|

With notices of some of

the uses to which they were put by the old Highlanders, and the

superstitions connected with them.

He said—The subject of

the Gaelic names of the trees and plants that grow around us is a very

important and interesting one, but uufortunately, I must say, a very

much neglected one by the present race of Highlanders. Our ancestors had

a Gaelic name, not only for all the trees and plants that grew in their

own country, but also for many foreign plants. Yet there are very few of

the present generation who know anything at all about those Gaelic

names, except perhaps a few of the very common ones, such as Darach,

tieithe, Giuthas, Calltuinn, &c.

The principal reason for

this is, that the Highlanders of the present day have not to pay so much

attention to, or depend so much upon, the plants of their own country as

their ancestors did who depended almost entirely on their own vegetable

substances for then1 medicinal, manufacturing, and other purposes. A

great many of those Gaelic names are already lost, and many more will be

so in a few years if some steps are not taken to preserve them, for

though, certainly, wo have many of them already in print, scattered

through such works as Alex. M‘Donald’s (Mac Mhaighstir Alastair)

Vocabulary, Liglitfoot’s Flora Scotica, the Gaelic Bible, and the

Dictionaries, yet the great majority of the Gaelic names are not in

print, but only preserved amongst the old peoplo, and will soon be

forgotten unless speedily collected. So far as I am aware there is not

yet a single work on this important subject; therefore I have chosen it

as the subject of the following paper, in which I will give the Gaelic

name, and a short account of the various uses to which our ancestors put

each, beginning with a few of our common trees and going down to the

smaller plants, trusting it will awaken an interest in the subject, and

be the beginning of an effort to collect all the Gaelic names possible

ere it be too late. In studying the Gaelic names of plants, even the

most careless observer cannot fail being struck with the fine taste and

the intimate acquaintance with the various peculiarities and different

properties of plants, displayed by our ancestors in giving the Gaelic

names to plants. This I think is one of the strongest proofs we have

that our ancestors were keen observers of nature—an advanced and

cultivated race—and not the rude savages which some people delight to

represent them. In reading the works of our best Gaelic bards, from

Ossian downwards, we cannot help also being struck with their

acquaintance with the names and various peculiarities of plants. Take

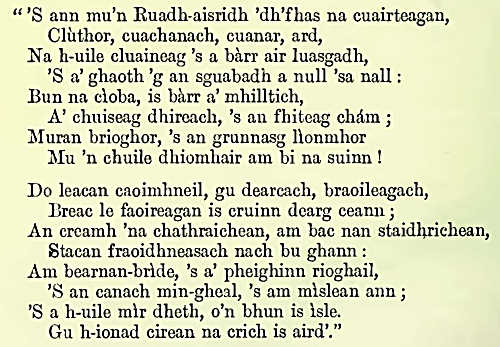

M'lntyre’s description of Coire- Gheathaich:—

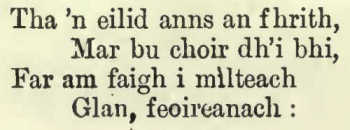

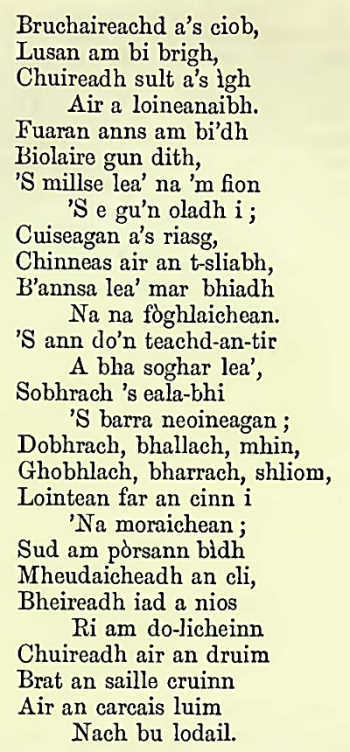

Again, in his Moladh

Beinn-Dorain, we have—

Without further remarks

in the way of introduction, I will proceed with giving you an account of

some of our Highland Trees, Shrubs, and Plants.

Alder.—Latin,

Alnus Glutinosa — Gaelic, Fearna.—This well-known tree is a native of

the Highlands, where it grows to perfection all over the country by the

side of streams, and in wet marshy places. It seems in former times to

have grown even more abundantly, and that in places where now not a tree

of this or any other kind is to be found. This is proved by the many

names of places derived from this tree, such as Glen Fernate—Gleann

Fearn-aite—in Athole ; Fearnan in Breadalbane; Fearn in Ross-shire;

Fernaig in Lochalsh, &c. In a suitable situation the alder will grow to

a great size. There is mention made in the account of the parish of

Kenmore, in the “ New Statistical Account of Scotland”, of an alder tree

growing in the park of Taymouth Castle, the circumference of which, in

1844, was 12 feet 8 inches. The wood of this tree resembles mahogany so

much that it is generally known as “ Scotch Mahogany.” It is very red

and rather brittle, but very durable, especially under water. Lightfoot,

the learned author of the “ Flora Scotica,” mentions that, when he

accompanied Pennant on his famous “ Tour” in 1772, the Highlanders then

used alder very much for making chairs and other articles of furniture,

which were very handsome and of the colour of mahogany. He mentions that

it was much used by them for carving into bowls, spoons, &c., and also

for the very curious use of making heels for women’s shoes. It was once

very much used, and in some parts of the Highlands it is still commonly

used, for dyeing a beautiful black colour. By boiling the bark or young

twigs with copperas it gives a very durable colour, and supplies the

black stripes in homemade tartan. A decoction of the leaves was counted

an excellent remedy for burnings and inflammations, and the fresh leaves

laid upon swellings are said to dissolve them and stay the inflammation.

The old Highlanders used to put fresh alder leaves to the soles of their

feet when they were much fatigued with long journeys or in hot weather,

as they allayed the heat and refreshed them very much. Our ancestors

were sharp enough to discover the curious fact that the alder wood

splits best from the root, whereas all other trees split best from the

top, which gave rise to the old Gaelic saying, “ Gach fiodh o na bliarr,

’s an fhearna o’ na bhun.”

Apple and Crab Apple.—Latin,

Pyrus Mdlus—Gaelic, Ubhal, Ubhal-fiarthatch.—The crab apple is a native

of the Highlands, where it grows in woods and by riversides, to a height

of about 20 feet. Of course the cultivated apple of gardens and orchards

is just an improved variety of the same, which by ages of care and

cultivation has been brought to its present perfection. The fruit of the

crab is small and very bitter, but its juice is much used for rubbing to

sprains, cramps, See., and the bark is used by the Highlanders for dying

wool of a light yellowish colour. The apple was cultivated at a very

early date in Britain, as it is often mentioned by our earliest writers.

Logan says that from a passage in Ossian it is clear that the ancient

Highlanders were well acquainted with the apple. Pliny says that the

apple trees of Britain bore excellent fruit, and Solinus writes that

Moray and the north-eastern part of Scotland abounded with apples in the

third century. Buchanan says that Moray, which of course in his daj

included Invemess-shire, surpassed all the other parts of Scotland for

excellent fruit trees. The monks paid great attention to the cultivation

of the apple, and they always had gardens and orchards attached to their

monasteries, near the ruins of which some very old apple trees are still

found growing and bearing good crops of fruit, for instance, the old

apple tree a few yards north from Beauly Priory. We read that the monks

of Iona had very fine orchards in the ninth century, but they wore

destroyed and the trees cut down by the Norwegian invaders. King David

I., about 1140, spent much of his spare time in training and grafting

fruit trees. It is a very great mistake indeed that the apple is not

cultivated more now in the Highlands, for from the suitable soil in many

places, and also from the great shelter afforded by the hills and woods,

in many of the glens and straths, it would grow to perfection where at

present there is not a single tree. Indeed it is entirely neglected

except in gentlemen’s gardens. The present Highlanders have not such a

high opinion of the apple as Solomon had—“ Mar chrann-ubhall am measg

chrann ua coille, is amhuill mo rimsa am measg nan 6ganach; fo sgkile

mhainnaich mi, agus shuidh mi sios ngus bha a tlioradh milis do m’ bhlas

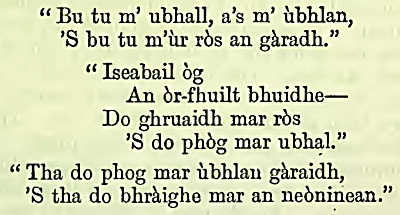

” (Song of Solomon iij 3). Almost all the Gaelic bards in singing the

praises of their lady-loves compare them to the sweetsmelling apple:—

The well-known fact that

the largest and finest apples always grow on the young wood at the top

of the tree gave rise to the old Gaelic proverb—“ Bithidh ’n t-ubhal is

fearr, air a mheangan Is airde.” The crab apple is the badge of the Clan

Lamond.

