By Primrose M'Connell, F.H.A.S., Ongar Park Hall,

Ongar, Essex.

Of recent years dairy farming has come greatly to the

front, and everything pertaining to a cow is of much importance to a

large section of the farming community. Dairymen are popularly supposed

by their arable brethren to be, in many cases, making their fortunes;

but, as the amount of these fortunes depends very much on the cost of

feeding and economical management of the stock, the lessening of the

outlay is always to be aimed at quite as much as the increasing of the

income, and very often offers greater opportunities for improvement; and

so a few notes on the subject may not be without interest.

These matters have been so often discussed at dairy

conferences and elsewhere, however, and there has been so much written

about them, that it will be well-nigh impossible to present anything

fresh; so, therefore, it is only proposed in this paper to give the

principal points connected with the working and feeding of a dairy of

cows, with some few comments thereon.

It will suit our purpose to divide dairy stock into

two kinds—(a) those kept for the supply of milk during summer

only, which milk is afterwards manufactured into cheese or butter;

(b) and those kept for an equal supply all the year

round, especially for town consumption. It is manifest that, at some

periods of the year at least, the style of feeding and management must

be different for the two kinds.

Summer Milking Cows.—As the oldest and most

natural way is to have cows yielding milk during summer only, we will

first consider it. Under ordinary circumstances, the animals are timed

to drop their calves in the early spring—the end of February, March, and

beginning of April. It is intended that they should all calve as nearly

as possible at the same period, so that there may be a sufficient

quantity of milk to work with, but as it is not possible to have all

served with the bull at the same time, and as some may not hold to the

first service, they drop in irregularly during a couple of months or

more. Under such circumstances, it is usual to put them dry in November

after being in milk for about eight to nine months. A cow, of course,

will yield milk for nine or ten months, or even longer, but where all

are gradually going dry at one time, the quantity of milk eventually

becomes too little to be worth the trouble of manipulating, and

therefore they are not milked for much over the eight months. Some

farmers, however, find it suitable to commence sending milk into town on

the approach of winter, and in such cases the animals are encouraged to

yield as long as possible. The lengthy period of three to four months'

rest allows them to recuperate, and they milk all the better for it

during the succeeding season. In fact, it is a matter of common

experience that, if an animal is drained too long, both her own

constitution and that of her growing foetus are injured: the calf will

be pining and weak, and the mother will not milk so well the next

season. An examination of the spongy mass of the udder shows that

microscopically it is made up of a very large number of little hollow

bags or sacs (alveoli), each lined with a coating of cells. It is

the function of these cells to manufacture the different ingredients of

the milk (butter-fat, cheesy matter, &c.) out of the blood, and when the

animal is not in milk, the open central space of each alveolus is

gradually filled up with loose cells similar to those which line the

walls of the cavity: this is one of the recuperative acts which are

brought about when a cow is not in work, and which takes time to bring

about. When lactation again commences at calving, these loose cells are

first of all cleared out, and give the peculiar character to the first

milk yielded, and which we call "colostrum" or "beistings." As this has

a purgative effect, it should be always given to a newly-born calf, as

nature intended, so that the internal machinery of the youngster may be

put right at the start. A cow should thus he allowed at least six weeks

to two months of a rest. Usually the bull is not put to them till the

end of June or beginning of July, so that they may come round at the

proper time again next spring, and one will serve some fifty cows during

the time allowed, though we have seen sixty allotted.

Summer Shelter.—The principal food of a cow in

summer is of course grass—if good grass so much the better—but there are

several matters connected with the general management which will first

be noticed.

The troubles which afflict our cattle most in summer

are heat, flies, and sometimes a scarcity of water. It may sound rather

paradoxical to say that cows require shelter quite as much in summer as

in winter,—but it is a fact nevertheless,—and any one who will endeavour

to supply them with shade will be well repaid for his trouble. Clumps of

trees, tall hedges, and even sheds, are all good investments in this

line; and though neatly trimmed fences look well on a farm, yet they

would be better liked by the cows if left a trifle "tousy." The torment

which cows suffer from "clegs" (Tabanus bovinus), warble-flies,

and others, is so great during bright sunshine that something ought

always to be done to relieve them. We have known a drop of twenty pounds

of curd—equivalent to as many gallons of milk— in a dairy of 60 cows in

one day from this cause alone. In some parts of the country, and

especially in the south, it is the custom to put them indoors for two or

three hours during the hottest time of the day, giving them some green

forage to eat.

