IN the latter part of the seventeeth century, one

of the resorts of the fashion and beauty of Edinburgh was on the east

side of the Advocates' Close, where John Scougal the painter rented or

owned a house, to which he had added an upper storey arranged as a

studio. He was of a respectable family, being cousin to Patrick Scougal,

consecrated Bishop of Aberdeen in 1664, whose son, the Professor of

Divinity there, was spoken of as sometimes loving God and sometimes

loving women. Scougal had a very extensive practice, which latterly led

him into a hasty style of work, said to be observable in the portrait of

George Heriot, which he copied in 1698 from the now lost original by

Paul van Somer. He has left a portrait of Sir Archibald Primrose, Lord

Clerk Register, in the possession of Lord Rosebery, dated 1670, and two

of the ancestors of the Clerks of Penicuik, four years later. Several of

his works were in the possession of Andrew Bell the engraver, who

married Scougal's granddaughter, and who died within the present

century; in Leith, wherein he is said to have been born, are several of

his works of an inferior quality; and in the Glasgow Collection are

three full-lengths, removed from the old Town Hall, consisting of

William III., Queen Mary, and Queen Anne. Of these, the Queen Mary is by

far the best—well drawn, good in colour, and suggestive of the influence

of Vandyke's work. From the Glasgow Town Council minutes of 12th March

1708, it is ascertained that the purchase by the Provost of the William

and Mary from "Mr Scougal, limner in Edinburgh," for £27 sterling, was

approved of; and the money ordered to be paid by the treasurer for

transmission to the artist. Payment for the Queen Anne was ordered to be

made on the 2d August 1712, to "John Scougall, elder, painter, fifteen

pounds sterling." [Mr Paton's Catalogue.] He died at Prestonpans about

the year 1730, after witnessing some of the most important changes which

ever occurred within the history of his country, having lived to the

mature age of eighty-five years. [Dr Wilson's Memorials of Edinburgh.]

His name has been sometimes mentioned erroneously as George, [Probably

for the first time in the Weekly Magazine, vol. xv.] and another painter

of the same name is the credited author of his own portrait in the

Scottish National Gallery, a careful, brown Vandyke-looking head, in

which the artist, spoken of as the "elder" Scougal, is represented in a

high collar of Charles I. period, and holding in his hand a ring, said

to have been the recompense bestowed on him by James VI. for painting a

portrait of Prince Henry. As any other traces of an "elder" Scougal are

unknown, and this portrait was presented by a descendant, John Scougal

of Leith, it is not unreasonable to suppose that it is a fancy portrait

of the same artist, to whose work it bears a tolerable resemblance. This

supposition, that there was only one artist of the name, is readily

borne out by the long life enjoyed by the artist, the error in name

referred to, and the fact that one of the Glasgow payments was made so

late as 1712 to "John Scougall, elder, painter." To assume otherwise,

there is only the evidence of a vague tradition unsupported by fact, and

the existence of the inferior portraits at Leith bearing the same name.

It is evident from the Glasgow Council minute that he had a son of the

same name, but it by no means follows that because he was called elder

or senior in money transactions, the son also was an artist.

Practising about the same time as Scougal, was Corrudes, a foreign

painter of portraits, of whom even still less is known, and after him,

Nicholas Hude. The latter is usually considered to have been a French

artist, as he was formerly one of the directors of the French Academy,

obliged to leave France on the repeal of the Edict of Nantes. [Hude

is the old Scottish form of spelling Hood. In the Reformation period,

statutes were directed against the exhibition of Robert Hude (Robin

Hood) and the Abbot of Unreason.] After his arrival in London,

about 168, where he remained several years unemployed, William, Duke of

Queensberry, brought him to Scotland to do work for him at Drumlanrig

Castle. He is said to have been a not unsuccessful imitator of Rubens,

and although more inclining to historical painting, was for a livelihood

compelled to paint portraits. Two native artists of about this period

have left little more than their names and a few obscure works. These

were Paton, who painted several portraits in oil, but better known by

his copies and miniatures, and black-and-white drawings, which were said

to possess a good deal of likeness and expression. The other was Richard

Wait, an assistant of Scougal, who painted portraits between 1708 and

1715, and also some pieces of still life. [The Bee.]

He practised in Edinburgh, and there formerly existed at Newhall House a

whole-length portrait of the Old Pretender in the archers' uniform,

dated 1715, by him. [Introduction to Gentle

Shepherd, 1808.]