Apricote.—Latin,

Armeniaca Vulgaris—Gaelic, Apricoc.--The apricote is a native of the

Levant, but was introduced into Britain in 1548. This excellent fruit,

which was once much grown by the monks, is very seldom to be found now

in the Highlands, though common enough in gardens in the Lowlands of

Scotland. Alexander M'Donald (Mac Mhaighstir Alastair) mentions it in

his Gaelic list of fruit trees, and Logan, in his “ Scottish Gael,” says

that it thrives very well as far north as Dunrobin. By giving it the

shelter of a wall facing the south, it will thrive and ripen its fruit

in most of the low straths of the Highlands.

Ash.—Latin,

Fraxinus Excelsior—Gaelic, Uinnseann.—The ash is a native of the

Highlands, where, in a suitable situation, it will grow to a height of

nearly 100 feet. This useful tree, so well-known to everybody, is noted

for its smooth silvery Lark when young, and for its graceful fern-like

leaves, which come out late in spring, and are the first to fall in

autumn, and of which horses and sheep are very fond. The ash will adapt

itself to any situation, and will flourish according to the richness of

the soil, and the amount of shelter it receives, wherever it happens to

spring up, from a seed carried by the wind or by birds. We have it in

the Highlands in every stage—from the stunted bush of a few feet high,

which grows in the clift of some high rock, or by the side of some bum

high up amongst the hills, to the noble tree of a hundred feet high,

which glows in our straths, and of which I may give the following

example from my native district of Athole. It is described by the Rev.

Thos. Buchanan in his account of the parish of Logierait, in “ the New

Statistical Account of Scotland ” (1844). He says— “ There is a

remarkable ash tree in the innkeeper’s garden, near the village of

Logierait. It measures at the ground 53£ feet in circumference ; at

three feet from the ground 40 feet; and at eleven feet from the ground,

22 feet. The height is 60 feet; but the upper part of the stem appears

to have been carried away. The height is said to have been at one time

nearly 90 feet. The trunk is hollow from the base, and can contain a

large party. This venerable stem is surmounted by a profusion of

foliage, which, even at the advanced age of the tree, attracts the eye

at a distance to its uncommon proportions. An old man of the age of one

hundred is at present in the habit of taking his seat daily within the

hollow formed by its three surviving sides—no unsuitable companion to

the venerable relic.” In the same work, in the accounts of the parishes

of Kenmore and "Weem, mention is made of an ash in the park of Taymouth

Castle, 18 feet in circumference, and other two on the lawn at Castle

Menzies, 16 feet. The wood of the ash, which is hard and very tough, was

much used by the old Highlanders for making agricultural implements,

handles for axes, &c. Besides those peaceful uses to which they put the

ash, they also used it for warlike purposes, by making bows of it when

yew could not be had, and also for making handles for their spears and

long Lochaber axes. The Highlanders have many curious old superstitions

about the ash, one of which is also common in some parts of the

Lowlands, viz. :—That the oak and the ash fortell whether it is to be a

wet or a dry season, by whichever of them comes first into leaf,—if the

ash comes first into leaf, it is to be a very wet summer; but very dry

if the oak comes first. Another curious old superstition is still

lingering in some parts of the Highlands about the virtue of the sap for

newly-born children, and as Lightfoot mentions it as common in the

Highlands and Islands when he travelled there with Pennant, in 1772, I

may give it in his words. He says:—“ In many parts of the Highlands, at

the birth of a child, the nurse or midwife, from what motive I know not,

puts the end of a green stick of ash into the fire, and, while it is

burning, receives into a spoon the sap or juice which oozes out at the

other end, and administers this as the first spoonful of liquors to the

new-born babe.” Another old Highland belief is that a decoction of the

tender tops or leaves of the ash taken inwardly, and rubbed outwardly to

the wound, is a certain cure for the bite of an adder or serpent, and

that an adder has such an antipathy to the ash that if it is encompassed

with ash leaves and twigs, it will rather go through fire than through

the ash.

“Theid an nathair troirnh

an teine dhearg,

Mu’n teid i troimh dhuilleach an iiinnsinn.”

In fact, the adders were

supposed to regard the ash amongst the forest trees as they did the

M'lvors amongst the Highland clans! Every Highlander knows the old

saying about the M‘Ivors and the adders—

As a proof of the many

uses to which the wood of the ash may be put, I may quote Isaiah xliv.

14—“ Suidhichidh e crann-uinsinn, agus altruimidh an t’ uisge e. An sinn

bithidh e aig duine chum a losgadh; agus gabhaidh e dheth, agus garaidh

se e fein : seadh cuiridh e teine ris, agus deasaichidh e aran. Cuid

dheth loidgidh e ’san teine, le cuid eile dheth deasaichidh agus ithidh

e feoil; r6s-taidh e biadh agus sasuichear e : an sin garaidh se a fein

aguo their e—Aha rinn mi mo gharadh, dh’ aithnich mi an teine. Agus do

’n chuid eile dheth ni e dla eadhon dealbh snaidhte dha fein; crom-aidh

e sios dha agus bheir e aoradh dha; agus ni e urnuigh ris agus their e—Teasairg

mi, oir is tu mo dhia.” The ash is the badge of the Clan Menzies.

Aspen.—Latin,

Populus Tremula—Gaelic, Critheann.—The aspen, which grows to a height of

about fifty feet, is a native of the Highlands, where it grows in great

abundance all over the country, in moist places or on the banks of

streams. It is very rapid in the growth, consequently its wood is not of

much value, being very soft, but white and smooth. This wood was much

used by the Highlanders for making pack-saddles, wood cans, milk pails,

&c. The great peculiarity about the aspen, and which has made it the

object of many curious old superstitions, is the ever trembling motion

of its leaves, which gave rise to its Gaelic name, “Critheann,” or “

trembling.” The cause of this is that leaves which are round or slightly

heart-shaped, have veiy long slender stalks, so that they quiver and

shake with every breath of wind, and the leaves being hard and dry, give

a peculiar rustling sound. There is a common belief among the

Highlanders that the Saviour’s cross was made of the wood of the aspen,

and that ever since then the leaves of this tree cannot rest, but are

for ever trembling! In the Bible, wherever we find the poplar mentioned

in the English, it is always translated Critheann or Crithich in Gaelic,

as in Genesis xxx. 27, and Hosea iv. 13. As the aspen is a variety of

the poplar, it may be correct enough to translate poplar “ critheann,”

but Alex. M‘Donald (Mac Mhaimstir Alastair), gives us another name for

the poplar, Cmnn Poblmill.

Bay, or Laurel Bay.—Latin,

Laxrus noblis—Gaelic, Laiblireas. —This beautiful evergreen tree, the

emblem of victory amongst the ancients, is a native of Italy, but was

introduced into Britain in 1561. It would likely be some time after that

however, before it was much planted in the Highlands, where it grows and

thrives very well now in all the low straths and glens. Laibhreas is the

Gaelic name I have found for it in over a dozen different books, but in

the Bible, where it is only once mentioned (Psalms xxxvii. 35), it is

translated Ur-chraobh-uaine. There are a great many old superstitions

connected with the bay, only one of which I will give in the words of an

old writer—“ that neither witch nor devil, thunder nor lightning, will

hurt a man where a bay tree is ! ” If such be the case it is truly a

valuable tree. The laurel bay is the badge of the Clan MfLaren, and from

it they take the motto which they bear above their crest—“ Bi se Mac an

V slaurie,” meaning that they are the sons of victory, of which the

laurel is the emblem.