Water.—In addition to shade, it is also

absolutely necessary that they should have plenty of good water. When we

remember that milk contains about 87½ per

cent. of water, and that a cow will use up, for milk-making purposes

alone, from three to four gallons daily in the flush of yielding, over

and above that which is required in the vital processes of digestion,

perspiration, &c, we can form some idea of the quantity required by each

animal, and therefore they must have an unlimited amount. The best way

to supply it is in the form of a running brook or river; and those

farmers, who have the command of such where the cattle can go into the

water and stand in the shade of trees during the hot part of the day,

can provide them with a bovine elysium. Recent sanitary science has

shown that the drinking water must be free from sewage contamination, or

other source of disease germs; but it is not necessary, nor even

desirable to have it "pure," in the ordinary sense of the term. If

cattle have access to spring water, and also to a running burn, they

will prefer the latter: the temperature is higher, the water is softer

usually, there is more air dissolved in it, so that it is not so flat or

insipid, while the probable presence of organic matter seems to render

it more palatable to them, and will do no harm so long as it is not the

carrier of disease germs. Even the stagnant water of ponds is not to be

despised, where running water is not to be had: the green scum on the

surface is nature's scavenger, taking up and utilising the decaying

matter which would form a fit breeding place for those malignant germs,

if such were introduced.

Salt.—It is a good plan to allow the cattle

access to rock salt on the pastures. Most farmers give this ingredient

in their winter feeds, but it is strange how few think it necessary to

give them an allowance during summer. Animals in a state of nature have

been known to travel many miles to lick saline rocks or earth; and this

is not very wonderful when we recollect that, in addition to its taste

being grateful to the palate, it is required to form one-half of the

solid matter of the blood, and has the power of enabling the digestive

organs to abstract more nutriment from the food. Cattle require about 4

oz. daily, part of which, of course, is supplied in the ash material of

the vegetables they live on. A safer plan than salting the food—for fear

of over or under doing it—is to allow them to help themselves, when they

will take just what they require, and no more.

Summer Food.—The principal food for a dairy cow

in summer is of course grass, which she collects herself; the higher the

quality of the pasture the better for the animal, and the quantity

allowed may vary from 1 to 3 acres per head. Old pasture will yield more

butter and cheese per gallon of milk, but young grass will give the

largest quantity where the number of gallons is of importance. In some

cases the grass may be so good that nothing more is requisite to make

the cows yield their utmost both in quantity and quality; but oftener it

will be found that the addition of some extraneous feeding material will

pay. This usually takes the form of either of the varieties of cotton

cake, and some 2 to 4 lbs. daily is the common allowance. With regard to

the use of this, however, a word of caution is necessary. Cotton cake,

in common with some other highly nitrogenous foods, is a very prolific

source of milk fever and " drop," if its use is not discontinued for a

long time before parturition; while if the milk is made into butter or

cheese, it often gives an objectionable flavour to these products. No

doubt much can be done to counteract this by intelligent and scientific

manipulation, but it is easier to do it by using some other food.

Oilcake is not so suitable as a food for cows, as it tends to lay on

fat, and oil does not produce milk at all. There is nothing to beat bean

meal either for quantity, quality, or flavour; and if it is mixed with

ground oats, so much the better, though the butter produced from this

latter will be rather pale in colour. This meal is best given as a ball

of dough—when given alone— made with warm water, and is relished

exceedingly by the cows. The comparative values of feeding stuffs,

however, will be touched upon again.

It is a good plan to have the pasture close to the

byre; if it is too far away the cows waste themselves in unnecessary

travelling, while there is a great inducement for the attendants to

drive them too quickly, and thus harass them. A cow with a full milk

vessel is quite unable to move fast, and it is a great mistake to hurry

her.