By far, however, the most fashionable artist

in Scotland at the close of the seventeenth and beginning of the

eighteenth century, was Juan Bautiste Medina, better known as Sir John

Medina, having the distinction of being the last knight created prior to

the Union, which honour was conferred on him by the hand of the Lord

High Commissioner Queensberry. The very numerous portraits which he has

left us is proof that he pursued a very successful career; while the

quality of his work, although hard and often weak in drawing, entitles

him to the not inappropriate designation of the Kneller of the North,

which is sometimes bestowed on him. His father, a Spanish captain from

the Asturias, had settled in Brussels, where Juan was born in 1659, and

received his art education from Duchatel. He married a Flemish wife

named Joan Mary Vandael, and came over to London, where he remained

about two years practising portrait- painting in the short reign of

James II. David, Earl of Leven, having procured for him promises of

portraits to the amount Of £500, induced him to come to Scotland at the

close of James's reign, bringing with him, according to Walpole, a

number of bodies of figures already painted, to which he added heads as

sitters offered. The last statement must, however, be received with some

caution. He remained almost entirely in Scotland till his death in 1710,

and was buried in Greyfriars Churchyard in Edinburgh, leaving property

to the value of £13,130, 16s. and 3d., equal to about £1,300 sterling.

During these twenty-one or twenty-two years, it is said he painted about

half the nobility of Scotland, as well as many of the eminent men of his

time. The residence of the Earls of Leven contains about twenty of his

portraits, including one of the first Earl of Melville, State Secretary

for Scotland. "Of the beauties of the family, for whose fair heads

Medina had the honour of finding bodies," says the accomplished author

of the 'Annals of the Artists of Spain,' who was connected by marriage

with the Melville family, "the most pleasing are a pretty Lady Balgonie

of the house of Northesk, and the lovely Margaret Nairne, wife of Lord

Strathallan, slain at Culloden, and herself imprisoned in Edinburgh

Castle for her Jacobite loyalty. The first Duke of Argyll was also one

of his patrons; and he painted a large and excellent picture of that

nobleman and his two sons, both Dukes in their turn—John, who claimed

the victory of Sheriffmuir, and lives in the lines of Pope and the

romance of Scott, and Archibald, better known as Lord Ilay, Walpole's

viceroy beyond the Tweed. The Highland heads of these chieftains Medina

fitted upon Roman bodies; and he represented the sire in boots of

lustrous brass, giving a laurel wreath to his eldest boy, thus

vindicating his claims to the national faculty of second-sight, as he

stands pictured among his ancestors at Inveraray. He also painted a

large family group for the gay Gordon, who held out Edinburgh for James

IL, and numerous other portraits throughout the mansions of the Scottish

nobility." [Stirling's Annals of the Artists of

Spain.]

Medina's practice was by no means confined to

portrait-painting, and mention occurs of several of his works of various

kinds in some collections which were formed in his time. At Amisfield in

Haddington, the property of the Earl of Weniyss, in a list of a hundred

and thirty-three pictures, mostly by the old masters, and fifteen family

portraits, [Transactions of Scottish Antiquaries,

1792.] in 1792, were six works bearing his name; the largest were

a St Jerome, and Apelles and Campaspe, fully four feet square, the

others being two children, landscape with figures, &c. At Newhall House,

which in 1703 was sold to the eminent lawyer Sir David Forbes, brother

to Duncan Forbes of Culloden, were five pictures, consisting of a Venus

chastising Cupid, Diana and Endymion, two upright landscapes with

figures, and a man drinking by candlelight. [Preface

to Gentle Shepherd, 1808.]

With regard to his prices, it was

found at his death that his highest-priced portrait was that of the

Countess of Crawford and her son, at Lb sterling; his lowest being £3

for a copy of his own work. It would be curious to know if this artist

was a descendant or relation of the Jan Gomez de Medina, captain of

twenty hulks of the Spanish Armada, whose ship was wrecked off the north

coast of Scotland, and who sought shelter and protection from James

Melville, the minister of Anstruther. The grave old sea-captain

afterwards, we are told, possessed a warm heart to Scotland.

John

Medina, a son of the knight, also followed the art, and seems to have

been mostly occupied in painting portraits of Queen Mary, and spending

the proceeds with other gay young bloods in the then popular

oyster-cellars of Edinburgh. In a poetical epistle written by David Hume

in 1746-47, the painter is invited to draw the picture of some unknown

individual, accompanied with grotesque attributes. It begins—

Now dear Medina, honest John,

Since all your former friends are gone,

And even Macgibbon's 'turned a saint,

You now perhaps have time

to paint.

Draw me a little lively knight,

And place the figure

full in sight,

With mien erect, and sprightly air,

To win the

great, and catch the fair."

The last stanza concludes thus—

No more obliged, for twenty groats,

To draw the Duke, or Queen of

Scots;

Your name shall rise, prophetic fame says,

Above your

Mercers, or your Ramsays;

Even I, in literary story,

Perhaps

shall have my share of glory."

Still another John Medina seems to have

practised painting, whom Sir Wm. Stirling-Maxwell assumes as a grandson

of the first, and who is only known by the fact that he exhibited in the

Royal Academy in London in 1772 and 1773. Both of these are said to have

been inferior artists.

