasury to report,

the city having in the meanwhile granted a site at the almost nominal

sum of £1000. In the spring of 1850, John Watson Gordon was knighted,

and elected president on the death of Sir William Allan; and in August

of the same year a vote was moved in the House of Commons for the

buildings, but negatived, chiefly by the opposition of Hume and Bright.

Explanations, however, having been given privately to these gentlemen,

the vote was again brought up and passed, for £30,000, in addition to

£20,000 from the Board of Manufactures, for "a distinct edifice properly

adapted for their objects and functions, and appropriated to their own

use, upon conditions analogous to those under which the Royal Academy in

London have the advantages of their present galleries." Designs for the

proposed edifice having in the meantime been prepared by William

Playfair, the foundation- stone was laid by Prince Albert on the 3oth of

August 1850, and the buildings were completed in 1855, in which year the

Academy held its first exhibition there.

The general custody and maintenance of the buildings are vested in the

Board of Manufactures, the Royal Scottish Academy having the entire

charge of the council-room and library, and of the exhibition galleries

while open to the public. The troubles of the Academy were now fairly

over, and it henceforth entered upon a deservedly successful career, as,

besides having obtained a permanent local habitation, its funds were

further augmented by the saving of the rent previously paid to the Royal

Institution, which had latterly increased to £700. It had thus obtained

what Lord Cockburn, one of its ardent promoters, had long before set his

mind upon, when in 1838 he wrote, "I want £300 a-year, a charter, and

under the Queen's patronage the title of the Royal Academy. I have

nearly succeeded twice, and I don't despair. Why should we, who have

done more than London relatively, and more than Dublin absolutely, not

get what they have?" The artists in the latter city, it may be added,

had to pass through pretty much the same ordeal.

This first exhibition in its permanent premises,

being its twenty- ninth, closed on the 2d of June, having been a month

later than usual in opening in consequence of the galleries not being

ready in time. It was undoubtedly the finest which Edinburgh had

witnessed, containing important works by Stanfield, Linnell, Land- seer,

Cooke, Poole, and Millais, representing the English artists; while

native art was worthily represented by Harvey, MacCulloch, Bough, Noel

Paton, the Faeds, the Landers, Gordon, &c., in painting-and in sculpture

by Marshall, Brodie, Ritchie, and others. About 1300 season tickets were

purchased, and nearly 27,000 persons paid at the door during the time in

which it was open in the evenings; while nearly 3000 season tickets were

sold, and over 25,000 people paid at the door for the day exhibition,—

making a total of 52,000 paying at the door, and nearly 4300

season-ticket holders.

Sir John Watson

Gordon, its third president, dying in 1864, was succeeded by Sir George

Harvey. Sir Daniel Macnee followed in 1876; on the death of whom six

years after, the present accomplished Sir William Fettes Douglas was

elected to the honourable position.

In

July of the year 1825, Mr Peter Spalding of Heriot Row, who had been

superintendent of the Mint at Calcutta, executed a will in which he left

his fortune to the directors of the Institution for the Encouragement of

the Fine Arts in Scotland, for creating a fund, the interest or annual

proceeds whereof, to be applied for ever for the support of decayed and

superannuated artists belonging to the Institution. The testator died on

the 16th October 1826, when the value of the bequest amounted to about

£10,000. The interest of the bequest continues to be administered by the

Academy in accordance with the intentions of the donor, the annuities

given usually amounting to about £30 each. Further bequests have since

been made, among which may be mentioned that of Mr Alexander Keith of

Dunottar, who left a legacy in 1852 of Li coo for the purpose of

promoting the interests of science and art in Scotland. The trustees

appointed (Sir David Brewster and Dr Keith), from this sum appropriated

£600 to the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and £400 to the Royal Scottish

Academy—the interest to be given for "the most important discoveries or

inventions connected with these Societies." This small bequest, has been

utilised in the form of prizes awarded to students in the life-class of

the Academy; the "Stuart" prize, another bequest, being devoted to the

same purpose. Besides these, the sum of £1000, bequeathed by the mother

of the late George Paul Chalmers, is applied by the Academy in the form

of a bursary.

In addition to the many

valuable pictures, &c., lent to the public in the National Gallery, the

Academy possesses a fine and numerous collection of drawings by the old

masters, bequeathed by the late Dr David Laing; drawings of various

kinds; life studies by Etty; besides other works of varied interest, and

the prize studies by students of the life-school from 1873 onwards. The

value of all its art property is estimated at over £40,000. It also

possesses a valuable collection of books, forming a good art library.

The following are extracts from its present constitution and laws:

SECTION I.

"1. The members shall form three Orders or

Ranks.

"2. The first Order shall consist of thirty

members, who shall be called Academicians of the R.S.A.; and of this

Order, engravers not exceeding two may be members.

"3.

The second Order shall consist of members not exceeding twenty, who

shall be called Associates of the R.S.A.; and of this Rank, engravers

not exceeding four may be members.

"4. The members of

both these Orders shall be professors of Painting, Sculpture,

Architecture, or Engraving, and Artists by profession; men of fair moral

character, of high reputation in their several professions, settled and

resident in Scotland at the dates of their respective elections, and who

shall not then, or thereafter, be members of any other Society of

Artists established in Edinburgh.

"5. The third Order

of members shall be called Honorary Members.