Beech.—Latin, Fa

jus Sylvatica—Gaelic, Faidh-bhile.—This tall and graceful tree needs no

description, as it is well-known to everybody. It is a native of the

Highlands, and grows to a height of about eighty feet. It is a very

hardy tree, an I grows in the glens all over the Highlands, where in

favourable situations it attains an immense size. Very large beech trees

are found at Dunkeld and in the pass of Kiliiecrankie, where, to judge

from their size, some of those beeches probably afforded shelter to many

a wounded soldier on the 17th July, 1689, when “Bonnie Dundee” fought

and fell on the field of Raonruarie. Mention is also made in the New

Statistical Account of two beech trees at Castle Menzies, one 17 and the

other 19 feet in circumference, also one at Taymouth Castle, 22 feet. Of

the beech an old writer says:—“ The mast or seeds of this tree will

yield a good oil for lamps; they are a food for mice and squirrels, and

swine are very fond of them, but the fat of those which feed on them is

soft and boils away, unless hardened before they are killed by other

food. The wood is brittle, very fissile, durable under water, but not in

the open air. It is the best of all woods for fuel, and it is sometimes

used for making axles, bowls, sword scabbards,” &c. As the leaves of the

beech are very cooling, they were used by the Highlanders as a poultice,

to be applied to any swellings to lessen and allay the heat. They were

also used in some parts when dry for stuffing mattresses instead of

straw, to which they are much superior for that purpose, as they will

continue fresh for many years, and not get musty and hard as straw does.

Black Beech.—Latin,

Fagus sylvatica atro-rubens—Gaelic, Faidh-bhile dubh.—This sombre and

moumful-looking tree is just a variety of the common beech, and has

mostly the same nature, only that it does not grow quite so tall. The

black beech is to be found™with foliage of every shade, from a

brownish-green to a blood-red, and almost even to jet black—the two

latter forming a very fine contrast to the light green of the common

beech, or the white flowers of the hawthorn or the mountain ash, and is

therefore a very striking object in a landscape. There are some very

large trees of this kind in the Highlands, such as at Guisachan, in

Strathglass, where they have a very rich dark colour.

Birch.—Latin,

Betula alba—Gaelic, Beithe.-—I need not say that the birch is a native

of the Highlands, where it is the most common of all our forest trees,

and its graceful habit adds to the beauty of almost every glen and

strath in the land of the Gael. It is still much used in many ways, but

was much more so by the old Highlanders, who turned it into almost

endless uses. The wood was once much used by them for making arrows for

the men and spinning wheels for the women—both being articles once

indispensable in the Highlands, although now things of the past. The

wood is still much used in the Highlands by turners, as it is the best

possible wood for their work, and it is also much used for making

bobbins. As Lightfoot mentions many of the uses to which the Highlanders

put the birch, I may give them in his words :—“ Various are the

economical uses,” he says, “ of this tree. The Highlanders use the bark

to tan their leather and to make ropes. The outer rind, which they call

‘ Mhilleag,' they sometimes burn instead of candles. The inner bark,

before the invention of paper was used to write upon. The wood was

formerly used by the Highlanders for making their arrows, but is now

converted to better purposes, being used by the wheelwrights for

ploughs, carts, and most of the rustic implements ; by the turners for

trenchers, ladles, &c., the knotty excrescences affording a beautiful

veined wood; and by the cooper for hoops. The leaves are a fodder for

sheep and goats, and are used by the Highlanders for dyeing a yellow

colour. The catkins are a favourite food of small birds, especially the

sisken, and the pliant twigs are well known to answer the purposes of

cleanliness and correction / There is yet another use to which this tree

is applicable, and which I will beg leave strongly to recommend to my

Highland friends. The vernal sap is well known to have a saccharine

quality capable of making sugar, and a wholesome diuretic wine. This

tree is always at hand, and the method of making the wine is simple and

easy. I shall subjoin the receipt—‘ In the beginning of March when the

sap is rising, and before the leaves shoot out, bore holes in the bodies

of the larger trees and put fossets therein, made of elder sticks with

the pith taken out, and then put any vessels under to receive the

liquor. If the tree be large you may tap it in four or five places at a

time without hurting it, and thus from several trees you may gain

several gallons of juice in a day. If you have not enough in one day

bottle up close what you have till you get a sufficient quantity for

your purpose, but the sooner it is used the better. Boil the sap as long

as an}- scum rises, skimming it all the time. To every gallon of liquor

put four pounds of sugar, and boil it afterwards half-an-hour, skimming

it well; then put it into an open tub to cool, and when cold run it into

your cask ; when it has done working bung it up close, and keep it three

months. Then either bottle it off or draw it out of the cask after it is

a year old. This is a generous and agreeable liquor, and would be a

happy substitute in the room of the poisonous whisky.’ ” So says

Light-foot. Another writer says—“ In those parts of the Highlands of

Scotland where pine is not to be had, the birch is a timber for all

uses. The stronger stems are the rafters of the cabin, wattles of the

boughs are the walls and the doors, even the chests and boxes are of

this rude basket work. To the Highlander it forms his spade, his plough,

and if he have one, his cart, and his harness ; and when other materials

are used the cordage is still withies of twisted birch. These ropes are

far more durable than ropes of hemp, and the only preparation is to bark

the twig and twist it while green.”

Warty or Knotty Birch.—Latin,

Betula Verrucosa—Gaelic, Beithe Carraigeach, Beithe Dubh-chasach.—This

tree, though very much resembling the common birch, is quite a distinct

variety, and was always treated as such by the old Highlanders, which is

another strong proof of how keenly our ancestors studied nature, and how

quick they were to discover even the slightest peculiarity or difference

in the habit or nature of any tree or plant, and the nicety and taste

with which they gave the Gaelic name descriptive of any such

peculiarity. It is a native of the Highlands, where it generally grows

larger and stronger than the common birch. It was always used by the old

Highlanders for any particular work where extra strength or durability

was required. Owing to its dark bark and its gnarled and knotty stem it

is not such a graceful tree as the common birch, but the wood is of a

better quality.

Weeping Birch.—Latin,

BetulaPendula—Gaelic, Beithe Dubh-ach.—The weeping birch is the most

graceful and beautiful of all our native Highland trees, and where it

grows to perfection, as it does in Strathglass, Lochness-side, and in

many other parts of the Highlands, there is nothing that can add more to

the beauty of the landscape than its tall silvery stem, with its

graceful drooping branches which, though 20 or 30 feet long, are no

thicker than a common pack thread. Well might Coleridge call the weeping

birch—“The Lady of the Woods.”

Dwarf Birch.—Latin,

Betula Nana—Gaelic, Beithe Beag.—The dwarf birch, the hardiest of all

trees or shrubs, grows abundantly on some of the higher ranges in the

Highlands, though unknown south of the Highland border, or even in our

own low straths. It grows in Corry-challin, in Glenlyon, in Strathardle,

on Ben Lawers, Ben-y-gloe, and on several of the other Perthshire

Grampians, also in the wilds of Strathglass, and on the moors near Loch

Glass, in Ross-shire. It is of an erect habit, but seldom reaches a

height of over three feet. The bark is of a shining red or dark purple

colour, and the fertile catkins which grow at the extremity of the

branches are a favourite food of grouse and ptarmigan. As the leaves and

twigs of this variety yield a much brighter yellow dye than any of the

other varieties of birch, it used to be much sought'after by the

Highland housewives, and through their cutting it all when found growing

near their houses, it is now unknown in many places where it was once

common. Another, and perhaps a stronger reason for its disappearance is

that it never grows high enough to be beyond the reach of sheep, which

are now all over the country, and as they are very fond of the young

twigs and leaves, they constantly nip off the young wood, and so never

allow it to seed, and very soon kill the parent shrub itself. In the

Arctic regions the dwarf birch is found growing on the borders of the

eternal snow, where it is the only variety of tree known, and its

catkins and seeds afford the only food for the large flocks of ptarmigan

and other birds found in those high northern latitudes.

Birds’ Cherry.—Lntin,

Gerasus padus—Gaelic, Fiodhag.— This tree is a native of the Highlands,

where it grows on the banks of streams, and produces large crops of its

black berries. These berries are very sour, but birds are very fond of

them, which, of course, gave rise to its name. Lightfoot informs us that

the berries were used by way of infusion in brandy in the Highlands,

when he was there.