It is somewhat remarkable that while some

foreign artists were tempted to settle and practise their art in

Scotland at this period, several Scottish painters sought employment for

their talents abroad, not unsuccessfully. Among the earliest of these

was Thomas Murray (1666-1724), whose portrait hangs among those of the

other artists at Florence, and which has been engraved in the Museo

Florentino. He was remarkable for his personal beauty, it is said, and

for the elegance of his manner, and died what may be considered rich for

an artist, owing to success in his profession. He studied under and

assisted John Riley, painter to William and Mary, and was subsequently

largely employed by the nobility and the royal family. His practice was

exclusively confined to portraits —that of Dr Halley at the Royal

Society, and one of Wycherley possessed by the Earl of Halifax, being

mentioned by Walpole. As was naturally to be expected, his style

partakes little of that of his predecessors in Scotland, or of the

subsequent painters of the Scottish school.

Almost contemporaneous

with Murray, rather earlier, occurs the name of William (G.?) Ferguson,

of whom little is known beyond a few facts and dates. He was a good

artist for his time, fond of painting subjects allied to still-life,

although he sometimes ventured on out-of-door scenes, an example of

which is in the Scottish National Gallery. This consists of classic

ruins in strong light and shade, generally well though unequally

painted, with some peasants in the foreground of no great merit. Two

groups by him still form part of the collection at Newhall House, and

consist of partridges and other small birds. He is supposed to have

acquired the rudiments of his art in Scotland, but early went to the

Continent, where he lived so long, chiefly in Italy, that he has left

little more than a reputation in the country of his birth. He is

understood to have died in London about 1690.

The name of a Scottish

artist of the seventeenth century occurs in the English annals of art—J.

Michael Wright—who is almost unknown in the country of his birth. He is

said to have received some instruction from George Jamesone, and

migrated to London when about the age of sixteen or seventeen, where he

seems to have very rapidly risen into prominence. Although he is rather

slightingly mentioned by Pepys, he was a painter of very considerable

ability. The date of his birth is not known: it has been assigned to

about 1655, but this is evidently too late a date, as he painted in 2672

a whole-length portrait of the cavaliering Prince Rupert, wigged and

armoured; on the back of which, in addition to the Prince's titles, he

inscribed, "Jo. Michael Wright, Lond., Pictor Regius, pinxit 1672." In

the same year he painted another full-length of Sir Edward Turner,

Speaker of the House of Commons and Chief Baron, which he inscribed

"Jos. Michael Wright, Anglus 1672"; and about the same time some

Guildhall portraits of judges, on which Scotus is written after his

name. It is said that the commissions for the latter came to him on

account of Sir Peter Lely declining to paint the judges in their own

chambers, and for these he received sixty pounds each. Subsequently he

painted other full-lengths, notably a Highland laird and an Irish Tory,

of which replicas were made. Windsor formerly contained (possibly still

does) a large full-length picture in which John Lacy, the celebrated

comedian, is represented in three characters—as Parson Scruple in the

"Cheats," Sandy in the "Taming of the Shrew," and Monsieur de Vice in

the "Country Captain." This was painted in 1675, and the Redgraves refer

to it as being a fine work, imitatively painted and low in tone, the

figures being simply and well grouped) He is also known as the painter

of two portraits of a Duke of Cambridge, probably the two sons of King

James, who each bore that title. As steward of the household to Lord

Castlemaine, he accompanied an embassy to the Pope, probably on account

of being able to speak Italian, having been in Italy before. An inflated

account of this mission was published both in Italian and English by the

painter on his return to London. He is mentioned by Orlandi as "Michaele

Rita Inglese, Notato del Catalogo degli Academici di Roma, nel anno

1688," at which city he left a son, a master of languages, and where

also he educated a nephew in his own art, which he successfully

practised in Ireland. He was a purchaser at the sale of the pictures of

Charles I., and possessed a collection of gems and coins, which were

purchased after his death by Sir Hans Sloane, and deposited in that

gentleman's museum of antiquities. Wright, on his return from the Roman

embassy, was annoyed to find his practice in his absence engrossed by

the fashionable Sir Godfrey Kneller; and in 1700 solicited from the king

the then vacant appointment of King's Limner in Scotland, encouraged no

doubt, in addition to his artistic position, by having executed the

painting on the ceiling of the royal bed-chamber at Whitehall. The royal

commission, however, was bestowed upon a shopkeeper, whose name and

claims are probably not worth searching out.