Forage.—In addition to the use of cake or meal,

however, it is a good plan, as mentioned above, to give an allowance of

green forage material, and for this purpose tares are generally used. It

is in the opportunity which arable farms give for the growth of large

acreages of forage crops, as an adjunct to the pasture, which has

rendered them so easily adapted to dairying where labour and markets

suited. Almost anything which produces a bulk of green food may be

grown—clover, rye, ryegrass, green oats, tares, &c, and though these

have not all the same value as food, yet some one or other of them will

suit any given set of circumstances. A mixture of food is always best,

however, and we have found from experience one similar to the following

is very suitable:—

Tares, 2 bushels.

Rye, 1 bushel.

Oats, 1 bushel.

This quantity sown per acre with a good dressing of

farm-yard manure will give good results. Where the climate is suitable,

the first break should be sown in autumn, and others at successive times

during the season, so as always to have a fresh shift coming forward. If

more is grown than the cattle can eat it may be cut and dried into hay,

and it will make a most suitable fodder for chopping up into chaff for

winter food.

Autumn Food.—Towards the latter part of autumn

the place of the tares will be taken by cabbage or soft turnips, and as

these are very liable to give an objectionable flavour to the milk and

its products, it will be found necessary to serve them to the cattle

immediately after the milking. By this means the essential oil,

or other aromatic compound which exists in the roots, seems to be

dissipated out of the system before the next milking comes round.

Concerning the use of roots, however, more will be said further on, but

it is here merely stated what is the usual practice.

We are now at the transition period between the

summer and the winter feeding and management, and this seems a

favourable point to introduce one or two subjects which require to be

noticed.

Milking.—It is a true saying, that the most

difficult part of the management of a dairy is the getting of the cows

properly milked. In Scotland it is nearly always women and girls who do

this, while in the south it is men and lads; but the getting of either

of them thoroughly trained is a difficult matter in many cases. It is no

exaggeration to say that the best animals, fed and cared for in the best

manner, may turn out poor yielders, or be utterly ruined, if milked by

one who cannot or will not take the milk from them properly. This is one

of the operations which is best learnt young, and the chief criterion of

ability is quickness. It is seldom that a quick milker is a bad

one, while quickness goes far to stimulate an inferior animal, and will

give a good one a chance of doing her best. The best stimulant to

quickness in the attendant is piecework, and it is a known fact that

where this work has been done at so much per week, some big records have

been made both as regards time and the yield of the cows. Ten cows is

the usual number allotted to each person, and it is quite possible, for

we have seen it regularly done, to milk these in one hour when in full

milk.

There seems to be an increasing dislike to this

species of work among the female servants on a farm, and it is difficult

to say what is to be done. It is strange, however, that among the many

ways of improving dairy matters in the shape of prizes to "Derby"

animals, milk records, experiments in feeding &c, nothing should have

been attempted in the way of improving the people who milk the cows, by

our show authorities or societies, although it is certain that there is

no department where there could be more good done, or where there is

more encouragement needed. It would not, of course, be easy to devise a

method of competition for milkmaids; but still there are no insuperable

difficulties in the way, while the good which would result ought to make

the matter worthy of consideration.

Milking should be done regularly, quietly, and

thoroughly, no scolding or beating, and the last drop to be extracted.

There is nothing which tends to lessen the yield of a cow so much as

ill-usage or bad milking; and where there are a number of attendants

they ought to take the cows in turn, so that the good milkers may help

to counteract the bad effects of the inferior milkers. Cows cannot

intentionally and deliberately "hold up" their milk; but if they are

frightened, the nervousness which is induced has a reflex action, and

the tissues of the milk vessels are tightened, so that the milk will not

flow so easily.

Everything ought to be done to keep the milk as

clean, as possible, so that the udders ought to be wisped over before

commencing if at all dirty; the attendants ought to wash their hands and

keep their nails pared. The last drop should be extracted, and for this

purpose some responsible person ought to go round after the regular

hands and "strip" them out. These "strippings" are the richest part of

the milk, and will amount to about 1 gallon to every twenty-five cows.