Black Thorn.—Latin,

Primus spinosa—Gaelic, Sgitheach dubh; Preets nan airneag.—This is a

well-known native shrub, and grows very common all over the country. The

bark was much used by our ancestors for dyeing a bright red colour.

Lightfoot mentions that the fruit will make a very fragrant and grateful

wine, a fact which the great botanist never forgets to mention of any

fruit or plant out of which it is possible to cxtract anything

drinkable!

Box.—Latin, Buxus

sempervirens—Gaelic, Bucaa.—The box is a native of England, but seems to

have been introduced very early into the Highlands, where it thrives

very well in the low glens. The wood, which is very hard and

close-grained, was used by the old Highlanders for carving ornamental

dirk and sgian dubh handles, cmchs, &c. From the great resemblance of

the box to the red whortleberry, or Lus nam Braoileag, the real badge of

the Clan Chattan, the box was often used by that Clan instead of the

whortleberry, as it was generally easier procured, which gave rise to

the mistaken idea that the box is the badge of the Clan Chattan.

Brier Rose.—Latin,

Rosa canina—Gaelic, Dris ; An fhearr-dhris ; Preas nam mucag.—This

prickly shrub grows all over the Highlands, where its fruit—mucagan—is

often eaten by children, and also sometimes used for preserves. The

strong prickles with which it is armed gave rise to the old Gaelic

proverb, “ Cho crosda ris an dris.” The Highlanders used the bark of the

brier, with copperas, for dyeing a beautiful black colour.

Broom.—Latin,

Spartium Scoparium—Gaelic, Bealaidh.—The “ bonny, bonny broom ” needs no

description, as it is known to everybody, and its bright green branches

and golden blossoms add to the beauty of most Highland landscapes. The

old Highlanders used the broom for almost endless purposes, some of

which I may mention here. The twigs and branches were used to thatch

houses and stacks, to make brooms, and to weave in their fences to

exclude sheep and hares from their gardens, and also to tan leather, for

which purpose it is equal to oak bark. A decoction of this shrub was

much recommended for the dropsy, and half an ounce of the flowers or

seeds was considered a strong vomit by the old Highland housewives.

During snow, sheep and deer are very fond of browsing on it, but if

sheep not accustomed to it are allowed too much of it at first it makes

them giddy, or as the shepherds say drunk. The broom is the badge of the

Clans Forbes and M‘Kay.

Cherry.—Latin,

Prunns Cerasus—Gaelic, Sfris or Sirist.—Of course this tree is just the

wild cherry or gean, brought to its present perfection by long

cultivation. It seems to have been well known to the old Highlanders, as

the bards often in singing the praises of their sweethearts, compare the

colour of their cheeks to the cherry—“ Do ghruaidh mar an t-siris”

Chestnut.—Latin,

Fagus casfcmea—Gaelic, Geanm-chno.— This tree is said to be a native of

England, but not of Scotland. This, however, is doubtful, for if it is

not a native, it must have been introduced into this country very early,

from the immense size of some of the chestnut trees found growing in

many parts of the Highlands. One growing in the garden of Castle Leod,

in Ross-shire, in 1820, measured 15 feet in circumference; and mention

is made, in the New Statistical Account, of three chestnuts measured at

Castle Menzies in 1844, whose respective girths were 16, 18^, and 21

feet. The wood is very hard and durable, and that its value was known to

our ancestors is proved by the fact that it is found along with oak in

the roofs and woodwork of some of our oldest Highland castles and

mansion houses.

Elder.—Latin,

Sambucus wger—Gaelic, Droman ; Craobh an dromain. —This is a native of

the Highlands, and was used by the Highlanders in many ways. They used

its berries for dyeing a brown colour, and of course everybody who has

heard of the “ Laird of Cockpen ” knows that a wine is made of the

flowers—

“ Mistress Jean she was

inakin’ the elder flower wine, Says, ‘ What taks the Laird here at sic

an ill time ] ’ ”

The berries also were

fermented into a wine, which was usually drunk warm. The medicinal

virtues of the elder were well known to our ancestors, for indeed it was

one of their principal remedies for many diseases ; and as a proof that

they were correct in this, and also that its virtues were known in other

countries, I may mention that the great physician Boerhaave regarded the

elder with such reverence for its medicinal virtues, that he always took

off his hat when passing an elder tree!

Fir,

(Scotch).—Latin, Pinus sylvestris—Gaelic, Giutha?.— The. Scotch Eir is

the “ most Highland ” of all our trees, and there is no tree that looks

nobler than it does towering amongst our bens and glens. In our earliest

records we find mention of our great Caledonian fir forest, which

extended from Glenlyon and Rannoch, to Strathspey and Strathglass, and

from Glencoe eastward to the Braes of Mar. This great forest has mostly

disappeared ages ago, caused principally by being cut, or set fire to

wilfully, or accidentally, by the different clans, during their

continual wars, or by foreign invaders. A large portion of the ground

which once formed part of this great forest is now converted into peat

bogs, in which are found embedded huge trunks of fir, some of which

still show traces of fire, or lying close to their roots or stocks,

which are firmly fixed by the roots in the underlying firm soil. The

largest portions of the ancient Caledonian forest left are in Rannoch,

Perthshire; m Braemar, Aberdeenshire; in Badenoch, Strathspey, Glenmore,

Rothiemurchus, Glenmoriston, and Strathglass, in Inverness-shire; near

Loch Maree, in Ross-shire; and at Cogeach, Strathnaver, and Dirry-Monach,

in Sutherland. The wood of this tree is very valuable, being easily

wrought, resinous, and very durable, a proof of which is mentioned by

Smith, in his “View of the Agriculture of Argyle.” He says:—“The roof of

Kilchum Castle, Argyleshire, was made of natural fir, and when taken

down, after having stood over 300 years, was found as fresh and full of

sap as newly imported Memel.” Besides using.it for roofs, the old

Highlanders also used this wood for floors, and for making chests, beds,

tables, and endless other domestic purposes. The resinous roots dug out

of the earth, not only supplied the best of fuel, but was used for

light, being split up into small splinters, which from the quantity of

rosin contained in them burnt with the brightness of gas. They were

burnt either on a flat stone or an iron brander placed near the fire,

under the large open chimneys in old Highland cottages ; and it was the

nightly duty either of the old grandfather or of the young herd boy, to

sit by the light and replenish it by fresh splinters as they burned

down, whilst the other members of the family attended to their domestic

duties, or sat and listened to the songs or traditions of by-gone days.

Lightfoot mentions that Pennant and himself observed the fishermen of

Lochbroom, in Eoss-shire, make ropes of the inner bark of the fir. He

also mentions another curious fact about the fir. He says :—“ The

farina, or yellow powder, of the male flowers, is sometimes in spring

carried away by the winds, in such quantities where the trees abound, as

to alarm the ignorant with the notion of its raining brimstone.” The fir

is very often mentioned by Ossian, and no doubt in his day many of the

large tracts, which are now barren peat mosses, were covered with

luxuriant pine forests. To explain how this great change came about I

may give the following extract from an able work, “ A Description and

History of Vegetable Substances used in the Arts and Domestic Economy.”

In the article on the Scotch fir, it says, page 26 :—“ One of the most

singular changes to which any country can be subjected, is that which

arises from the formation of extensive masses of peat-earth. They are

common in most of the colder parts of the world, and are known in

Scotland by the name of peat mosses. These accumulations of a peculiar

vegetable matter are a sort of natural chronicle of the countries in

which they are found. In the northern parts of Britain they point out

that the soil and climate were once far superior to what the country

now, in those situations, enjoys. The era of the first commencement of

these bogs is not known; but as in many of them, both in Ireland and

Scotland, are found the horns and skulls of animals of which no living

specimens now exist in the country, and have not been since the

commencement of recorded history, their history must be referred to very

remote periods. Notwithstanding this, the formation of a peat bog under

favourable circumstances does not appear to be a very lengthened

process, for George, Earl of Cromarty, mentions (Philosophical

Transactions, No. 330) that near Loch Brasn (Loch Broom), on the west of

Ross-shire, a considerable portion of ground had, between the years of

1651 and 1699, been changed from a forest of barked and leafless pines

to a peat moss or bog, in which the people were cutting turf for fuel.