As already mentioned,

Arnold Bronkhorst was the first appointed to this office in 1580, and in

the reign of Charles II. it seems to have been held by David de Grange,

a miniature-painter, who in 1671 petitioned that monarch for "76 li. due

for work done in Scotland for his Majesty." In his petition, which was

referred to the Lords of the Treasury, who took no notice of it, the

limner mentions having received from the king 40s. when he lay ill at St

Johnston's, and afterwards 4 Ii. from Sir Daniel Carmichael, the deputy

treasurer. In urging his suit he mentions "the pressing necessities of

himself and miserable children; his sight and labour failing him in his

old age, whereby he is forced to rely on the charity of well-disposed

persons." A schedule delivered in 1651, during the royal residence at St

Johnston's in Scotland, accompanied the petition. In a list of placemen

in the columns of a contemporaneous magazine, the name of James

Abercromby appears as "Captain of Foot, King's Painter in Scotland, M.P.

for Banffshire, and Deputy Governor of Stirling Castle; drawing six

hundred pounds per annum in 1739. The duties sometimes required of an

artist under royal patronage in these times are curious and difficult to

define. The office of sergeant painter, which was held by several

eminent artists at the English Court, was filled by John de Critz, who,

in the reign of James I. and Charles I., not only had to paint royal

portraits for transmission to foreign potentates, but had also to gild

weathercocks, and paint and gild his Majesty's barge. This office,

however, was inferior to that of king's limner, which was one of very

considerable value to the recipient at that time, although it has now

become a mere formal and complimentary appointment. When Nicholas

Hilliard, the English miniaturist, after the death of Queen Elizabeth,

enjoyed the still greater favour of her successor, this well-beloved

servant received a patent in which this "our principal drawer of small

portraits and embosser of our medals in gold" had granted unto him a

special licence for twelve years, during which time no one was permitted

to "invent, make, grave, and imprint any pictures of our image or our

royal family . . . without his licence obtained;" which of course was of

great value, as he engraved many plates with the heads of the king and

those of members of the royal family: impressions of these he sold, as

well as licences for others to do likewise. That there was also a salary

accompanying the office at times, there is instance in the appointment

of Daniel Mytens, who, as his Majesty's picturerto James VI. and

Charles, painted many of the Scottish nobility, the latter monarch

having given and granted to the "said Daniel Mittens the office or place

of one of our picture drawers of our chamber in ordinary, . . . to have,

houlde, occupy and enjoy, . . . for and during his naturall life," with

the "yearlie fee and allowance of twcntie pounds of lawfull money of

Englande by the yeare, . . . at the foure usuall feasts of the yeare, .

. . together with all and all manner of-other fees, profitts,

advantages, rights, liberties, commodities, and emoluments whatsoever to

the said office or place belonginge or of righte appertayneing;" an

office which that artist, however, only held till supplanted by Vandyke,

although not losing the royal favour otherwise.

Another artist falls

to be mentioned, John Alexander (born 1690, died 1760), of somewhat

later date, and of whom some little uncertainty has existed, especially

as to the date of his birth. He was a descendant of George Jamesone, and

the most probable authority puts him down as the grandson of that

eminent artist, the son of Jamesone's (natural?) daughter Mary, who was

thrice married. Different authors, including Pinkerton, Chambers, and

Walpole-Dallaway, mention three different names and conflicting degrees

of relationship. The first of these speaks of" Alexander, the scholar of

Jamesone, who married that artist's daughter, and Cosmo Alexander, who

engraved a portrait of Jamesone, his great- grandfather, in 1728," and

regrets the absence of more information regarding the elder Alexander as

unknown to Walpole. Chambers refers to the same portrait engraving in

the anecdotes as by "Alexander Jamesone, a descendant of the painter;"