Milk Records.-—Of recent years we have come to

see the value of keeping an account of the milking capabilities of each

cow. "Where the average yield of each animal over a large herd is the

only thing desired, it is not necessary to keep very much of a record,

as the total yield divided by the number of animals will give this ; but

if any good is to result, we must know very much more than a general

average. Weighing the milk one day each week is the best way of arriving

at reliable data. When done once a week and the totals multiplied by 7,

we have the actual yield of each cow separately in pounds, and this sum

divided by 10 will give the imperial gallons near enough for all

practical purposes. Weighing the milk is a far superior method to

measuring, and a spring-balance, with the index adjusted to suit the

weight of the can, is the handiest kind of apparatus. There are several

good results which flow from a knowledge of the yield of each individual

cow, the most notable being the fact that some animals will turn out to

be unable to pay for their own living, and are kept at an actual and

direct loss. Another thing is that where the calves are reared to become

the milk cows of the future, as like produces like, the offspring of

good milkers will have the natural constitutional tendency to turn out

good milkers also (everything else being right), so that by this system

of selection the capabilities of the breed may be improved. Let no

farmer think that he knows his good milkers and his bad ones without

actual trial, or from the reports of the attendants only: if the real

annual yield of each were put down in black and white, there would be no

one more astonished than himself.

Very often it is found that a cow which was reckoned

good turns out second-rate, the reason being that she gave a large yield

for a short time, and then dried up quickly, so that the annual quantity

would not be great. On the other hand, many animals which never

impressed those working about them with regard to their milking powers

really turn up with a large total at the year's end, for the reason

that, though they never had much at a time, yet they kept it up for a

long period. A farmer can thus weed out the inferior animals, and as

much good will accrue to a herd as a whole from this as from any other

one thing.

Winter Management.—The change on to the winter

feed and management is done gradually. The cattle are kept indoors at

night as soon as the weather begins to get cold and stormy. As the time

goes on the period they are allowed outside becomes less and less, until

they are restricted to about an hour or so, except during very stormy

weather, when they should be kept indoors altogether. They should always

be allowed outside for a short time, if possible, however, as it gives

them exercise—they can scratch and rub themselves, and have an

opportunity of drinking if they so desire. As the time allowed out of

doors decreases, so of course does the food given indoors increase: at

first a few turnips, then an addition of fodder in the shape of straw or

hay, with meals or cake over and above. As the summer milking cows are

usually put dry on the approach of winter, they may at the same time be

put on to "maintenance diet," and indeed the quickest way to put them

dry is to restrict the feeding for a time. When a cow is not in milk,

and has only her own body and the growing foetus to keep up, she will do

with very much less food than when in milk; but she must be by no means

starved, though cakes and meals or other rich foods may, and in fact

ought, to be dispensed with. Where roots are used the order of these

is—first, soft turnips; next, swedes; and then mangolds in the spring

time, when these latter have thoroughly matured their juices.

As the springtime approaches they are allowed to go

out during an increasingly longer period each day—the time depending on

the weather—until they are out the whole day, and then afterwards at

night. The indoor feed is usually kept up until the season is pretty far

advanced, and until the grass outside is sufficient to take its place.

The most of them will have calved long before they are " out to the

grass," and such will be put on to a rich milk-producing diet

immediately they have recovered from the exhaustive effects of

parturition. A few days before calving, however, it is a commendable and

safe plan to give each a purgative—this "cleans them out," and acts as a

wonderful preventive of any bad results at the birth of the young.

Regarding their winter indoor management there are

several matters of general application which must be mentioned.