"6. Among

these shall be a Chaplain, of high reputation as a minister of the

Gospel, a Professor of Ancient History, a Professor of Ancient

Literature, and a Professor of Antiquities, men of distinguished

reputation.

SECTION II.

"1. The

government of the Academy is vested in a President and Council, and the

general assembly of Academicians.

"2. The President

shall be annually elected, and shall preside at all general assemblies

of Academicians and meetings of Council.

"8. The

Council shall consist of six Academicians and the President, who shall

have the entire direction and management of all the business of the

Academy.

"10. The seats in the Council shall go by

succession to all the Academicians, except the Secretary, who shall

always belong thereto. The three senior members of the Council shall go

out of office by rotation every year, and three shall come into it

annually, in the order in which they originally were members of Council.

"11. The newly elected Academicians shall be placed at the top of the

list, and serve in the succeeding Council.

"25. There

shall be annually one general meeting, or more if requisite, of the

whole body of Academicians, to elect a President, declare the Council,

elect a Secretary or Treasurer, &c., &c.

SECTION Ill.

"1. There shall be a Secretary elected annually by ballot from amongst

the Academicians; &c.

"4. There shall be a Treasurer

elected annually by ballot from among the Academicians; &c.

"16. Four Academicians shall be elected annually to be visitors to the

Life-School.

SECTION IV.

"1. All

vacancies of Academicians shall be filled up by election from among the

Associates.

"11. No Academician-elect shall receive his

diploma until he hath deposited in the R.S.A. (to remain there) a

picture, bas-relief, engraving, or other specimen of his abilities,

approved of by the sitting Council of the Academy.

"12.

The Associates shall be at least twenty-one years of age, and not

apprentices.

"13. Associate Painters, Sculptors, and

Architects shall be elected from among the exhibitors in the Annual

Exhibitions.

SECTION V.

"1. Every

Associate shall, on his election, pay into the funds of the Academy the

sum of fifteen guineas. On being elected an Academician he shall pay ten

guineas more.

"7. The existing stock and property of

the Academy, and all additions that shall be made to it, shall always

remain dedicated and set apart for the purposes of the Academy; and no

division of such funds among the members, or application of them

partially, or at once, to any objects in which members are personally

interested, shall be competent under any circumstances.

"13. Not less than one-third of the gross annual income of the R.S.A.

shall be applied annually towards the formation of a fund to be called

the Pension Fund,

"14. The sum so to be applied shall,

with the sum obtained from the Royal Institution, and with the sum

already applied for this Fund, and with the annual interest, be annually

accumulated until the Fund shall amount to £6000, when the Council shall

have power, out of the annual interest or revenue of said capital sum,

to give pensions to Academicians, Associates, and the widows of

Academicians and Associates.

"18. Any Academician or

Associate who shall for two successive years omit to exhibit a fair

proportion of his works to the annual exhibitions, shall have no claim

on the Pension Fund unless he has given satisfactory proof that the

default was occasioned by illness, &c.

"20. No sum

exceeding £25 shall be granted by the Council within the term of one

year to any Scottish Academician, Associate, or other person whatever,

without the ratification of the general assembly.

SECTION V*.

"1. Every Academician, on arriving at sixty

years of age, shall be entitled to participate in the Pension Fund.

"2. The widow of an Academician shall be entitled to participate in the

Pension Fund. (Rules 1 and 2 also apply to Associates.) 116. An

Associate, or his widow, shall be entitled to participate in the

proportion of three-fifths of the amount given to an Academician or his

widow.

"7. (Provides for temporary relief.)

SECTION VI.

"2. Any member being a director of, or

holding an official situation in, any other society for the exhibition

of pictures in Edinburgh, shall not be eligible to an official situation

in the R.S.A., and shall be disqualified from attending its meetings,

and shall not have access to the books of the Council and general

meetings.

"3. Every Academician shall have the

privilege of recommending proper objects (artists, widows, or their

children) for charitable donations, accompanied by a certificate, &c.

SECTION VII.

"4. No prints shall be admitted into the

exhibitions but those of the Academicians and Associates who are

engravers.

"'5. Whoever shall exhibit with any other society (in

Edinburgh) at the time when his works are exhibited in the exhibition of

the R.S.A., shall neither be admitted as a candidate for an Associate,

nor his performances be received the following year."

Note.—For some time past the charter of the Academy has been in process

of revision, and a new one has been now drawn up awaiting the Royal

sanction. The intentions of the new charter are chiefly, that the

Academy should be authorised to admit a larger number of Associates than

are at present admissible; that the Associates should be authorised to

share in the election of Academicians and Associates; that certain

powers now vested in the council of the Academy should be vested in the

assembly of Academicians, and certain powers now vested in the assembly

of Academicians and in the council, should be vested in the general

assembly of the Academy, &c. It is intended that the Academicians shall

have power to alter the present or make other rules, provided they are

in harmony with the supplementary charter; and that if any Academician

is resident out of Scotland for three years, the vacant place may be

filled up, so that there may always be thirty Academicians resident in

Scotland. There is no limit proposed to be put on the number of

Associates, and it is intended at present that a certain number only of

that rank, in the order of seniority, shall be entitled to participate

in the pension fund. The general scope of the new charter is thus to

widen out the usefulness of the Academy, by allowing the Associates

certain powers in its government which they do not at present possess,

to increase their number and position, and to enable the Academy more

thoroughly to raise the position of art in Scotland. |