to another descendant of the same name—an engraver in the early part of

the eighteenth century; and also to a John Alexander, still another

descendant, who returned from his studies in Italy in 1720, and became a

painter of portraits of Mary Queen of Scots. Dallaway, differing from

these, referring to Jamesone, speaks of "Alexander his scholar, and who

married his daughter;" and also of "John Alexander, a lineal descendant

from Jarnisone, who was educated in Italy, and upon his return to

Scotland painted several historical pictures at Gordon Castle, and

delighted to copy (or invent) portraits of Mary Queen of Scots." By

putting the various dates in order, facts point only to one artist of

that name and the relationship already mentioned. Jamesone was married

before 1623, prior to which his natural daughter may or may not have

been born. John Alexander in 1718 was known to have been practising the

arts of engraving and painting in Italy, being among the earliest of the

Scottish artists who went abroad for that purpose, and spent a

considerable portion of his time at the Court of Cosmo de Medici at

Florence, to whom he dedicated a series of six etched engravings from

the old masters, of not very high excellence. On his return to Scotland

he enjoyed a considerable reputation as a portrait-painter, and was

employed at Gordon Castle by the duchess, who was daughter to the Earl

of Peterborough: a letter was printed in 1721 describing a staircase

there painted with the Rape of Proserpine by Mr John Alexander. The

engraved portrait of Jamesone in Walpole's 'Anecdotes' appeared

originally in 1728, the inscription on which, "George Jameson, Pinxit

anno 1623; Alexr. pronepos fecit Aqua forte A.D. 1728," has given rise

to the idea that "Alexr" was the Christian name only of the engraver; [The

scarce print of the painter with his wife and child, inscribed fully "Georgius

Jameson Scotus Abredonensio Patria Sue Apelles, eiusque uxor Isabella

Tosh et Filius. Geo. Jameson Pinxit Anno 1623; Alexr. pronepos fecit

Aqua forte, A.D. 1728."] and in the following year, 1729, "John

Alexander" appears in the list of members of the short-lived Academy of

St Luke in Edinburgh. Some years later he is known to have been in

practice in Edinburgh, as James Ferguson the astronomer, prior to 1738,

took a letter of introduction "from the Lord Pitsligo to Mr John Alex-

ander, a painter in Edinburgh, who allowed me to pass an hour every day

at his house to copy from his drawings," with the view to becoming an

artist. His death has been put down approximately at 1760, one of his

latest works being a portrait of George Murdoch, signed "Alexander

Pingebat, 1757." As to the Christian name Cosmo, it is likely to have

been adopted or given to him on his return from the Court of Duke Cosmo,

much in the same way as we speak of Chinese Gordon. On as slight a

foundation as this cognomen rests, another Alexander might be added to

the list, as one catalogue contains his Christian name as Pingebat.

There are four of Alexander's portraits in the Trinity Hall of Aberdeen,

consisting of the Rev. J. Osborn (1716-1748), Rev. John Moir, Thomas

Mitchell (Provost from 1698 till 1704), and Mrs Jane Mercer or Mitchell,

supposed to have been painted about 1737. It is said that at the latter

end of his life he commenced a picture of the escape of Queen Mary from

Lochleven Castle, which he did not live to finish. His portraits are no

doubt very numerous, but they are mainly of interest as marking an era

in the history of Scottish art. To this painter's brush, in emulation

with that of the younger Medina, we owe many of the genuine and

authentic portraits of Queen Mary, who has probably suffered more from

the pencils of the artists than from the axe of the executioner.

The

most important Scottish painter whose life began in the seventeenth

century was William Aikman, whose talents and virtues were celebrated by

more than one distinguished poet. He was a native of Forfarshire, the

son of William Aikman of Cairney, who married Margaret, third sister of

the first Sir John Clerk of Penicuik. He was thus nephew to Sir John

Clerk and Sir David Forbes of Newhall, and cousin to Baron Clerk and Mr

Forbes. It was through this connection that the poet Ramsay was

introduced to his friendship in Edinburgh. His patron, while attending

his duties in Parliament, introduced Thomson to his attention in London,

and through the latter he became acquainted with Mallet.

On the death

of his father he became at an early age laird of the ancestral estate of

Cairney near Arbroath, where he was born on the 24th October 1682.

Having early developed a strong love for the poetry of his native land,

and being also possessed by a strong desire to cultivate the study of

the sister art of painting, on reaching the age of twenty-four he sold

off the paternal estate in order that he might have the means of

carrying out his desire. His father, with a view to his son following

his own profession, had given him a good education; but young William no

sooner found himself master of his own actions, and with a pocket full

of money, than he set out for Rome in 1707 to pursue the study of art,

which it is said he had already begun under Sir John Aledina. The

proceeds of the broad acres of Cairney enabled him to study under the

best Roman artists for about three years, when he made a visit to

Constantinople and Syria, and after further improving himself in Italy,

returned to his native country in 1712. He settled down in Edinburgh for

ten or eleven years, in the course of which he married Marion, daughter

of Mr Lawson the publisher, of Cairnsmuir, by whom he had an only son

John, who died in early youth. His abilities were soon recognised, and,

with his family connections, led to his intimacy with many of the

notabilities of Edinburgh—such as Ramsay and John Duke of Argyll.

Although he succeeded to the practice of Sir John Medina, he did not

find the employment of a sufficiently remunerative kind, and on the

advice of the Duke of Argyll, removed to London in 1723, where he soon

found his way into the brilliant circle then breaking up, which gave

lustre to the reign of Queen Anne. Among his associates in London were

Swift, Pope, Gay, Arbuthnot, the Earl of Burlington, of architectural

taste, and Sir Robert Walpole (to whom among others he introduced the

poet of the 'Seasons,' who had come to London a literary adventurer).

Among others was Sir Godfrey Kneller, of similar taste and disposition

to himself, to whose works Aikman's bear a strong resemblance, somewhat

apart from what later became the character of the Scottish art. In

London he executed many commissions for prominent individuals and

families, notably the Earl of Buckingham for his seat at Blickling in

Norfolk. By the Earl of Burlington he was commissioned to paint a large

group of the royal family, including the king; but death arrested the

hand of the artist before putting in the portrait of the "boetry and

bainting" hating monarch. This picture, by an alliance with the

Burlington family, passed into the possession of the ducal house of

Devonshire.