Ventilation.—First, there is the ventilation of

the byres or cowhouses, a matter very often neglected in practice to the

very great detriment of the health of the animals and of their owner's

pocket. A narrow, dark, ill-ventilated house is a great predisposing

cause of trouble among stock. The Government authorities have done good

service in insisting that all new milk dairies shall have a certain

amount of cubic space for each cow, and that there shall also be

abundance of light and air. It is not necessary to have the walls very

high—9 feet is quite sufficient; while the windows can be either in the

roof or walls according to circumstances. The ventilators, however,

should always be in the roof along the ridge: heated air always rises,

and can thus get out most readily at the top, carrying all the vitiated

products of respiration, perspiration, &c, along with it. There should

be an opening on each side and the ridge-plate or board carried down

between: this ensures that from whichever side the wind blows it will

enter and be deflected downwards, while the inside air comes up out the

other side. Thus there will be air without draughts, even when all the

doors and windows are shut up.

Temperature.—In connection with the ventilation,

there is the equally important point of the temperature. It has been

often stated that 65° F. is the proper temperature for a byre. The

writer has no hesitation in saying—as the result of his own trials—that

this is about 10° too high, and that 55° is quite sufficient and better

for the animals. The proper point to aim at is to have them warm and

comfortable, so that there may be no waste of food in keeping up the

heat of the body by respiration; and, on the other hand, not to have

them so hot that they perspire too much, and thus waste themselves in

another way. There is one other point, however, which militates quite as

much against the higher temperature as anything, and that is their

greater liability to take chills and "weeds" (catarrh of the udder) when

turned out daily, or when standing opposite a door which requires to be

kept open for some time. The lower temperature will, in fact, make them

more hardy; and from experience we can say that it is high enough to let

them yield their best.

Cleanliness.—Quite as important as regards health

and a good yield is cleanliness. Animals in a state of nature never do

get dirty, or at any rate are able to help themselves in the matter.

Cattle tied up to a stake, however, are quite helpless, and therefore

their masters must do something for them. A great deal depends on the

style and arrangement of the stalls, as if these are properly made, the

animal can stand and lie clean without any trouble. The style adopted in

the south-west of Scotland and other Scottish dairy districts is the

best: a low fire-clay manger in front, with a wide and deep gutter

behind, the bed being of such a length as just to allow the cow to stand

or lie with the head above the manger. With such an arrangement, the

droppings will always fall into the gutter, and the animals be dry and

clean. The style adopted in the south of having the mangers built up

high, with scarcely any gutter at all behind, is the way not to

do it.

The currycomb and dandy-brush should always be

liberally applied, and the cows will be grateful for it. It will also be

found a good plan to wash their backs, &c, with some sheep-dipping

composition occasionally, for the purpose of keeping down vermin.

The New-Milk Trade.—We now come to the

consideration of the management of herds devoted to the supply of new

milk which must be kept up all the year round. The summer treatment will

be pretty much like those where cheese or butter is made, with this

difference, that whereas in these latter the quality of the milk is of

more importance than the quantity, the quantity is the main factor for

the milk trade, and therefore the animals can be allowed a greater

amount of succulent forage. We do not mean to say that those in the

new-milk trade should lay themselves out to produce a large quantity of

poor milk, but as long as milk dealers and the public do not adequately

recognise the difference between milk containing 3 per cent. of

butter-fat and that containing 4 per cent., or over, so long will it

remain unprofitable for farmers to produce the higher quality. We have

known dealers who would not have milk with more than 10 per cent. of

cream, by the gauge; and others who desired 15 per cent. or over. A

producer would require to feed his cows accordingly, and the giving or

withholding of some cotton cake or other nitrogenous food will easily

regulate the cream percentage within certain limits. Milk which is

consumed within a day or so of its production will have little time to

develop bad flavours from the effects of particular kinds of food, as

would be the case with butter or cheese.