The process, according to the Earl’s description, which has been

verified by the observations of others, is this :—The pines, after

having stood for some time deprived of their bark and bleaching in the

rains, which in that country are both heavy and frequent, are gradually

rotted near their roots, and fall. After they have been soaked by the

rains, they are soon covered by various species of f ungi. When these

begin to decay the ram washes the adhesive matter into which they are

reduced between the tree and the ground, and a dam is thus formed, which

collects and retains the water. Whenever this takes place, the surface

of the stagnant pool, or moist earth, becomes covered with mosses, and

these mosses further retain the water. It is a property of those species

of moss which grow most readily in cold or moist districts, to keep

decomposing at the roots while they continue to grow vigorously at the

tops. Cold and humidity, as has been said, are the circumstances in

which the mosses that rot and consolidate into peat are formed ; and

when the mosses begin to grow they have the power of augmenting those

causes of their production. The mossy surface, from its spongy nature,

and from the moisture with which it is covered, is one of the very worst

conductors of heat; and thus, even in the warmest summers, the surface

of moss is always comparatively cold. Beside the spongy part of the

moss, which retains its fibrous texture for many years, there is a

portion of it, especially of the small fungi aud lichens with which it

is mixed, that is every year reduced to the consistency of a very tough

and retentive mould. That subsides, closes up the openings of the spongy

roots of the moss, and renders the whole water tight. The retention of

the water is further favourable to the growth of the moss, both in

itself and by means of the additional cold which it produces in the

summer.” A very good story is told in Strathardle of a boy’s opinion of

a group of noble firs, when he saw them for the first time. His father

was many years keeper to the Duke of Athole, at Falar Lodge, which is

many miles away from any other habitation, and surrounded by huge

mountains, and at which not a tree is to be seen, though it was once the

very centre of the great Caledonian forest. The boy had been born and

brought up in that secluded place, and had never been from home, till

one day when he was well on in his teens he was allowed to accompany his

father to Strathardle. Having never seen a tree of any description, no

doubt the stunted birch and alder trees he saw when going down Glen-fernate

astonished him not a little, but when they reached Strath-loch, and

coming round the corner of the hill the group of fine firs behind the

farm houses there burst on the wondering youth’s view, within a few

hundred yards of him. He stood still with astonishment, wondering what

those huge stems with the tuft of green on the top could be, till at

last a happy idea struck him, and turning to his father, he exclaimed—“

Ubh, ubh, nach e am blaths gu iosal an seo, a ni am muth, seallaibh cho

mor ’sa dh’ f has an c&l.”—“ Ubh, ubh, does not the warmth down here

make a wonderful difference; see how big the kale has grown.” The poor

boy had never seen anything resembling those trees except the curly kale

or German greens in his father’s garden, and so came to the conclusion

that owing to the warmth of the valley the kale had grown to the size of

the fir trees.

Fir, Silver.—Latin,

Pinus Picea—Gaelic, Giuthas Geal.—This tree is a native of Germany, and

was introduced into England in 1603; and into Scotland in 1682, where it

was first planted at Inveraray Castle. One specimen of this tree

measured 15 feet in circumference at Castle Menzies, in 1844.

Fir, Spruce.—Latin,

Pinus Abies—Gaelic, Giuthas Lochlanach. —The spruce is a native of

Norway, but was introduced in 1548. It thrives to perfection in the

moist boggy parts of the Highlands, where immense trees of it are found

in many part of the country, many of them over 100 feet high.

Gean, or Wild Cherry.—Latin,

Cerasus Sylvestris—Gaelic, Geanais.—This is one of our native wild fruit

trees, where it thrives very well in the low straths, many trees of it

being 15 to 18 feet in circumference. The wood is very hard and

beautifully veined, and was much used for making articles of furniture.

Light-foot says that the fruit of the Gean, by fermentation, makes a

very agreeable wine, and by distillation, bruised together with the

stones, a strong spirit.

Hazel.—Latin,

Corylus Avellana—Gaelic, Calltuinn.—This native tree is very common in

most parts of the Highlands yet, though, within the memory of the

present generation it has disappeared from many a glen, where it once

grew in thickets. This is caused to some extent by the increase of sheep

and rabbits in the Highlands, especially the latter, who in time of snow

peel the bark off as high as they can reach, killing it of course very

soon. From the great quantity of hazel trees and nuts dug up from great

depths in peat bogs, it is evident that the hazel was very common all

over the country before the destruction of the great Caledonian forest.

It was always a favourite wood for making walking sticks, and was also

used for making baskets and hoops for barrels. Our ancestors had many

curious old superstitions regarding the hazel, and always considered it

a very unlucky tree, though they were fond enough of the nuts. Of the

nuts they made bread sometimes, which they considered excellent for

keeping away hunger on long and fatiguing journeys. They had also many

superstitions regarding the nuts, such as burning them on Hallowe’en

night to see if certain couples would get married ; and they counted

nothing so lucky as to got two nuts naturally joined together, which

they called “ Cnb-chbmhlaich,” and which they considered a certain charm

against all witchcraft.

Horse-chestnut.—Latin,

^Eesculus hippocastanum—Gaelic, ’Gheanm-chno fhiadhaich.—This tree is a

native of Asia, and was introduced into England in 1629, but not into

Scotland till 1709. Very large trees of it are quite common in the

Highlands now. The wood is worthless, but its handsome foliage and

sweet-smelling flowers render it very useful for ornamental purposes.

Juniper.—Latin,

Juniperis communis—Gaelic, Aiteann.—Next to the broom and the whin, the

juniper is the most common of all our native shrubs, and it has the

advantage over those of producing berries. Those berries, which have the

peculiarity of taking two years to ripen, once formed no small part of

the foreign commerce of the Gael, as we read that shiploads of juniper

berries used to be annually sent from the port of Inverness to Holland,

where they were used for making the famous Geneva or gin. That trade in

the juniper berries continued long, and might have done so still if the

modern art of the chemist had not discovered a cheaper, but, as is

generally the case, an inferior substitute for the juniper berries in

the distillation of Geneva, this will be seen by the following extract

from an old work:—“The true Geneva or gin is a malt spirit distilled a

second time with the addition of juniper berries. Originally the berries

were added to the malt in the grinding, so that the spirit thus obtained

was flavoured with the berries from the first, and exceeded all that

could be made by any other method. But now they leave out the berries

entirely, and give their spirits a flavour by distilling them with a

proper quantity of oil of turpentine, which, though it nearly resembles

the flavour of juniper berries, has none of their valuable virtues.” The

old Highlanders had very great faith in juniper berries as a medicine

for almost every disease known amongst them, and also as a cure for the

bite of any serpent or venomous beast. In cases of the pestilence,

fever, or any infectious disease, fires of juniper bushes were always

lighted in or near their houses, as they believed that the smoke and

smell of burning juniper purified the air and carried off all infection.

The juniper is the badge of the Athole Highlanders, and also of the

Gunns, Rosses, and M‘Leods.

Laburnum. — Latin,

Gytisus Alpinus — Gaelic, Bealaidh Sasunach.—This tree is a native of

Switzerland, and was introduced in 1596. Some of the largest trees of it

in Britain are in Athole, by the roadside between Blair-Athole and

Dunkeld. The old Highlanders used this wood for making bagpipes, for

which use it is very suitable, being very hard, fine grained, and

capable of taking a very fine polish. Many very old bagpipes are made of

this wood. x

Larch.—Latin,

Pinus Larix—Gaelic, Laireag.—Though not a native of the Highlands, the

larch is now one of our commonest trees, and it thrives as well here as

any of our native trees, as both the soil and the climate are admirably

suited to it. Linnaeus says that its botanical name “Larix” comes from

the Celtic word “Lar,” fat; producing abundance of resin, of course the

Gaelic name comes from the same. In the Statistical Account of the

parish of Dunkeld we read :—“Within the pleasure-grounds to the north

east of the cathedral, are the two noted larches, the first that were

introduced into Britain. They were brought from the Tyrol, by Menzies of

Culdares, in 1738, and were at first treated as greenhouse plants. They

were planted only one day later than the larches in the Monzie gardens,

near Crieff. The two Dunkeld larches are still (1844) in perfect vigour,

and far from maturity. The height of the highest is nearly 90 feet, with

girth in proportion.” Again, in the account of the parish of Monzie we

have :— “ In the garden of Monzie are five larches remarkable for their

age, growth, and symmetry. They are coeval with the celebrated larches

of Dunkeld, having been brought along with them from the same place, and

are now superior to them in beauty and size. The tallest measures 102

feet in perpendicular height; another is 22 feet in circumference, and

at a distance of 2 J feet from the ground 16 feet, and throws out

branches to the extraordinary distance of 48 and 55 feet from the trunk.