Many of his earlier works are in Scotland, several being

in the galleries of the Dukes of Argyll and Hamilton. In the museum of

the Scottish Antiquaries hangs his portrait of Patrick, created first

Earl of Marchmont the year after being appointed Lord Chancellor of

Scotland, and who in 1684 was in hiding in the family vaults of Polwarth

church, where his daughter, the celebrated Lady Grizel Baillie, then at

the age of twelve, supplied him with food. At Amisfield House were

portraits of Sir Francis Kinloch and the Earl of Wemyss. His portrait of

himself is said to be in the gallery of painters at Florence, and

another, also of himself, Kneller-looking and carefully executed, hangs

in the Scottish National Gallery, the latter having been engraved in the

'Bee, or Literary Weekly Intelligencer.' [A

bust-portrait of Lady Hyndford in a blue dress was sold in the Gibson-

Craig collection in 1887 for £57, 15s.]

During his lifetime he

received an elegant tribute from the poet Boyse, and also from

Somerville, whom he painted. His death, which occurred in Leicester

Square on the 14th January 1731, was bewailed by his friends Thomson and

Mallet, the latter being the author of the following epitaph, long since

obliterated from the monument over his grave in the Greyfriars

churchyard in Edinburgh:-

Dear to the good and wise,

dispraised by none,

Here sleep in peace the father and the son.

By virtue as by nature close allied,

The painter's genius, but

without his pride.

Worth unambitious, wit afraid to shine,

Honour's clear light, and friendship's warmth divine.

The son, fair

rising, knew too short a date

But oh, how more severe the parent's

fate!

He saw him torn untimely from his side,

Felt all a

father's anguish,—wept and died."

The modest enthusiast in art, John

Smibert, a friend of the author of the' Gentle Shepherd,' and a native

of Edinburgh, whose life links the seventeenth with the following

century, was an artist of some note in his day. He was born in 1684, two

years later than Aikman, in the Grassmarket, and was the son of a dyer.

After serving an apprenticeship as a common house-painter in Edinburgh,

he gradually wrought his way against the usual obstacles which a poor

artist must always encounter, and ventured to London, where for bare

subsistence he turned his hand to coach - painting. Devoting his time

afterwards to study, and painting for that much-maligned but very useful

class of people known as picture-dealers, he managed to spend three

years in Italy copying from the old masters. While in Italy he made the

acquaintance of the famous Dean Berkeley, subsequently Bishop of Cloyne;

and at Florence painted a picture of Siberian Tartars for the Grand Duke

of Tuscany, which that noble presented to the Russian Czar. He was so

far benefited by his study in Italy, that on his return to London he was

able to command a very fair practice as a portrait-painter. This was

probably about 1721 or 1722, as Allan Ramsay's poetical epistle "To a

Friend at Florence" seems to have been addressed to Smibert about that

date. He drew the portrait of Ramsay which was prefixed to his second

quarto volume, published in 1728: possibly this is the same which is

still in the Newhall House collection, and stated to be the original

family portrait.' After having by his ardour and perseverance surmounted

the asperities of his fortune, he was tempted to embark in a curious and

quixotic scheme, much against the persuasion and advice of his friends.

Dean Berkeley, whose benevolent heart was set upon civilising the

foreign heathen, conceived the idea of instituting a university or

college of science and art in the Bermudas, in which the children of the

natives were to be trained and indoctrinated in Christian duties, civil

knowledge, and the fine arts. The scheme, which was favoured and

encouraged by the king, and as a matter of course by many of his

courtiers, was joined by Smibert, who, along with Dean Berkeley, left

England in 1728, in the visionary expectation of passing a useful,

happy, and tranquil life in an ideal climate. The death of the king,

however, and consequent cooling of the ardour of those who imitated him

in the usual courtly manner, brought the scheme to a premature end, and

Smibert, being probably acquainted with this on his arrival in America,

proceeded no farther. Along with the Dean, he remained about two years

at Newport in Rhode Island, where he painted a large picture of Berkeley

with his family, including a portrait of himgelf: this picture is said

to be preserved at Yale College, where it is prized as being the first

picture group of figures painted in the New World. The "civilising

scheme" was finally abandoned at Boston, where he was more fortunate

than he would have been successful if he had reached his original

destination, as he married the daughter of Dr Williams, the Latin master

of Boston School, of considerable fortune, whom, in March 1751, he left

a widow with two children. His son Nathaniel gave promise of

considerable ability as an artist, but died too young to achieve a

reputation.' Smibert's name is chronicled as one of the pioneers of art

in America.

Another Scottish artist contemporaneous with Smibert,

practising in England, is mentioned by Vertue, but no relative

circumstances of him are recorded beyond the bare fact that he was born

in Leith in 1682, and known as Alexander Nesbitt.