Management.—-The greatest difference in the

management, however, as compared with a cheese dairy, is in the timing

of the calving of the cows. It is manifest that it would be a great

mistake to have the cows all calving at one time in the spring; for, as

it is necessary to keep the supply of milk as nearly alike at all times

as possible, it is advisable to have them dropping their young at all

times the whole year round. In a dairy of fifty cows or so, it would

suit to have one coming into work every week on an average, but in

practice it will be found more suitable to have them coming in greater

numbers at one time than another. For instance, there must not be too

many during the natural flush of the milk at midsummer, and also because

they tend to go dry at the usual period in the beginning of winter. Thus

there are the two seasons of early spring and late autumn most suitable

for the greater proportion to arrive at parturition. Nevertheless, it

will not be found expedient to shut up the bull at any time, but he must

be kept constantly with the cows. No doubt the time of each cow's

calving will tend to shift forward a month or so each time— that is, if

a cow is served during her first heat, she will have her next calf in

less than twelve months; but, on the other hand, there is always a

proportion which will "come back" into a second period of heat, so that

the twelve months may be often exceeded. The life of a Cow is usually so

short that the extra drain on the system from excessive milking and

breeding will not matter much under ordinary circumstances. In this way

the number of cows in milk, or the quantity of milk yielded, can always

be kept near a fixed standard if so desired. Milk Yield.—Cows in

a dairy of this sort will usually yield more gallons during the twelve

months than those in work in a summer dairy only. The reason of this is,

of course, that while in the latter they are intentionally put dry at

the end of nine months or so, in the former they are encouraged to go on

yielding as long as possible—perhaps up till within a month of the next

calving, while a few may have their calves with less than twelve months

between. Of course, extra milking means extra food, as the animals must

have material out of which to manufacture the milk. It becomes a

question, however, how far it is profitable to force a cow by excessive

feeding beyond her natural capabilities; and it may almost be accepted

as a fact, that it is a mistake to carry it out to any great extent. The

system pursued at Rothampstead by Sir J. Lawes and Dr Gilbert is a very

sensible one, but unfortunately involves too much labour and trouble for

ordinary practice. At the above place a cow is fed according to the

quantity of milk she yields: she gets, say, 6 lbs. of cake daily when

yielding 30 lbs. of milk. This feed is kept up until she naturally

begins to fail, and then it is lowered in proportion, so that, say, an

animal has dropped to 20 lbs. daily, then her cake would also be dropped

to 4 lbs. It is a matter of proportion; for if a cow is sufficiently

well fed with 6 lbs. of cake while yielding 30 lbs. of milk, she must be

equally as well off with 4 lbs. to a 20 lbs. yield.

Feeding.—Unfortunately the winter yield of milk

has to a certain extent to be kept up against nature by a forcing feed.

Naturally the cows would give their full yield in the summer time when

the grass is at its best, and to make them do the same at mid-winter

means a large quantity of rich and costly food. The experience of the

writer is that—reducing everything to market prices—it will cost from

two to three times as much to keep a cow during the winter seven months

as during the summer five; in other words, if it costs £4 to £5 in

summer, it will cost £10 to £12 in winter, and even then the winter

yield will hardly be so good as that in summer. The winter milk trade is

therefore not a profitable one, the small extra price per gallon not

being anything like in proportion to the greater cost of production.

Foods.—The general style of feeding has already

been touched upon, and we may now consider the question of food more

particularly. The use of food in an animal is threefold— first, to be

consumed in the lungs to supply animal heat and " force "; secondly, to

supply material to make up for the tear and wear of the tissues, or for

the growth of the same; and, lastly, in a cow, to make milk. It is this

latter, of course, that we, as dairymen, are specially concerned with;

but the others are quite as important, and we may just note how the food

ingredients are allotted in the system. All food contains six "proximate

constituents"—water, albuminoids, fats, carbohydrates (starch, sugar,

&c), fibre, and ashes. Water is of use as a solvent and vehicle for the

others; albuminoids are the nitrogenous parts which specially go to form

flesh and muscle, and hence are called " flesh-formers"; fats or oils go

to be oxidised in the lungs for heat, and are therefore known as

"heat-producers"; the carbohydrates serve the same purpose as fat or

oil, only in a lesser degree,—1 of fat being equivalent to 2.3 of starch

for food purposes,—while the surplus of both is stored up as animal fat

in the tissues; fibre is the indigestible part which serves to give bulk

to the food, so as to suit the large stomachs of the cow; and the ash

goes principally to make bone, but is also found in other parts. All

these elements must be present and in proper quantity, because there are

special parts of the digestive track set apart for acting on each one.