The late Duke of Athole, it would appear, evinced a more than ordinary

interest in the progress of these five trees, sending his gardener

annually thither to observe their growth. When this functionary returned

and made his wonted report, that the larches of Monzie were leaving

those of Dunkeld behind in the race, his Grace would jocularly allege,

that his servant had permitted General Campbell’s good clieer to impair

his powers of observation.” The larch is now very commonly planted in

the Highlands, and there are many extensive plantations of it which have

already attained a great size and value, especially in the district of

Athole, where, about the beginning of the present century, Duke John

planted some millions of it on the hills north of Dunkeld and Logierait.

Lime.—Latin, Tia

communes—Gaelic, Teile.—This beautiful tree is a native of Asia, and was

introduced into Scotland in 1664, where it was first planted at Taymouth

Castle, where there are now trees of it nearly 20 feet in circumference.

The wood, which though very soft, is close-grained and very white, was

much used by the old Highlanders for carved work. They also believed the

sweet-smelling flowers of this tree to be the best cure for palpitation

of the heart.

Maple.—Latin, Acer

campestre—Gaelic, Malpais.—This tree is a native of the southern

Highlands of Perthshire and Argylc. It very much resembles the plane,

but does not grow to such a size. The Highlanders made a wine of the sap

of this tree as they did of the birch.

Oak.—Latin,

Quercus robar—Gaelic, Darach.—This monarch of the forest is certainly a

native of the Highlands, though some writers, of the class who grudge to

see anything good either in the Highlands or in the Highlanders, try to

maintain that it was not anciently found north of Perthshire. This,

however, is clearly settled by the great quantity of huge oak trees

found embedded at great depths below the surface in peat mosses all over

the Highlands and Islands. All our earliest bards and writers also

mention the oak, and Ossian, who is believed to have flourished in the

third century, sings of hoary oak trees dying of old age in his day :—

“Samhach ’us m6r a blia

’ll triath

Mar dharaig’s i liath air Lubar,

A cliaill a dlu-gheug 0 shean

Le dealan glan nan speur;

Tha ’h-aomadh thar sruth 0 shliabh,

A coinneach mar chiabh a fuaim.”

“Silent and great was the

prince,

Like an oak tree hoary, on Lubar,

Stripped of its thick and aged boughs

By the keen lightning of the skies;

It bends across the stream from the hill;

Its moss sounds in the wind like hair.”

There are many huge oak

trees in different parts of the Highlands, which -are certainly several

hundred years old, such as at Castle Monzies, where there are oaks about

20 feet in circumference. Those trees must be very old, as it is proved

that the oak on an average grows only to about from 14 to 20 inches in

diameter in 80 years. The wood of the oak, being hard, strong, and

durable, was used by the Highlanders for almost every purpose

possible—from building their birlinns and roofing their castles, down to

making a cudgel for the herdsman or shepherd, who believed the old

superstition that his flock would not thrive unless his staff was of

oak. And after the Highlanders had laid aside their claymores, many an

old clan feud was kept np, and many a quarrel between the men of

different glens or clans was settled, by the end of a “ cuilair math

daraich.” The bark was of course much used for tanning leather, and also

for dyeing a brown colour, or, by adding copperas, a black colour. The

veneration which the Druids had for the oak is too well known to need

mentioning her 3; and it seems also to have been the custom in early

times to bury their great heroes under aged oak trees, for the bard

Ullin, who was somewhat prior to Ossian, says in “Dan an Deirg,” singing

of Comhal, Ossian’s grandfather—

“Tha leaba fo chos nan

clach

Am fasgadh an daraig aosda.”

“His bed is below' the

stones

Under the shade of the aged oak.”

The Highlanders used a

decoction of oak bark for stopping vomiting, and they also believed that

a decoction of the bark and acorns was the best possible antidote for

all kinds of poison or the bite of serpents. They also believed that it

was the only tree that a wedge of itself was the best to split it, which

gave rise to the old Gaelic proverb — “ Geinn dheth fein a sgoilteas an

darach ”—“ A wedge made of the self-same oak cleaves it.” The Gaelic

bard, Donnach idh Ban, refers to this belief in one of his beautiful

songs— “’S chnala mi mar shcan-fhacal Mu’n darach. gur fiodh^corr e, ’S

-gur g<$inn’ dheth fhein ’ga theannachadh A spealtadh e ’na ordaibh.”

Pine

(Weymouth).—Latin, Pinus Strobus—Gaelic, Giuthas Samnach.—This beautiful

tree was first introduced from England to Dunkeld, where the first trees

of it were planted in 1725.

Plane.—Latin, Acer

Psendo-plantanus—Gaelic, Pleintri, or Plinntrinn.—The first of those

Gaelic names, which sounds so very like the English, is that given by

Alex. M‘Donald (Mac Mhaighstir Alastaii^ in his Gaelic list of trees

already referred to. The second is that givfen by Lightfoot, as the

Gaelic name in use for this tree when he travelled in the Highlands in

1772. The plane is a native of the Highlands where it grows to an

immense size, as may be seen by the following extract from the New

Statistical Account of the dimensions of plane trees growing at Castle

Menzies, parish of "Weem—“solid contents of a plane, 1132^ feet; extreme

height, 77£ ; girth at ground, 23 ; at four feet, 16. Of a second plane,

girth at four feet from ground, 18£ feet; and of a third at four feet,

20 J feet.” The wood of this tree, which is white and soft, was much

used by the Highlanders for turning; and Liglitfoot mentions that they

made a very agreeable wine of the sap of the plane, as they did of the

birch and maple.

Raspberry.—Latin,

Rubus Idceus—Gaelic, Subhag, or Soidhcag. —The wild raspberry is one of

our native wild fiuits, and grows very commonly all over the Highlands,

where it also grows very well in a cultivated state in gardens. The

distilled juice of this fruit was once very much used by the old

Highlander in cases of fever, as it is very cooling. Lightfoot says that

the juice of this fruit was used in the Isle of Skye, when ho was there,

as an agreeable acid lor making punch instead of lemons.

Rowan, or Mountain Ash.—Latin,

Pyrus Auciiparia—Gaelic, Caorunn.—This beautiful and hardy tree is a

native of the Highlands, where the wood of it was once much used by

wheelwrights and coopers; but the great use the Highlanders made of the

rowan tree, since the days of the Druids, was for their superstitious

charms against witchcraft. I may give Lightfoot’s account of what the

Highlanders did with the rowan in 1772—“The rowan-berries have an

astringent quality, but in no hurtful degree. In the island of Jura they

use the juice of them as an acid for punch ; and the Highlanders often

eat them when thoroughly ripe, and in some places distil a very good

spirit from them. It is piobable that this tree was in high favour with

the Druids, for it may to this day be observed to grow, more frequently

than any other tree, in the neighbourhood of those Druidical circles of

stones so often seen in North Britain; and the superstitious still

continue to retain a great veneration for it, which was undoubtedly

handed down to them from early antiquity. They believe that any small

part of this tree, carried about with them, will prove a sovereign charm

against all the dire effects of enchantment or witchcraft. Their cattle

also, as well as themselves, are supposed to be preserved by it from

evil, for the dairymaid will not forget to drive them to the shealings

or summer pastures ^ ith a rod of this tree, which she carefully lays up

over the door of the sheal bothy, and drives them home again with the

same. In Strathspey they make, for the same purpose, on the first day of

May, a hoop of rowan wood, and in the morning and evening cause all the

sheep and lambs to pass through it.”

Willow. —Latin,

Salix — Gaelic, Seileach. — Lightfoot mentions sixteen, and Linnaeus

twenty varieties of the willow, natives of the Highlands, and many more

have been discovered since their day. The willow was a very valuable

tree indeed for the old Highlanders, and they converted it into almost

endless purposes. The wood, which is soft and pliable, they used in many

ways, and the young twigs, of course, for basket work, and even ropes.