In the list of

subscribers to the edition of Allan Ramsay's poems which was published

in 1721, as well as elsewhere, there appears beside the name of Smibert

that of James Norrie, known as "old Norrie," who was probably the first

to create, or at least to minister to, the taste for landscape-painting

in the Scottish metropolis. There were several generations of the same

family carrying on business as house painters and decorators in

Edinburgh. Their shop, which was near Allan Ramsay's in the High Street,

was only closed about 1850; and the last of them in the business, a

great chum of J. F. Williams and of the Waverley Club coterie, had a

shop in Register Street. A large portion of their business was landscape

decorations, a form of art then very fashionable in and about Edinburgh,

more especially applied to the mantelpieces of private dwellings; and

from their workshop emanated more than one distinguished artist, not the

least of whom was Alexander Runciman. An interesting house in Riddle's

Close, originally the residence of Sir John Smith of Grotham, Provost of

Edinburgh, is mentioned by Dr Wilson, the second flat of which was in

his time occupied as a binder's workshop. One of the apartments, bearing

the date 1678 on the stuccoed roof, had wooden panelled walls decorated

in a rich style by Norrie; on every panel, including those of the

shutters and doors, was a different landscape, sometimes executed with

great spirit; even the keystone of an arched recess had a mask painted

on it: and the Doctor describes the whole as being singularly beautiful,

notwithstanding the injury which many of the paintings had sustained.

The Norries, "old Norrie" and his son James, also painted a few

landscape-pictures, apart from being merely applied to wall decoration,

as the New- hail catalogue mentions two views by J. Norrie, one of them

dated 1731. The Royal Scottish Academy possesses a portrait of the first

of the name in the business. Among other landscape- painters of about

this period there is mention of a "Cheap Cooper"; but their works, if

preserved at all, are scarce to be met with, and difficult to identify.

Reference has already been made to the destruction, often wanton or

inconsiderate, of many specimens of old art in Scotland; and while these

lines are being written, notice is given of the demolition of the old

patrician mansion known as Milton House in the Canongate of Edinburgh,

to make way for a Board School. Although in no ways very valuable as a

piece of architecture, being built in the somewhat heavy style common to

the early part of the last century, it contains some interesting

decorations of the painter's art of that period. The walls of the

drawing- room, wherein Hanoverian and Jacobite courtiers had formerly

assembled, are decorated by a series of landscape and allegorical

subjects, enclosed by rich borders of fruit and flowers, executed with

great spirit, and still fresh and bright in colour. Interspersed among

the ornamental borders are various grotesque figures, having the

appearance of being copied from a fourteenth-century illuminated missal.

These represent a cardinal, monk, priest, and other churchmen, painted

with considerable humour, and differ so much from the general character

of the composition, that it was probably a whim of Lord Milton, which

the artist managed to humour without detracting from the harmony of the

design. It is possible that old Norrie had something to do with these.

Dr Daniel Wilson, on supposition, has ascribed them to Zuccarelli, who

had a reputation for such work at that time in England. Patrick Gibson,

the artist, in 1816 mentions tfiem as the work of Delacour, who was the

first master of the Trustees' Academy, appointed in 1760; but these are

mere guesses. Along with these may be mentioned some fragments of

paintings of an unusual character for a sacred edifice, which were

discovered on the demolition of one of the chapels on the restoration of

St Giles's in Edinburgh in 1829. These appear to have been painted on

the panelling of the chamber about the period of the Revolution, when it

formed an appendage to the Council Chambers, and represent a trumpeter,

a soldier bearing a banner, and a female figure holding a cornucopia, in

the costume of William III. They passed into the collection of the late

C. K. Sharpe, and are described as being over half the size of life and

really works of some merit.

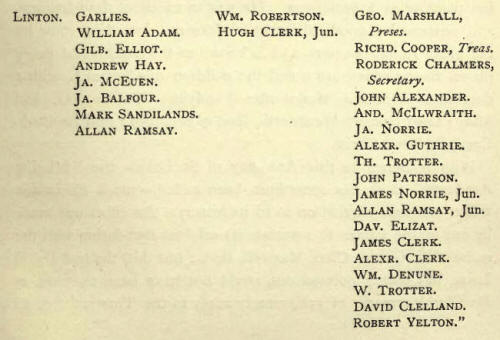

So early as the year 1729, there are

traces of an association, doubtless the first of the kind in Scotland,

in Edinburgh, bearing the somewhat pretentious title of the Academy of

St Luke, which seems to have been composed of the few artists and lovers

of art then in the Scottish metropolis, and remarkable as including in

its list of artist members the name of Allan Ramsay, junior, who would

then be in his sixteenth or seventeenth year. The following is a copy of

the indenture [Patrick Gibson, Ed. Ann. Reg., 1816.

The indenture afterwards passed into the collection of the late David

Laing, and is now in the R.S.A.] :

"At Edinburgh, the

eighteenth day of October, A. Dom. MDCCXXIX.