It has been found that the nitrogenous portion should bear to the

non-nitrogenous a ratio of 1 to 5 or 6, and this is called the "albuminoid

ratio," or "nutritive ratio." The non-nitrogenous portion consists of

the fats, oils, starch, gum, sugar, &c, and the fatty part must be

brought to the same value as the starch by multiplying by 2.3. If any

one who has found that the rations he gives to his cows keeps them in

good health and in good milking condition, will take the trouble to work

out the proportions from the analyses and number of lbs. of each kind of

food (cake, meal, hay, &c), he will find the figures to come out very

nearly 1 to 5 or 6.

Relation of Food and Milk.—The effect of foods on

the milk is the main point to be noticed. Naturally we would expect that

the albuminoids, fats, &c, of the food would go to form the

corresponding bodies in the milk; but this is not the case. The caseine

as developed in the cells of the milk-glands seems to be the excreted

nitrogenous waste of the body, and, though no doubt eventually derived

from the nitrogenous matter of the food, depends more immediately on the

exercise which the cow gets. . This is most likely one of the reasons

why our Ayrshires are so suitable for cheese-making; they have been

developed in a district where they have had to tramp around a good deal

to get their bellies filled. Again, the butter fats of the milk are not

derived from the fats or starch of the food, but from the albuminoids.

In practice we never find such foods as rice, maize, or oilcake

satisfactory, starch and oil being the leading ingredients; while

nitrogenous foods, like beans or cotton cake, have an immediate effect

on the cream-yield and total solids. As a general rule, rich foods will

give rich milk. The question of the market cost of each, however, and

the readiness with which it can be obtained, is of great importance; and

it is easy to see that anything grown on the farm must be usually

cheaper than it can be bought. Of recent years the extreme cheapness of

wheat has caused many queries to be put in the farm papers relative to

its suitability for dairy cows. Mr John Speir, of Cambuslang, has shown,

in an article contributed to the North British Agriculturist,

that it is very suitable, both from theory and from his own practice.

Wheat in the shape of flour, or scones, or bread, is an excessively

starchy food, and would not suit a cow; but the grain ground up with the

bran and other coats is another matter, and comes out with our

albuminoid ratio of 1 to 5. Bran is generally given as a separate item,

but here we have it all without any expense or trouble. Beans have made

a name for themselves as a food for dairy cows, but prices and handiness

may make it more desirable to use something else. The writer uses a

mixture of beans, oats, and bran. Foods must not be given in too

concentrated a form, for the reason that the "stomachs" of the cow are

intended to deal with bulky material, not always of the most nutritious

description; while the power of ruminating implies a thorough

mastication and saturation with saliva, so as to assimilate all the

nutriment out of everything. There must therefore be always a fair share

of fodder— either straw or haw—to give them material for exercising this

ruminating power.