Tlio bark was used for tanning leather, and the bark of most of the

varieties was also used to dye a black colour, while that of the white

willow gave a dye of a cinnamon colour. The following extract from “

Walker’s Hebrides ” describes the uses made of the willow in the Isles

:—“ The willows in the Highlands even supply the place of ropes. A

traveller there has rode during the day with a bridle made of them, and

been at anchor in a vessel at night, whose tackle and cable were made of

twisted willows, and these, indeed, not of the best kind for the purpose

; yet, in both cases, they were formed with a great deal of art and

industry, considering the materials. In the islands of Colonsay, Coll,

and Tyree, the people tan the hides of their black cattle with the bark

of the grey willow, and the barks of all the willows are capable of

dyeing black. The foliage of the willow is a most accept able food for

cattle, and is accordingly browsed on with avidity both by black cattle

and horses, especially in autumn. In the Hebrides, where there is so

great a scarcity of everything of the tree kind, there is not a twig,

even of the meanest willow, but what is turned by the inhabitants to

some useful purpose.”

Yew.—Latin, Taxm

Baccata—Gaelic, Iuthar.—This valuable tree is a native of the Highlands,

where the remains of some very old woods of it are to be found, as at

Glenure, in Lord, which of Course takes its name from the yew. There are

also single trees of it of immense size, and of unknown antiquity in the

Highlands, such as the famous old yew in the churchyard of Fortingall,

in Perthshire, described by Pennant, as he saw it in 1772. He gives the

circumference of it as 56½ feet, and it was then wasted away to the

outside shell. Some writers calculate that this tree must have taken

4000 years to grow that size, it is impossible now to tell its age Avith

any certainty. But when we consider its immense size, and the slow

growing nature of the yew, it is certainly one of the oldest vegetable

relics in the world. "When writing out this paper I wrote to the

minister of Fortingall to enquire wliat state the old yew was is in now,

and was glad to hear from that gentleman that part of it is still fresli,

and sprouting out anew, and likely to live a long time yet. We read of

another very large yew tree, which grew on a cliff by the sea side in

the island of Bemera, near the Sound of Mull, which when cut, loaded a

six-oared boat, and afforded timber enough when cut up, to form a very

fine staircase in the house of Lochnell. The wood of the yew is very

hard, elastic, and beautifully veined, and was much prized by the old

Highlanders for many purposes, but the great use to which they put it

was to make bows. So highly was the yew esteemed for this purpose that

it was reckoned a consecrated tree, and was planted in every churchyard

so as to afford a ready supply of bows at all times. And in fact, so

commonly were the bows made of yew, that we find in Ossian and in the

early bards .the buw always alluded to as “the yew,” or “my yew,” as in

“ Dan an Deirg,” we have,

“Mar shaighead o ghlacaibh

an iugliair,

Bha chasan a’ siubhal nam barra-thonn.”

And also in Diarmaid,

when that hero heard the sound of liis comrades hunting on Beinn

Ghuilbeinn he could remain quiet no longer, but exclaimed—

“A chraosnach dhearg ca

bheil thu

’S ca bheil m’ iughar’s mo dhorlach ? ”

Smith, in his “Sean

Dana,” in a note to “Dan an Deirg,” says :— Everybody knows the bow to

have been made of yew. Among the Highlanders of later times, that which

grew in the wood of Easra-gan, in Lorn, was esteemed the best. The

feathers most in vogue for the arrows were furnished by the eagles of

Loch Treig; the wax for the string by Baile-na-gailbhinn; and the

arrow-heads by the smiths of the race of Mac Pheidearain. This piece of

instruction, like all the other knowledge of the Highlanders, was

couched in verse—

“Bogha dh’ iughar

Easragain,

Is ite firein Loch-a-Tr&ig ;

Coir bliuidhe Bhaile-iia-gailbhirm,

’S ceaun o ’n cheard Mac Pheidearain.”

That the Highlanders in

the early days of Ossian used the yew for other uses than making bows is

proved by the passage in Fingal, describing Cuchullin’s war chariot—

“’Dh’ iutliar faileasach

an crann,

Suidhear ann air cnamhan caoin.”

“Of shining yew is its

pole ;

Of well-smoothed bone the seat.”

And that our ancestors,

in the third century, overshaded their graves with yew tree3, as we do

still, is proved by the passage in Fingal, where, after Crimor and

Cairbar fought for the white bull, when Crimor fell, and Brasolis,

Cairbar’s sister, being in love with him, on hearing of his death rushed

to the hill and died beside him, and yew trees shaded their graves—

“ Bhuail cridhe ’bu tla ri

’taobh,

Dh’ fhalbh a snuagh ’us bhris i tro’ ’n fhraoch,

Fhuair e marbh; ’us dh’ eug i’s an t-sliabh ;

’N so fein, a Chuchullin, tha’ n uir,

’S caoin iuthar ’tha ’fas o’n uaigh.”

“Throbbed a tender heart

against her side,

Her colour went; and through the heath she rushed;

She found him dead ; she died upon the hill.

In this same spot, Cuchullin, is their dust,

And fresh the yew-tree grows upon their grave.”

Arssmart

(Spotted).—Latin, Polygonum persiearia—Gaelic, Am Boinne-fola.—This is a

very common plant in the glens and low grounds of the Highlands. It is

easily known by the red spot on the ceutre of every leaf, about which

the Highlanders have a curious old superstition, viz. :—That this plant

grew at the foot of our Saviour’s cross, and that a drop of blood fell

on each leaf, the stain of which it bears ever since. A decoction of it

was used with alum to dye a bright yellow colour.

Bear-berry.—Latin,

Arbulus uva-ursi—Gaelic, Braoilcagan-nan-con.—The berries of this plant

are not eaten, but the old Highlanders used the plant for tanning

leather, and its leaves were used as a cure for the stone or gravel. It

is the badge of the Col-quliouns.

Bilberry or Blaeberry.

— Latin, Vactinium uligmosum — Gaelic, Lus-nan-dearcay, or Dearcag

Munaidh.—I need give no description of this well-known plant, but may

mention that its berries were used in olden times for dyeing a violet or

purple colour. Of this plant Lightfoot says :—“ The berries, when ripe,

are of a bluish black colour, but a singular variety, with white

berries, was discovered by His Grace the Duke of Athole, growing in the

woods midway between his two seats of Blair Athole and Dunkeld. [I may

add that this is now known to be a distinct species— the Vac-cinninn

myrtillus fructu-albo of botanists.] The berries have jan astringent

quality. In Arran and the Western Isles they are given in cases of

diarrhoea and dysentery with good effect. The Highlanders frequently eat

them in milk, which is a cooling agreeable food, and sometimes they make

them into tarts and jellies, which they mix with whisky, to give it a

relish to strangers.” The blaeberry is the badge of the Buchanans.

Bird’s-foot Trefoil.—Latin,

Lotus corniculatus—Gaelic, Bar-a'-mhilsein.—This beautiful bright yellow

flower grows all over the Highlands. It is very much relished by sheep

and cattle as food, and was used by our ancestors for dyeing yellow.

Colt’s-foot

(Common).—Latin, Tussilago farfara—Gaelic, An gallan gainmhich;

’Chluas-Liath. — This plant, with its broad greyish leaves, grows very

common in the Highlands, by the side of streams, and in boggy places. A

decoction of it was used for bad coughs or sore breasts.

Crotal, or Lichen

(Purple Dyers).—Latin, Lichen empha-lodes—Gaelic, Crotal.—This small

plant, which grows all over stones and old dykes in the Highlands, is

still very much used by Highlanders for dyeing a reddish^ brown colour.

It was formerly much more used, particularly for dyeing yarn for making

hose, and so much did the Highlanders believe in the virtues of the

crotal that, when they were to start on a long journey, they sprinkled

some of the crotal, reduced to a powder, on the soles of their hose, as

it saved their feet from getting inflamed with the heat when travelling

far.

Elecampane.—Latin,

Inula helenium—Gaelic; Ailleann.—This is one of the largest of our

herbaceous plants, as it grows to the height of several feet. It gives a

very bright blue colour, and it was much used for such by the

Highlanders, who added some whortle berries to it to improve the colour.