"We, Subscribers,

Painters, and Lovers of Painting, Fellowes of the Edinburgh School of St

Luke, for the encouragement of these excelent arts of Painting,

Scuijiture, Architecture, &ct., and Improvement of the Students Have

agreed to erect a publict Academy, whereinto every one that inclines, on

aplication to our Director and Council, shal be admited on paying a smal

sum for defraying Charges of Figure and Lights, &ct. For further

encouragement, some of our Members who have a Fine Colection of Models

in Plaister from the best Antique Statues, are to lend the use of them

to the Academy.

"To prevent all disorder, the present Members have

unanimously agreed on the observation of the Folowing Rules

"I. To

meet anualy on the eighteenth day of October, being the Feast of St Luke

our Patron, to chuse a Director, Treasurer, and Secretary, and four

common Councillours, for the ensuing Year, of which Council of Seven

ther shal ever be four Mr Painters. This sd. Council to be chosen

yearly, and mayor not he rechosen, but upon no account to continoue

above two Years at a Time.

"II. That the Seclerunts of the Society be

Registrated in a Book to be kept by the Secretary for the time being.

III. The Academy to meet on the first of November Jajvij and twenty-nine

years, and to continoue till the last of February, four times

a-week—viz., on Mundays, Tusdays, Thursdays, and Fridays—at five o'clock

at night, and to draw the space of two hours. To meet again on the first

of June, and continoue till the last of July, on the for said days of

the week ; but the two Drawing hours to be in the morning from six to

eight. The Summer Season being chiefly design'd for Drawing from Antique

Models and Drawghts of the best Masters of Foraigne Schools by a Sky

Light; for which Purpose, a large Portfolie to be kept in the Academy

for preserving all curious Drawings already given, or that may be given

for that end.

IV. On Placing of every new Figure, those present to

draw Lots for the choise of their Seats.

"V. That every Member

acorcling to His Seniority shal be allowed in His turn to place or put

the Figure in what ever Posture He pleases, or have it in His power to

depute annother to do it for Him, and to have the first choise of His

Seat.

"VI. All Noblemen, Gentlemen, Patrons, Painters, and lovers of

Painting, who shal contribute to carrying on the Designe, (if they do

not incline to draw Themselves) shal have the Privilege by awritten

Order to our Director, to assign His Right to any Young Artist whom He

is Pleased to Patronise.

The Academy thus constituted contained eleven honorary and eighteen

artist members, and its title and rules were evidently suggested by

those of the Academy of St Luke at Rome, where one or two of the members

had studied. With regard to this list, John Alexander and the Norries

have already been mentioned, and Ramsay remains to be noticed further

on. George Marshall, the Preses, who died in 1732, was a painter of

still-life and portraits, and is said to have studied under Knelier in

London and also in Rome, having previously acquired the rudiments of his

art from Scougal. Roderick Chalmers also practised portrait-painting,

and has left a picture, in the hail of the Incorporated Trades of

Edinburgh, in which are introduced portraits of the various deacons

working at their different crafts or "essays." Far more important than

these, however, was Richard Cooper, the engraver, who did more for the

cultivation of art in Scotland than has hitherto been acknowledged, and

in whose studio the celebrated Sir Robert Strange learned his art before

going to France. Cooper was most probably of English birth, although

Edinburgh sometimes claims the credit of that event, and was at first,

it is believed, a drawing- master, after which he studied art at Rome

with a view to following painting as a profession. He was an excellent

draughtsman, and possessed a good collection of drawings, including some

by the great Italian masters, and is known as the engraver of many

plates, among which are noted the children of Charles I., with a dog,

and Henrietta Maria after Vandyke; William III. and Mary; Lord Bacon;

Wentworth, Earl of Strafford; and Annibale Caracci's Dead Christ.

With

reference to this Academy of St Luke,—the "Missing Academy," as it has

sometimes been called,—much discussion was at one time carried on as to

its history. An effort was made by one of the Clerks to associate its

original foundation with the name of Sir George Clerk-Maxwell, Bart.;

but this, the late David Laing has clearly pointed out, could not have

been the case, as Mr Clerk's remarks of 1784 simply apply to the

Trustees' School of Drawing, commenced in 1760. Dr Laing, however,

evidently made a mistake when he identified this Academy with that

attended by Strange, on the authority of the memoirs of the latter. In

the memoirs of the engraver it is clearly stated, that with a view to

fostering his own art, as well as cultivating drawing and painting,

Cooper in 1735 was instrumental in encouraging the opening of a Winter's

Academy, "at the modest subscription of half-a-guinea." It has to be

noted that the St Luke's Academy was not projected merely as a "Winter"

one; and besides, from the importance and number of the names on its

list, it is not likely that Strange would have omitted to give it its

proper title if it had existed for six years. In the Winter's Academy

certainly, and probably in the St Luke's, Cooper gave his

superintendence and the use of his portfolios. The latest mention of the

ambitious Academy of St Luke occurs in June 1731, when a room in the

University was granted for its use, soon after which it seems to have

expired.