Effect of Cold.—The greatest drawback to a cow

yielding full milk in winter is the cold—a frosty night or day being

immediately followed by a decrease in the milk yield. For those animals

which are dry, of course, it does not matter so much ; but for those in

milk there should be an endeavour made to keep them as warm and

comfortable as possible without overdoing it. One of the best things for

promoting this end is the use of warmed food. It has been proved over

and over again as the result of direct experiment and of general

practice, that cold food retards the flow of milk, while if it is warmed

it promotes it. Such foods as fodder, cakes, &c,

are such bad "conductors" of heat that they never feel cold to

the touch in frosty weather, and therefore warming these—even if it

could be done—would do no good; but when we come to such things as water

itself, turnips, &c, where there is much moisture, something is required

to be done. In Scotland there is a common practice of giving

"boiling"—that is, warm mashes composed of chaff or chop mixed with

meals, and made into a sloppy mess with warm water. There is no practice

more commendable than this, and nothing more suitable for keeping up the

milk yield; besides it is the most convenient method of giving meals of

any kind, and of utilising "shorts," "tails," and any odds and ends of

fodder which can be passed through the chaffcutter. On the other hand,

there is nothing more detrimental to the quality and quantity of the

milk than the use of cold roots. Boots are always cold, but when they

are actually frozen they are ten times worse, and it is a wonder that

there is not more positive injury caused by them. It is certain that the

estimation they are held in as food substances is far above what they

really deserve. Boots generally have upwards of 90 per cent. of water in

their composition—that is to say, out of every 10 cart-loads there are 9

of water—which water could be more economically supplied by the pump or

spiggot. Further, it costs from £8 to £10 per acre to • grow them—that

is, about 8s. to 10s. per ton—and they are not worth to eat so much as

this at the comparative prices of other foods. It is argued that as they

are "green" food they have special nutritive or digestive value: to this

it may be answered that neither practice nor science has found that they

are any better or so good as warm mashes, while the latter are far and

away the cheapest. It is of course absolutely necessary to give cows

succulent sloppy food while in milk at this period of the year, but it

will be found when everything is taken into account that the cheapest

and best is that made with chop, meal, and warm water—"sappy," and not

"steamed" merely. The writer has elsewhere gone pretty fully into the

comparative values of roots, ensilage, and mash, as winter foods for

cows {Live Stock Journal Almanac, 1887), and does not wish to

repeat himself too much; while the system of farming to be followed when

roots are left out of the rotation is outside the scope of this essay,

though a cheaper and more efficient substitute will be found in tares or

other forage material grown for hay, to be afterwards cut up into chop.

It is usually considered that mangolds are better

food for milk cows than turnips, as they increase the yield: the result

of an experiment tried by the writer extending over a period of four

weeks is directly opposed to this. It was found that, weight for weight,

mangolds gave 6 per cent. less milk than turnips, and slightly less

cream: the Rothampstead experiments showed ensilage to be practically

scarcely any better than mangolds.

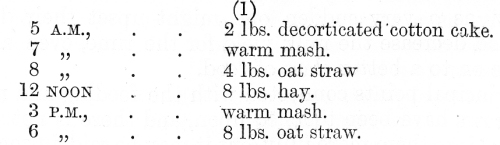

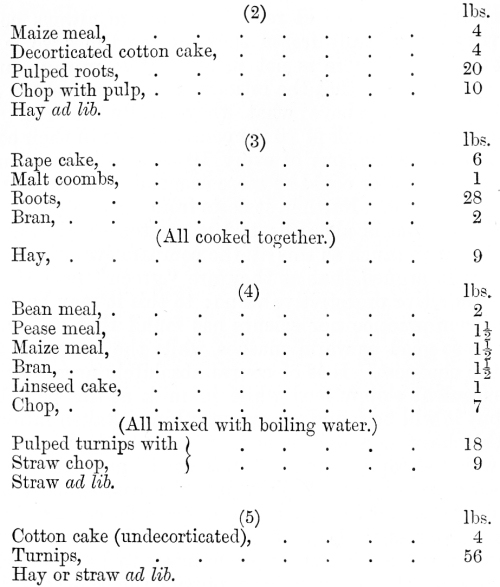

The following tables of rations are taken from some

in actual practice by different people, and may serve to illustrate the

winter food of a cow in milk:—

The warm mashes in the above consist each of about 5

lbs. chop, 2 lbs. of meal (bean and oat mixed), 2 lbs. of bran, 20 lbs.

Water—all together forming about a bucketful.

There is, of course, no

hard and fast rule about quantities and kinds. Different animals will

require different amounts, not only with respect to those of different

breeds, but also as between animals of the same breed, although this

paper has been written with special reference to Ayrshires. Further, the

price and accessibility of materials will have much to do with the

matter. A cow should have as much as she can eat, but no more; while a

good cow will respond more readily to generous rations than an inferior

animal. Regularity in feeding is a great matter, and it is usually easy

to carry it out in practice. When regular, the animals will soon know to

lie down and rest between the feeding times, placidly chew their cud,

and thus conduce directly to the formation of milk. Any change in the

food should be done gradually, as a very sudden one might upset their

digestive organs, and decrease the milk yield for the time, even

although it may be on to a better class of food.

The principal points connected with the feeding and

management of cows have been touched upon, and there is not time or

space to go into them more fully, but it may be said, in conclusion,

that the more close personal attention is given to them the better will

the money results be.