Heather. — Latin,

Erica cinerea — Gaelic, Fraoch. — The heather, the badge of the Clan

Donald, needs no description, but I may give Lightfoot’s account of what

the Highlander made of it in his day:—“The heather is applied to many

economical uses by the Highlanders. They frequently cover their houses

with it instead of thatch, or else twist it into ropes and bind down the

thatch with them in a kind of lattice work; in most of the Western Isles

they dye their yam of a yellow colour, by boiling it in water with the

green tops and flowers of this plant. In Rum, Skye, and the Long Island,

they frequently tan their leather with a strong decoction of it.

Formerly the young tops of it are said to have been used alone to brew a

kind of ale, and even now, I was informed (1772), that the inhabitants

of Isla and Jura still continue to brew a very potable liquor by mixing

two-thirds of the tops with one-third of malt. This is not the only

refreshment that the heather affords. The hardy Highlanders frequently

make their beds with it, laying the roots downwards and the tops

upwards, which, though not quite so soft and luxurious as beds of down,

are altogether as refreshing to those who sleep on them, and perhaps

much more healthy. ”

Honeysuckle

(Dwarf).—Latin, Comm succica—Gaelic, Lus-a’-chraois.—This elegant little

plant grows very common in Athole, and, I believe, iii many parts of the

Northern Highlands, especially Lochbroom. It has a white flower,

followed by red berries, which have a sweet taste. The old Highlanders

believed that if those berries were eaten they gave an extraordinary

appetite, from which it took its Gaelic name, which I find in an old

work translated “Plant of Gluttony.”

Ladies’ Mantle.—Latin,

Alchemilla vulgaris—Gaelic, Copan-an-driuchd, or Cota-preasach nighean

an High.—This pretty little plant grows in dry pastures and on

hill-sides all over the country, and there arc endless superstitions

connected with it, and virtues ascribed to it by the Highlanders, which,

if the half only were true, would make it one of the most valuable

plants growing. Both its Gaelic names are very descriptive of the leaf

of the plant, the first —“ Cup of the dew,” refers to the cup-shaped

leaf in which the dew lies in large drops every morning; and the

second—“ The King’s daughter’s plaited petticoat,” refers to the

well-known likeness of the leaf, when turned upside down, to a plaited

petticoat, which might indeed be "a pattern for a king’s daughter.

Mother of Thyme.—Latin,

Thymus serpyllum—Gaelic, Lus Mac-Righ-Bhreatuinn. -—This sweet-scented

little plant was believed by tlie Highlanders to be a preventive or cure

for people troubled with disagreeable dreams or the nightmare, by using

an infusion of it like tea.

Mugwort.—Latin,

Artemisia vulgaris—Gaelic, An Liath-las.— Till very lately, or perhaps

yet, in some of the out-of-the-way glens, this plant was very much used

by the Highlanders as a pot herb, as also was the young shoots of the

nettle, just as they use kale or cabbage now.

Shepherd’s Purse.

— La'in, Thlaspi Bursa-pasloris—Gaelic, Sporan-buachaill.—This plant is

still very much used in the Highlands for applying to cuts or wounds to

stop the bleeding, and it was much more so in olden times, when such

were more common.

Sea Ware.—Latin,

Fucus Vesiculosus—Gaelic, Feamainn.— This plant is very much used si ill

in the maritime parts of the Highlands in many ways. It makes an

excellent manure for the land, and in some of the isles it forms part of

the winter fodder of cattle, and even deer in hard winters sometimes

feed on it, at the recess of the tide. Lightfoot says that in Jura, and

some of the other Isles, the inhabitants used to salt their cheeses by

covering them with the ashes of this plant, which abounds with salt. But

the great use of the sea ware was for making kelp, which used to be very

much made in the Isles, and in fact gave employment to the most of the

inhabitants there. The way in which it was made was :—The sea ware was

collected and dried, then a pit about six feet wide and three deep was

dug, and lined with stones, in which a small fire was lighted with

sticks, and the dried plant laid on by degrees and burnt, when it was

nearly reduced to ashes the workman stirs it with an iron rake till it

began to congeal, when it was left to cool, after which it was broken up

and sent to the market. The average price of kelp in the Isles was about

£3 10s. per ton, but of course when extra care was taken, and skill

shown in the preparation of it, it was worth more.

Silver Weed or Wild

Tansy.—Latin, Potent ilia Anserina— Gaelic, Bar-a'-bhrisgein. — Of

this plant Lightfoot says : — “ The roots taste like parsnips, and are

frequently eaten by the common people either boiled or roasted. In the

islands of Tyree and Coll they are much esteemed as answering the

purposes of bread in some measure, they having been known to have

supported the inhabitants for months together during scarcity of other

provisions. They put a yoke on their ploughs and often tear up their

pasture grounds with a view to eradicate the roots for their use, and as

they abound most in barren and impoverished soils, and in seasons that

succeed the worst for other crops, so they never fail to afford the most

seasonable relief to the inhabitants in times of the greatest scarcity.

A singular instance this of the bounty of Providence to those islands.”

Turmextil.—Latin,

Torment ilia Kreda—Gaelic, Bar-braonan-nan-con.—This little plant may be

said to grow almost everywhere in the Highlands, where it was once much

used for tanning leather, for which purpose it is far superior even to

oak bark. We read that in Coll the inhabitants turned over so much of

the pasture to procure the roots of this plant that they were forbidden

to use it at all by the laird.

St. John’s Wort. —

Latin, Hypericum Perforatum—Gaelic, Achlasan Challum-Chille.—The old

Highlanders ascribed many virtues to this well-known plant, and used it

in many ways. Boiled with alum in water it was used to dye yarn yellow,

and the flowers put in whisky gave it a dark purple tinge, almost like

port wine. Superstitious Highlanders always carried about a part of this

plant with them to protect them from the evil effects of witchcraft.

They also believed that it improved the quality and increased the

quantity of their cows’ milk, especially if the cows were under the evil

effects of witchcraft, by putting this plant into the pail with some

milk, and then milking afresh on it. Another Gaelic term for this herb

is an ealbhuidhe, and is thus alluded to in Miann d Bhaird Aosda:—

Biodh s6bhrach bhan a’s

aillidh snuadh

Mu’n cuairt dom’ thulaich’s uain’ fo dhriuchd,

’S an ue6inean beag’s mo lamh air cluain

’S an ealbhuidh’ aig mo chluais gu h-ur.

Violet

(Sweet).—Latin, Viola Oderata—Gaelic, Sail-chuaich. —This fragrant

little flower grows all over the Highlands, and it was much used by the

Highland ladies formerly, in the following way:—

“Sail-chuach’s bainne

ghabliar,

Suadh ri t’ aghaidh ;

’S clia’n eil mac High ar an domliain

Nach bi air do dheidh.”

Whortle-Berry.—Latin,

Vaccinium vitis-idcea—Gaelic, Lus-nam-braoileag.—This plant, known to

every Highlander, grows on the hills all over the Highlands. The berries

were much used by our ancestors as a fruit, and in cases of fever they

made a cooling drink of them to quench the thirst. This is the true

badge of the Clan Chattan.

Wood Pease.—Latin,

Orobus tuberosus—Gaelic, Cor., Cor-meille, or Peasar-nan-Luch.—The roots

of this plant were very much prized by the old Highlanders, as they are

yet by most Highland herds or schoolboys. They used to dig them up and

dry them and chew them like tobacco, and sometimes added them to their

liquor to give it a strong flavour. They also use it on long journeys,

as it keeps both hunger and thirst away for a long time ; and in times

of scarcity it has been used as a substitute for bread.

Yarrow, or Milfoil.—Latin,

Achillea millifolium—Gaelic, A’ chaithir-thalmhain.—This plant, so well

known to every old Highland housewife, was reckoned the best of all

known herbs for stopping the bleeding of cuts or wounds and for healing

them, and it is even yet made into an ointment in some out of the way

glens in summer, that it may be at hand in winter, when the plant cannot

be procured. They also believed that it was the best cure for a headache

to thrust a leaf of this plant up the nostrils till the nose bled.

With these remarks I will

conclude, hoping that other members of the Society may take the matter

up, and add to our knowledge of this interesting subject.

Due

to all the various spellings in this article I have included a pdf file

of the article

This is a scan of the original document

Just after this article was produced a short

book on the same subject was published by Cameron and you can download

it here. |